Field Note: The Gift of Weaponized Compliance

Scene: Willamette Valley, Oregon (2010)

I had been a supervisor for maybe a week when I met him. He was retiring in about 30 days after a 40-year Forest Service career. He was the union steward. Other managers had warned me about him.

I decided not to fight someone with one foot out the door.

“Listen, I understand you’re leaving in about a month. Congratulations. Can you help me be successful with the next group of people? Can you share anything with me about this organization that would help me do a better job?”

I think that disarmed him. Maybe he expected the adversarial relationship he’d had with the previous supervisor. Instead, I invited him to tell me about his experience. And he did.

He gave me an original Forest Service handbook. I don’t know exactly how old it was, but given his 40-year career, it could have been from the 1970s or earlier. He told me about his role as union steward. Not from the perspective of “here’s how I beat the system,” but from the perspective of “here’s how you can be a better supervisor.” He did not have to talk to me. He did. I am grateful for that opportunity to connect.

His advice: “Always have your story straight.”

Always have cover for action and location. Always have a plausible explanation for the decisions you made. Never deviate from that explanation. And be ready for “that’s not the way it was explained to me” or “that’s not the way I understood it.”

He said this as a warning. As a teaching tool. He was legitimately trying to help me.

What Weaponized Compliance Looks Like in Practice

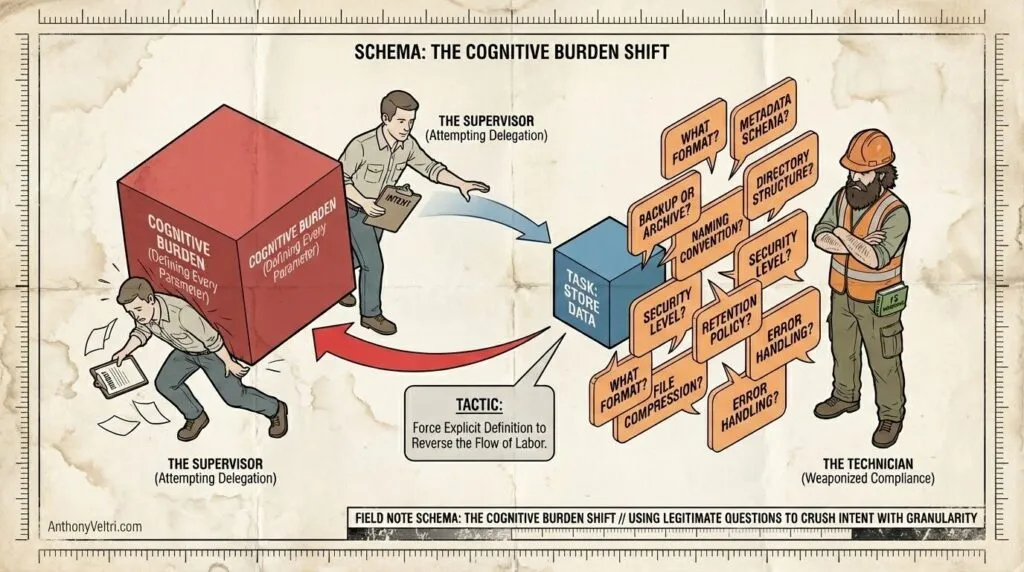

An employee receives a task. Instead of interpreting the intent, they force you to explicitly define every parameter.

The Scenario: “Store this data.”

- “In what format?”

- “What file naming convention?”

- “What directory structure?”

- “What metadata schema?”

- “When you said ‘store,’ did you mean backup or archive or working copy?”

Each question is legitimate. Taken together, they shift the entire cognitive burden of the task back onto you. If you don’t answer every single question explicitly, you get: “Well, that’s not the way it was explained to me.”

The employee isn’t technically wrong. They’re forcing you to do the work of defining the work.

