Why I Kept Quiet: A Field Note on the Stewardship of Operational Knowledge

Stewardship of Operational Knowledge – On Finally Documenting What I Know

A personal reflection on the transition from hiding to documenting.

The Silence

For 20 years, I kept quiet about what I knew.

I had the knowledge. I saw the patterns. I understood things that only emerge from sustained operational exposure in federal disaster response, enterprise systems architecture, and partnership coordination in complex international contexts. I built systems that are still running today. I made calls under pressure. I watched what worked and what failed when the stakes were real.

But I didn’t write about it. Didn’t speak about it publicly. Didn’t claim authority over my own experience.

Not because I was lazy or scared, but because I genuinely believed I didn’t have the right.

This field note is for the person standing in the EOC twenty years from now, so they don’t have to relearn what I learned the hard way.

The False Permission Structure

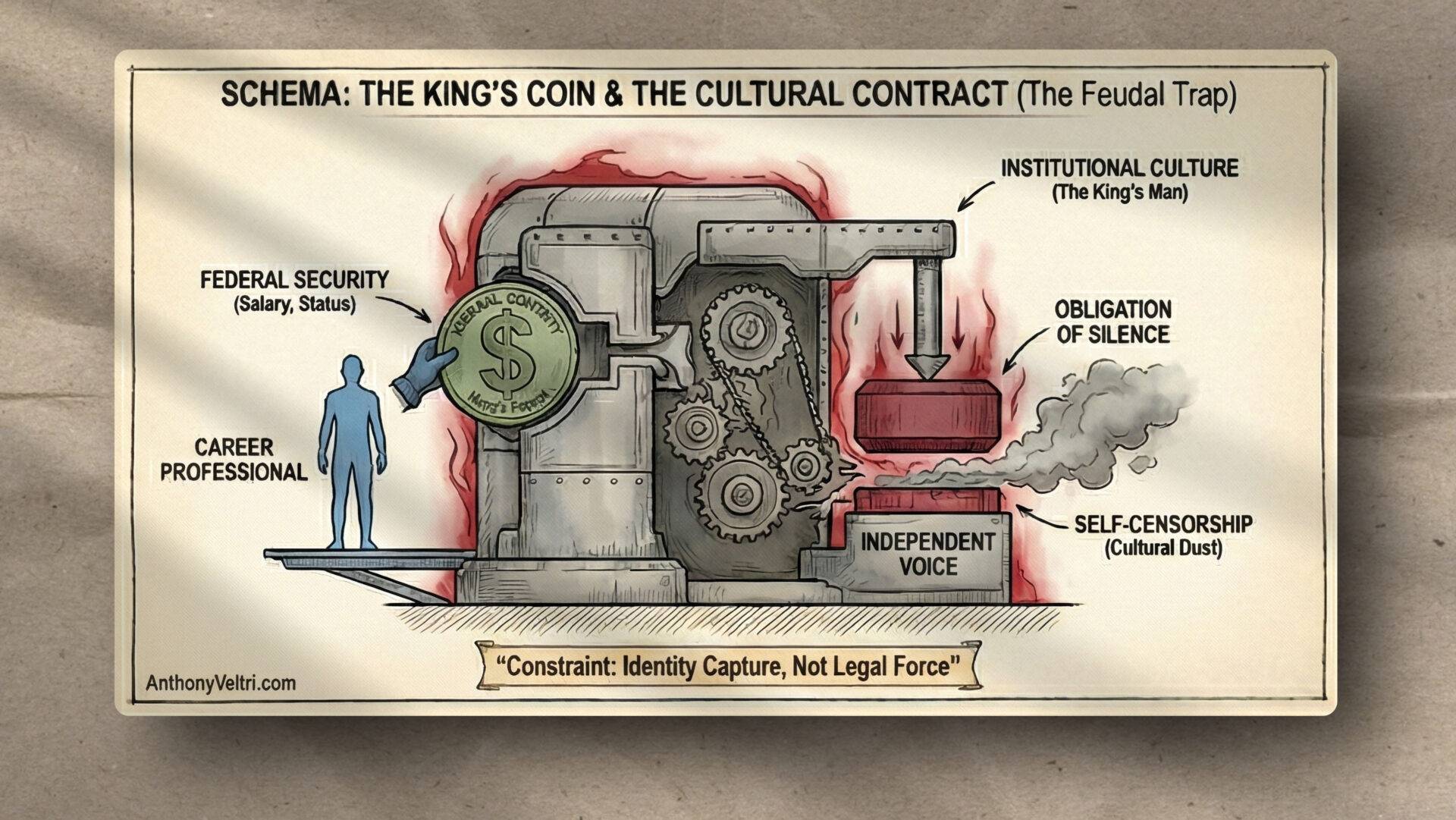

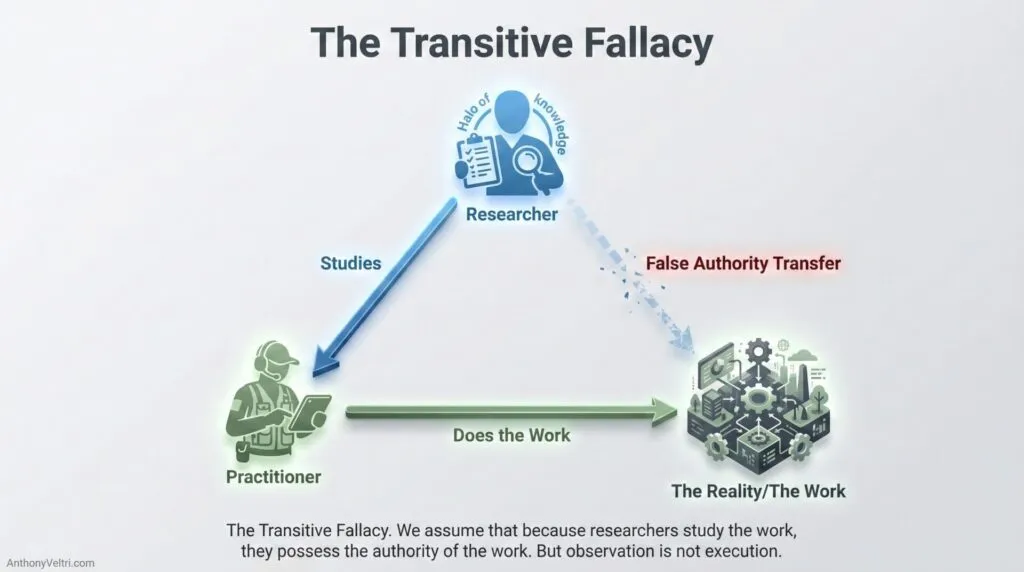

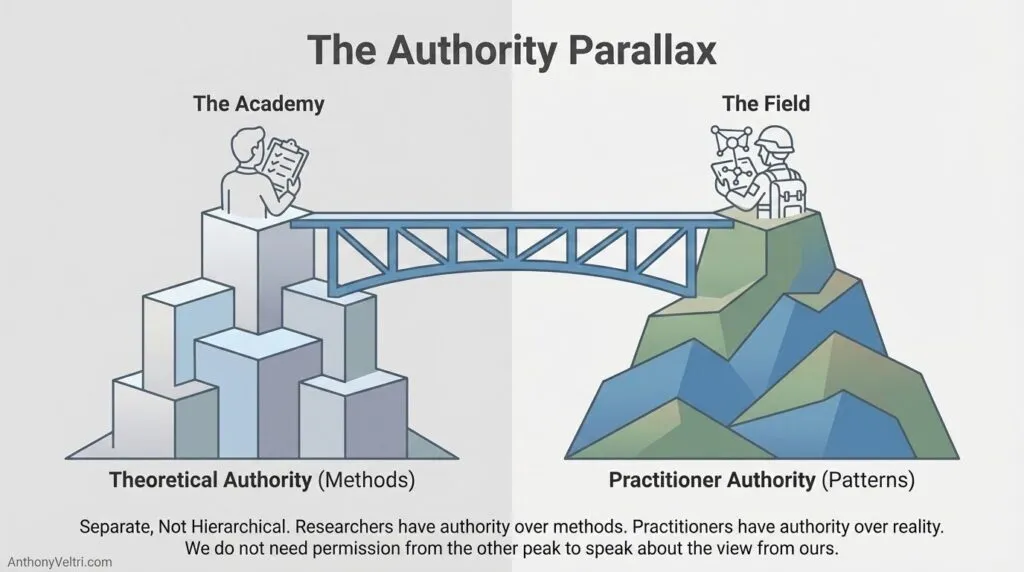

I believed in what I now call the transitive property of executive achievement: if researchers study practitioners or systems, and practitioners do the work on the systems, somehow researchers have more authority to speak about the work than the practitioners themselves.

