The technical agreements that stabilize interfaces, reduce ambiguity, and enable useful interoperability #

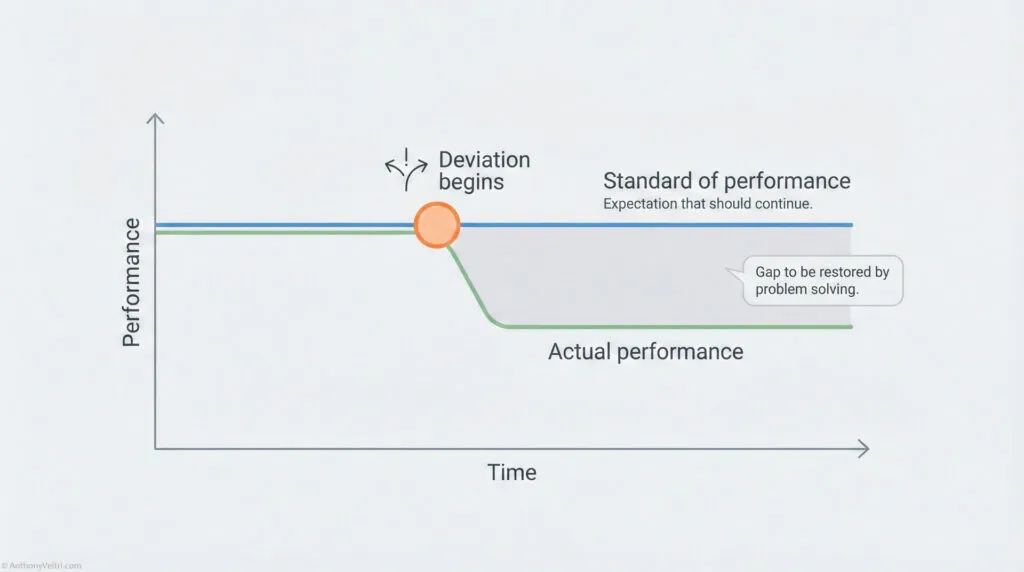

Doctrine Claim: Without a Data Contract, every system update is a potential outage for your partners. Contracts stop the “silent drift” of schemas and timestamps that breaks mission tempo. This is the technical agreement that turns a data feed from a “leak” into a “product.”

1. Purpose of Data Contracts #

Data contracts define the expectations for information flowing across boundaries.

They create predictability where partner diversity, schema drift, and leadership-driven change would otherwise create chaos.

Data contracts exist because:

- systems evolve independently

- partners update on different cadences

- schemas drift silently

- timestamps degrade

- formats vary

- upstream decisions ripple downstream

Without data contracts:

- small deviations cause large failures

- ingest pipelines break

- partners misunderstand requirements

- errors cascade

- analysts lose trust

- mission tempo degrades

Data contracts stabilize the technical boundary so humans can work with clarity and autonomy.

2. Why Data Contracts Matter #

Data contracts are essential for:

- federation

- useful interoperability

- degraded operations

- distributed decisions

- interface ownership

- preventing rework

- preventing schema drift

- protecting high tempo work

- predictable partner integration

Data contracts reduce:

