Systems Built On Heroics Are Brittle

What Hurricane Florence Taught Me About The Cost Of “Can-Do” Culture

Field note context

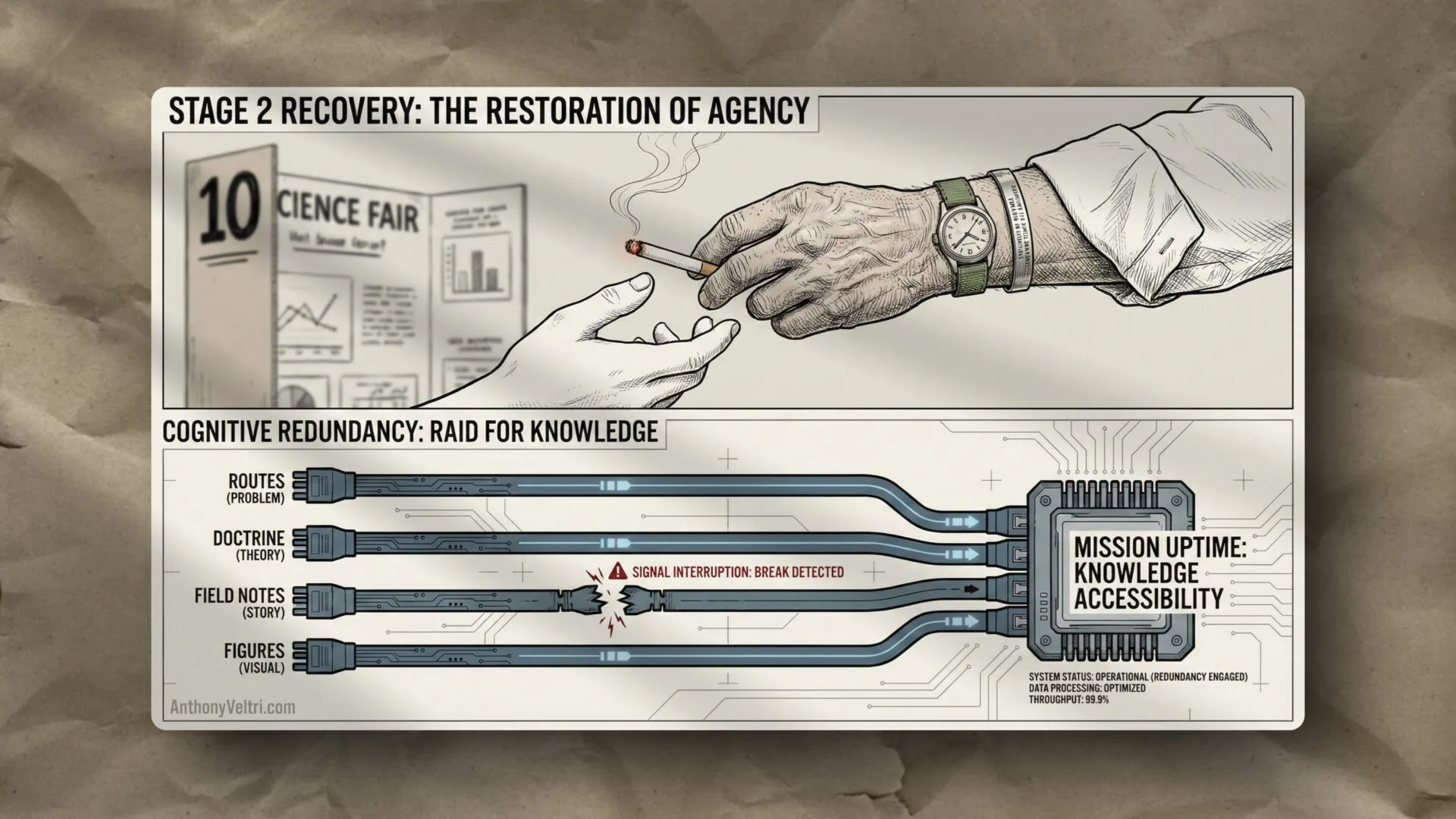

This story sits alongside two other pieces about how systems really behave under pressure, not how they look in a slide deck.

- In What the Katrina book was really for, I wrote about documenting a response in a way that protects the people who did the work instead of sanitizing them out of the record.

