I’m an Enterprise Architect focused on interoperability and governance in regulated, cross-boundary environments. I design the decision rights, interface ownership, and reference architectures that let sovereign or semi-autonomous teams deliver together without collapsing into forced integration. My background spans U.S. federal and multi-agency programs, including environments with degraded modes and strict security constraints. This work emerged from two decades of forward-deployed experience. Wildland fire academies to Hurricane Katrina, from federal geospatial systems to coalition-style mission networks.

My background looks like three different career on paper (it is actually one continuous pattern). I focus on seeing gaps in high-consequence environments, building practical systems to close them, and documenting what works. This site is a “Personal Practitioner Archive” designed to supplement, not replace, official organizational frameworks.

Here’s how I got here, and why I work the way I do now.

Education: Realizing I Was Missing The Ground

My formal training started in remote sensing and GIS. I was in a Natural Resources department working on wildland fire with satellite imagery. Landsat, early LiDAR, the kinds of tools that let you model fire behavior from orbit.

My major professor kept pushing the research deeper, which is how I walked out with two master’s degrees instead of one.

But somewhere in that work, a critical realization hit me: I was modeling fire behavior from space without really knowing what it felt like on the ground. I understood the spectral signatures and the spatial models, but I didn’t understand how incidents were actually run under pressure, how decisions got made when the fire was moving, or what the information picture looked like when it mattered most.

So I started fixing that gap. I sent myself to wildland fire academies. Not as a novelty trip, but as part of the research. Brookhaven, Colorado, Utah, back to Brookhaven multiple times. I learned fire behavior, Incident Command System structure, how aviation and ground operations coordinate, and how fragile the information flow can be when decisions are time-critical.

The pattern that would define my career started there: ground truth before design. Don’t architect from the rear. Understand how the work actually happens before you build systems to support it.

The Mobile Mapping Unit and Hurricane Katrina

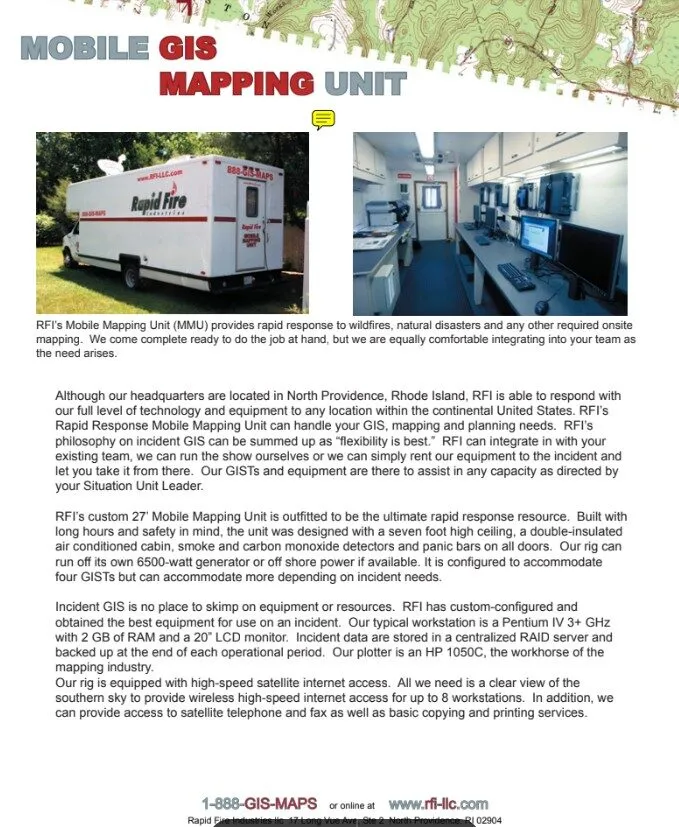

Somewhere between those fire academies and the lab work, an idea clicked: if you could bring a self-contained GIS and mapping capability directly to an incident, you could close a real operational gap.

So I built one.

In my final months of grad school, I bought a 26-foot box truck on eBay. A former New York State mobile testing center with high walls, insulation, and an Onan generator that could run the whole rig. I turned it into a mobile GIS lab with workstations, a large-format plotter for incident maps, and enough space for people to actually work inside it.

The fire season that followed didn’t produce the big wildland incidents I’d been targeting. Then Hurricane Katrina hit, and the mobile mapping unit suddenly had a very different role to play.

