Reclaiming the Right to Orchestrate: Decision Altitudes and Why Your Chisel Doesn’t Give You the Right to Judge My Output

The Opening Salvo: A Standard of Mutual Sovereignty

Let me be clear: this is not a field note about the inferiority of manual craft. I have a bone-deep respect for the “Chisel Purist.” My lineage is built on the scent of physical resistance. I grew up with the unmistakable, heavy smell of a hot engine bay from one grandfather who was a mechanic. I knew the “delicious,” earthy scent of freshly mixed concrete, churned by hand (the original ASMR) in a wheelbarrow by my other grandfather who was a mason. I have the grit of sawdust in my lungs and the smell of darkroom fixer on my hands.

If you choose to fell a tree with a hand-axe or mix your mortar in a wheelbarrow, you are engaging in a noble form of Primitive Friction. You are preserving a connection to the material that is vital and rare. I have no right to judge your process, and I never would.

But that is rarely the direction the judgment flows.

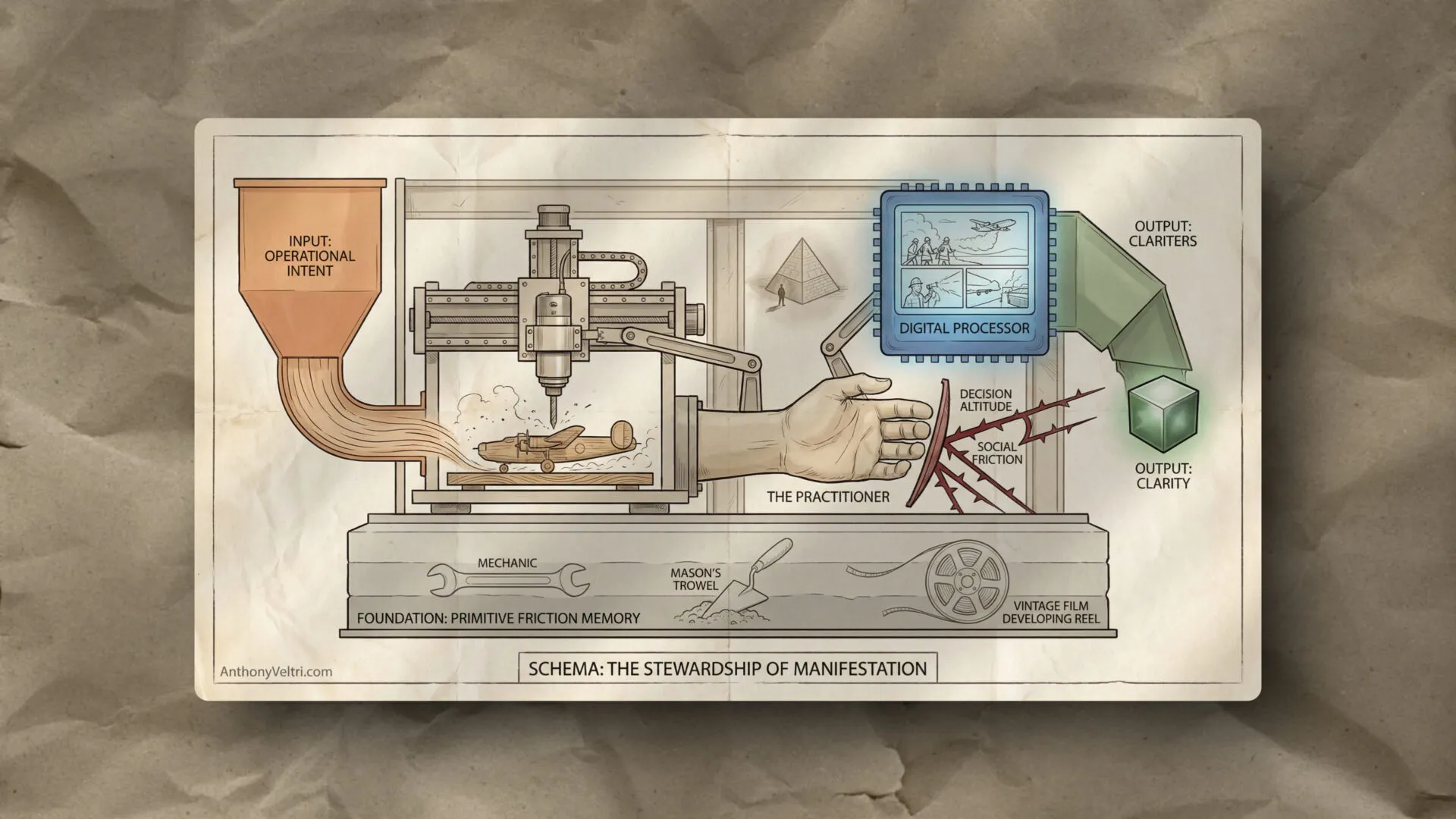

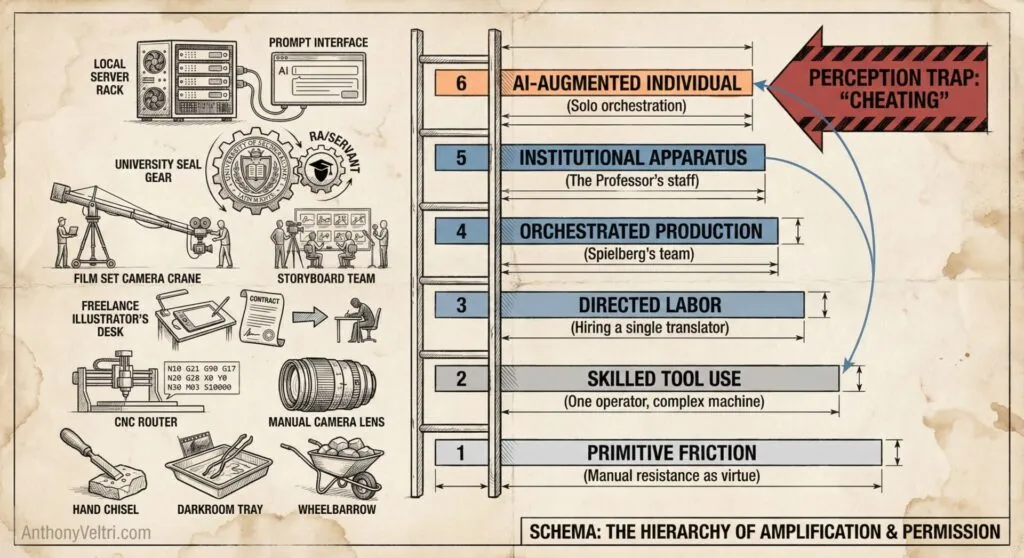

The problem arises when the person with the chisel (or the person who can’t even maintain their own bicycle) claims that their friction is the only legitimate source of “making.” When they look at a 4-axis CNC carving or an AI-augmented storyboard and say, “Yeah, but you didn’t make that,” they are attempting to enforce a Permission Structure based on their own technical limitations. They assume that because I bypassed the physical struggle, I also bypassed the Operational Logic. They lack the Decision Altitude to distinguish between the tool and the intent.