This is logically incoherent, but socially powerful.

This wasn’t an accidental belief. It was a learned one. My early training was in academic science, where the hierarchy is explicit. I was the one in the field ground-truthing data, running the statistical models, and building the analysis tables, but the authority belonged to the Principal Investigator who formulated the hypothesis. I absorbed that worldview deeply. When I moved into operational leadership, I unconsciously carried that hierarchy with me. I mistakenly treated building and running critical systems as ‘data collection’ (necessary grunt work), but subordinate to the ‘real’ intellectual authority of the researchers observing us.

I deferred to people who studied disaster response, as if their analytical distance gave them clearer vision than my operational immersion. I assumed that academic frameworks and research methodologies somehow granted legitimacy that direct experience didn’t provide.

This belief is surprisingly common among practitioners. We keep quiet about what we know because we think we need permission from people who study what we do. We wait for validation from external authorities before we trust our own observations.

But it’s completely backwards.

What Researchers Have Authority Over

Researchers have legitimate authority over research methods, statistical analysis, literature synthesis, theoretical frameworks. Those are real domains of expertise that require years of training and represent genuine knowledge.

They don’t have authority over what it felt like to stand in the EOC during Hurricane Katrina. They don’t have authority over which integration patterns proved brittle under the operational pressure of high-consequence federal enterprise systems.. They don’t have authority over the decision altitude required for partnership coordination when multiple nations are trying to work together.

I do. Because I was there. I built the systems. I made the calls.

Researchers can study my work. They can analyze it, contextualize it, compare it to other cases. That’s valuable. But they can’t claim more legitimate knowledge of my operational experience than I have. The authority structures are separate, not hierarchical.

The Cost of Silence

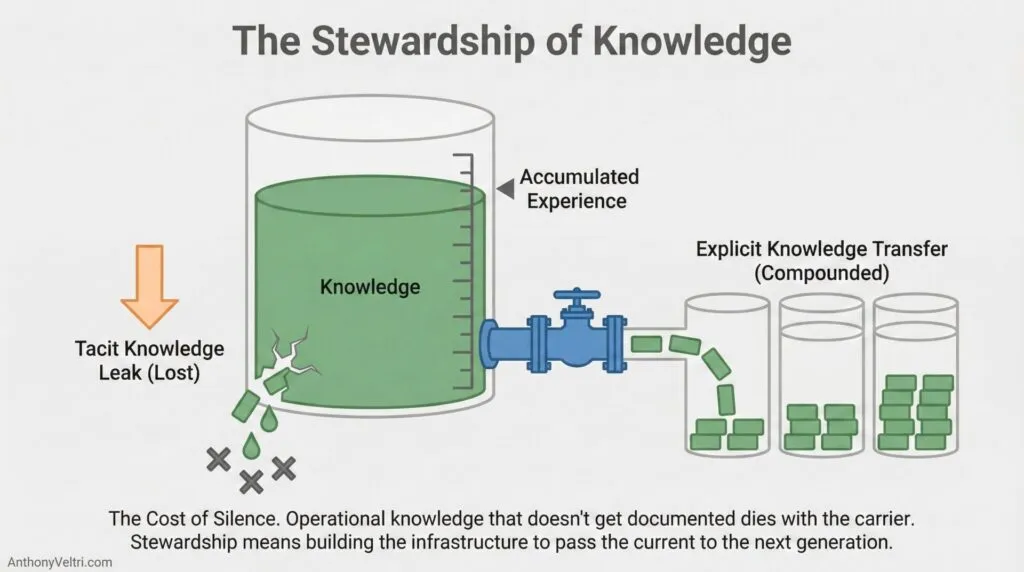

For 20 years, this knowledge existed only in my head and in the systems I built. Some of it got embedded in platforms that are still running. But the reasoning, the patterns, the hard-won understanding of what works and what fails, that stayed hidden.

This isn’t just personally limiting. It’s poor stewardship.

Operational knowledge that doesn’t get documented dies. It doesn’t transfer. It doesn’t compound. Each new practitioner has to learn the same lessons from scratch, often at high cost to the missions they serve.

I watched people make predictable mistakes because nobody had written down what we learned the last time. I saw organizations rebuild systems from first principles because the institutional knowledge had walked out the door. I experienced the same conversations about integration versus federation happening in 2024 that we were having in 2004, as if nothing had been learned in the intervening 20 years.

That’s what happens when practitioners keep quiet.