I deployed alongside the Rhode Island Urban Search and Rescue Task Force to the Gulf Coast. They didn’t have to bring me in. I wasn’t one of their long-time firefighters or medics. I was the guy with the truck and the maps. But they chose to fold me into their operations and treat that capability as part of the team.

The truck became a mapping and geoprocessing hub for a team that otherwise wouldn’t have had that capability. It was a physical anchor for electronics, radios, and computers in a chaotic, high-stress environment. I later wrote a book documenting the Rhode Island USAR story and the wider response efforts we intersected with. Not as a vanity project for me, but as narrative infrastructure for them. A way for the team to show families, officials, and future decision-makers what they’d actually done and why sending them so far from home was worth it.

Katrina taught me something I still carry: forward-deployed capability works when it plugs into existing teams who already know how to operate under pressure. You bring what’s missing. They bring trust, coordination, and the operational tempo you can’t replicate from a distance.

In a coalition, accuracy is important, but always secondary to alignment.

In the chaos of the Gulf Coast response, I learned that the “Best Map” is irrelevant if the team cannot agree on it. This briefing outlines the Doctrine of Alignment: Why we must negotiate the “Treaty of the Truth” before we can coordinate the response.

From GIS to RF: Following The Mission Requirements

Katrina also shoved me into a new domain: communications.

On paper, my world was maps and imagery. On the ground, it quickly became clear that GIS and RF are joined at the hip when you care about path loss, line of sight, and where you can actually put antennas to maintain connectivity in disrupted environments.

I was already a ham radio operator, comfortable with RF in the high-frequency world. After Katrina, I stretched into wireless networking, distributed antenna systems, continuous wave drive testing, and eventually WiMAX (yes, that long ago) backhaul for telephony over IP in disaster response contexts.

I got my OSHA tower climbing certification in Georgia because the RF work required it. I wasn’t building a resume. I was following mission requirements. If the work needed me to climb towers, model path loss with GIS terrain data, or validate signal strength in the field, I learned how to do it.

This became another through-line: skills aren’t collected for their own sake. They’re acquired because the mission demands them. Every certification, every new domain I moved into, came from seeing a gap and building the capability to close it.

The Federal Career: Building Institutional Capability

During twenty years of federal service (reaching the GS-14 level), my work focused on building institutional capability across geospatial systems and mission-critical communications.

Some of the systems I led or supported:

