Why architects must preserve autonomy while achieving alignment #

This page is a Doctrine Guide. It shows how to apply one principle from the Doctrine in real systems and real constraints. Use it as a reference when you are making decisions, designing workflows, or repairing things that broke under pressure.

This guide explains why federation over full integration keeps mission networks flexible, politically viable, and fast to adapt without forcing every partner into one rigid stack.

Use this guide when: deciding between unified platform vs. federated approach

You’ll learn: why federation scales, when integration fails, how to design for diversity, and when integration can be best.

Most complex mission networks fail because architects demand uniformity in environments where uniformity doesn’t exist.

Partners arrive with different systems, budgets, politics, and technical maturity. When you force them into one stack, participation shrinks. When you preserve their autonomy while creating alignment, capability grows.

This is why federation works where integration fails.

A Quick Note on Terminology: “integration” vs “federation” (and what federation gets called elsewhere) #

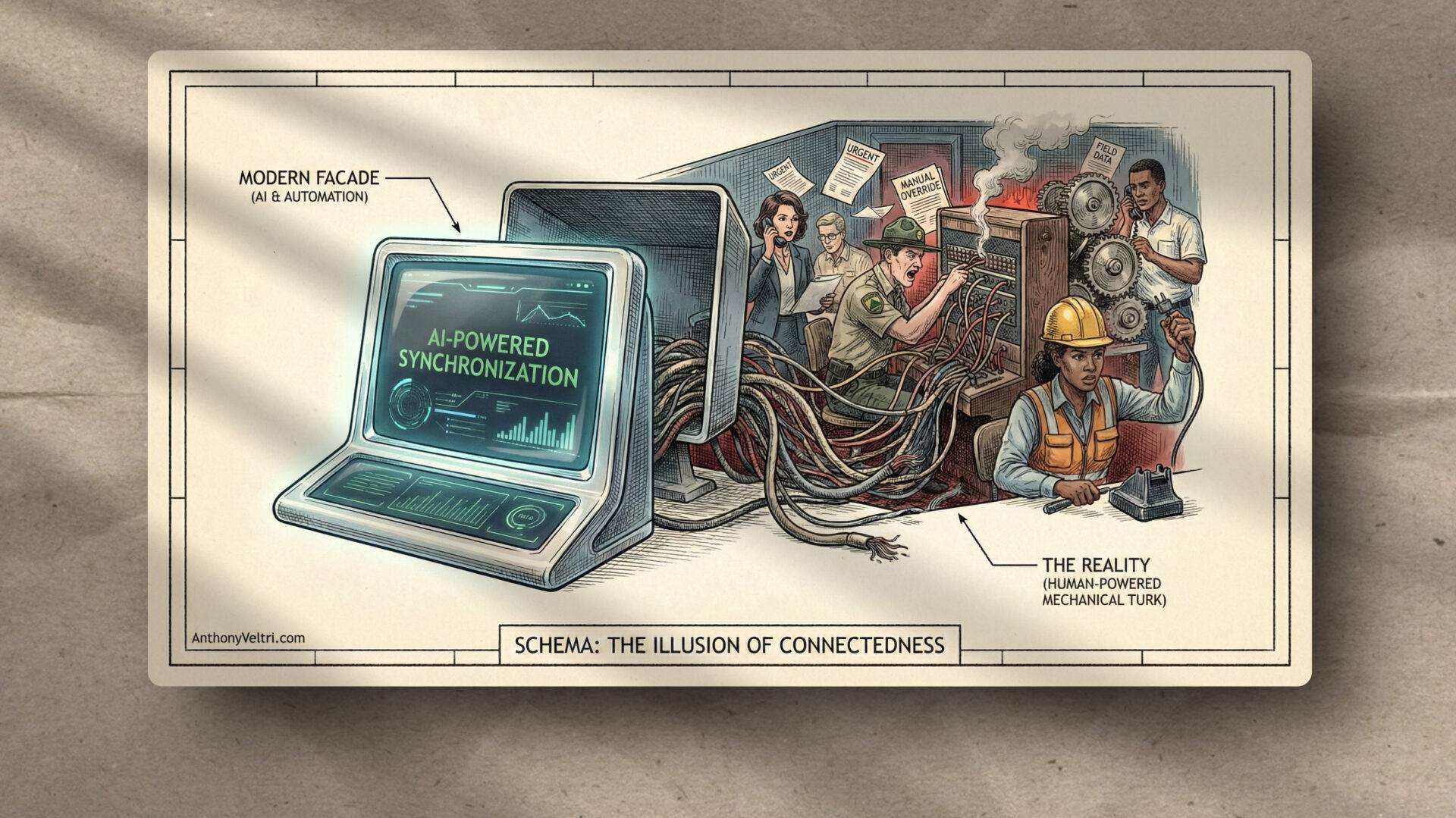

These words are overloaded. People often say “integration” when they really mean “connectors” (toolchain integration), and they often avoid the word “federation” entirely and use other labels depending on the community.

When people ask “does it integrate,” they often mean connector integration. In this Doctrine, integration is usually governance integration: shared (or forced) rules, shared schema, shared controls, and shared decision rights that create one operating system for the network.

What is meant by integration (in this doctrine) #

Integration is a unified platform move: one system, one schema, one update model, one governance path. It is clean, but it is also tight coupling: changes propagate, outages propagate, and the center becomes the bottleneck.

What is meant by federation #

Federation is a boundary and interface move: many systems remain in place, and you build the harmonization, caching, normalization, crosswalks, and translation needed to produce a shared operational picture. Output can be centralized, but ownership stays local.

Quick discriminator: are we talking about connectors or architecture? #

- Connector integration (toolchain integration): Systems can pass data, trigger workflows, and “talk” via APIs, ETL, automations, and connectors. This can exist even when everyone stays autonomous. “Does this integrate with Jira, ServiceNow, Salesforce, Google Docs, Zapier, Power BI?”

