Session Hijacking in 1999: What A URL Bug Taught Me About Trust Models

Or: Finding Security Holes The Hard Way Before We Called Them That

Act 1: The Takeover

In mid-1999, I took over an e-commerce business from a friend. He’d bought a bunch of inventory (crash pads and other gear for bouldering) and then got busy with his actual professional job. The pads were sitting in his space, not moving, and he needed them gone.

I was not yet 20 years old. I didn’t have a business plan. What I had was some climbing experience, my parents’ garage, and the realization that there was a real gap in the market.

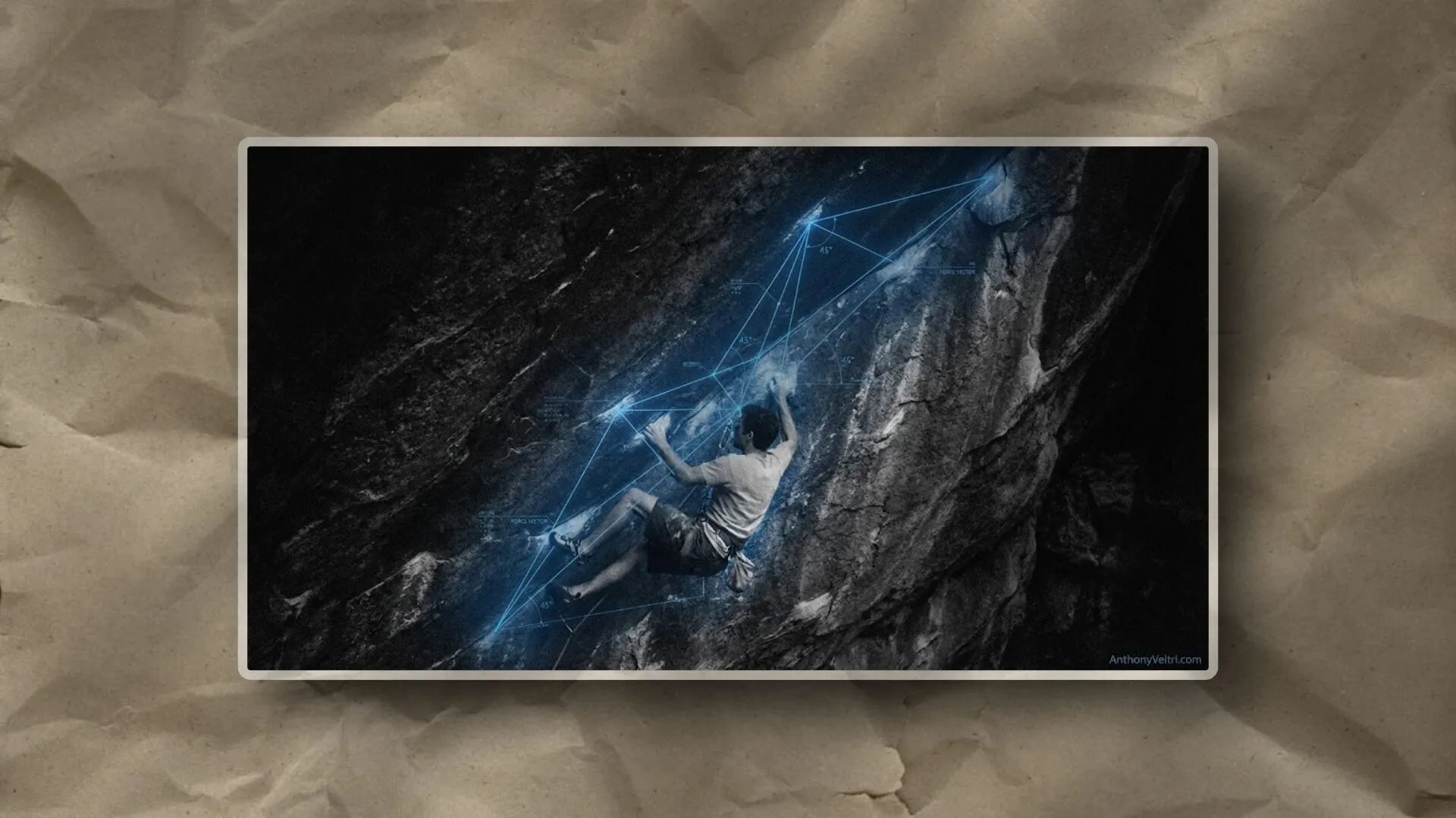

Let me explain crash pads for anyone who doesn’t climb. Bouldering is rock climbing close to the ground, no ropes. You’re practicing harder moves than you’d attempt on a rope, building muscle memory and problem-solving skills. The theory is that this rehearsal translates directly when you’re higher up with actual consequences. You’ve already done harder moves at ground level, so when you encounter an undercling in a dihedral corner 40 feet up, you aren’t thinking, you’re pattern matching. Your body recognizes the geometry and executes the solution before your conscious brain can argue about it.