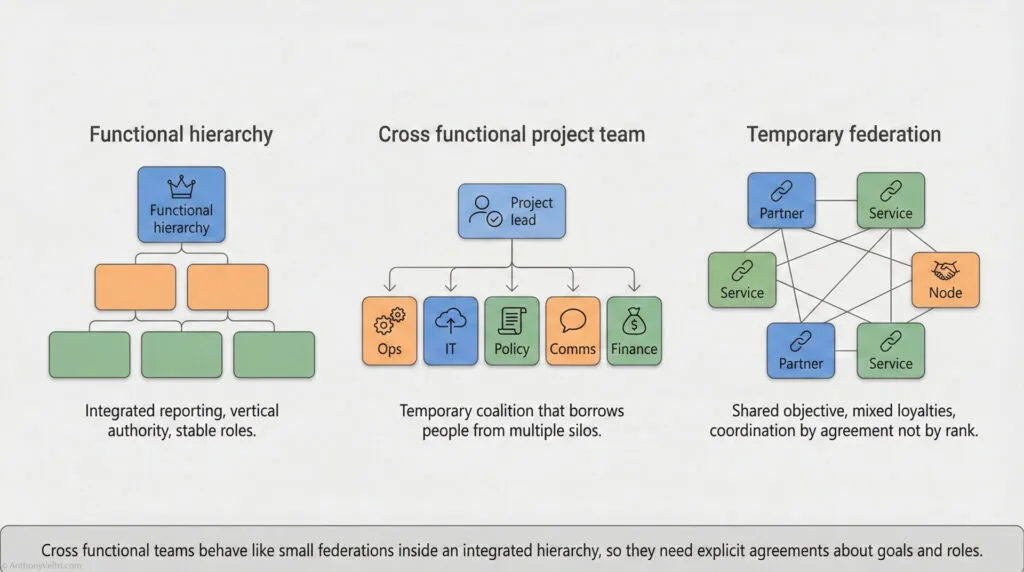

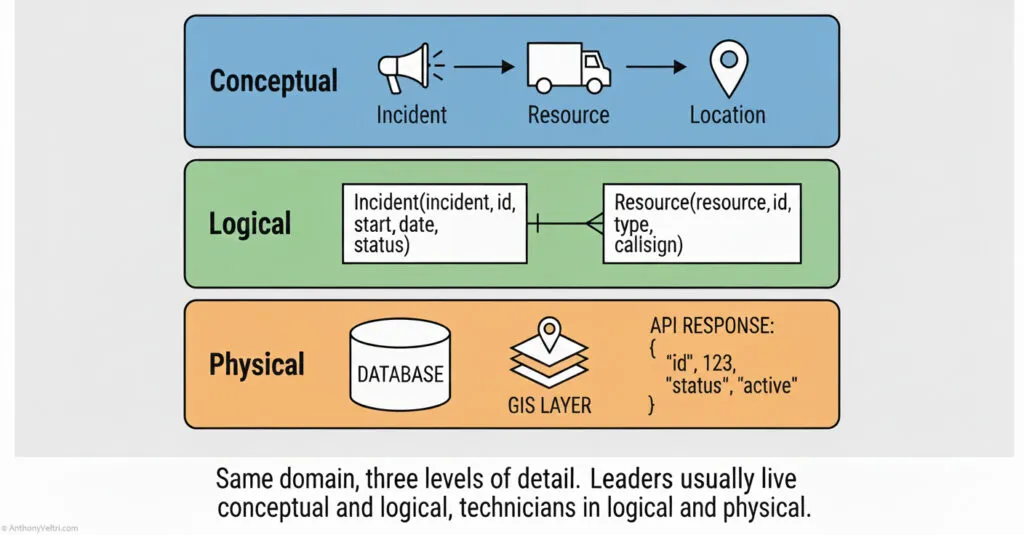

iCAV (Infrastructure Common Awareness Viewer). A federated geospatial architecture that let partners contribute data at their own maturity level without forcing everyone into one platform. This is where I learned that federation scales with diversity, while integration only works when you control every partner.

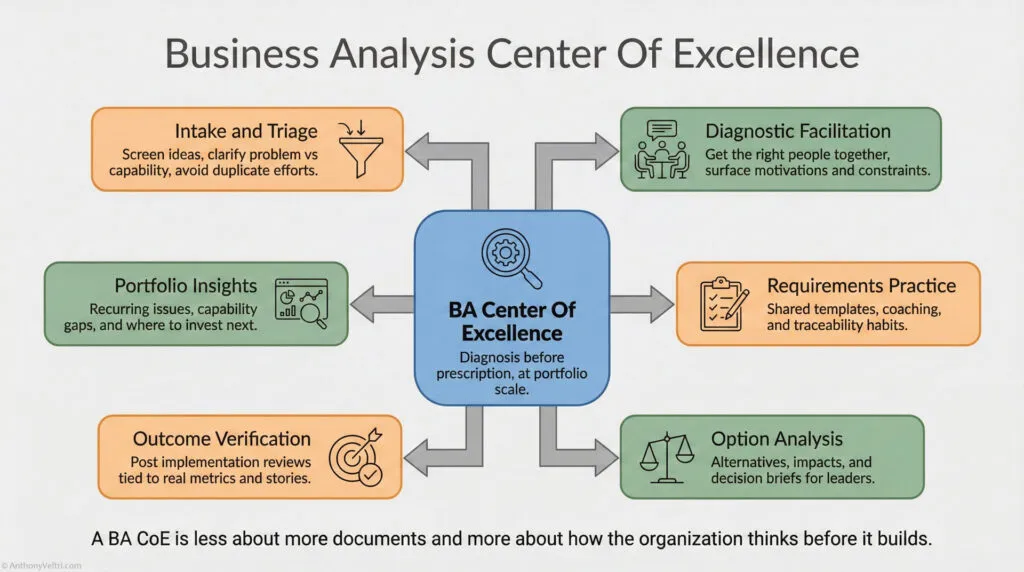

Business Analysis Center of Excellence. Building institutional capability for requirements analysis and stakeholder management across federal programs.

Government Video Guide and testimonial frameworks. Internal doctrine for how federal teams could capture evidence of their impact without turning into marketers. Video as accountability infrastructure, not promotional content.