- In Guarding the room, I wrote about keeping a scientific discussion focused on what actually matters for funding decisions, not on technical side quests.

This one adds a third angle. It is about what happens when a system depends on heroics, what it cost me personally after Hurricane Florence, and how my own wiring and experience changes the way I think about evaluation and fairness in hiring.

Sometimes the moment you realize something is wrong shows up in the most ordinary place.

For me, it was a can of whipped cream.

I had just returned from ten days deployed to Hurricane Florence response in North Carolina. I was making coffee. One of my small indulgences is whipped cream on top. When I went to press the nozzle, it did not work.

Not like the can was empty. Like my hand was not strong enough.

Normally I could crush that nozzle with one hand without thinking. That morning it required two thumbs and effort. I thought maybe I was just tired from the deployment. I thought I could sleep it off.

I could not.

The deployment model

I worked for the U.S. Forest Service, but like many federal employees trained in the Incident Command System, I could deploy as a single resource to assist other agencies during disasters.

In September 2018, Hurricane Florence devastated the Carolinas. USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service needed help evaluating their food aid distribution systems.

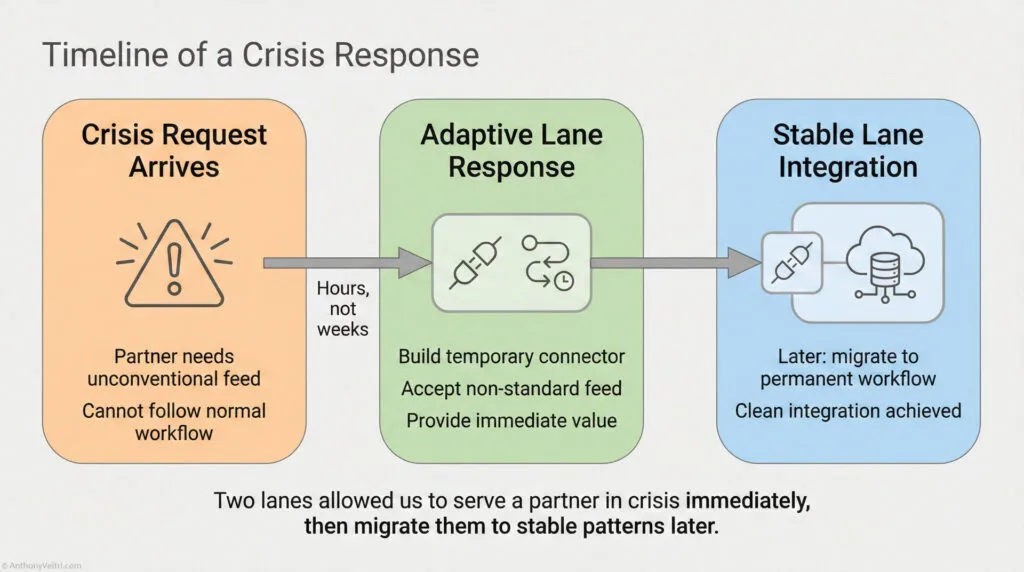

This is what I do: assess systems under pressure, collect evidence from field operations, and help shape improvements for future deployments. It is two lane architecture applied to disaster response. Keep current operations running while gathering intelligence to improve the next iteration.

I deployed from Oregon as a single resource. Once I reached North Carolina, I linked up with a small USDA team already on the ground. That is standard for incident response. You bring together people from different agencies who share common ICS training and can operate together under pressure.

For ten days, I worked 16 hour shifts in water flooded buildings and disrupted communities. My primary task was conducting video interviews with shelter workers, county officials, and local coordinators receiving federal food aid.

The goal was not to change anything mid crisis. You do not redesign systems while they are under load. The goal was to capture what was working, what was not, and why.

Those testimonials would help USDA refine their protocols for future disasters. It is the same principle I have used in other training environments. Run the course exactly as designed, then collect feedback after each session to improve the next iteration. Do not modify during execution. Learn systematically for next time.