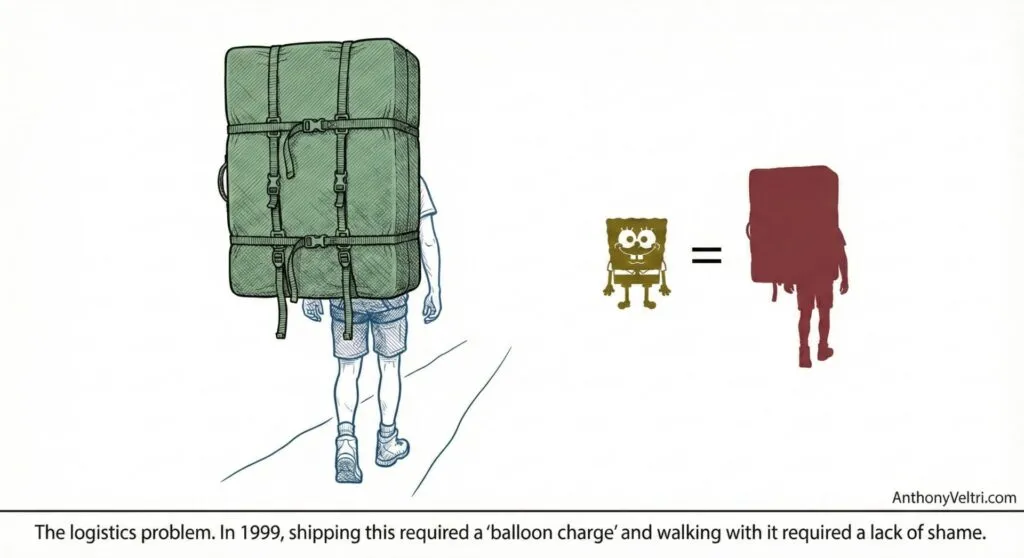

Crash pads are giant foam rectangles (usually about 4-5 feet by 3 feet by 4 inches thick, but sometimes much bigger) with a durable nylon shell and backpack straps. You carry them to the bouldering area, unfold them under the problem (the climb you are attempting) you’re working on, and they give you a somewhat softer landing when you fall. They don’t eliminate the risk, but they reduce it enough that you can attempt moves you’d never try without them.

When you wear one on your back, you present an almost perfect SpongeBob SquarePants silhouette. Especially back then. People would stare. “What the hell is that guy carrying?” And if you’re with a group of climbers (bouldering is social), you’d have a whole crew of SpongeBobs walking through suburban Boston neighborhoods to access bouldering spots that made you feel like you’d popped out of the city into nature.

The problem with crash pads in 1999 was that they took up tremendous floor space. They were challenging to store. They were bulky to ship. This was my first introduction to the USPS dimensional weight “balloon charge” where they charge by volume, not just weight.

It wasn’t just the walk of shame into the post office with these giant packages. We actually ended up shipping them in industrial-sized bags that looked like heavy black plastic trash bags. There was no scheduled pickup. There was no on-demand retrieval like there is with UPS today. You had to physically drag these things to the counter.

And the balloon charge was a game of roulette. The item was so close to the size limit that it depended entirely on who was working the counter. Sometimes the clerk would just wave it through. Other times, they would pull out the measuring tape, measure the girth, and hit me with the surcharge.

Most retailers at the time were drop-shipping, but not in the modern sense.

Here’s how it worked: You’d call the manufacturer. You probably knew the person on the other end of the phone. You’d say “please send a crash pad to this customer.” They might say “okay, we’re shipping next Thursday.” Or maybe “we’re not going to be able to ship any for two weeks.” Because while they would drop-ship, that wasn’t their primary focus. They wanted to move multiple pads at a time. That’s how their production system worked.

The value I could provide was speed. My parents’ garage became a very small, very dusty version of an Amazon warehouse. I could store enough crash pads to actually have inventory. And via USPS Priority Mail, I could ship one of these dimensional nightmares anywhere in the United States in a couple of days. That was tremendous convenience compared to the manufacturer lead time.