This is about APIs, automations, and data movement. - Governance/Operating Model integration (organizational or architectural integration): Teams agree (or are forced) into shared rules: common schema, common definitions, common controls, common workflow, shared change management, shared accountability, and usually a shared operating cadence. “Are we forcing standardization into one stack, or preserving autonomy and coordinating through interfaces?” This is about authority, governance, and who pays coordination costs.

What federation might be called depending on the context #

Different groups use different labels for the same underlying move: preserve local autonomy, coordinate through interfaces.

- Interoperability / useful interoperability: emphasis on “works together” without forcing uniformity.

- Loose coupling with strong interfaces: architecture language for boundary-first coordination.

- Mediation layer / translation layer / harmonization layer: data and systems language for the middle that does crosswalks and normalization.

- Hub-and-spoke exchange / brokered exchange: a central broker enables coordination without migrating everyone to one tool (ownership stays distributed).

- Ecosystem model / network-of-networks / system-of-systems: mission and coalition language when the reality is heterogeneous participants and voluntary alignment.

- Federated model: identity and governance communities use this when authority is distributed and agreement is interface-based, not platform-based.

One line decision rule #

If you can’t compel compliance, federation is not a style choice. It is the only model that can scale participation without pretending the world is uniform.

The world is not uniform #

Mission environments are not controlled factories.

Partners do not share the same systems, budgets, politics, authorities, maturity levels, or technical stacks.

If you demand uniformity, you shrink participation.

If you preserve autonomy while creating alignment, you grow capability.

This is the foundation of federation.

Lived Example: What hurricane season taught me about federation #

During one hurricane cycle at DHS, we had partners with:

- near real-time cloud GIS

- on premise ArcGIS Servers held together with tape

- CSV files exported from legacy databases

- static KMLs uploaded only when staff were available

- password protected endpoints that expired during the activation

- one partner who could only send updates by emailing them to a duty analyst (yes, really)

If we had required integration into a single platform, half of these partners would have been excluded or would have needed money and time they did not have.

