Field Guide: Disconnected Editing Is Not a GIS Feature. It Is a Survival Pattern.

Most enterprise systems are designed like the network is a law of physics.

Field work teaches the opposite.

Signal drops. Bandwidth lies. Security domains get segmented. And the mission still moves forward.

Back in the 2008 era, (before ESRI was officially Esri) Esri’s disconnected editing and replication workflows felt like the greatest thing ever because they acknowledged that reality. It was not perfect. Sync could be ugly. Delta reconciliation could be ugly. But it beat the only alternative we had at the time: manual merge chaos.

The real value was never “a GIS capability.”

The value was the pattern.

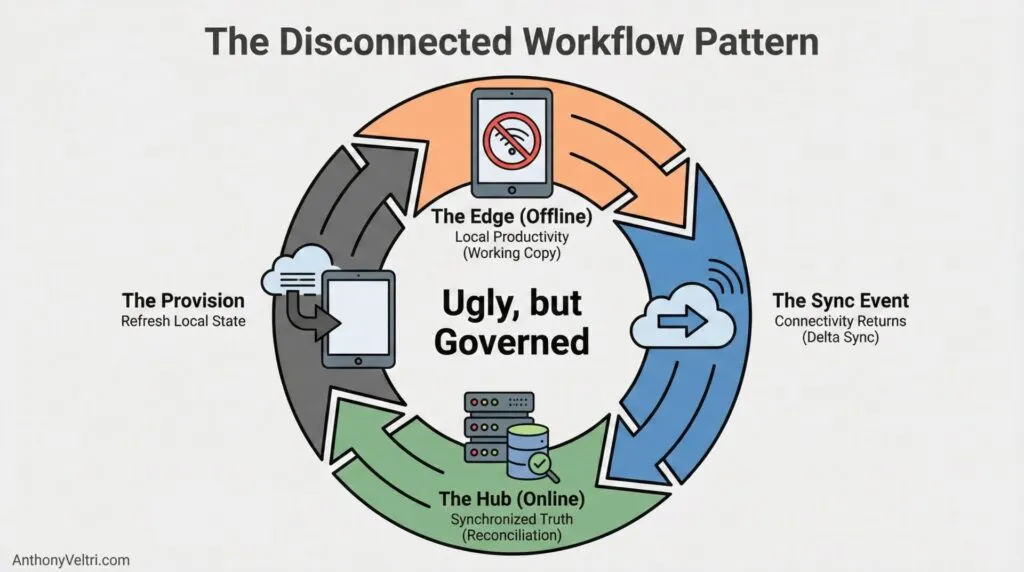

The pattern in one sentence

Local productivity now. Synchronized truth later.

If you remember nothing else, remember that.

Why this mattered then, and why it matters now

Disconnected editing solved a problem that is bigger than maps.

When people are working at the edge, they need a local working copy that lets them operate without waiting for the mothership.

Then, when connectivity returns, the system needs a disciplined way to reconcile reality back into an authoritative dataset.

That same reality now shows up in:

- Field inspections and mobile forms

- Remote project sites

- Disaster response

- Segmented security environments

- Collaboration platforms where content needs to feel local even when the network is not

The label changes. The constraint does not.

A vignette from the real world

When I ran geospatial capability inside DHS NPPD, we constantly had to translate this pattern across partners and environments. Federal, state, local, tribal, and mission partners. Different networks, different constraints, different operational tempo.

CBP had a very specific version of the same problem: field teams needed to keep working without reliable connectivity, and the edits still had to land cleanly back into the authoritative system.

The reason this mattered was not technical vanity. It was integrity.

Manual merging into a golden dataset is slow, error-prone, and basically guaranteed to create silent errors under pressure.

Disconnected workflows took messy human reality and routed it through a governed pipeline.

Ugly, but governed.

The key principles

1) The edge is an operating environment, not a client

If people must work without signal, the edge has to be capable of real work. Not view-only until internet returns.

Field example:

- A crew captures observations and edits features offline, then syncs when they hit coverage.