I remember sending pads to people on their climbing trips. Something had happened to theirs, or they’d forgotten it, or they realized mid-trip that they needed one. The appreciation was genuine. This wasn’t just commerce. This was enabling people to climb.

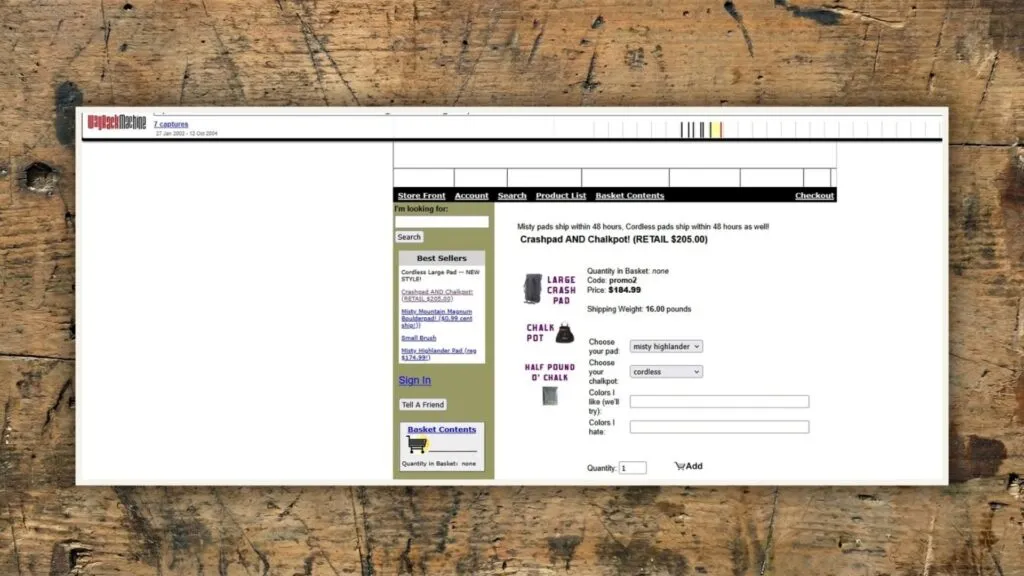

Digital archaeology: Recovering the site from the Wayback Machine proved that the value proposition wasn’t just in my head.

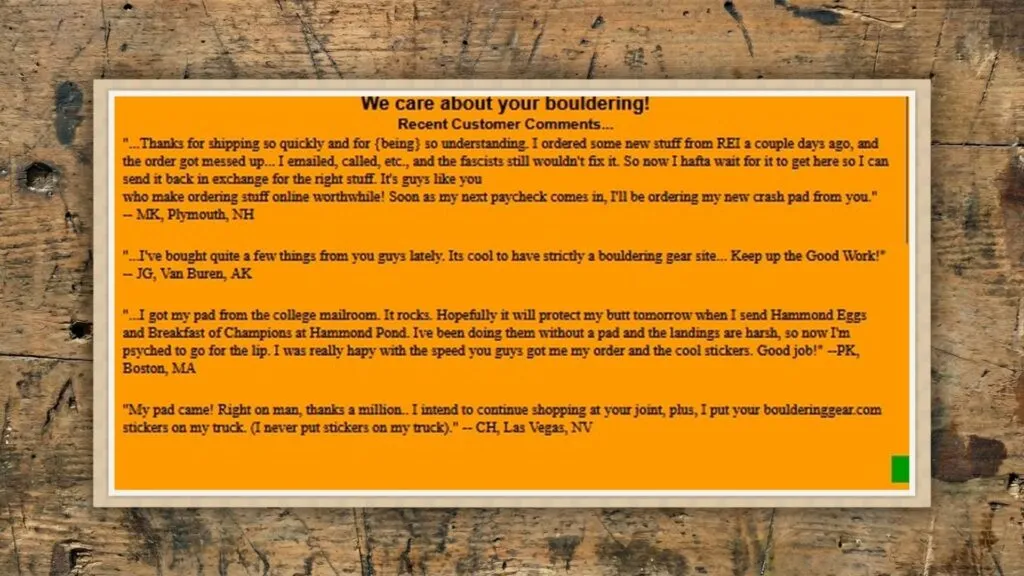

I recently went back and pulled the site up on the Wayback Machine. Reading the testimonials 25 years later was a shock. I had forgotten that people didn’t just like the gear (they liked the service).