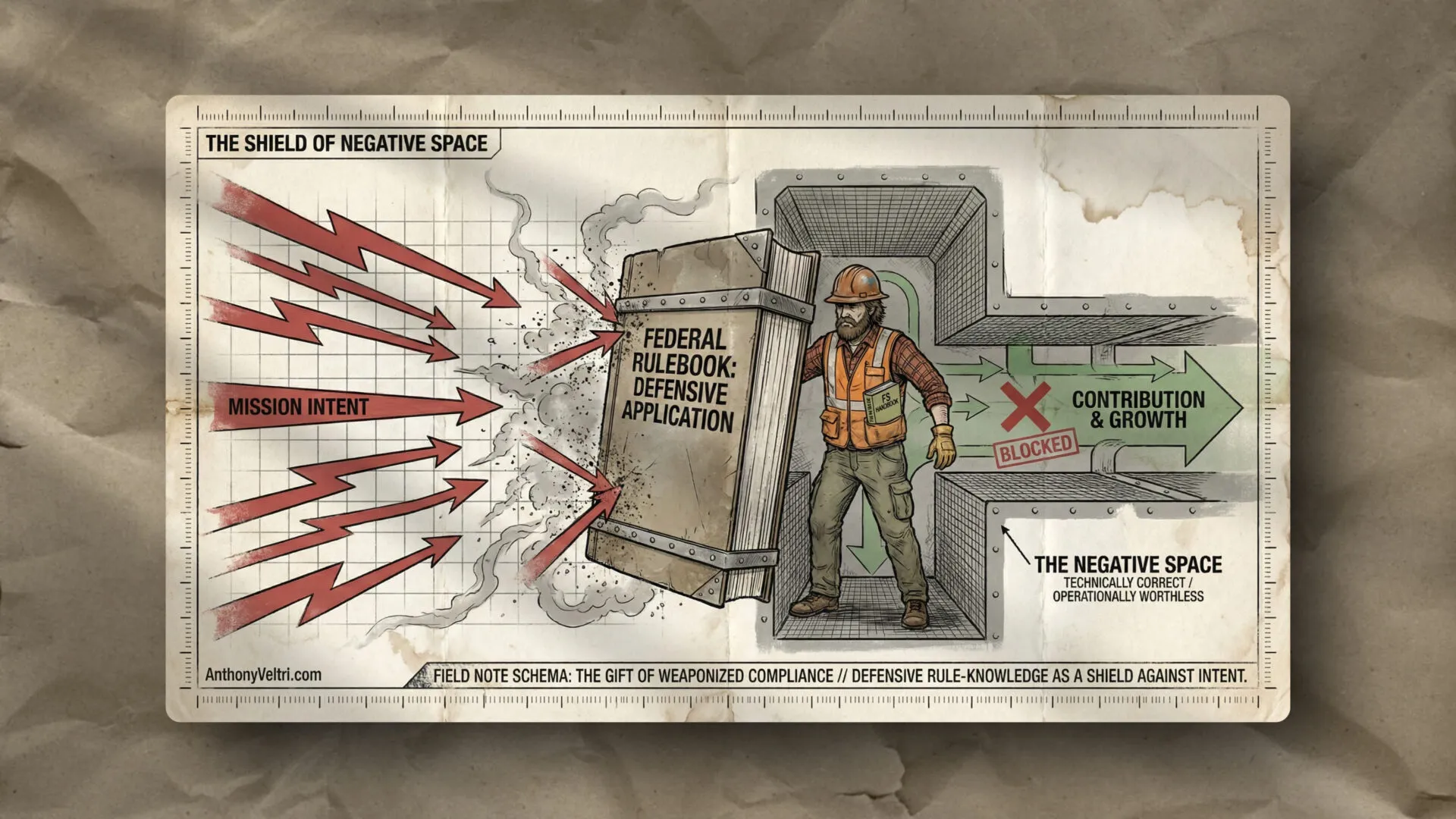

Another Pattern: “We need to complete this report by Friday.” Employee does nothing Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday. Friday afternoon: “You said complete it, you didn’t say start it. I was waiting for the other dependencies.”

Technically correct. Operationally worthless.

The Sophistication: They’re not doing the wrong thing. They’re also not doing the right thing. They’re occupying the negative space. Avoiding violations while contributing nothing.