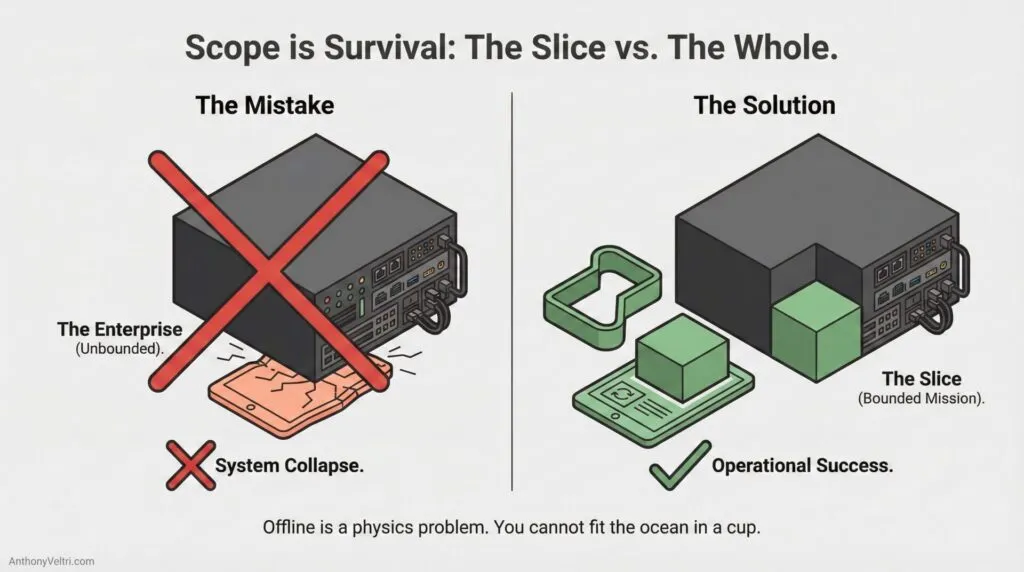

2) Scope is everything

You cannot take “the enterprise” offline. You take a slice.

Field example:

- A utility crew takes only assets and work orders for a territory, not the national dataset.

If you do not bound scope, offline becomes a myth that collapses under its own weight.

3) Sync is a workflow, not a button

This is where most systems lie to users.

If synchronization is treated like a casual afterthought, the system becomes dependent on memory, habits, and heroics.

Field example:

- End-of-shift sync is standard procedure.

- Sync health check is part of the checklist.

- Failed sync has an escalation path, not a shrug.