One customer wrote from Plymouth, NH:

“I ordered some new stuff from REI a couple days ago, and the order got messed up… I emailed, called, etc., and the fascists still wouldn’t fix it… It’s guys like you who make ordering stuff online worthwhile!”

Another from Las Vegas:

“I intend to continue shopping at your joint, plus, I put your boulderinggear.com stickers on my truck. (I never put stickers on my truck).”

And a climber in Boston accessing the local crags:

“Hopefully it will protect my butt tomorrow when I send Hammond Eggs and Breakfast of Champions at Hammond Pond… I was really happy with the speed you guys got me my order.”

I called it Bouldering Gear.

Act 2: Infrastructure in 1999

If you wanted to sell things online in 1999, you built it yourself. Or more accurately, you found software that mostly worked and figured out how to make it actually work.

There was no Shopify. No “easy button” for e-commerce. Amazon existed but hadn’t yet become the everything store. If you wanted to sell specialty equipment to a niche community, you needed:

- A server (or hosting that gave you enough control)

- E-commerce software you could install

- An SSL certificate (expensive, manual installation, annual renewal)

- A way to process credit cards

- The technical knowledge to make all of this work together

I used Miva Merchant. It was one of the few platforms you could actually install and run without a development team. The software used a .mv extension (this was before they compiled it into .mvc). Being pre-compiled meant you could actually read and edit the source code, which would become important later.

SSL certificates were a real obstacle. Not just technically, but financially. You couldn’t just click a button and get HTTPS. This was before Let’s Encrypt (2015). This was probably before cPanel had automated certificate installation. You had to:

- Buy a certificate (likely from Thawte or Verisign)

- Figure out how to install it on your server

- Renew it every year

- Hope you did it correctly

The certificates cost real money. Probably $200-500 per year. That might not sound like much now, but for a garage operation run by someone under 20, it was another expense and another technical hurdle. And if something went wrong, finding someone who could troubleshoot these things was exceptionally expensive and difficult. Especially in a timely fashion.

Support for something like Thawte certificates was challenging for another reason: nobody knew how to pronounce “Thawte.” This sounds like a joke, but it’s a perfect example of tacit friction. If you can’t pronounce the name of the tool, you feel stupid asking for help. The inability to articulate the problem prevents the transfer of knowledge.

I tried multiple approaches to finding customers. Took out traditional print ads in climbing magazines (my first introduction to four-color separation process and very expensive advertising rates). Tried web ads. But ultimately, word of mouth and organic search were what worked. Climbers are a tight community. If you solve a real problem, people talk.

Miva seemed like a giant at the time. Professional. Established. They even sent me a Carhartt Detroit jacket with the Miva logo on it. I still have it somewhere. To a 19-year-old running an e-commerce operation out of his parents’ garage, this felt like validation. Like I was part of something real.

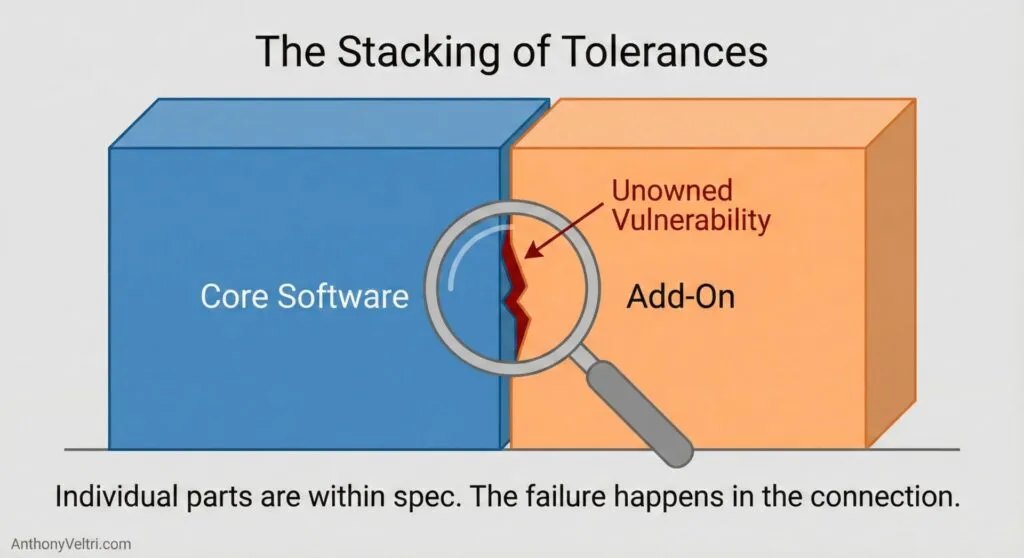

But the Miva ecosystem had a strange characteristic that I didn’t fully appreciate until later. There was a marketplace called the Miva Emporium where developers sold add-ons. Email templates. Checkout modifications. Inventory management tools. Each add-on solved a specific problem, but created a “stacking of tolerances” problem.