The Transition Point

What changed? Multiple things converged.

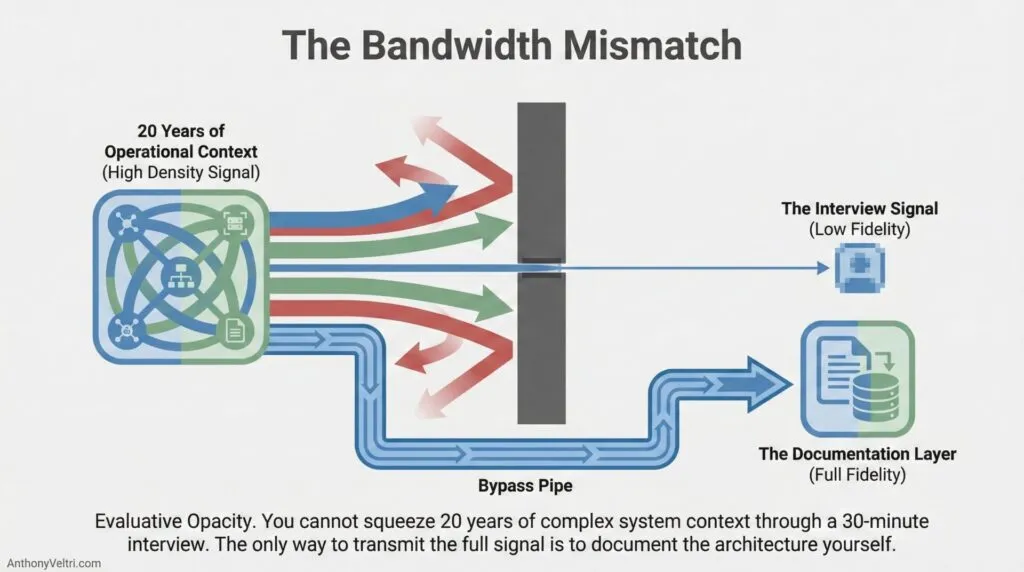

Career opportunities emerged that required demonstrating capabilities across domains that don’t naturally cluster in traditional career paths. But I ran into a structural problem: the “Bandwidth Bottleneck.”

Traditional hiring has low bandwidth (30 minutes). Your career has high data density (20 years). You needed a high-bandwidth channel (The Doctrine) to transmit the full signal.

When you try to shove high-density experience through a low-bandwidth channel, you end up “evaluatively opaque.” The signal gets compressed until it is unrecognizable.

I realized that if my preparation energy went entirely toward panel performance rather than comprehensive documentation, I would remain opaque regardless of my capability. The documentation work became essential not for one specific opportunity, but because it is the only way to actually map those domains and show how they connect.

The recent infrastructure sprint built the platform that finally made systematic documentation feasible. Without the visual system and the bidirectional references, this would still be too heavy a lift.

But most fundamentally: I finally recognized that practitioner authority is real and legitimate. I’m not overstepping by documenting what I know. I’m doing the stewardship work that operational knowledge requires.