The pattern stayed consistent: I wasn’t just operating systems. I was building the capability so others could operate them after I moved on. Documentation, training, frameworks that could be handed off. Systems that didn’t require me to stay in place for them to survive.

I also became a pilot during this period. Not for recreation, but because airborne collection work required understanding aviation constraints, airspace, and what’s actually feasible when you’re trying to coordinate ground and aerial operations.

Why Media Became Part of the Work

My media work didn’t start in a federal agency. It started in my grandfather’s basement.

He had served as an airman in World War II in the Pacific, first as a ball turret gunner on a B-24, later moved into technical work on aerial reconnaissance. When he came home, he built a small darkroom in the house he built.

As a kid (sixth or seventh grade) he taught me how to:

- Load and expose film

- Develop negatives in trays under a red light

- Use an enlarger to project an image onto photographic paper and bring it to life in the developer

That was my first lesson in what it means to take images seriously. Not as throwaway content, but as records and as craft.

He was also a talented mechanic after the war. He helped me build and maintain the mobile mapping unit. He took me to the volunteer examiners so I could get my FCC amateur radio license in junior high school.

That thread runs straight through the work I later did for the Forest Service, DHS, and private sector clients. The Government Video Guide, the testimonial frameworks, the media tradecraft I taught to Fire and Aviation Management. All of it came from understanding that images and stories are accountability infrastructure, not decoration.

When code breaks, relationships hold.

We spend millions trying to build the “Universal Connector” to automate trust, yet we often fail where the old world succeeded. This briefing deconstructs the “Swivel Chair Interface” (arguing that what looks like inefficiency is actually the only adapter flexible enough to handle a crisis). My grandfather didn’t rely on middleware; he relied on stewards. We must stop trying to replace the human API and start empowering it.

Hurricane Florence and the Cost of Heroics

In September 2018, I deployed as a single resource to support USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service response to Hurricane Florence in North Carolina. My role was evaluating food aid distribution systems and collecting video testimonials from shelter workers and county officials to help refine protocols for future disasters.

A day or two before my return flight, I developed a sore throat and difficulty swallowing. By the time I landed back in Oregon, I could barely lift my equipment cases off the baggage carousel.

I was hospitalized with Guillain-Barré syndrome. An autoimmune disorder where your body attacks your peripheral nerves. Testing showed I’d contracted West Nile virus during the deployment. My grip strength dropped from 130 pounds to 70 pounds. Treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin worked, but recovery took years.

I wasn’t fully recovered. It took until 2023 (five years after the infection) to regain my baseline strength with proper specialist care.

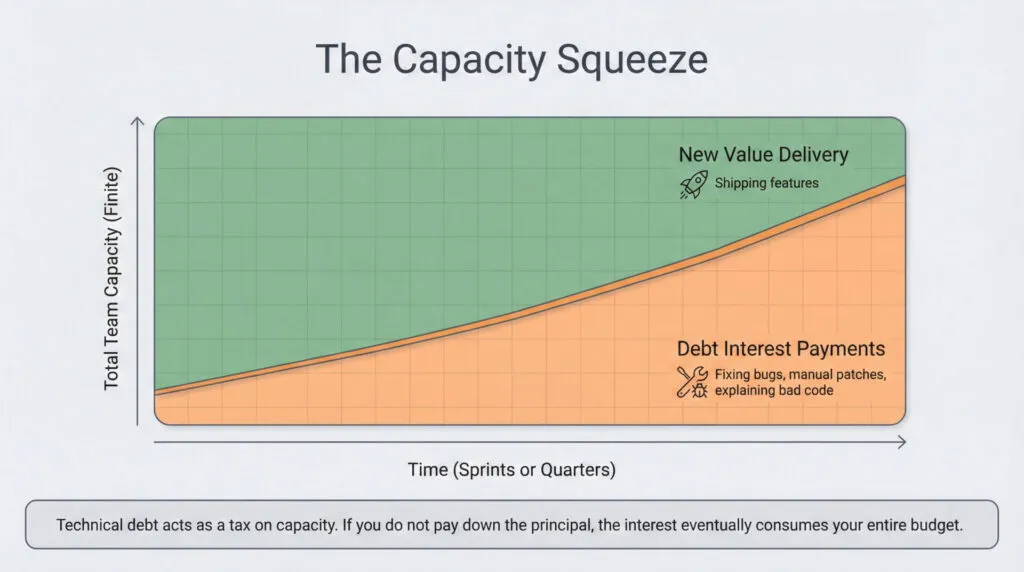

This experience also taught me something fundamental: systems built on heroics are brittle. Organizations that depend on people saying yes to high-risk deployments without building institutional capacity to protect them will eventually break the people who make those systems work.