In engineering, a “stacking of tolerances” is where individual parts are within spec, but when combined, the small variances add up to create a failure. The core software might work fine. The add-on might work fine in isolation. But together, they could create gaps that nobody owned. The core developers would say “that’s the add-on’s problem.” The add-on developer would say “the core software shouldn’t allow that.”

And you, the person running the store, were stuck figuring out where the gap was. I was about to learn this the hard way.

Act 3: “Hey Bro, My Cart Keeps Getting Replaced”

A customer contacted me. Not panicked. Not threatening legal action. Just confused.

“Hey bro, my cart keeps getting replaced with some other dude’s. Can I just call you and order directly?”

This was a different era. There were no data breach notification laws. No disaster management playbook for when customer information gets exposed. No PR crisis to manage. Just a weird bug that was annoying a customer.

My first thought was that I’d screwed up the database somehow. Mixed up records. But when I started troubleshooting, the pattern didn’t make sense for a database issue.

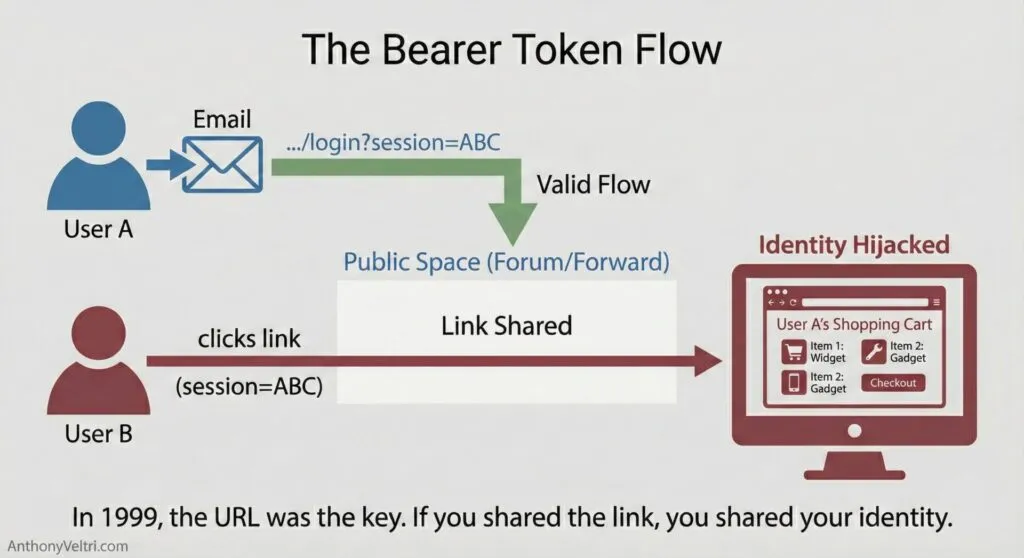

Then I looked at the URLs involved and understood what was happening. Miva Merchant in that era tracked sessions with IDs in the URL:

https://boulderinggear.com/checkout?session=abc123xyzThe session ID was right there. Visible. Copy-paste-able. At the time, this seemed fine. Convenient, even. The URL contained all the state. You could bookmark your shopping cart. You could email someone a link to what you were looking at.

But here’s what was happening: the account confirmation email that Miva sent when someone created an account had a login link in it. And that login link included a session ID.

If someone clicked that link from the email, they’d get logged in. But if someone else somehow got that URL (maybe it was forwarded, maybe it was shared on a forum, maybe it was cached somewhere), they’d hijack that session.

Click the link = become that user. See their cart. See their shipping address.

The issue wasn’t affecting everyone who visited the site. That’s probably why it didn’t get picked up earlier. It was specifically the account confirmation email flow. Not the main shopping flow.

I reported it to Miva. Their response came about a week later. Maybe a little more. Something like “we’ll look into it.” There might have been an immediate auto-response confirming receipt, but there was no urgency. No emergency patch. No “take your site down until we fix this.”

Because in 1999, this was just a bug. Not a security incident. Not a breach. Just something weird that needed fixing when they got around to it. I couldn’t wait for them to fix it. Customers were getting confused. So I troubleshot it myself.