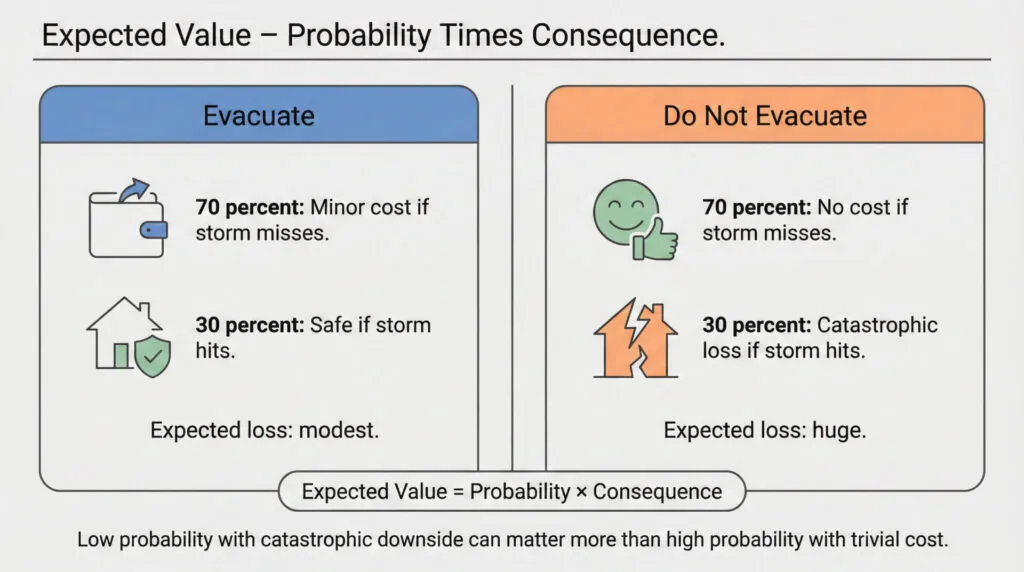

The safety briefing before deployment mentioned environmental hazards: flooded areas, damaged infrastructure, disrupted utilities. Mosquitoes were noted, but the briefing indicated that disease risk was low.

That assessment turned out to be wrong. I would not know that until later.

When things go wrong

A day or two before my scheduled return, I developed a sore throat and difficulty swallowing. By the time I landed back in Oregon, I could barely lift my equipment cases off the baggage carousel. These were cases I normally carried without effort, two at a time.

Something was wrong, but I did not yet understand what.

I went to an emergency room in Corvallis. The physician on duty knew me from the local trail running community. We had crossed paths at races over the years. He took one look at me and said I was not running the race scheduled for that weekend.

That was when I knew it was serious. This was someone who understood my baseline fitness, and he was telling me not to run.

Tests followed: blood work, lumbar puncture, MRI. My grip strength was measured at roughly 70 pounds. My pre illness baseline was about 130 pounds. That is not fatigue. That is profound weakness.

I was admitted to a regional medical center and treated with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) for suspected Guillain Barré syndrome: an autoimmune disorder where your body attacks your peripheral nerves, causing progressive weakness and sometimes paralysis.

The treatment worked. Over five days, I regained enough function to be discharged.

The question remained: What triggered this?

An infectious disease specialist in Corvallis took on the investigation. He noted that I had been exposed to numerous mosquitoes during the North Carolina deployment and ordered testing for mosquito borne illnesses.

The test for West Nile virus came back positive. I had antibodies indicating recent infection.

He reviewed my travel history carefully. I had not been anywhere else with West Nile exposure in the previous year. Not Oregon. Not any other states I had traveled to. The only location that fit was North Carolina during Hurricane Florence. The incubation period for West Nile virus ranges from 2 to 14 days, which matched my symptom timeline.

His medical opinion: the acute neurologic syndrome was caused by West Nile virus infection, most likely acquired during my deployment.

The institutional response

In February 2019, roughly four months after my hospitalization, I received a denial letter from the Department of Labor’s Office of Workers’ Compensation Programs.

Despite the infectious disease specialist’s documented conclusion linking my illness to the Hurricane Florence deployment, my claim was denied. The stated reasoning: medical evidence was insufficient to establish causation under the Federal Employees’ Compensation Act.

The letter cited early physician statements, made while doctors were still ruling out differential diagnoses, as evidence of uncertainty about the cause.

The specialist’s conclusion connecting West Nile infection to deployment exposure was either not in the file when the decision was made or was deemed insufficient to meet the legal standard for work related injury.