This is why I now design for capacity, not heroics. I’ve seen what happens when the “can-do spirit” becomes a substitute for redundant deployment, accurate risk assessment, and long-term accountability. It works until it doesn’t. Then it breaks people.

You can read the full story and the doctrine that emerged from it in the field note: Systems Built on Heroics Are Brittle.

Why I Work This Way Now

The through-line that connects grad school, Katrina, federal systems work, and Hurricane Florence is this: I build forward-deployed capability that serves teams making decisions under real constraints, and I document what works so it can survive without me.

That shows up in how I work today:

Forward-deployed, not ivory tower

I learned from Katrina that architecture done from a distance, without understanding how teams actually operate, produces systems that look good on slides but fail under pressure. I embed with teams, understand their constraints, and build systems that fit their reality.

Doctrine-driven

Every field note and guide on this site comes from real work in high-consequence environments. These aren’t theoretical frameworks. They’re patterns that survived contact with reality: federation over integration, two-lane architecture, capacity over heroics, named stewards instead of anonymous “IT.”

Dialogue over monologue

My work is centered on collaborative, stakeholder-heavy dialogue (rather than one-way panel interviews) where problems get solved through iterative refinement.

What This Means for Working With Me

If you’re dealing with high-tempo systems, messy portfolios, or mission-critical work that needs architecture under real constraints, the Interpreter Kit explains how we might work together. That page is designed for people who know my work and want to introduce me to their networks.

If you’re evaluating me for a role and wondering whether my background matches what you need, consider:

- I’ve built and supported systems that had to work under pressure: disaster response, federal infrastructure protection, coalition environments, high-tempo operations.

- I’ve operated in contexts where failure had real consequences: wildland fire, hurricane response, aviation-adjacent work, geospatial C2 for critical infrastructure.

- I’ve led teams, built institutional capability, and documented systems so they could survive after I moved on.

- Stakeholder management, collaborative problem-solving, architecture that accounts for political and technical constraints.

If you just want to understand how I think, start with the Field Notes. They show the pattern better than any resume could.

The Mobile Mapping Unit story shows how forward-deployed capability works.

The Katrina Book story shows how narrative infrastructure serves teams.

The Hubbard Brook story shows how to guard the room in high-stakes conversations.

And the Systems Built on Heroics story shows why capacity matters more than heroics, and why evaluation systems don’t always test for the right things.

Where Things Stand Now

“In early 2025, my federal position was eliminated as part of workforce restructuring. My entire division was removed.

My former Forest Service supervisor now works for a federal contractor. She hired me onto her team because she knows what I can do. She’s seen me do it, and I’m grateful for her continued support.”

I am now deploying this capability to organizations that need: forward-deployed architecture for high-consequence systems, stakeholder management in complex environments, and the kind of collaborative problem-solving that emerges through dialogue rather than performance under observation.

This approach bypasses the usual vendor theater and gets straight to the ground truth of your portfolio: it is designed for leaders who need results that survive contact with reality (not just slides that look good in a boardroom).

If that sounds like what you need, or if you know someone who does, the Interpreter Kit is the best place to start.

A Note on Publication Dates and Archival Work

These field notes and doctrine guides draw from twenty years of work (2005-2025). Some pieces were written years ago when the experiences were fresh and captured in Word docs or internal reports but never published. Others were written recently as I’ve gained the distance to see patterns I couldn’t articulate at the time.

You may notice evolution in my voice and clarity across pieces. That’s because they were written at different points in my career. Publication dates reflect when I made the work public, not when the experience happened or when I first documented it.

I’m publishing now because I finally have the platform and capacity to make these patterns useful to others. The work has been there. The documentation has been accumulating. This is me hitting publish.

I utilize the term ‘Doctrine’ as a professional tribute to the rigor of formal institutional frameworks. My intent is not to replicate or replace official Publications; rather, I believe that high-stakes operational experience deserves a similarly disciplined structure. By packaging these lessons as ‘Doctrine,’ I ensure they are codified, repeatable, and ready for the next practitioner to inherit: fulfilling the primary obligation of Interface Stewardship