The email template was an add-on from the Miva Emporium. Because Miva was pre-compiled (.mv, not .mvc), I could actually read the source code. And I could edit it.

I found the line that generated the login link with the session ID embedded. I’m not sure I was sophisticated enough at the time to surgically remove just the session variable from the URL parameter. So I probably just removed the whole line. The entire login link.

The behavior stopped.

I made it a quiet fix. I didn’t send an email to all customers explaining what happened and what I’d done. This was a different communication culture. As long as nobody’s credit card got mischarged, people would have thought “why are you bothering me to tell me you fixed your website?”

But I learned some things:

- I learned to look at log files. They sucked back then. They suck now, but they sucked a lot more back then. But they showed me patterns I wouldn’t have seen otherwise.

- I learned to watch Linux processes in real time. Using

topandpsto see what was actually running, what was consuming resources, what was hanging. This sucks as bad now as it did then. Some things never change. But when something is broken and you can’t replicate it consistently, watching processes in real time sometimes shows you what log files can’t. - I learned about the “stacking of tolerances” problem. The core Miva software probably shouldn’t have allowed session IDs in URLs that way. But it did. The email add-on probably shouldn’t have embedded session IDs in login links. But it did. Together, they created a gap that nobody wanted to own. The core developers would say “that’s the add-on’s fault.” The add-on developer would say “the core software allows it, so it’s valid.” And I was stuck in the middle, figuring out where the break actually was.

- I learned about trust boundaries, though I didn’t have that vocabulary yet. Client-side state can’t be trusted. Session IDs in URLs are tokens that can be copied, shared, cached, and replayed. You can’t assume that the person presenting a session ID is the person it was issued to.

Act 4: What I Learned (That I Didn’t Know I Was Learning)

I ran Bouldering Gear from 1999 to 2003. Four years of shipping crash pads, troubleshooting Miva quirks, learning about USPS dimensional weight charges, and occasionally fixing security issues I didn’t have the vocabulary to properly name.

At the time, it was just “running an e-commerce business.” Solving problems as they came up. Making it work with the tools available.

But the patterns I learned then shaped how I think about systems now:

1. Session management matters. Tokens have to be protected. Client-side state can’t be trusted. The person presenting a credential might not be the person it was issued to.

2. Interfaces between vendors create gaps nobody owns. Core software plus add-ons plus marketplace ecosystem equals stacking of tolerances. The break happens at the boundary, and everyone points at someone else.

3. Test everything, including the things that seem peripheral. The main shopping flow was fine. The bug was in the account confirmation email. Not where you’d look first.

4. Security through obscurity isn’t security. The session hijacking issue only affected people who clicked email links. Seemed like a minor edge case. But edge cases are where vulnerabilities hide.

