Field Note: When You Call a Committee a Team

Why Mislabeling Group Types Breaks Decisions

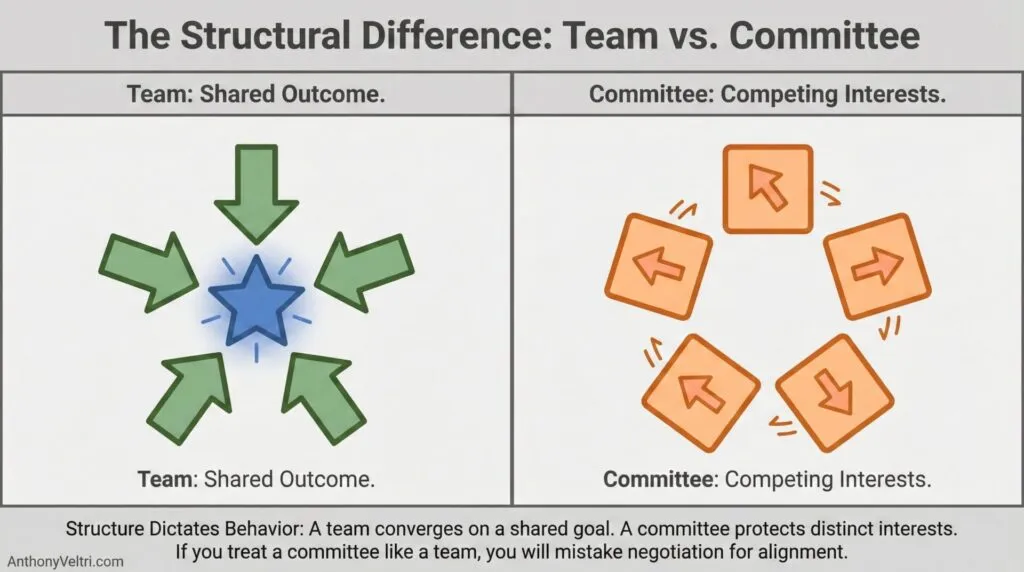

People use “team” and “committee” as if they mean the same thing. They do not. A team is built for shared outcomes. A committee is built to manage competing interests. Confusing them creates conflict, delays, and sometimes failure.

I learned this during a trip to the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest, captured in my piece “Guarding the Room” which you can find on this site.

What the Drive to Hubbard Brook Taught Me

During that trip I interviewed scientists about their work and how they present it. One senior scientist gave me a ride north. She was preparing for a high stakes funding meeting with decision makers who would determine whether her long running research would continue.

On the drive she talked through her message and the kinds of questions she expected. I listened and asked if she wanted to test her framing. She agreed.