Instead we built a federation layer:

- it accepted many formats

- it accepted different refresh rates

- it accepted different authentication models

- it accepted the reality of each partner’s world

- it accepted the politics of sovereignty, budget, and staffing

The result was not a perfectly clean dataset.

It was a more complete and inclusive operational picture.

That is the power of federation.

Business Terms: The case for federation #

Federation means:

- partners keep their autonomy

- systems stay where they are

- participation is easier

- trust increases because no one is coerced

- the shared picture grows as more people contribute

Integration means:

- replacing working tools

- high cost to change

- long approval cycles

- political resistance

- reduced participation

- one central system becomes a bottleneck

Federation accepts that partners differ.

Integration pretends they do not (and then wonders why partners resist).

System Terms: What federation actually is #

Federation is a technical topology:

- many systems feeding into a shared harmonization layer

- loose coupling

- asynchronous updates

- schema variation resolved at the edge

- failure isolated to local nodes

- harmonization, caching, and normalization centralizing output, not ownership

Integration is:

- one system

- one schema

- one update model

- one release cadence

- one failure domain

- one bottleneck

- tight coupling

Federation scales.

Integration slows down as partners increase.

Why Integration Fails in Mission Environments #

Business perspective #

Integration fails because it requires partners to:

- abandon tools they rely on

- secure funding they do not have

- reorganize workflows

- train staff on brand new systems

- commit to timelines they cannot control

- accept governance they did not choose

- justify changes to their own chain of command

Most mission partners do not have the authority or capacity to standardize around one tool.

Integration reduces participation.

System perspective #

Integration fails because:

- tight coupling increases fragility

- a schema change breaks the entire chain

- updates require synchronized releases

- outages propagate

- performance requirements become impossible to satisfy

- version control becomes politically sensitive

- migration projects stall

- one central team becomes overwhelmed

Integration reduces resilience.

Why Federation Succeeds #

Business perspective #

Federation works because:

- partners contribute what they can, when they can

- barriers to entry are low

- sovereignty is respected

- budgets are preserved

- adoption is friction free

- the operational picture grows with each contributor

- participation scales with trust

Federation increases collaboration.

System perspective #

Federation works because:

- loose coupling isolates failures

- asynchronous updates prevent blocking

- harmonization rules absorb variation

- caching covers gaps

- partner autonomy keeps systems robust

- schemas evolve independently

- governance supports growth, not restriction

Federation increases resilience.

Business Example: What DHS learned #

At DHS we onboarded partners who were on modern cloud environments and partners who were on legacy stacks that could barely publish a map. Some could refresh every few minutes; others once a day. If we had forced integration, the operational picture would have shrunk. Instead, federation allowed each partner to contribute at their level. The picture grew because we accepted the reality of their constraints.

System Example: What iCAV proved #

In iCAV we built a federation layer capable of ingesting ESRI services, CSVs, static KMLs, secured endpoints, and human uploads. We did not require partners to adopt the same stack. We harmonized, normalized, cached, and presented it in a unified viewer. Partners stayed autonomous. The mission picture stayed alive even when individual feeds dropped (which they did, frequently).