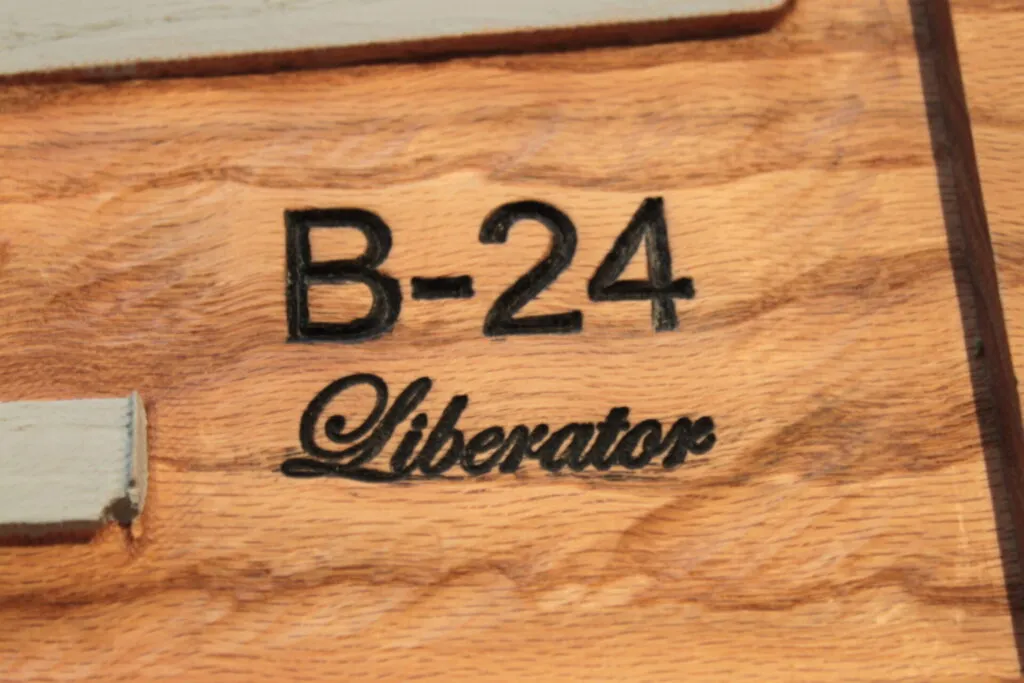

Manifested Intent (Corvallis, 2010). A two-and-a-half-D carving on oak. The critic saw a machine; the practitioner saw a requirement for a specific person at a specific moment.

Scene: Corvallis, 2010

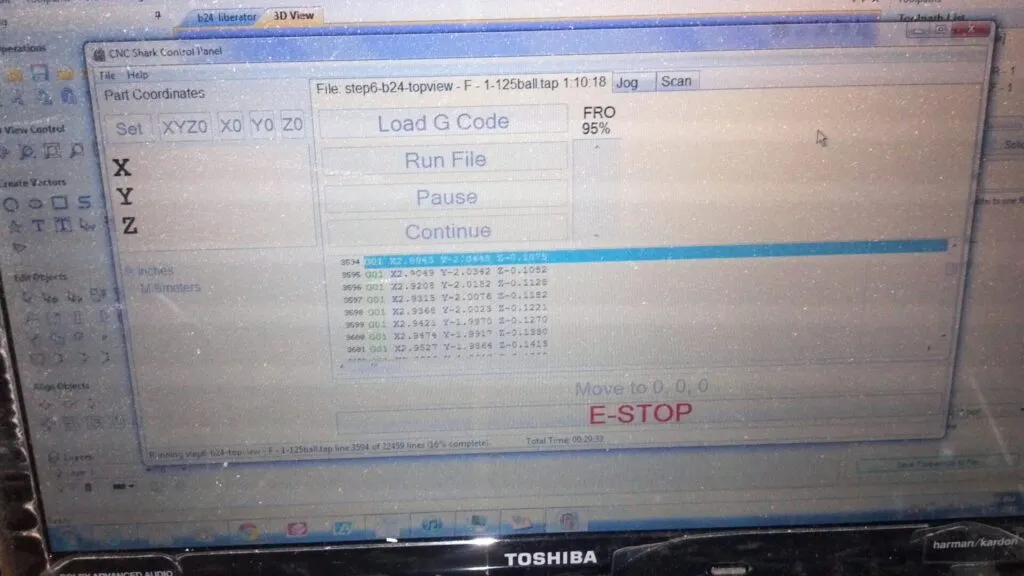

I’m standing in my garage with a dining-table-sized CNC router, having just finished a two-and-a-half-D carving of a B-24 Liberator on oak for my grandfather. I found a 3D model, translated it to G-code, calculated feed rates for oak (one of the hardest woods to route, as i soon discovered), flattened the work surface, managed the toolpaths. A person we knew in Corvallis, someone I’d given rides to, someone whose bike chain I’d helped fix, looked at the finished sign and said: “Yeah, but you didn’t make that.”

She rode her bike everywhere but couldn’t change a tire. She couldn’t maintain her own bicycle. But she could see that I’d used a machine, so in her view, the machine did the work, not me.

That was the moment I realized the question itself was the trap.

That B-24 sign wasn’t the only thing I made on that router. There’s a wooden sign that still hangs in the Forest Service office in Corvallis. It says “Geospatial” with the USFS shield carved in relief. I made it because the office needed better wayfinding, and a professionally carved wooden sign fit the context better than a printed placard. Same process: found the vector files for the shield, generated the toolpaths, calculated feed rates, manifested the intent.