Medical treatment authorization was terminated. Hospital bills, which would eventually exceed $100,000, were now my responsibility.

At this point, the Forest Service stepped out of the picture. Federal workers’ compensation is administered entirely by the Department of Labor, not by the employing agency. Once DOL made its decision, the Forest Service had no authority, no seat at the table, and no ability to influence the outcome.

My supervisor could, and did, advocate for me by confirming the facts of my deployment when DOL asked whether the agency contested my claim. She stated that everything I had reported was accurate.

That was all the Forest Service was permitted to do.

From that point forward, this was between me and OWCP. The agency that had deployed me, praised the work I had done, and valued my contribution had no role in whether I would be covered for an injury sustained doing that work.

I hired a specialized federal workers’ compensation attorney. Regular personal injury lawyers do not handle federal cases. The Federal Employees’ Compensation Act has its own rules and procedures, and there are only a handful of law firms with expertise in this area. The attorney worked on contingency. He would only be paid if we won.

For the next eight months, I provided additional medical documentation, underwent more examinations, and participated in hearings within DOL’s appeals process. The case was remanded for a second opinion examination by a physician selected by OWCP.

In October 2019, my claim was accepted. The second opinion physician confirmed what the Corvallis infectious disease specialist had documented nine months earlier: West Nile virus infection, acute neurologic syndrome, causally related to environmental exposure during Hurricane Florence deployment.

The acceptance letter stated that “medical bills with respect to the accepted condition are now reimbursable by OWCP.”

Three months later, in January 2020, I received another letter from the Department of Labor: Notice of Proposed Termination.

OWCP proposed to end my medical benefits. The reasoning: the same second opinion physician who had confirmed my claim had also concluded that I was “fully recovered with no residuals and no impairment” from the West Nile infection.

Technically, that was true. I had no acute symptoms that required active medical treatment.

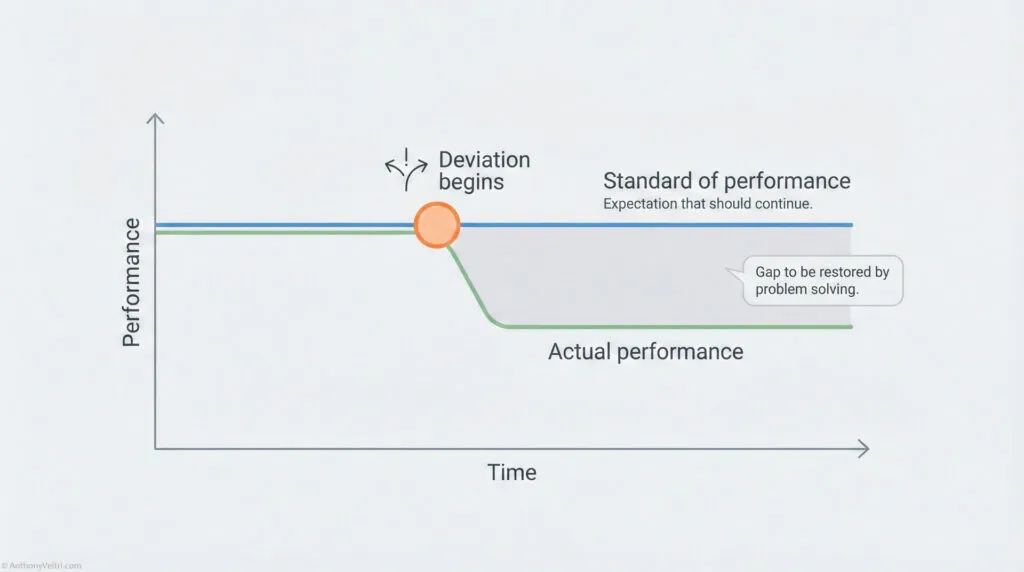

But “fully recovered” depends on what you measure against.

In September 2019, when the second opinion examination occurred, my grip strength was approximately 100 to 110 pounds. That was significantly better than the 70 pounds at my worst, but still 20 to 30 pounds below my pre illness baseline of 130 pounds.

I was functional. I could walk, work remotely, and perform daily activities. By OWCP’s standards, I was recovered.

I was not operating at the capacity I had before Hurricane Florence.