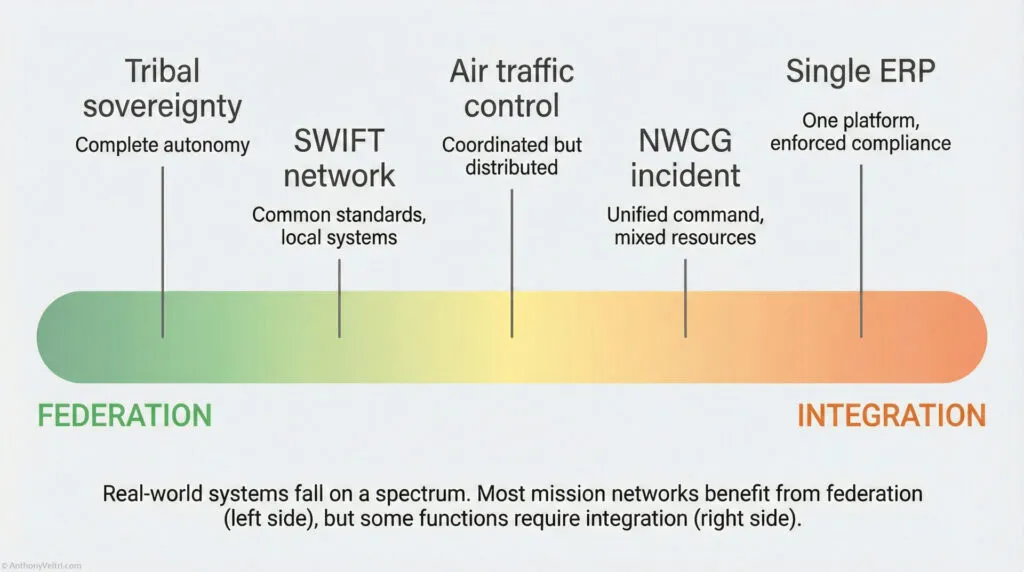

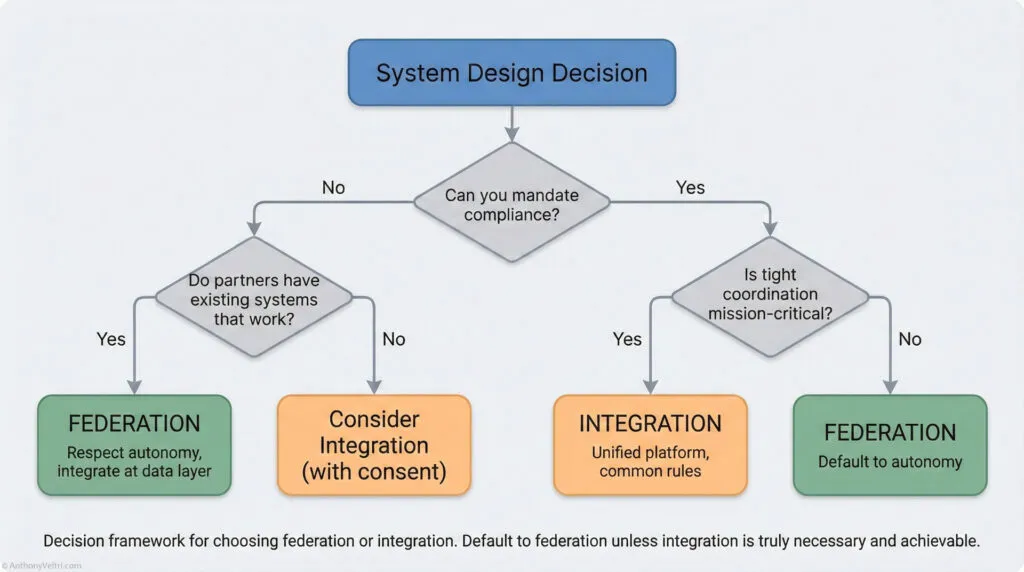

When To Choose Each Approach #

Choose Federation when:

- Partners have different technical maturity levels

- You don’t control their budgets or governance

- Political sovereignty matters (multi-agency, multinational, coalition environments)

- Participation is more valuable than uniformity

- The environment changes faster than you can standardize

- Partners need to maintain their existing workflows

- You expect the number of partners to grow or change over time

Choose Integration when:

- You control all partners and their budgets

- Uniformity is legally or operationally required (for instance, a single agency’s internal systems where policy mandates one stack)

- The cost of variation exceeds the cost of migration

- Partners agree to centralized governance

- The scope is narrow and the stakes are very high

- The number of partners is bounded and unlikely to expand significantly (like NWCG, where tight integration on doctrine and standards works because membership is limited and the operational culture is shared)

In complex mission environments, federation is usually the only viable approach because you rarely control all the variables integration requires. And even when integration works today, ask yourself: what happens if we need to add ten more partners next year?