Would that have changed the person’s evaluation? No. Her framework for “making” didn’t distinguish between personal gifts and professional infrastructure. It didn’t matter whether the sign served an operational mission or hung on a family member’s wall. She saw the tool, not the orchestration. If she’d known about the Forest Service sign, she would have said the same thing: “Yeah, but you didn’t make that.”

The evaluation framework itself was broken. It couldn’t see the difference between using a tool to manifest intent and letting a tool do generic work. That’s the pattern that still exists in 2026: people evaluate the tooling, not the outcome. Whether it’s a CNC router or an AI, if you used amplification, you didn’t “really” make it.

Break: Who Gets to Use Amplification?

I didn’t carve that B-24 by hand. I couldn’t have. I don’t possess the skill set to fell the tree, split it with a froe, plane it with hand tools, and carve the details with chisels. But I absolutely made that sign. I made the decision that this specific B-24 needed to exist on this specific piece of oak at this specific moment for this specific person. (side note: while I have used all of those tools individually, I do not possess the level of aggregate skill to produce such a sign via hand tools alone.)

The question itself is the trap. The standard being applied wasn’t about the quality of the sign. It was about whether I had “earned” the right to amplify my intent through a machine.

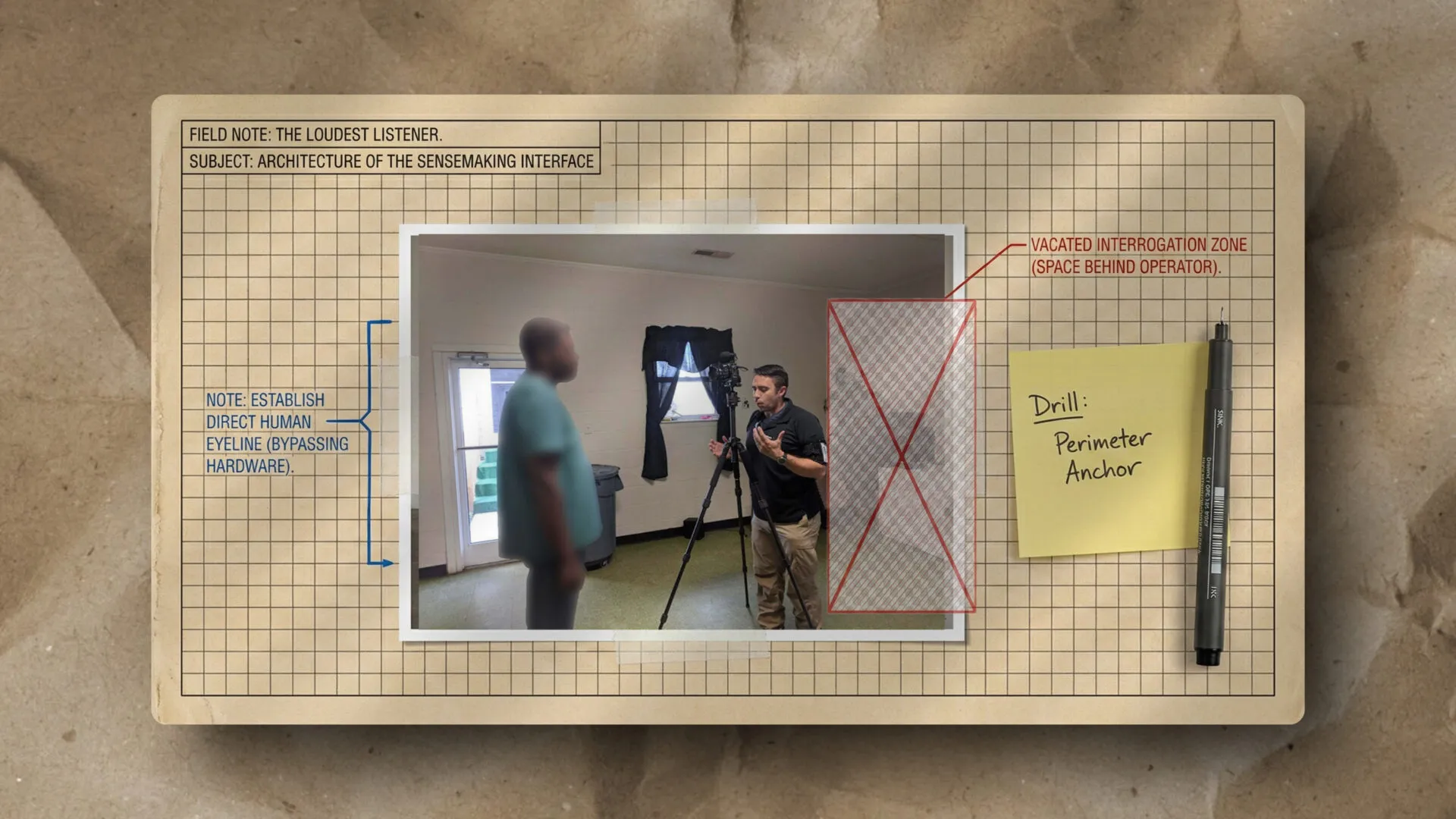

The Mission Critical Transition

Years later, working in federal service, I encountered this same friction in strategic communication. We were trying to recruit wildland firefighters and other mission-essential occupations nationally for the Mission Critical Job Series. I’d be interviewing fire people who, let’s just say, were not media trained (and nor should they have been).