It would take until 2023, five years after the initial infection, before I found a specialist who helped me fully regain baseline strength and manage the persistent muscle spasms that had continued. The treatment protocol he developed was not complicated. It simply addressed things the earlier care had not prioritized.

The roughly $16,000 I paid out of pocket for medical expenses during the denial period was never reimbursed. Despite the claim being accepted, despite the letter stating expenses were “now reimbursable,” and despite submitting all documentation through my attorney.

Neither was my attorney, who had worked the case on contingency for over a year.

I am not telling you this for sympathy. I am telling you because this is what ‘the system will take care of you’ actually translated to in my ledger: real costs that never came back.

The doctrine lesson: why this pattern matters

If you lead teams, build systems, or deploy people into high pressure environments, here is what matters about this story:

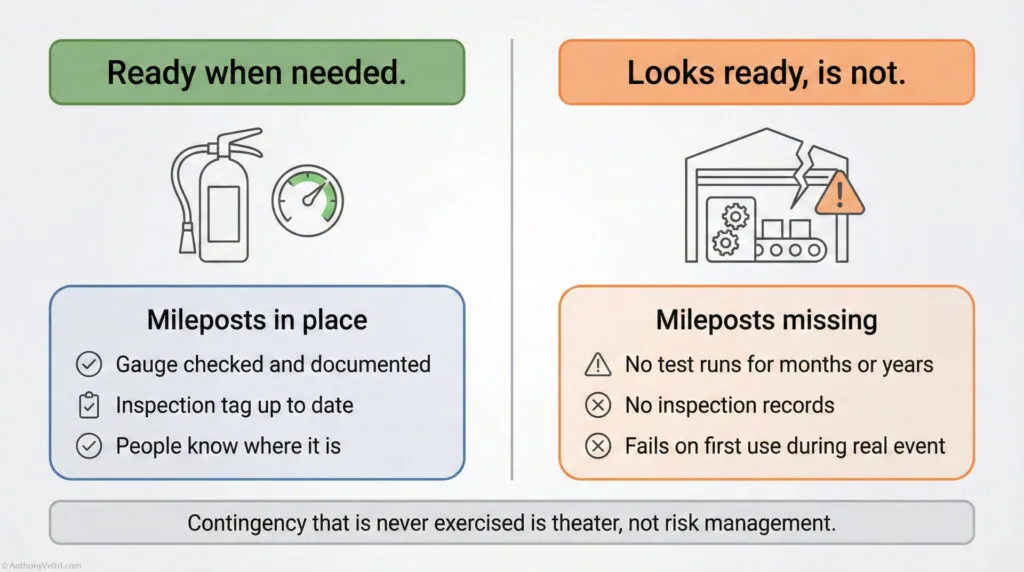

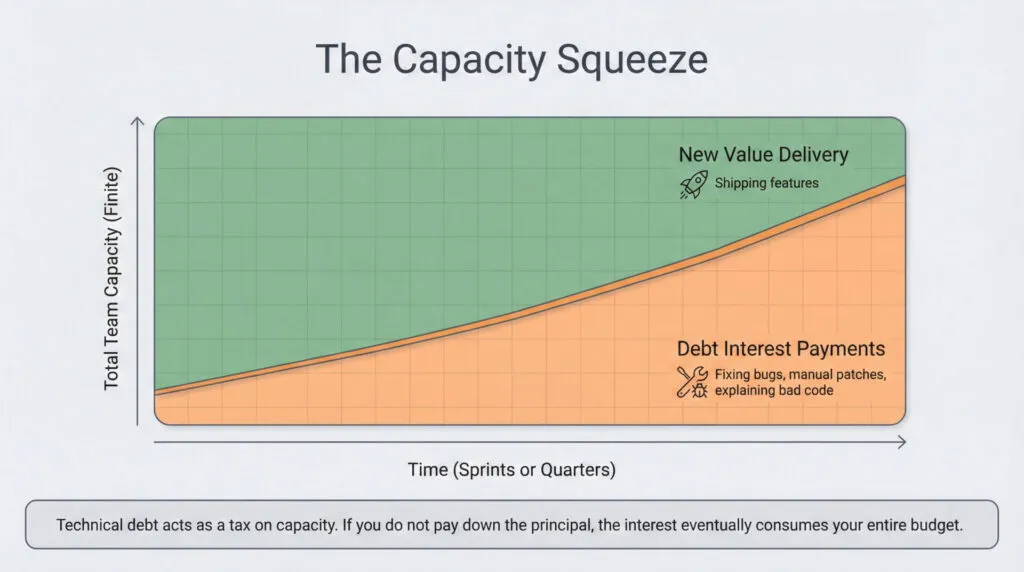

Systems built on heroics are fundamentally brittle.