What Gets Documented

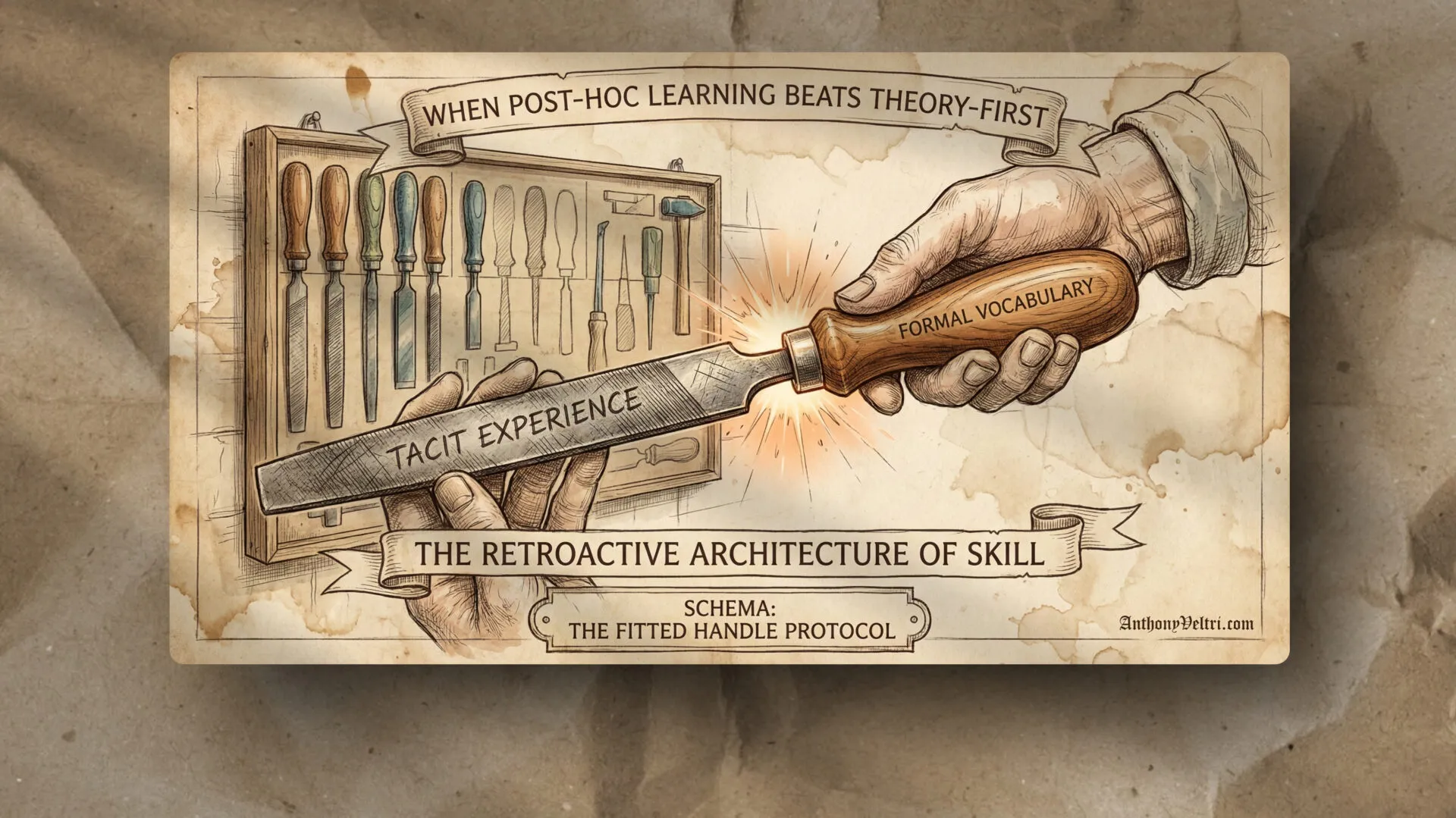

This isn’t about writing academic papers or pretending to be a researcher. It’s about documenting practitioner knowledge in practitioner terms:

Field patterns observed across multiple deployments. Design decisions that worked or failed under operational pressure. System architectures that proved resilient versus brittle. Integration strategies that enabled coordination without tight coupling. The actual mechanics of how operational systems function in crisis.

Loop closure as system infrastructure. The difference between stiff (brittle) and loose (resilient) coupling. Decision altitude frameworks.

This knowledge exists nowhere else. If I don’t document it, it’s lost.

The Stewardship Obligation

I’ve spent 20 years building systems for teams making high-consequence decisions. Those systems required deep understanding of how organizations function under pressure.

Good stewardship means I don’t let that understanding die with my career. I document it. I make it available. I give the person standing in the EOC twenty years from now something to build on, rather than forcing them to rediscover everything from scratch.

This is the same stewardship principle I apply to the farmhouse, to the land, and to the architecture that maintains stable services while enabling adaptive evolution.

Knowledge requires stewardship too.

The doctrine volumes, the annexes, the field guides, the systematic reference architecture, that’s not ego. That’s stewardship of knowledge that would otherwise be lost. It’s finally doing the documentation work I should have been doing all along.

Why Now Matters

The timing isn’t random. I’m 20+ years into a career that gives me enough pattern recognition to see what matters. I’m at a transition point where career opportunities make documentation necessary rather than optional. I have infrastructure that makes the work feasible.

And critically: I finally understand that I’m allowed. That practitioner authority is real. That documenting my operational knowledge isn’t presumptuous, it’s responsible.

I kept quiet for 20 years because I believed a false permission structure. I’m not keeping quiet anymore because I recognize that operational knowledge requires stewardship, and stewardship requires documentation.

The knowledge exists. The infrastructure exists. The authority is inherent in having done the work.

Now the documentation can finally happen.

Last Updated on January 9, 2026