Companion to: Doctrine 21: Zero Trust Is A Trust Model, Not A Card “Type”

This page is a Doctrine Companion. It hangs off Doctrine 21 and gives you a shared vocabulary for identity and access in Microsoft 365, so that zero trust conversations do not dissolve into word salad.

Use it when you are:

- Designing access patterns in Microsoft 365

- Reviewing architectures and audits

- Trying to untangle confused conversations about claims, groups, roles, or entitlements

Don’t reach for this companion if:

- You’re just enabling basic MFA for your organization

- You’re troubleshooting a single user’s access issue

- You’re implementing a simple “everyone in group X gets access to app Y” pattern

This companion is for complex authorization patterns, cross-tenant scenarios, and zero trust architectures that need precise vocabulary.

Core Idea #

Zero trust needs more than strong cards and good VPNs. It needs clear answers to basic questions:

- What facts about a user or device do we trust enough to build policy on?

- Where do those facts live?

- How do those facts show up at the moment of an access decision?

In Microsoft 365, those answers live in a small stack of concepts:

- Claims: facts in the token

- Groups and roles: how we bundle people and workloads

- Entitlements: specific rights to specific resources

- Policies and enforcement points: where zero trust decisions are made

If a team uses these words loosely, zero trust quietly collapses back into perimeter thinking and card worship.

1. Why This Companion Exists #

Doctrine 21 reminds you that zero trust is a trust model, not a card type or a product logo. CAC, PIV, smartcards, and MFA apps are strong identity signals inside that model. They are not the model itself.

In practice, many organizations still treat:

- “claims”

- “groups”

- “roles”

- “entitlements”

- “policies”

as if they are interchangeable. That confusion shows up as:

- Access reviews that cannot explain why someone has a given permission

- Security proposals that talk about “zero trust” but never identify which signals are being evaluated

- Architectures where identity tech is purchased, but authorization is still driven by a handful of static groups

This companion exists to:

- Define claims, roles, groups, entitlements, and policies in a consistent way

- Show how those pieces work together in Microsoft 365 and Entra ID

- Connect that stack back to the zero trust model in Doctrine 21

The goal is not to cover every Microsoft feature. The goal is to give you a vocabulary that makes real zero trust designs possible.