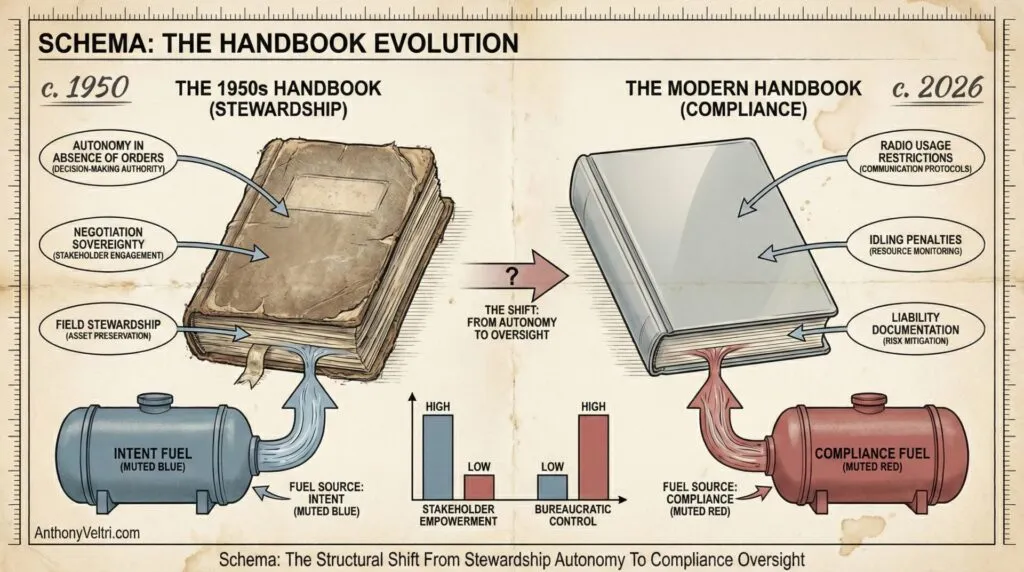

The Evolution of the Handbook: From Stewardship to Oversight

The old handbook was a revelation. It detailed how a Forest Service District Ranger was to handle the business of stewarding the government’s forests in remote areas of the West. There were no cell phones. You couldn’t call Washington for guidance on everything.

The Operating Assumption of the (pre) 1950s Handbook:

- How to negotiate for supplies when purchasing supplies.

- What to do with people trespassing or illegally cutting timber.

- How to run a ranger district if the Washington office or higher headquarters could not be reached.

The core logic: Here’s what to do in the absence of somebody to tell you what to do.

Contrast that with the Modern Forest Service Handbook:

- What you are allowed to listen to on the radio in a Forest Service vehicle.

- When you are allowed to let a vehicle idle.

- Compliance training requirements for rules you should theoretically be aware of so you can be penalized for breaking them.

The old handbook assumed autonomy and stewardship. The modern handbook assumes compliance and oversight. This shift mirrors the transition from “Commitment Gates” to “Compliance Gates” discussed in Doctrine 24. When the culture fails to steward the individual, the individual uses the rules as a shield.

Break

I never encountered anyone else at his level of proficiency with this tactic. But I was aware of it for the duration of my tenure. If I had taken a hard-line supervisor approach, he never would have shared this information with me. And even if I had “won” (let’s say I managed to get this guy fired right before he retired) to what end? What would I have won?

Instead, I received a gift. Not just understanding weaponized compliance, but understanding the motivation behind it. This guy was an outstanding analyst and ecologist. Well-respected by employees. He just didn’t want to be trifled with.