Not because heroics do not work. They do, in the short term. But heroics cannot be sustained without eventually breaking either the people operating the system or the system itself.

Federal agencies, and many organizations that work under pressure, value what is often called “can-do spirit.” In the Forest Service, it is explicit cultural language. When disasters hit, you need people who show up and do whatever it takes to help.

That capability is real and necessary.

But “can-do spirit” without institutional capacity to sustain it is just heroics with better branding.

And systems built on heroics are brittle.

Here is what a capacity-based system would have looked like in this case:

- Accurate risk assessment. Environmental briefings that reflect actual field conditions, not optimistic projections. There were West Nile carrying mosquitoes in the operational area, despite the briefing indicating low disease risk.

- Team deployment. Sending two people instead of one, so there is redundancy if someone gets sick, injured, or needs support. Single resource deployments extract maximum value but provide no backup.

- Default acknowledgment. When someone gets sick during or immediately after deployment, the starting assumption should be work-related until proven otherwise, not the other way around.

- Streamlined support. If someone is injured doing work you asked them to do, you do not make them hire a specialized attorney and fight for eight months to prove a connection that medical experts have already documented.

- Long-term accountability. “Fully recovered” should mean restored to pre-injury baseline, not “functional enough to work at reduced capacity.”

- Financial follow through. If you accept a claim and state that expenses are “now reimbursable,” you actually reimburse them.

- Institutional authority. The deploying agency should have some role in supporting their people when things go wrong, not be cut out entirely once another bureaucracy takes jurisdiction.

None of this happened.

In hindsight: On my side of the ledger, I carried my own part of the heroics pattern too. I said yes to a single-resource deployment with 16 hour shifts because that was the cultural norm and I liked being the person who could take it. If I were advising a younger version of me, I would tell him to push harder on deployment structure and risk briefing before wheels up, not after something went wrong.

Not because anyone involved was malicious or incompetent. DOL was following its procedures. The attorneys were doing their jobs. The physicians were providing accurate medical opinions within the scope of their examinations.

The system was not designed to protect the people it deployed. It was designed to deploy people, extract value from their work, and return them to their regular jobs.

What happens if they get hurt doing that work becomes their problem to solve, with their own time, their own money, their own attorney, and their own fight against a separate bureaucratic system the deploying agency has no power to influence.

That is systems brittleness at the structural level. The organization that extracts value from your work has no responsibility or authority over the consequences when that work causes harm.

Heroics work until they do not. Then they break.

I deployed to Hurricane Florence. I did good work. USDA got valuable field intelligence on their food aid distribution systems. The video testimonials I collected helped refine protocols for future disaster response.

The work had value.

If your system depends on people like me saying yes to single resource deployments, working 16 hour days in hazardous conditions, and absorbing all the consequences when things go wrong, your system is built on heroics, not capacity.

When systems built on heroics break, they break the people who made them work. Then you lose the capability you were depending on.

Why evaluation context matters

There is a connection between what happened in North Carolina and how organizations evaluate people.

The Hurricane Florence deployment worked because I was operating in my element: collaborative problem-solving with stakeholders under real constraints. Video interviews with county officials. Working sessions with shelter coordinators. Iterative system assessment with USDA teams.

That is the work I am good at.

But getting hired for roles that require that work often depends on something else entirely: performing well in formal panel interviews.