In the “old world,” if you wanted to communicate a complex operational sequence, you usually just wrote a text-heavy memo that people skimmed or ignored. You didn’t even try to sketch it because the friction was too high. The choice was between a paragraph of text or silence.

I pushed past that default. On my own dime, I hired illustrators to draw six-cell storyboards. These weren’t for tactical EOC work. They were for strategic communication that text or PowerPoint slides couldn’t handle alone. They provided clarity about the objective and confidence in the process.

For example, I might need to show a coordination sequence: a Type 1 Incident Commander at a drop point, coordinating via radio with a Hotshot crew, while a helicopter dropped retardant on a ridge line in the background. In reality, it was generally nowhere as grandiose as a Bruckheimer cinematic sequence, but the clarity was the requirement.

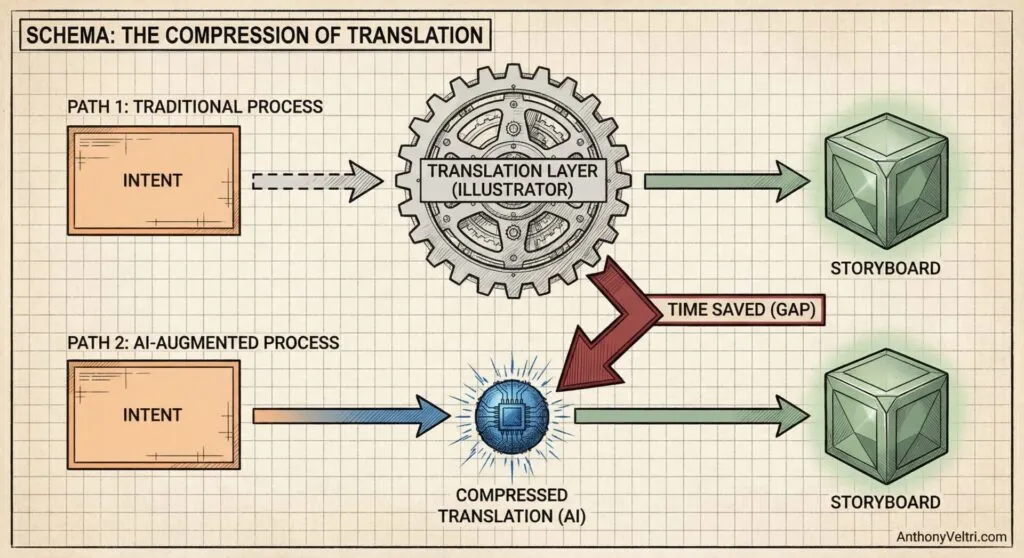

In that old world, I had to write the description, send it to an illustrator, wait for a sketch, and hope they understood the tactical positioning of the resources. The illustrator was the Translation Layer. They interpreted my operational words into a visual reality.

Today, that translation layer is compressed. I can feed that exact operational description into a local AI model and have a near-perfect storyboard cell in seconds. The “translator” middleman is gone. The distance between my operational thought and its manifestation has shrunk to almost zero. This doesn’t mean the illustrator’s skill wasn’t valuable; it means the skill has been absorbed into the tool.

Now, in 2026, I can generate those drawings myself in a fraction of the time. The output isn’t materially different in function. It still provides clarity. It still helps people see the operation. But now people ask: “Did you actually make that?”