The Previous Supervisor and the Egalitarian Trap

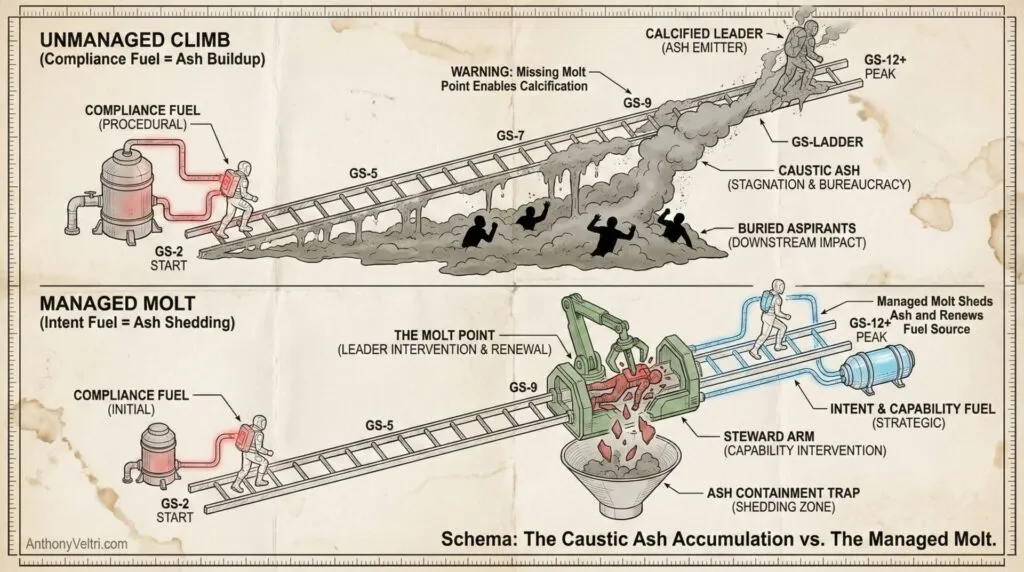

The Forest Service sells itself on an egalitarian story: you can go from GS-2 field technician to GS-15, maybe even to Chief of the Forest Service. There are stories of chiefs who started as seasonal employees, who started at the front desk. It’s a nice story. And it’s still partially true.

The previous supervisor had come up from GS-2 to GS-12 or GS-13. She had climbed the entire ladder from the bottom.

What got her from GS-2 to GS-12:

- Follow the rules

- Work harder than everyone else

- Don’t make mistakes

- Do exactly what you’re told

- Prove you deserve the next step

The problem isn’t the climb: it’s what fuels the climb.

An ascent fueled by compliance leaves a caustic ash. The behaviors that earned each promotion become calcified (unless they’re actively managed; unless someone makes you aware you need to molt and develop at each stage).

The Requirement to “Molt”

Each stage of the federal ladder requires a fundamental change in how you process information:

- At GS-2 (The Task Recipient): Following rules and working hard gets you promoted. Accuracy is the only metric.

- At GS-9 (The Intent Interpreter): You need to start interpreting intent. You are no longer just doing the task; you are understanding why the task exists and adjusting for the environment.

- At GS-12 (The Intent Enabler): You need to enable others to interpret intent. You are no longer the doer; you are the steward of the mission’s logic.

If no one tells you this (if no one manages your transition at each stage) you keep applying more of what worked before.

She wasn’t a bad supervisor. She was doing more of what worked for her. Demanding the same from everyone else. No one had told her she needed to evolve past compliance. The ash: rule-following applied to yourself, applied to others, applied everywhere, long after it stops being useful.

And people respond by becoming very good at protecting themselves.