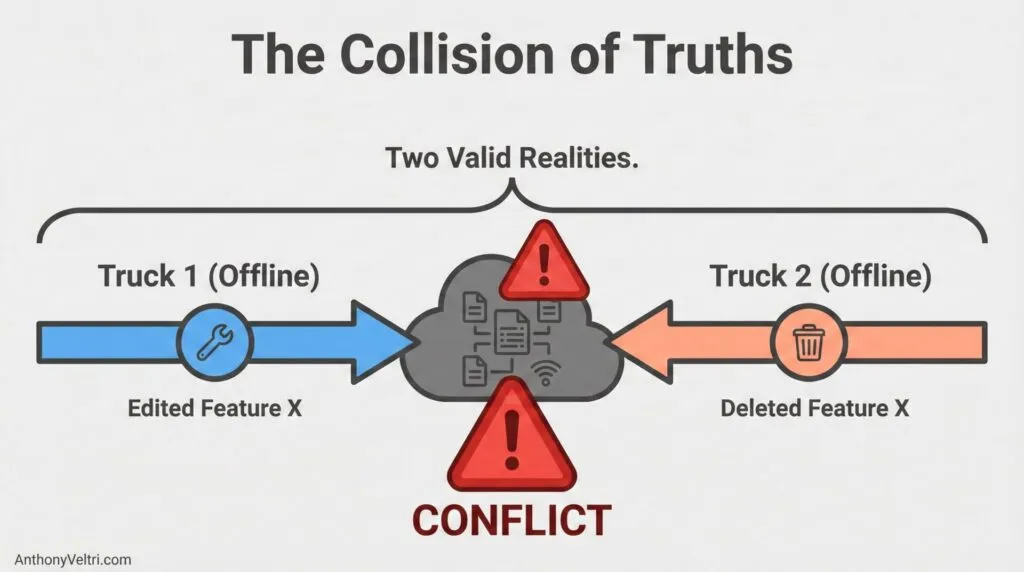

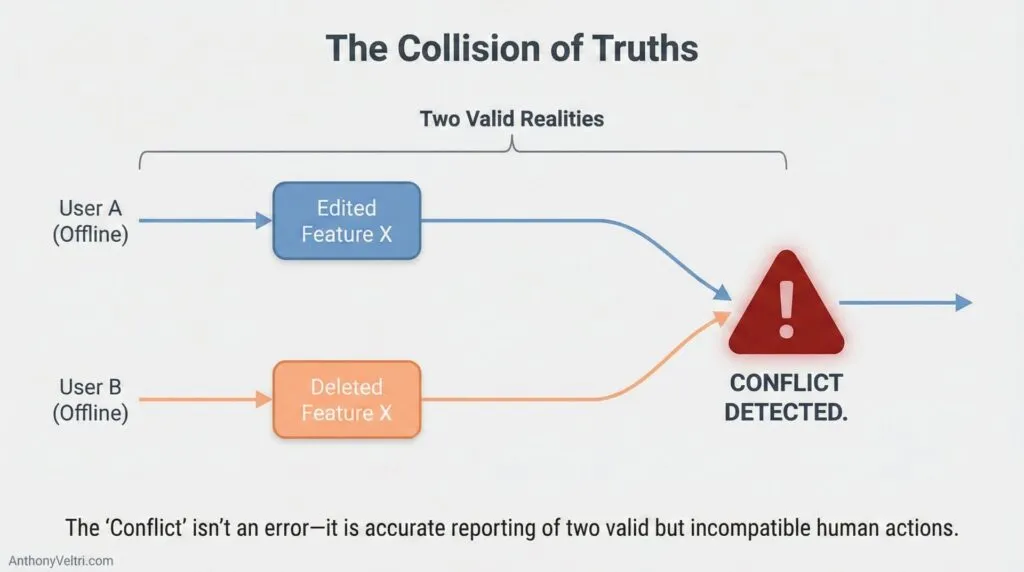

4) Conflicts are not bugs. They are math.

If two people can edit the same thing independently, conflicts are inevitable.

The mistake is not having conflicts. The mistake is pretending you will not.

Field examples:

- Two inspectors edit the same asset attribute differently.

- A supervisor updates centrally while a field crew edits offline.

A mature system defines:

- What conflicts look like

- Who decides

- What gets automatically resolved

- What requires review

5) Truth needs an operating model, not a file

Everybody wants a golden dataset. What they really need is a golden process.

That process includes:

- Clear authority boundaries

- Defined sync cadence

- Conflict policy

- Auditability

- A way to see what is pending, failed, or diverged

If you cannot see the sync state, you do not have a system. You have a rumor.

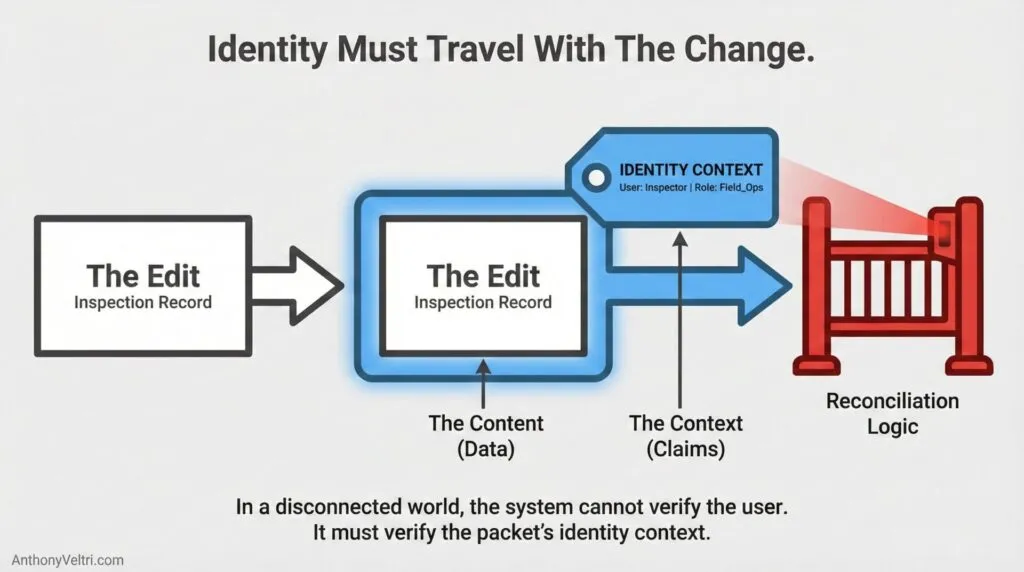

Today’s translation: why disconnected workflows always turn into a claims problem

The quiet truth is this. In a connected system, the server trusts the connection. In a disconnected system, the server must trust the packet. As soon as you let people work locally and sync later, you are not just moving data around. You are moving authority.