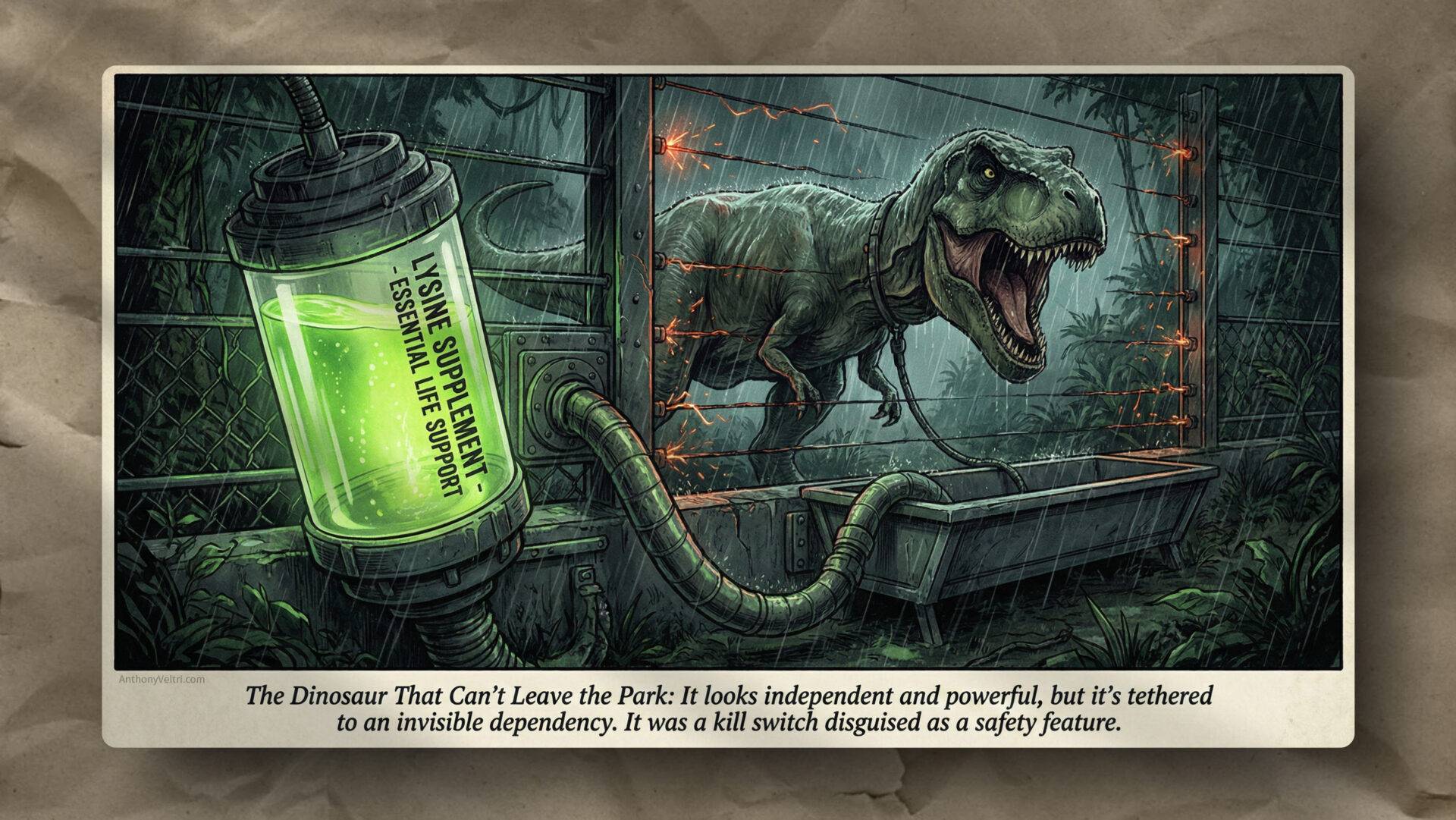

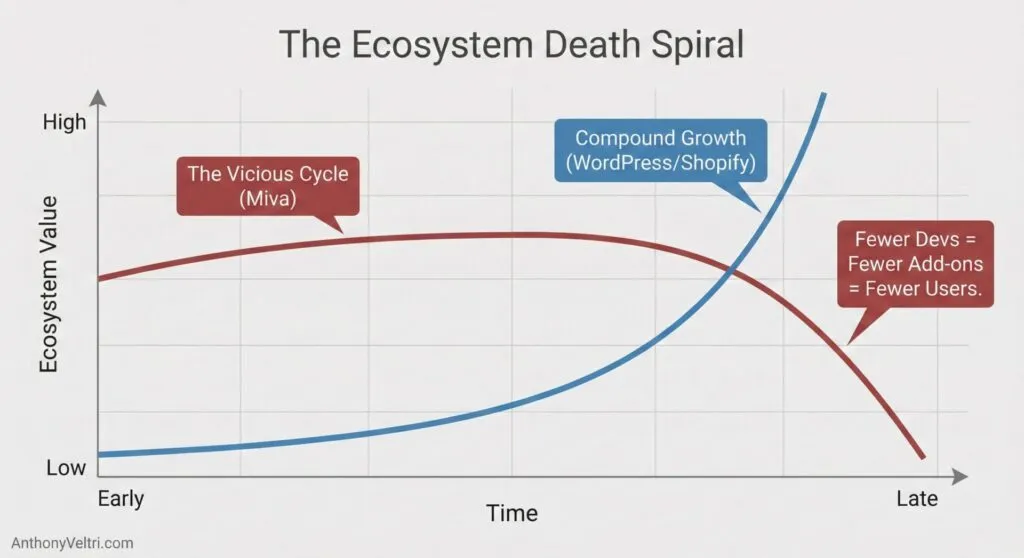

5. Infrastructure you depend on can disappear. Miva seemed like a giant to me. Professional. Established. That Carhartt jacket meant something.

But look at what happened:

Miva launched as HTMLScript in 1995, renamed to Miva in 1997, and quickly gained market share in the late 1990s by licensing to hosting companies. They seemed dominant. In 2012, they were still named one of the top 10 e-commerce technology companies.