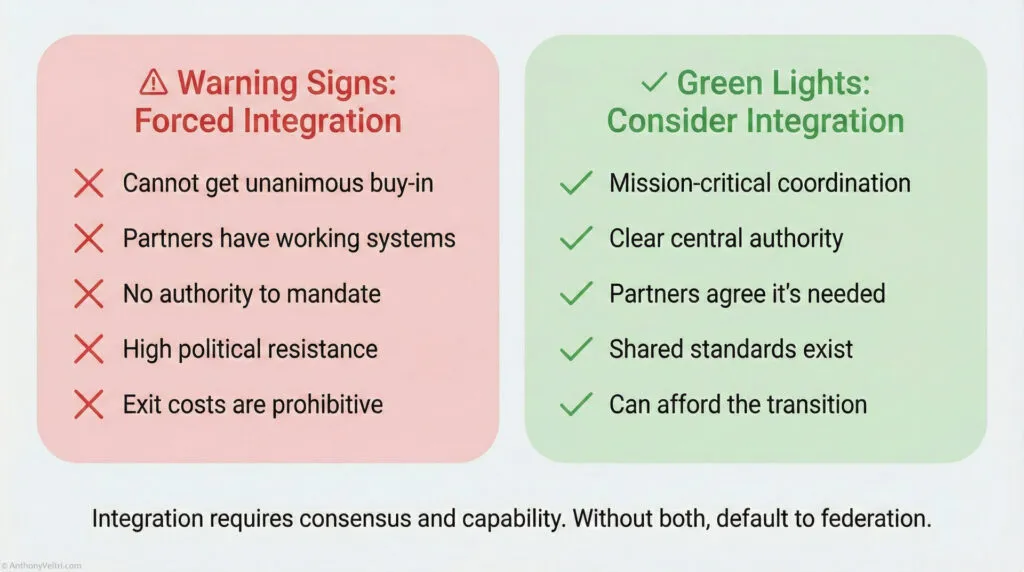

Red Flags That Integration Won’t Work #

You need federation, not integration, if you hear these phrases:

- “We can’t get budget approval for a new system”

- “Our IT security won’t allow that”

- “We don’t have staff to migrate”

- “Our leadership won’t agree to that governance model”

- “We’re using a system that’s end-of-life but still required”

- “We can only contribute when someone manually exports the data”

- “Our partners are in different countries with different policies”

- “We might need to add more partners later, but we’re not sure who yet”

- “Each organization has its own compliance requirements”

- “The approval process would take longer than the mission window”

If you hear three or more of these, federation is your only viable path.

These aren’t excuses. They’re constraints. Integration demands control you don’t have.

Vocabulary Crosswalk: What Federation And Integration Are Called In Different Communities #

You might not hear the words “federation” and “integration” depending on where you sit in the organization or what community you come from. Here’s what these patterns are called in different contexts:

If you’ve heard these terms, you’re talking about Federation: #

- Sovereignty (diplomatic, multinational environments)

- Distributed architecture (enterprise IT)

- Loose coupling (software engineering)

- Best-of-breed (enterprise software selection)

- Federated data sources (GIS and geospatial)

- Interoperability (defense and coalition operations)

- Data mesh (modern data architecture)

- Plug-and-play (product and systems design)

If you’ve heard these terms, you’re talking about Integration: #

- Single source of truth (enterprise IT, data governance)

- Tight coupling (software engineering)

- Monolithic architecture (software design)

- Enterprise-wide platform (IT strategy)

- Standardization (policy and compliance)

- Unified system (program management)

- One version of the truth (executive briefings)

The words change depending on whether you’re a technician, a manager, a leader, or come from an academic background. But the underlying tension is the same: do you force everyone into one system, or do you let many systems contribute to one picture?

Note: Once you’ve decided on federation or integration, you’ll need to think about how data gets harmonized, what schemas look like, and how vocabulary gets mapped across partners. For that, see Annex J: Data Modeling and Vocabulary Crosswalks in Federated Systems.