And authority is always an identity problem.

In Microsoft 365 terms, this is where claims stops being an abstract security topic and becomes the control plane for everything that happens next.

In a connected system, trust rides the session. In a disconnected system, trust has to ride the payload.

Disconnected systems do not get the luxury of a live session. Edits show up later, sometimes as a file transfer, a queued message, or a replication delta that lands hours after the work happened.

When that change arrives, the server cannot lean on “who is currently logged in” or “what the connection says” because there is no connection to consult. It has to validate the change based on what travels with it: who performed the action, what they were entitled to do at the time, when the change was made, and whether anything was altered in transit.

That is why disconnected workflows always turn into a claims problem. At sync time, the server must answer five questions before it accepts anything into the authoritative system: who created this change, under what entitlements, is the change intact, is it still acceptable to apply now, and can I audit it end to end.

Those are identity and authorization questions. Claims are the compact way to carry that authority across time and distance, and signed, auditable envelopes are how you make the system trustworthy when the network is not.

The mapping

Here is the clean mapping from the geodatabase era to the M365 era:

- Offline replica becomes a local copy of content or state that must remain usable without reaching a central service.

- Sync deltas become change messages that need to be trusted, audited, and applied in the right order.

- Conflict resolution becomes who is allowed to win when two truths collide.

- Golden dataset becomes authoritative service state, not just data.

- Editor permissions become claims and entitlements that define what actions are legitimate.

The pattern does not change. The nouns change.

Why claims matters specifically in disconnected or replicated workflows

Claims are how a system answers: who is this, and what are they allowed to do right now?

In a connected world, the system can verify that continuously.

In a disconnected world, you have to decide what you trust locally, what you defer, and what you re-validate at sync time.

That creates three decision points that always show up, even when people pretend they will not.

1) What is enforced locally vs enforced at sync

Some rules can be enforced offline. Some rules cannot.

Example:

- A field user can create a record offline.

- But promotion of that record into authoritative truth might require a different claim, or a review gate, when the system is back online.

This is where people get confused, because they treat offline as it is done, when in reality it is staged.

2) Permissions must travel with the change

A delta without an attached identity context is just a blob of edits.

The system needs to know:

- Who made the change

- Under what entitlement

- Whether that entitlement was valid at the time

- Whether that change is still permissible when it lands back in the authoritative system

Permissible then and permissible now are not always the same thing.

3) Auditability prevents ghost edits

Once you have replication, you create distance between action and verification.

So the system needs receipts:

- Who did what

- When they did it

- What they changed

- What happened during reconciliation

- What was rejected, and why

Without that, you do not have integrity. You have plausible deniability.

A modern example in the collaboration world

This same pattern shows up in SharePoint replication tooling. For example, iOra Geo-Replicator is designed to maintain local replicas of SharePoint content for remote and bandwidth-constrained environments, then synchronize changes back to central SharePoint later. The product details are not the point. The pattern is: local productivity, delta movement, conflict handling, and operational visibility.

Failure modes that show you do not actually have the pattern

These are the tells.

Offline is supported but nobody knows if they are synced

You get silent data debt.

Just export it becomes the default workflow

You get uncontrolled copies and untraceable truth.

Conflict is handled only when it explodes

You get last-minute arbitration under pressure.

Scope is unlimited

Offline packages become fragile, slow, and inconsistent.

Practical checklist for field work with weak signal

If you want disconnected workflows to be real, not aspirational:

- Define the minimum offline slice.

- Define the sync cadence.

- Define the conflict policy.

- Make sync state visible.

- Treat sync failures like incidents.

- Train the workflow like it is part of the mission, because it is.

Closing: the memory hook

If you see a system that must function when the network is uncertain, always look for the identity and authority model underneath it.

If you see offline replicas, cached work, or delayed synchronization, always ask:

Who is allowed to change what?

When is that permission enforced?

How is it audited?

What happens when two truths collide?

Because disconnected work is not a feature.

It is a trust problem with a synchronization schedule.

Last Updated on January 17, 2026