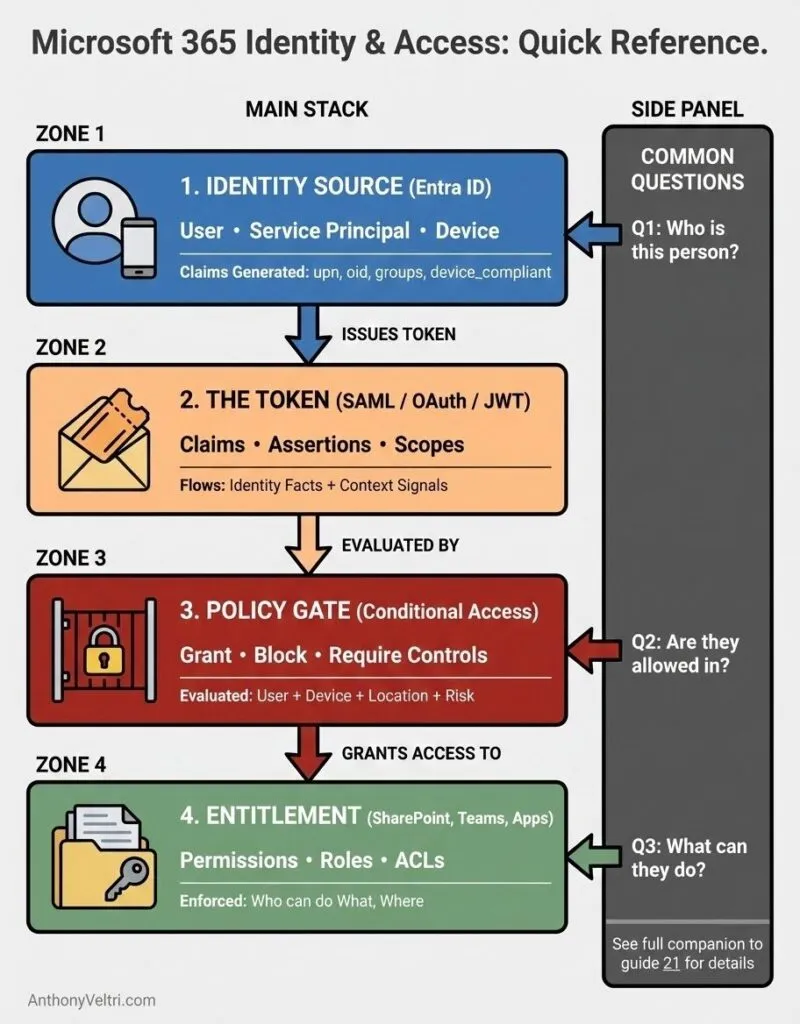

2. The Identity and Access Stack in Microsoft 365 #

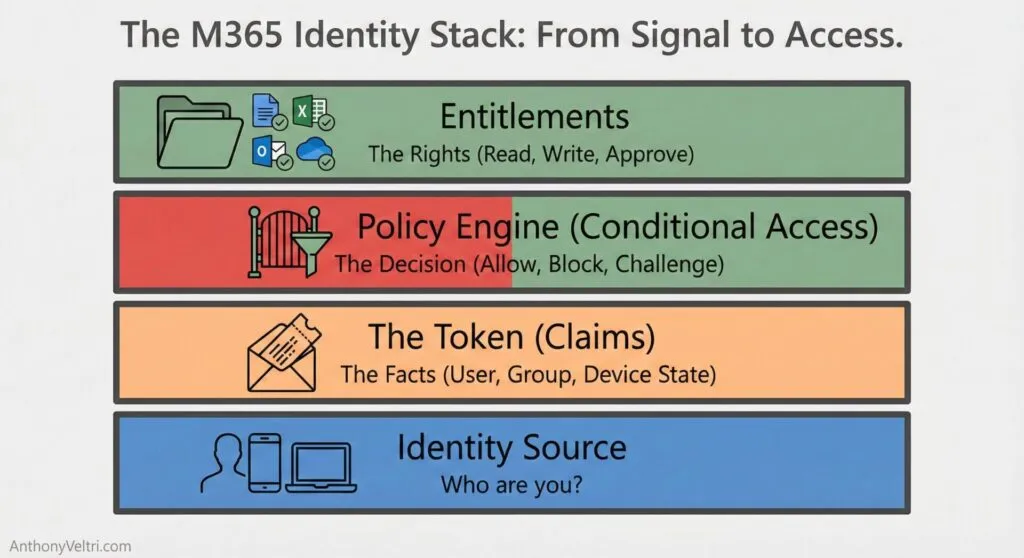

At a high level, Microsoft’s cloud identity story looks like this:

- Entra ID issues security tokens that contain claims

- Applications and services read those claims and make decisions about access

- Groups, app roles, directory roles, and entitlements drive which claims appear and how they are interpreted

- Conditional Access acts as a zero trust policy engine that combines signals and enforces decisions

Don’t Confuse the Person with the Permission.

This section describes each layer in practical terms.

2.1 Claims: Facts Inside a Token #

A claim is a statement about a subject, carried in a token. Examples:

upnoremail: who the user isgroups: which security groups the user belongs toroles: which app roles or directory roles are assigneddevice_compliant: whether the device meets policyauth_time: when the user last authenticated- custom attributes such as

clearanceLevel,country, orbusinessUnit

You can think of a token as a sealed envelope delivered to an application. The envelope proves who issued it. The claims inside describe who or what the subject is, and under what conditions.

Working rule:

Claims are facts, not permissions. They do not grant anything by themselves. They are inputs to policy.

2.2 Groups and Roles: How People and Workloads Are Bundled #

Groups and roles give structure to claims:

- Security groups

- Collections of users or service principals

- Often emitted as

groupsclaims if the token is sized appropriately

- Directory roles (Entra roles)

- Administrative roles such as Global Administrator or Security Reader

- Often emitted as role claims in tokens

- App roles

- Application specific roles defined on a resource

- For example:

Report.Reader,Report.Contributor,Case.Reviewer

Groups and roles are how you avoid targeting policies at individual accounts. They let you say:

- “All members of the Anesthesia Clinicians group”

- “Anyone in the Finance Approver app role”

- “Any workload identity that has the BackupAgent role”

Working rule:

Groups and roles describe who a policy applies to in human terms, so that tokens can carry the corresponding claims.

2.3 Entitlements: Explicit Rights to Specific Resources #

An entitlement is a concrete decision that grants a subject a specific right to a specific resource under defined conditions.

For example:

- Read access to a SharePoint site that hosts engineering specifications

- Approval rights in an expense management app

- The ability to modify a subset of patient records under a defined jurisdiction

Microsoft products represent these decisions in different ways:

- Access control lists on SharePoint sites and libraries

- Membership in app roles or security groups that gate an application

- Assignments in Entra Entitlement Management packages

Underneath the variety, the pattern is simple:

Working rule:

Entitlements answer the question “Who can do what, where, and under which conditions.”