Then the erosion started. The dot-com bust hit them hard. They sold to FindWhat.com (a pay-per-click ad network) in 2004. FindWhat.com renamed itself Miva in 2005. The shopping cart business got divested to private investors in 2007. Multiple pivots. Name changes. Attempts to adapt to SaaS models.

Today? Miva has approximately 1,490 live stores. Market share of 0.06%. Compare that to WooCommerce (70%) or Shopify (17%). The stores that run on Miva are declining 6% year-over-year.

It’s not that Miva failed completely. They still exist. They’ve pivoted multiple times. They offer a SaaS platform now. The software probably works fine for the stores still running it.

But ecosystem size matters. In the late 1990s, the Miva Emporium marketplace was where developers built add-ons. Email templates. Checkout modifications. Inventory tools. There was a community.

Now? WordPress has over 60,000 plugins. Shopify has 8,000+ apps. Miva has a handful of add-ons. The ecosystem compound effect works in reverse. Fewer users means fewer developers. Fewer developers means fewer add-ons. Fewer add-ons means harder to justify choosing the platform. Which means fewer users.

It’s the same pattern as WordPress versus Drupal. Both work. Drupal might even be better for specific use cases (the US government prefers it for security reasons, though I’m sure they have their rationale). But WordPress powers 43% of all websites. Drupal is around 2%. Unless you have a very particular reason to use Drupal, you don’t want to hitch your wagon to the smaller ecosystem.

When you’re building on infrastructure, you’re betting on ecosystem size as much as technical capability.

Funny sidebar: I looked up vintage Carhartt Detroit jacket prices recently. Turns out that jacket might be the most valuable thing I got from Miva. And it continues to hold value today, unlike the platform it was promoting.

This isn’t unique to technology platforms. The supermarket I thought would always be there closed. Eastern Mountain Sports, where I bought climbing gear, went bankrupt. Even local anchors disappear. Nothing is permanent. But with technology platforms specifically, the ecosystem effect accelerates the decline. It’s not just that Miva got smaller. It’s that getting smaller made them less valuable, which made them get smaller faster.

Years later, when I worked on Zero Trust architectures for federal systems, I didn’t consciously think back to the session hijacking bug. But the patterns were there.

The session ID was a “bearer token.” Whoever held the ticket got the ride. Zero Trust is simply the realization that tickets can be stolen, so we check ID at the gate even if you have a ticket.

I didn’t connect them until right now, writing this down.

Coda: Why This Story Matters Now

I found screenshots of the BoulderingGear.com website on the Wayback Machine while writing this. The testimonials are still there. Customer feedback about beating REI on service. Someone saying they put my stickers on their truck even though “I never put stickers on my truck.” The “We care about your bouldering” header that made it clear this wasn’t just transactions.

Without the Wayback Machine, even the website would be gone. The only evidence it existed would be that Carhartt jacket and my increasingly fuzzy memories of troubleshooting session hijacking bugs.

This is the pattern that keeps showing up: the things that shape how we think get lost unless we deliberately preserve them.

The scythe sharpening knowledge disappeared because everyone who used scythes knew how, so documenting it felt unnecessary. The pyramid construction techniques are gone because they were common knowledge to the builders. And my 1999 e-commerce security lessons were fading because they felt routine at the time.

But those lessons weren’t routine. They were foundational. Session management. Trust boundaries. Client-side tokens. Vendor integration gaps. Ecosystem dependency. The patterns I learned troubleshooting a Miva Merchant bug in my parents’ garage shaped how I approached zero trust architectures in federal systems 15 years later.

I just didn’t connect them until I sat down to document it.

This is why I’ve been building comprehensive documentation of patterns I’ve used for 20 years. Not because I think they’re special. Not because I’m trying to impress anyone. But because I’ve learned that the capability we take for granted (the stuff that feels too obvious to document) is exactly what disappears.

And when it disappears, we lose more than just the knowledge. We lose the lineage. The connection between where we’ve been and where we are. The foundation that explains why we make the decisions we make.

Documentation isn’t just about preserving what you know. It’s about preserving how you learned it, why it matters, and where it connects to everything else you’ve done.

The solo integrated operator problem is that all of this stays locked in your head. The velocity is extreme. The capability is real. But without documentation, even you forget where it came from.

So now this story exists. The session hijacking bug. The Miva Emporium stacking of tolerances. The Thawte pronunciation problem. The customer who broke his own rule about stickers. The patterns that shaped how I think about trust.

It’s documented. Which means it can transfer. Which means it won’t disappear.

That’s the point of all of this.

Last Updated on February 14, 2026