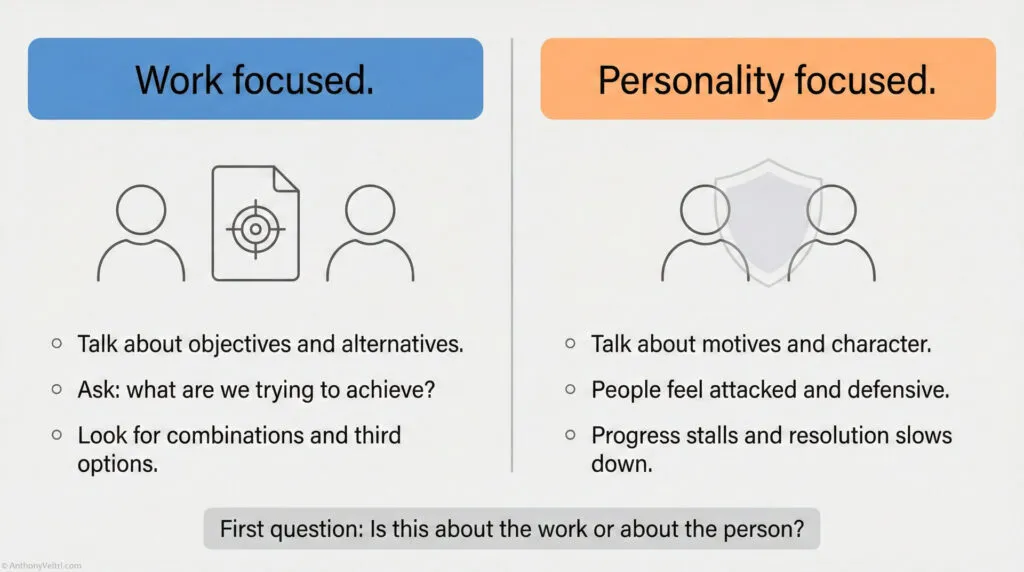

The irony is that the evaluation format tests for a different skillset than the job requires. Panel interviews reward one-way performance under observation. The actual work requires dialogue, iteration, and trust-building over time.

This creates a false negative problem: organizations filter out operators who excel at the actual work because they struggle in an evaluation format that doesn’t match how the work gets done.

I write about this pattern in detail in The Audition Trap: Why Panel Interviews Create False Negatives. The short version: if you are hiring for stakeholder work, test for stakeholder work. Don’t test for audition skills and hope they correlate.

Why my “not okay” helps other people be okay

One of the quiet advantages of knowing I am not perfectly put together is that I am not trying to pretend otherwise in front of stakeholders.

A lot of senior stakeholders show up to workshops and discovery sessions like they are walking into a deposition. Guarded. Defended. Every answer filtered through what the record might show.

I show up a little different. I am prepared, but I am not polished in a TV anchor way. I am comfortable showing that I am still thinking something through. I can say “I am not sure yet, let us work it out together” without feeling like I have failed.

That visible “not okay” makes other people more comfortable.

It gives them permission to be honest instead of defensive. They do not feel cross-examined. They feel like they are in a working session with someone who is on their side.

The fictional lawyer Perry Mason leaned into this. He was a little unkempt, a little clumsy, and witnesses would relax around him because he did not present as perfectly composed. In his case, that was a tactic.

In my case, it is not an act. It is just how my wiring and history present in the room. The effect is similar. People relax. They talk. They stop performing and start telling the truth about how their systems actually work.

That is where real stakeholder value comes from. Not from perfect lines in a slide deck, but from people lowering their guard enough to say, “Here is what is really happening.”

The irony is that the same traits that help me get to the truth with stakeholders are invisible, or even penalized, in high-stakes panel interviews.

Fair to who? Predictive of what?

Organizations use structured evaluation processes in the name of fairness. Same questions, same scoring, documented process.

But fairness to whom? Predictive of what?

If your evaluation format rewards:

- Quick thinking in one-way formats

- Polished monologue delivery

- Comfort being judged as a performer

Then you are selecting for people who excel at auditions, not necessarily people who excel at the work.

For roles that require:

- Collaborative problem-solving

- Stakeholder trust-building

- Iterative system design

The relevant skills look different. You want people who can tolerate ambiguity, draw honest information from guarded stakeholders, and adjust their approach based on real-time feedback.

Panel interviews barely test for these things. In some cases, they invert the signal. The person who looks slightly less polished in the audition may be exactly the person stakeholders will open up to in the field.

This is the same pattern as the deployment story. A system that can extract value from people’s capability once they are inside, but makes it unnecessarily hard to get in if they don’t perform well in an evaluation context that doesn’t match how the work actually gets done.