2.4 Policies and Enforcement Points #

Policies decide when and how claims and entitlements are evaluated.

Key policy surfaces in Microsoft 365 include:

- Conditional Access: Combines signals from user, group, device, location, and risk to grant or block access, or to require controls such as MFA or device compliance.

- Application specific authorization: Logic inside SharePoint, Teams, Power BI, and custom apps that interprets claims and entitlements.

- Data protection policies: Sensitivity labels, DLP, and conditional access app controls that govern how data can be used, not only who can see it.

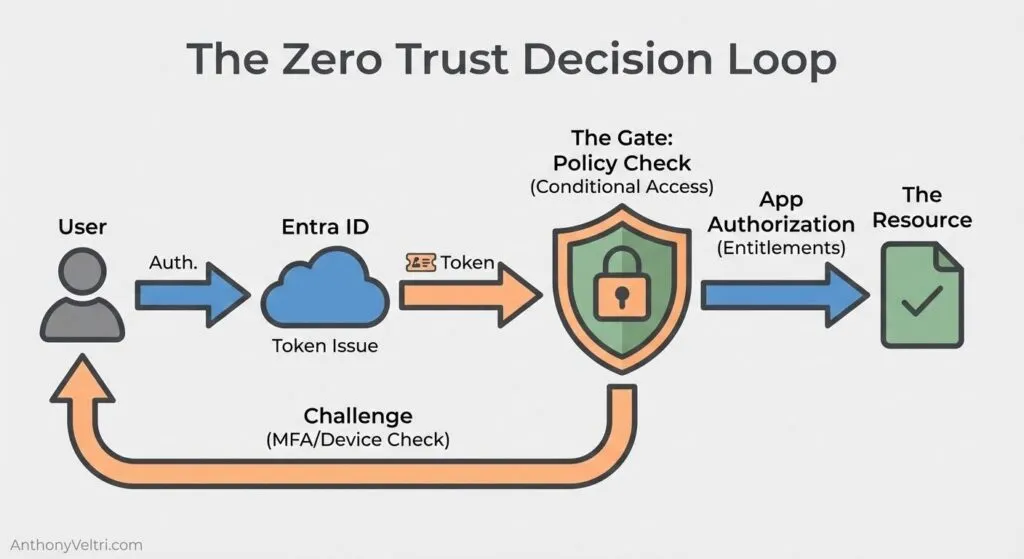

Zero Trust Is a Loop, Not a Badge

Working rule:

Policy is where zero trust lives. Claims and entitlements have value only because policy engines interpret them and enforce decisions.

3. Claims That Matter in Real Systems #

There are thousands of possible claims. Very few should be central to your zero trust design.

In practice, a small, stable set of claims does most of the heavy lifting. You can map these across many industries: public sector, health care, manufacturing, financial services, higher education, and others.

Here is a practical list of eight claim categories that show up again and again.

3.1 Identity and Organizational Placement #

- Who the subject is: Claims such as

sub,oid,upn, andemail. These are the anchors that tie tokens back to a directory entry. - Organizational placement: Business unit, department, or command.

- For example:

businessUnit = Cardiology,department = Treasury,command = RegionalOperations

- For example:

These claims support:

- separation of duties

- allocation of costs and licenses

- targeted access to data that belongs to a given unit

3.2 Job Function and Role #

- Job function: Human understandable descriptors such as

jobTitleorjobFunction.- For example:

jobFunction = AirPlanner,jobFunction = ChargeNurse,jobFunction = FinanceAnalyst

- For example:

- Application or directory roles: Machine readable roles such as

Report.ReaderorCase.Revieweremitted as claims.

These drive authorization patterns such as:

- “Charge nurses can see ward level dashboards”

- “Case reviewers can approve high value payments”

3.3 Data Sensitivity and Clearance #

- Data sensitivity or clearance level: Claims such as

clearanceLevelordataAccessTier.- For example:

clearanceLevel = Confidential,dataAccessTier = HighlyRestricted

- For example:

These become critical wherever:

- legal or regulatory requirements differ by data tier

- cross organization or cross border collaboration needs tight control

3.4 Location and Jurisdiction #

- Location and jurisdiction: Claims for physical or legal context, such as country, region, or site.