Orchestration as a Tier-1 Skill

Steven Spielberg has publicly described storyboarding as something he sometimes does with crude stick-figure sketches that get translated by professional storyboard artists, and something he sometimes skips entirely. Either way, we still credit the orchestration.

Spielberg operates at a decision altitude where the question “did you personally draw the frames” is category error. Sometimes he storyboards everything. Sometimes he storyboards nothing. Sometimes he sketches stick figures (he notes he is not a particularly good illustrator) and delegates the translation to artists. The constant is not the tool. The constant is stewardship of intent across a thousand moving parts.

We need to stop defending orchestration as a “shortcut” and start claiming it as a Tier-1 Skill. In any complex system (whether it is a movie set, a research lab, or a federal emergency response), the person who can hold the entire operational logic in their head and manifest it into reality is the most valuable asset in the room. Spielberg isn’t “lazy” because he doesn’t draw. He is a visionary because he can maintain the Decision Altitude required to ensure a thousand moving parts serve a single mission.

When I prompt an AI, I am not “pushing a button” for a random result. I am architecting intent. I am calculating the digital “feed rates” and “toolpaths” of information. If we celebrate the executive with an assistant and the professor with an army of research associates, we are celebrating orchestration. The AI-augmented practitioner is simply doing that orchestration solo.

The Research Associate: The Professional Servant-Heir

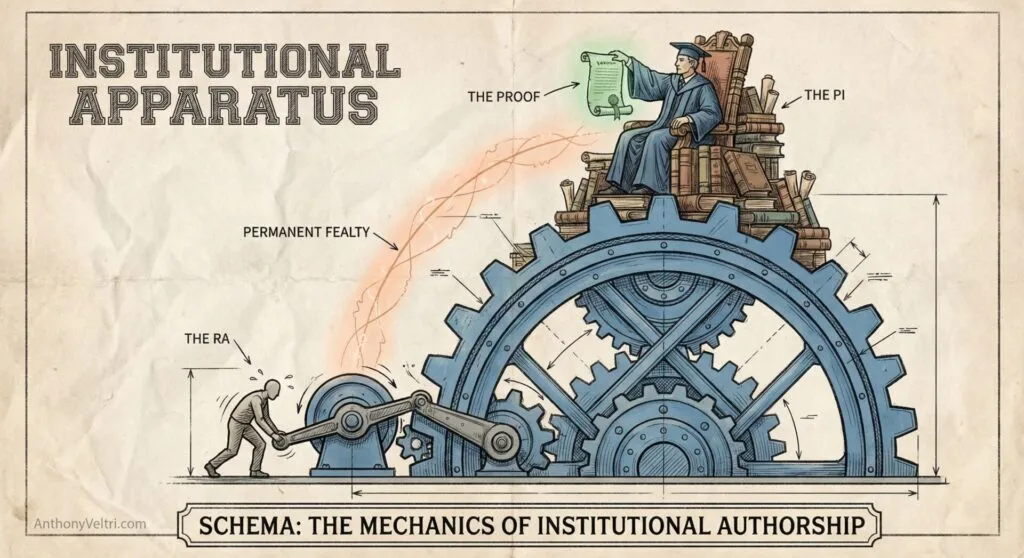

Consider the modern academic hierarchy, specifically the Research Associate (RA). I once knew an RA (a man of immense technical competence) who existed in what started as a state of perpetual, high-fidelity subordination. He was, for all intents and purposes, a pharaoh’s servant: one of those essential assistants who, in an earlier age, might have been expected to be buried with the Principal Investigator (PI) to ensure the continuity of service in the afterlife.

His “making” was not limited to the laboratory or the library. He performed “other duties as assigned” that spanned the entire spectrum of the PI’s existence. He cleaned the professor’s yard; he managed the household; he ran the errands that cleared the way for the “Visionary” to think. More importantly, he executed the granular, exhausting labor of the research itself: the data entry, the primary analysis, and the mechanical assembly of the proof.

However, this was not a story without redemption. What began as a strictly subordinate relationship evolved over decades into a bond of permanent fealty. As age caught up with the professor, the relationship shifted from mere employment to a deep, mutual reliance. There was genuine gratitude from the PI for the stewardship of his life and work.