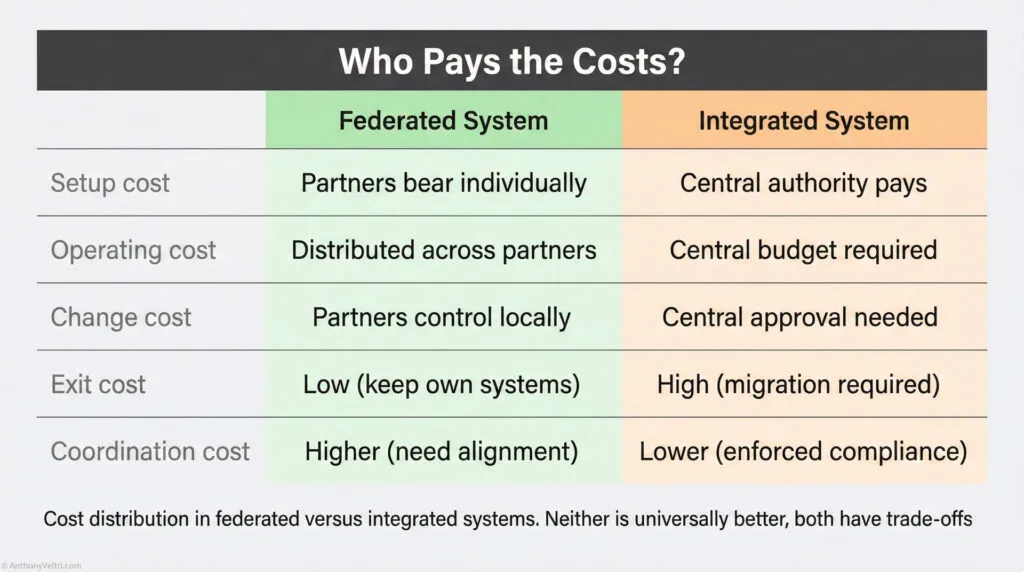

Who Pays The Cost #

Integration makes partners pay the cost of participation.

If you want to join an integrated system, you must:

- Adopt the required technology stack

- Meet the governance standards

- Fund the migration

- Train your staff

- Maintain compliance

This works when the mission justifies that cost. Air traffic control is a good example: the FAA maintains tight integration because lives depend on split-second coordination, and the government invests enormous resources to maintain that control. Partners (airlines, airports) must comply with the system’s standards or they can’t operate. Financial clearing systems like SWIFT work the same way: banks pay the cost of compliance because standardized message formats are required for money movement to work at scale. Similarly, classified military networks require tight integration because security requirements justify the cost of excluding partners who can’t meet the bar.

Federation makes the steward pay the cost of inclusion.

If you build a federated system, you must:

- Build and maintain the harmonization layer

- Accept multiple formats and refresh rates

- Resolve schema conflicts

- Cache and normalize

- Support partners at different maturity levels

The federation steward invests heavily in infrastructure so that others can plug in with what they have. A smaller country with a smaller budget can participate without ponying up to match your stack. They bring what they can. You harmonize it.

The trade-off is strategic:

- Integration: High barrier to entry, tight control, works when you can afford to exclude partners who can’t meet your standards

- Federation: Low barrier to entry, loose control, works when you need broad participation more than you need uniformity

In mission environments where you need coalition partners, allied nations, or multi-agency collaboration, federation is often the only affordable model. The alternative is excluding partners who could contribute but can’t afford your stack.

Architect Level Principle #

As an architect, I design federated systems because they scale with diversity.

Integration only works when you control every partner.

Federation works when you do not.

This is why in multinational and multi agency environments, federation is the only workable model.

Note: As with all complex systems, we must observe nuance. There are certain circumstances where integration within federation provides unique and powerful benefits if the scope is very focused and the consequences are very high. Read about that here

In Summary #

Integration optimizes for control. Federation optimizes for participation.

In complex mission environments where you don’t control budgets, governance, or political sovereignty, federation is the only architecture that survives contact with reality when partners or conditions change.

Integration can work in stable, controlled environments. But mission environments are rarely stable or fully controlled. New partners get added. Budgets shift. Policies evolve. Threats change faster than procurement cycles.