- For example:

country = DE,region = EU,site = DC01

- For example:

These support policies such as:

- “Data for EU residents is visible only to staff operating under EU jurisdiction”

- “Operators in one region can monitor another, but cannot change configuration there”

3.5 Device State and Compliance #

- Device identity and compliance: Claims that indicate whether the device is joined, registered, or compliant with policy. Intune and partner mobile device management (MDM) systems feed this information into Entra ID, which Conditional Access policies evaluate. (MDM systems ensure mobile devices within an organization comply with applicable standards and policies.)

These claims make it possible to say:

- “Even if a user passes MFA, they must still be on a compliant device to access tier one systems”

- “External collaborators can use their own devices, but only through constrained experiences”

3.6 Risk and Session Context #

- Risk level: Claims derived from sign in risk, unusual behavior, or detection systems.

- Session context: Claims related to sign in time, client type, or authentication strength.

These enable decisions such as:

- “Read access is allowed from medium risk sessions, write access is not”

- “Highly privileged operations require a higher authentication strength”

3.7 Environment and Tenancy #

- Environment or zone: Claims or configuration that distinguish production from test, or core tenant from partner tenants.

These are essential when:

- multiple environments share an identity backbone

- there are cross tenant trust relationships, such as business to business collaboration scenarios

4. From Claims to Zero Trust Decisions #

Zero trust in Microsoft 365 is not an abstract slogan. It appears in very specific moments when a user or workload requests access and a policy engine evaluates the claims.

This section walks through a simple request flow.

4.1 One Request, From Start to Finish #

Imagine a user in any sector trying to open a sensitive document, such as:

- a clinical protocol in a hospital

- an engineering design in a manufacturing firm

- a planning document in a government agency

At a high level:

- Authentication: The user proves identity through one or more methods such as password, smartcard, CAC, or FIDO key, possibly with MFA.

- Token issuance: Entra ID issues a token with claims describing who the user is, how they authenticated, and relevant groups, roles, and device properties.

- Conditional Access evaluation: The Conditional Access engine evaluates the token and other signals (user, group, location, device compliance, risk level).

- It decides whether to: grant access, require additional controls such as MFA or compliant device, or block access entirely.

- Application authorization: The application (for example SharePoint, Teams, or a line of business app) interprets entitlements: which site, library, or workspace the user can reach, and which actions are allowed.

- Data protection and monitoring: Data loss prevention, sensitivity labels, and application controls may further constrain what the user can do with the content, even after access is granted.

At each step, claims supply facts. Policies and entitlements supply decisions.

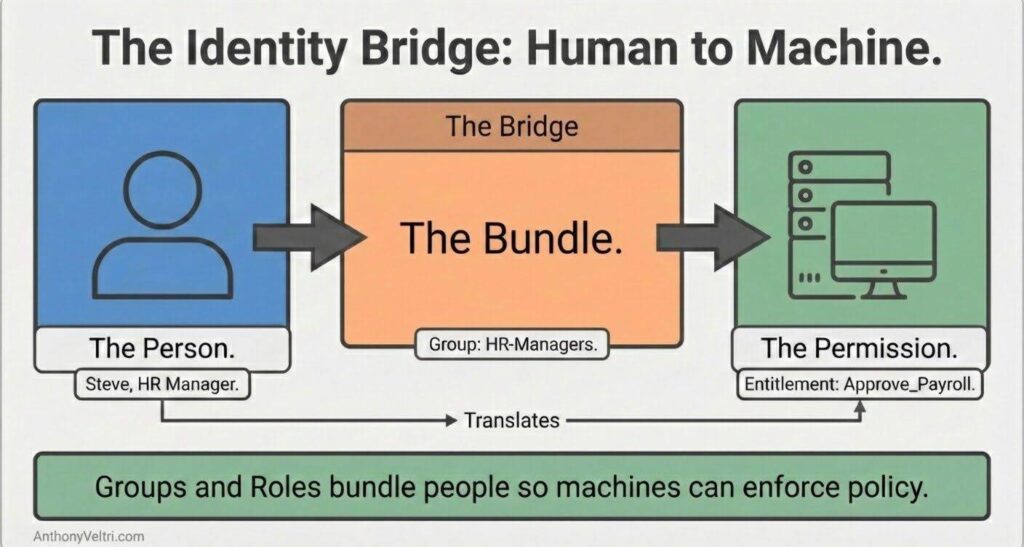

The Translation Layer

4.2 How This Supports Doctrine 21 #

Doctrine 21 tells you to stop treating identity tech as the model and to focus on repeated access decisions at every door.

The claim stack described here provides the raw material for those decisions:

- identity, device, and risk claims feed Conditional Access

- group and role claims feed application specific authorization

- custom claims such as clearance or jurisdiction guide fine grained decisions

Taken together, this is how Microsoft 365 implements the hotel model from Doctrine 21, where the key card is checked at each door, not only at the front gate.