In a rare turn of fate, because the professor died without heirs, this RA was named in the will and inherited the estate. He finally got the “good deal” for his decades of service. We don’t usually hear of a Pharaoh passing his wealth to the servant at the base of the pyramid, yet in this outlier case, the loyalty was honored.

But notice the standard: we never once questioned whether the PI “made” that research. We did not strip the PI of his authorship because he did not manually fumble with the spreadsheets or stain his own hands with the samples and data. We celebrated the Orchestration. We accepted a fundamental truth: the PI’s value was in the direction, the stewardship, and the final intellectual contribution. The PI orchestrated the RA to manifest a vision.

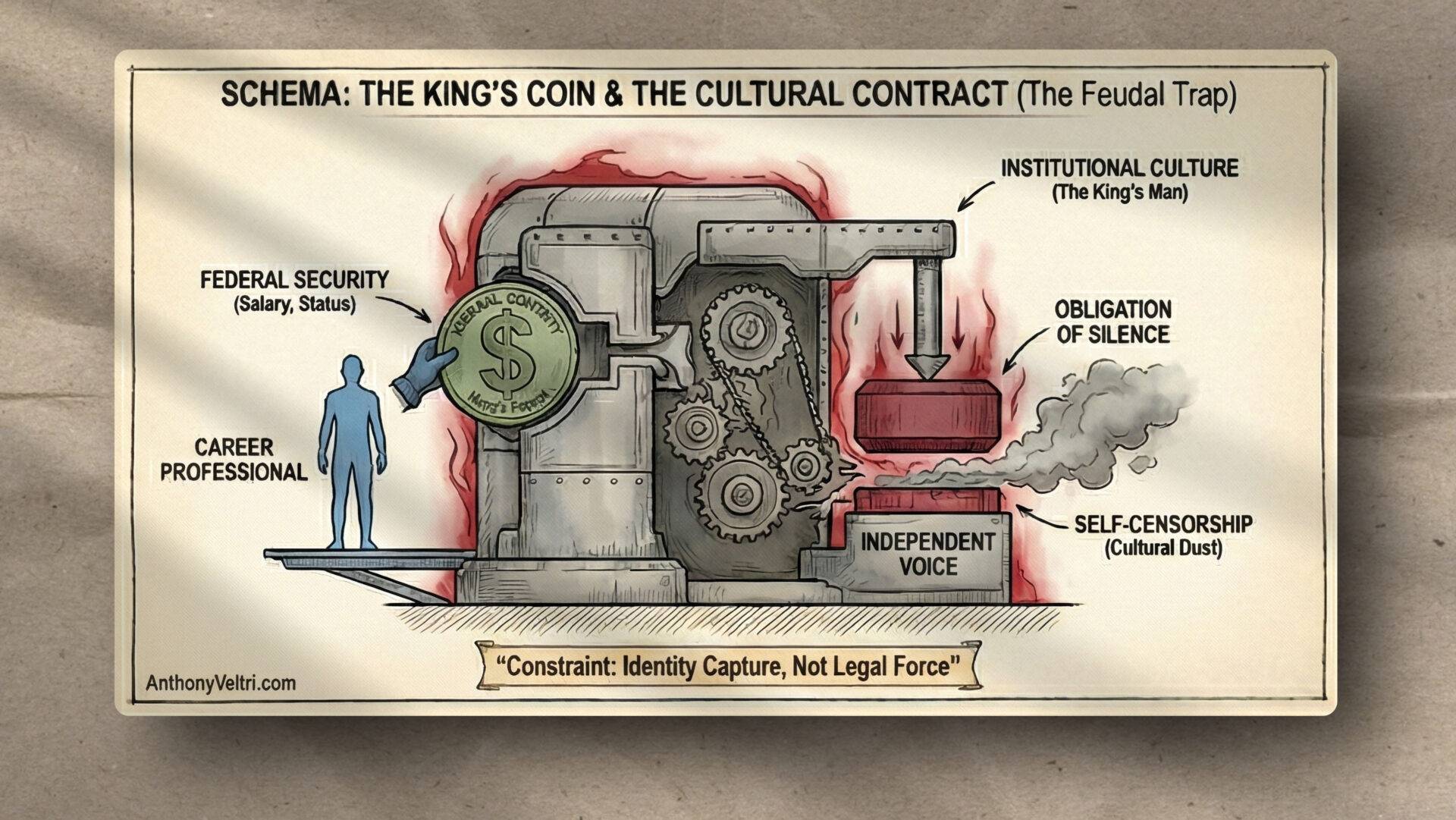

Yet, when an individual uses AI to bypass that servant-assistant relationship (when they replace the “Pharaoh’s Servant” with a local model), the institutional gatekeepers call it “cheating.” It turns out we are not protecting the craft of research or the “manual purity” of the data. We are protecting the Permission Structure. We are protecting the social standard that says you are only allowed to amplify your output if you are high enough in the hierarchy to hire human servants to do it for you.