- ambiguity

- unplanned outages

- mismatched assumptions

- brittle behavior

- reprocessing

- ad hoc fixes

- politics around correctness

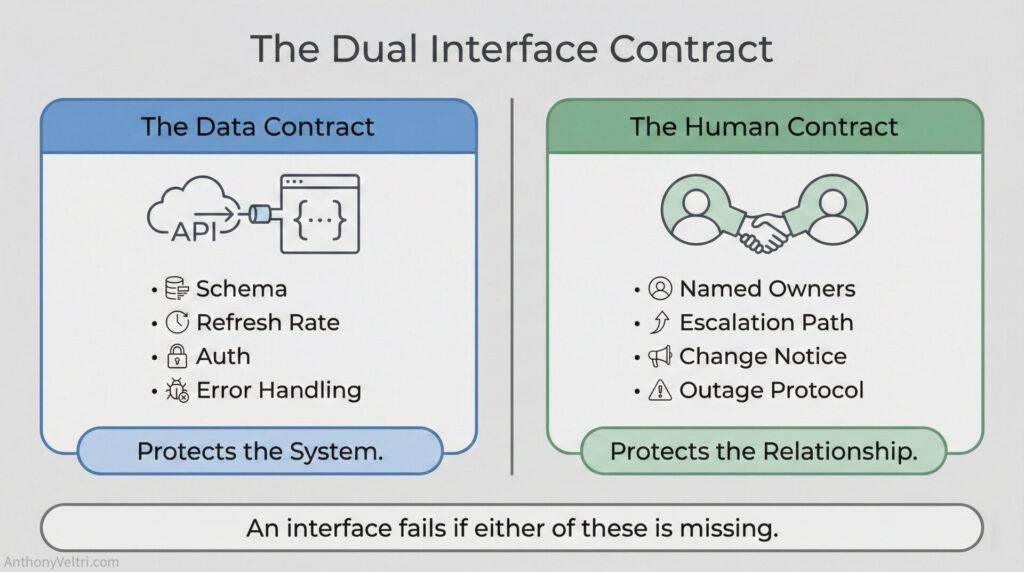

They are the technical version of human contracts and must be paired with them.

3. The Ten Required Elements of a Data Contract #

A complete data contract defines ten expected behaviors.

1. Schema definition #

Fields, types, optional vs required, maximum tolerances.

2. Geometry rules (if applicable) #

Projection, resolution, topology expectations, tolerance for errors.

3. Time rules #

Timestamp fields, timezone assumptions, publish window, acceptable drift.

4. Refresh cadence #

Expected update frequency; acceptable minimum and maximum.

5. Versioning model #

Major, minor, or patch level changes; deprecation rules.

6. Authentication and authorization #

Methods, token refresh expectations, fallback conditions.

7. Error signaling #

How unexpected conditions are communicated; expected error codes.

8. Fallback behavior #

What happens if updates stop, timestamps drift, or schema partially degrades.

9. Publishing expectations #

Minimum viable publication; required attributes during crises or high-profile cycles.

10. Change management #

How contract changes are communicated, approved, and rolled out.

If even one of these ten is missing, the boundary becomes fragile.

4. Data Contract Altitudes #

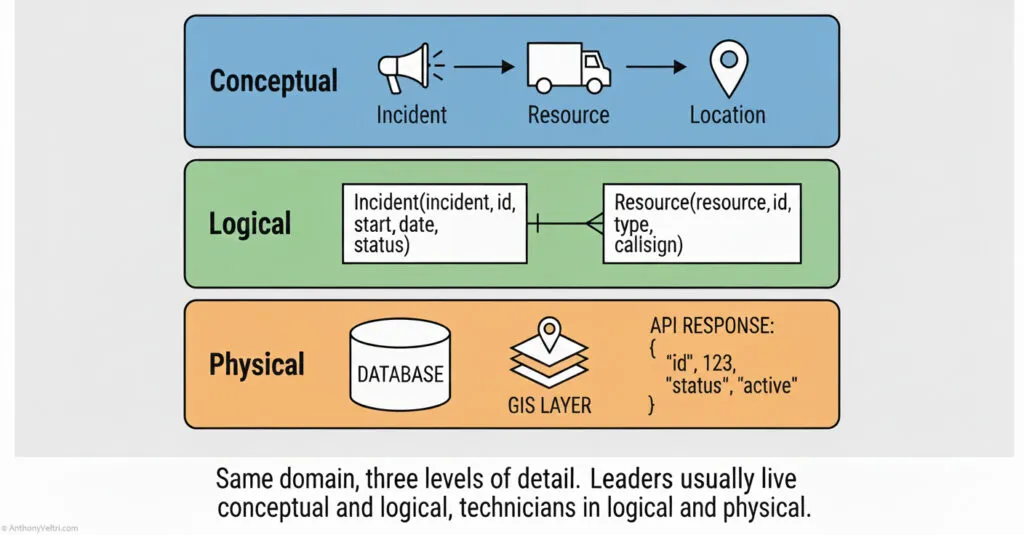

Data contracts operate across three levels.