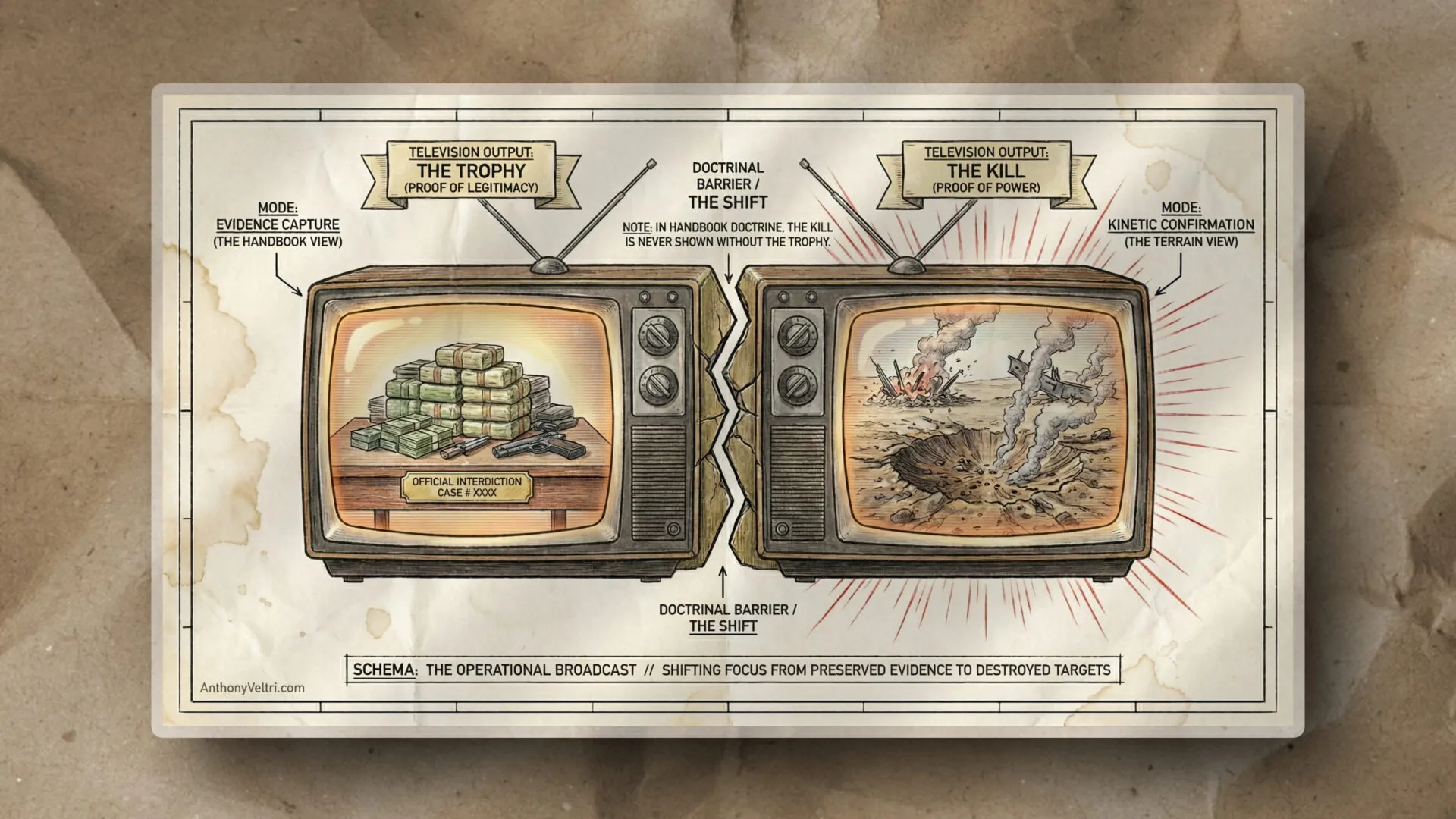

Realization: Same Game, Different Objectives

He used his knowledge of the rules to protect himself from doing the wrong thing. I used my knowledge of the rules to do things that probably needed permission but weren’t explicitly prohibited.

I was still skirting edges. I still needed my story straight, just like he did. Same knowledge. Same game. Different objectives.

Schema: Defensive vs. Offensive Rule Knowledge

Weaponized compliance is the defensive application of the same rule-knowledge that could enable contribution. The difference isn’t knowledge. It isn’t capability. It’s whether you’re operating defensively or offensively.

The Defensive Game:

- Protect yourself; don’t make mistakes.

- Know the rules so you can’t be blamed.

- Force explicit definition of every task.

- “That’s not the way it was explained to me.”

- Occupy the negative space between wrong and right.

The Offensive Game:

- Enable action; take calculated risks.

- Know the rules so you know what you can probably get away with.

- Interpret intent and move forward.

- Have your story straight when challenged.

- Do things that might need permission but weren’t explicitly prohibited.

The employee I inherited wasn’t malicious. He was well-respected. Competent. An outstanding ecologist. He just didn’t want to be trifled with anymore. After 40 years of rule-following supervisors demanding more of what worked for them, he became exceptional at the defensive game.

And you can’t blame him for it. If the organization optimizes for compliance over contribution, if supervisors treat employees as liabilities to manage rather than capabilities to steward, the defensive game is the rational response.

The Lesson for Stewards

If you approach someone playing the defensive game with a hard line, you get weaponized compliance. They run out the clock. You get nothing. If you approach them with respect for what they’ve learned, you might get the gift.

I asked him to help me be successful. He told me how the game worked. And then he left.

I used what he taught me. In 2012, I handled a critical incident “correctly by the book” but not “the right thing by the human.” I knew it at the time. I knew I had a shortcoming. I addressed it. Not from a hero perspective, but from an “oh shit, I need to fix this” perspective.

And despite that shortcoming, people recognized: “This person is noticing something that’s beneficial to all of us.” I got supervisor of the quarter for it. I was asked to facilitate the Partnership Council in the Pacific Northwest Region (the interface between management and union-eligible employees).

Not because I was perfect. Because I was paying attention to the gap between correct and right. I learned to see from both perspectives. I learned to play the same game he played, just with different objectives.

Because a retiring union steward with one foot out the door decided to teach me instead of just running out the clock. That was the real gift.

Last Updated on February 24, 2026