5. Patterns and Pitfalls for Designing Claims #

This section gives patterns that travel well across organizations, along with the most common ways they fail.

5.1 Pattern: Small, Stable Core Claims #

Good zero trust designs concentrate on a small, stable set of claims that are:

- well defined

- backed by authoritative systems such as HR or MDM

- suitable for use in many policies and applications

Examples: businessUnit, jobFunction, clearanceLevel or dataAccessTier, region or jurisdiction, device_compliant.

Pitfall: creating dozens of free text attributes that are never cleaned up, then discovering that policies depend on values that no one can confidently interpret.

Working rule:

Prefer a small, stable vocabulary of core claims backed by reference data, rather than a large, drifting set of attributes that no one trusts.

5.2 Pattern: Groups and Roles as Bridges Between People and Claims #

Use groups and roles to bridge from human concepts to machine enforcement.

- Define groups and app roles around real work: “Ward Charge Nurse”, “Regional Sales Manager”, “Airspace Planner”.

- Map those to policies and entitlements: “Can approve up to this threshold”, “Can edit plans in these regions”.

Pitfalls:

- building giant “everyone in department X” groups that end up with broad access to unrelated systems

- using roles that sound similar but do not match real job responsibilities

Working rule:

Design groups and roles to reflect actual responsibilities, not directory convenience.

5.3 Pattern: Claims From Authoritative Sources Only #

Treat certain systems as the source of truth for specific claims:

- HR or directory for identity and job function

- MDM for device compliance

- Governance systems for clearance or data tier

Pitfalls:

- allowing multiple systems to update the same claim, leading to conflicts

- using manual updates in production for anything that must withstand audit

Working rule:

Each core claim should have one primary steward and a clearly identified source of truth.

5.4 Pattern: Cross Tenant Trust as Explicit Decisions #

In federated or cross organization environments, treat external claims with care.

For example:

- decide which external MFA signals you are willing to trust

- decide whether external device compliance claims are accepted, and under what conditions

Pitfalls:

- trusting external claims by default, without a clear policy

- ignoring external claims entirely, then recreating work that partners have already done

Working rule:

Trust external claims when there is a clear agreement and monitoring, not as an accident of federation.

6. Language Checklist #

This checklist gives you short definitions you can drop into architecture documents, policies, or design reviews. You can treat this as a reusable snippet.

- Claim: A fact about a user, device, or workload, carried in a token.

- Example: user identifier, group membership, device compliance, clearance level.

- Group: A collection of identities used to target policy and entitlements.

- Example: “Oncology Clinicians”, “Regional Finance Approvers”.

- Role: A named responsibility or capability, often scoped to an application or directory.

- Example: “Report.Reader”, “Case.Reviewer”, “Security Administrator”.

- Entitlement: A concrete right to perform a specific action on a specific resource.

- Example: “Can approve payments up to a threshold in this system”, “Can modify these datasets”.

- Policy: A defined rule set that evaluates claims and context to allow or block access, or to require controls.

- Example: Conditional Access policies, application authorization rules, or data protection policies.

- Zero trust decision: A repeated, per request evaluation of identity, device, context, and entitlements that does not assume that being on the network implies trust.

Working rule:

When someone uses one of these terms in a review, you should be able to point to the corresponding implementation: the claim, group, role, entitlement record, or policy definition.

7. Companion Diagnostic: Review Questions #

You can use these questions alongside the Doctrine 21 checklist when reviewing a system, portfolio, or architecture. If you cannot answer them cleanly, you are at risk of zero trust theater.

- Claims inventory: Which claims do our critical policies rely on? For each claim, what is the system of record?

- Group and role clarity: Can we describe our key groups and roles in plain language that matches how people actually work? Do we have broad “catch all” groups that undermine least privilege?

- Entitlement transparency: For a given high value system, can we answer: “Who can do what, where, and under which conditions?” Can we show how that answer is implemented in Microsoft 365?

- Policy visibility: Do we know which Conditional Access policies and application rules gate access to critical systems? Can we explain which claims each policy evaluates?

- Lifecycle and drift control: How fast do claims, group memberships, and entitlements update when people change jobs or devices? Who is responsible for cleaning up stale access?

- Cross tenant and partner trust: Where do we trust external identity providers or device claims? Are those trust decisions documented and monitored?

If these questions reveal gaps, return to Doctrine 21. Use the doctrine to reframe the conversation around repeated access decisions, then use this companion to align the vocabulary that makes those decisions possible.

Field notes and examples #

Last Updated on December 14, 2025