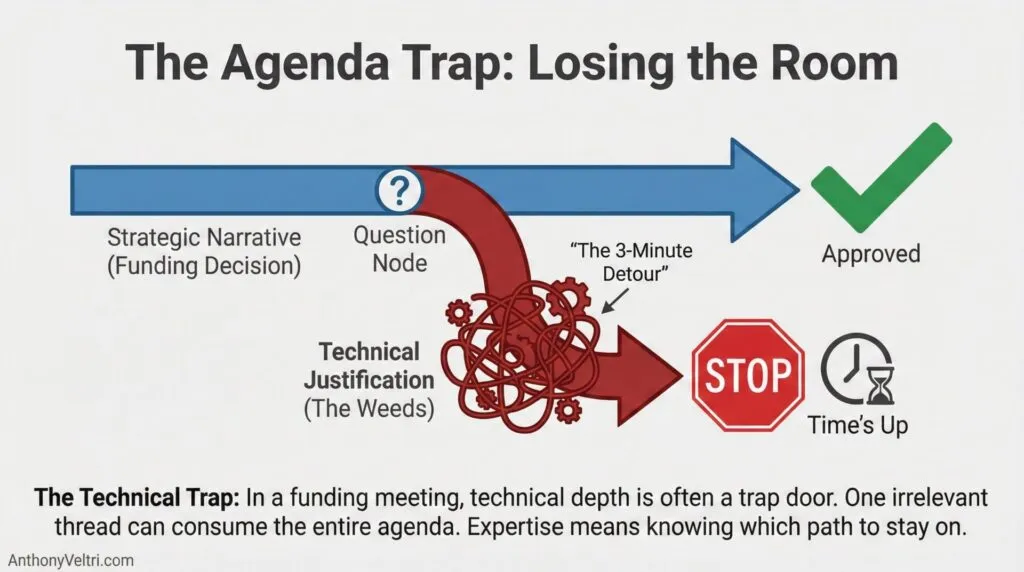

When she made her pitch, I asked a single technical question about why she chose a specific oxygen isotope for her analysis. She knew this kind of question was likely to appear, yet her instinct took over. She shifted into full technical justification. In less than three minutes the available time was gone. Her main point never resurfaced.

It was uncomfortable to watch and it stayed with me. She was brilliant. She was prepared. She was also conditioned by years of scientific culture to treat any question as a technical challenge that must be answered in depth.

In a peer review setting that instinct is rewarded. In a funding meeting it can be fatal. One irrelevant thread can consume the entire agenda. That interaction taught me that technical expertise and decision room expertise are different skill sets.

The Structure Problem

Her upcoming meeting was not a team discussion. It was a committee like environment. People in the room had different goals, different pressures, and different thresholds for risk. They were not gathered to co create a shared outcome. They were gathered to decide whether to invest scarce resources.

Treating a committee like a team creates predictable failure modes.

Here is what happens when the structure is misnamed:

- You assume shared outcome alignment where none exists.

- You expect execution behaviors in a setting built for deliberation.

- You let technical detail dominate time reserved for strategic framing.

- You lose control of the narrative because you assumed the wrong type of room.

The Hubbard Brook moment made this pattern hard to ignore. The wrong label leads to the wrong posture. The wrong posture leads to the wrong outcome.

Mislabeling Risks Ranked by Severity

Some terminology errors are harmless. Others can derail entire efforts. Here is the ranking from most destructive to least.

1. Committee treated as a team

A committee exists to represent and negotiate between distinct interests. Members are present because they hold different mandates, budgets, or constituencies. The structure acknowledges that alignment must be negotiated, not assumed.

This is the most dangerous mislabeling. Conflicting incentives get hidden under a veneer of unity. People expect cooperation where they should expect negotiation. This creates decision drag and political stall. The real work never begins.

2. Governance group treated as a team

A governance group holds decision rights and accountability oversight, but does not execute the work directly. Their job is to set boundaries, approve direction, and ensure accountability structures exist.

Decision rights get fuzzy. Leaders start managing work directly. Teams wait for approvals that never come. Momentum collapses.

3. Delivery team treated as a committee

A delivery team exists to execute shared work toward a concrete outcome. Members are accountable for results, not for representing external interests.

Execution groups begin acting like representatives instead of doers. Ownership diffuses. Delivery slows to a crawl.

4. Alignment treated as consensus

Alignment means everyone understands the direction and can work within it, even if they wouldn’t have chosen it. Consensus means everyone must agree before movement happens.

Every person acquires veto power. Movement shrinks to the pace of the most hesitant voice.

5. Ownership treated as involvement

Ownership means a specific person or team holds accountability for outcomes and has authority to make decisions. Involvement means being consulted or informed, without bearing the weight of the result.

Everyone is consulted. No one is accountable. The work quietly falls onto whoever cares the most.

6. Strategy treated as tactics

Strategy defines what you’re trying to achieve and why it matters. Tactics are the specific methods and tools used to execute.

Debates explode around tools, formats, and details because the real disagreement about purpose was never surfaced.

The Practical Fix: Guard the Purpose of the Room

The lesson from Hubbard Brook was simple. Before you step into any critical meeting, name the room. Is it a team space or a committee space.

Both are valid. What matters is choosing the right posture.

In a team space you build together.

In a committee space you frame, influence, and negotiate.

If a technical question is not tied to the actual decision in front of the group, acknowledge it briefly and return to the purpose. This is not evasion. It is agenda protection.

The scientist on that drive had the right message. What she needed was the right frame for the room she was walking into. Seeing how easily she could be pulled off mission made the lesson clear for me too.

Related Notes

Doctrine 10 Companion: The Invisible Buffer: When one person absorbs everyone’s uncertainty

Guarding the Room: A Hubbard Brook story about science and funding

Last Updated on December 14, 2025