The question isn’t whether federation is better. The question is whether your environment will stay stable enough for integration to keep working. In most mission networks, it won’t.

If you’re trying to get everyone to live in one system, you’re designing for a world that doesn’t exist. If you’re building a system that accepts the world as it is, you’re designing for the real world.

Cross Links to Other Principles #

This principle is tightly connected to:

- Useful interoperability

- Interfaces and ownership

- Resilience as emergent

- Degraded operations

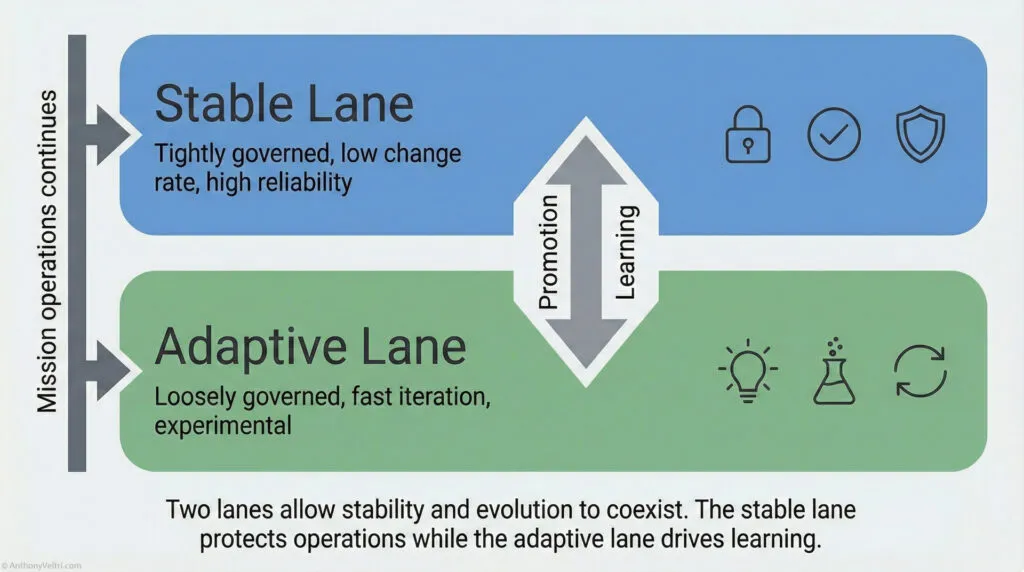

- Two-lane systems

- Decision drag (because forced integration creates infinite drag)

- Portfolio thinking (because federation optimizes for impact, not uniformity)

Doctrine Diagnostic – Reflection: #

Ask yourself:

Are you trying to get everyone to live in one system, or are you building a system that accepts the world as it is?

If you choose the second, you are designing for the real world.

If you choose the first, you are designing for a world that does not exist.

Annex F Pattern: Staging Areas Are The Wrong Time To Start Trust

In Katrina, a relief organization arrived at a church parking lot in Bay St Louis and tried to take control of all supplies on site, including those already organized by the local community. The pastor accepted the supplies but rejected the attempt to manage his reality from the outside. This is what happens when an integrated system tries to snap onto a federated environment without pre-existing trust or agreements.

Read the full Field Note: Staging Areas Are The Wrong Time To Start Trust

Field notes and examples #

- Don’t Build an Army of Conscripts When You Need a Coalition of Allies

- Field Note: When Everyone Uses the Same Words But Means Different Things: Why Integration Fails When Vocabulary Collapses

- Field Note: The Human Cost of Interoperability (and the Legal Cost of Speed)

- Field Note: Compass-X Recognition Patterns and Strategic Framing

- Field Note: Sorting the 20-Year Backpack

- Documentation as Credibility Infrastructure

- The Scalpel vs. The Swiss Army Knife: When Solo Integration Beats Federation

- Stranded in Vienna, Responsible in Kyiv

- Respect The Envelope: Why Legal Is Not Always Safe

- Gates That Matter: Task Books, Checkrides And Real Safety

Last Updated on February 22, 2026