Build evaluation that tests for the work, not just the interview.

My “I am okay not being okay” stance does exactly that in real work. It drops people out of deposition mode. It signals that they do not have to perform for me. That is where the real data comes from.

None of that shows up in a scored panel interview. In some rooms, it reads as less polished. The exact trait that makes me effective with stakeholders in an operating environment can read as a weakness in a format that rewards stage performance.

So when we say panel interviews are “fair,” we should finish the sentence.

Fair to who?

Predictive of what?

If the job is actual stakeholder work, then fairness should include people whose working style makes them excellent in that environment, even if they are not the top performers in a one way, no monitor, stadium style audition.

Cross links to other doctrine

This principle connects to other patterns I write about:

- Federation over integration. Systems that respect autonomy and constraints of partners scale better than systems that force uniformity. Heroics are a form of forced integration. You demand that people adapt to system demands without the system adapting to protect them.

- Two lane architecture. Keep production running while you build improvements. Do not redesign during crisis. Also do not build systems where production depends on burning through people.

- Named stewards. Systems need identified owners who are accountable for outcomes. Heroics diffuse accountability. When everyone is responsible, no one owns the consequences.

- Resilience as emergent. Resilience emerges when systems are designed to survive degraded conditions. If your system only works when everyone operates at 100 percent, it is not resilient. It is fragile.

What this means for you

If you lead teams that operate under pressure

Whether disaster response, forward deployed capability, high tempo operations, or any environment where people work beyond normal conditions, ask yourself:

Am I building institutional capacity, or am I depending on heroics?

Capacity looks like:

- Redundant deployment and backup for key roles

- Accurate risk assessment that does not hide uncomfortable truths

- Default acknowledgment when work causes harm

- Streamlined support when things go wrong

- Long term accountability for people who bear the cost

Heroics look like:

- Single resource deployments with no safety net

- Optimistic risk projections that downplay real exposure

- Making people prove causation after they are hurt

- Expecting them to absorb financial and career consequences

- Considering them “recovered” when they are only functional enough to work

Heroics extract value until they break the people providing it. Then you lose the capability you were depending on.

If you are designing evaluation processes

Ask yourself:

Does our gatekeeping mechanism test for the work, or test for performance in our evaluation format?

Panel interviews select for people who think quickly under observation and deliver polished monologues. That is valuable when the job requires executive presentations or rapid fire decision making in front of large audiences.

If the job requires:

- Collaborative problem solving

- Stakeholder management through dialogue

- Building systems iteratively with partners

then panel interviews may be filtering out exactly the people you need.

Consider whether conversational interviews, work samples, trial projects, or evaluation over time would give you a better signal on actual capability.

If someone’s resume shows sustained high level work over decades but they struggle in your interview format, ask yourself:

Is the interview revealing a capability gap, or a format mismatch?

If you are someone who says yes to high stakes work

Recognize the difference between being supported by institutional capacity and being extracted from.

Capacity-based systems build infrastructure around you. Heroics-based systems expect you to be the infrastructure.

You can still say yes. Just know what you are agreeing to, and what the system will and will not do when things go wrong.

Where things stand now

In early 2025, my federal position was eliminated as part of nationwide workforce restructuring. Many positions were eliminated. It had nothing to do with Hurricane Florence or any medical issues.

My former Forest Service supervisor, who had advocated for me during the workers’ compensation fight, now works for a federal contractor. She hired me onto her team. I am grateful for her continued support. It is a reminder that relationships matter. She knows what I can actually do because she has seen me do it.

The persistent muscle spasms finally resolved in 2024, six years after the initial infection, with proper specialist treatment.

That is not what this story is about anymore.

This story is about why systems built on heroics are brittle, and why I design systems now that do not require them.

It is also about why I advocate for evaluation processes that test for actual work capability,

especially collaboration, dialogue, and problem solving over time,

rather than performance in artificial formats that select for a different performance profile than the job requires.

If you are building systems, build for capacity, not heroics.

If you are hiring people, test for the work, not just the interview.

If you are deploying teams, recognize that once people get hurt, they may be on their own navigating a separate bureaucratic system that you have no power to influence.

Build your systems knowing that.

Last Updated on December 11, 2025