Altitude 1: Technical correctness #

Operators and engineers ensure the data meets field level expectations.

Altitude 2: Process correctness #

Managers ensure the contract is followed, updated, and communicated.

Altitude 3: Intent correctness #

Leadership ensures the contract supports mission and strategic outcomes.

Failures occur when:

- leadership adds requirements without understanding downstream impact

- managers fail to protect technical boundaries

- operators do not understand the intent

- schema changes are pushed outside of agreed processes

This describes both mission systems and the FRN environment.

5. Data Contracts and Doctrine #

Data contracts directly support:

- federation vs integration

- useful interoperability

- degraded operations

- preventive and contingent design

- interfaces and ownership

- decision drag reduction

- commitment over compliance

A data contract is not a bureaucratic artifact.

It is a stabilizing force that keeps the system coherent under stress.

6. Business Example: Federal Register Notices (FRNs) and the cost of no data contract #

FRNs are a perfect high visibility case of failed data contracts.

Common problems we saw:

- leadership added fields on a whim, without verifying business need

- new mandatory fields appeared during review cycles

- teams used inconsistent definitions for the same fields

- some attributes were non negotiable legally, others were preference based

- timelines shifted without communicating impacts

- operators and editors were forced to reverse engineer meaning

- revisions cascaded across teams because there was no baseline

These are classic failures that occur when a data contract is missing.

To fix this, our team created a practical data contract even if we did not name it that:

- locked required fields

- defined optional fields

- stopped leadership driven schema drift

- clarified meaning of attributes

- prevented unnecessary rework

- stabilized expectations across editors, analysts, and leadership

- ensured the FRN met legal standards without endless thrash

- restored predictability

What we created was a data contract for legal publication.

It prevented chaos even though the content was not technical in the traditional sense.

It was data.

It required rules.

FRNs succeed only when the schema is stable.

7. System Example: iCAV and the federated ingest layer #

In iCAV, data contracts took the form of:

- partner specific ingest profiles

- expected schema shapes

- fallback acceptance rules

- geometry tolerance

- time drift tolerance

- metadata expectations

- caching rules

- versioning logic

These contracts allowed:

- partners to publish imperfect data

- ingest to tolerate upstream variation

- the viewer to display partial truth

- analysts to trust the picture

- engineers to isolate failures

Without data contracts, federation collapses.

With contracts, it scales.

8. Data Contract Template (Paste Ready) #

Here is your reusable template for WordPress:

Data Contract Template

Purpose:

Describe what this data supports and why it matters.

Schema:

Required fields:

Optional fields:

Data types:

Range and tolerance:

Geometry (if applicable):

Projection:

Resolution:

Topology expectations:

Error tolerance:

Time Rules:

Timestamp field(s):

Timezone convention:

Acceptable drift:

Refresh Cadence:

Expected update rate:

Minimum cadence:

Maximum cadence:

Versioning:

Major changes:

Minor changes:

Patch changes:

Deprecation path:

Authentication:

Method:

Token rotation:

Fallback behavior:

Error Signaling:

Codes:

Messages:

Retry rules:

Fallback:

What happens when updates stop or degrade?

Minimum Viable Publication:

What must still be sent even when the system is stressed?

Change Management:

Notice window:

Channels:

Approval process:

9. Cross Links #

Data contracts are directly supported by:

- Annex A: Human Contracts

- Annex C: Interface Ownership

- Principle 7: Interfaces break first

- Principle 10: Degraded operations

- Principle 12: Emergent resilience

- Principle 14: Decision drag

- Principle 19: Commitment over compliance

Data contracts prevent technical drift.

Human contracts prevent interpersonal drift.

They must work together.

10. Doctrine Diagnostic – For Reflection: #

Ask yourself:

Where in your system do people argue about data meaning?

Where do fields change informally?

Where do updates break downstream code?

Where do external stakeholders introduce changes without impact review?

These are signs of missing data contracts.

Write the contract.

Stabilize the boundary.

Reduce the drag.

Last Updated on December 5, 2025