This pattern repeats across every layer of our society:

- When an oligarch goes bankrupt, we say “that’s just business.” When a person goes bankrupt, we say it’s a moral failure.

- When a corporation automates manufacturing with robots, we call it progress. When an individual uses AI for writing, we call it cheating.

- When an executive has an assistant draft their emails, we call them efficient. When an individual uses AI for the same task, we call them inauthentic.

- When a wealthy person hires a tax accountant to optimize their return, we call them smart. When a regular person uses TurboTax, we warn them about the risks.

- When a company outsources to an offshore team, we call it business savvy. When an individual uses AI instead, we call them lazy.

The evaluation standard is inconsistent. It is not about the outcome. It is about who has permission to use amplification tools.

Schema: The Evaluation Question

The real question isn’t “did you make it?” The real question is: “Is this technology making humans better or faster at producing outcomes that matter?”

For me, the answer is clear. I’m producing the same clarity I always produced, but faster. The storyboards still work. The doctrine still teaches. The operational knowledge still transfers. The only thing that’s changed is the tooling.

But I think we’re asking the wrong evaluation questions:

Question 1: Is the metric “human time saved” or “outcome quality achieved”? If I produce a six-cell storyboard in 30 minutes instead of 3 days, but the clarity is identical, have I cheated? Or have I just gotten better at my job?

Question 2: Who gets to use amplification without stigma? Spielberg gets a team. Academics get research assistants (or servants, depending on the professor). Corporations get entire departments. Oligarchs get systems that insulate them from failure. But an individual using AI to amplify their own capability is seen as suspect. Why?

Question 3: What’s the threshold where orchestration becomes legitimate? If I hire one illustrator, am I still “making” the storyboard? What about a team of three? What about a team of ten? At what point does directing human labor become acceptable, but directing machine labor remains “cheating”?

Question 4: Does scale matter, or does intent matter? If a corporation uses AI to generate a thousand mediocre outputs, that’s innovation. If an individual uses AI to generate one precisely-targeted output that solves a specific operational problem, that’s cheating. The scale is backwards from the value.

Question 5: Are we protecting craft, or protecting gatekeeping? The woman in Corvallis couldn’t maintain her own bicycle, but she could judge my use of a CNC router. She didn’t have the decision altitude to see the orchestration. She saw the tool as the threat because she didn’t understand the work. Are we protecting the integrity of craft, or are we protecting the social permission structure that says some people get to use amplification and others don’t?

The Counter-Argument I Can’t Ignore

I need to be honest here. I grew up with the smell of fixer and stop bath on my hands. I stubbed my toe fumbling into the darkroom at 2 AM. I ruined good canisters of film because I hadn’t practiced my technique of getting film onto the reel enough. I was a photographer. That skill set helped pay for college through rock climbing sports photography.

And I felt the pinch when photography went digital. Then I felt it again when AI image generation arrived. Much like the illustrators I hired for storyboards, I watched viable skills become less viable. I can’t talk about how good AI amplification is without acknowledging that yes, it creates displacement.

The illustrators I hired weren’t doing generic work. They were translating my operational intent into visual clarity. They had real skill. They could take my description of a complex coordination sequence and turn it into something a firefighter in the field could understand at a glance. That translation skill mattered. Now I can do that translation myself with AI, but that doesn’t mean their skill isn’t valuable. It means the translation layer got compressed.

My film loading skills aren’t viable anymore. The illustrators’ hand-drawing skills are less viable. I still enjoy loading film from time to time, and if someone wants to know how, I can show them. But it’s not a professional skill anymore. It’s a hobbyist nostalgia. The question I don’t have a clean answer to is: what happens to specialized translators when the translation layer gets compressed?

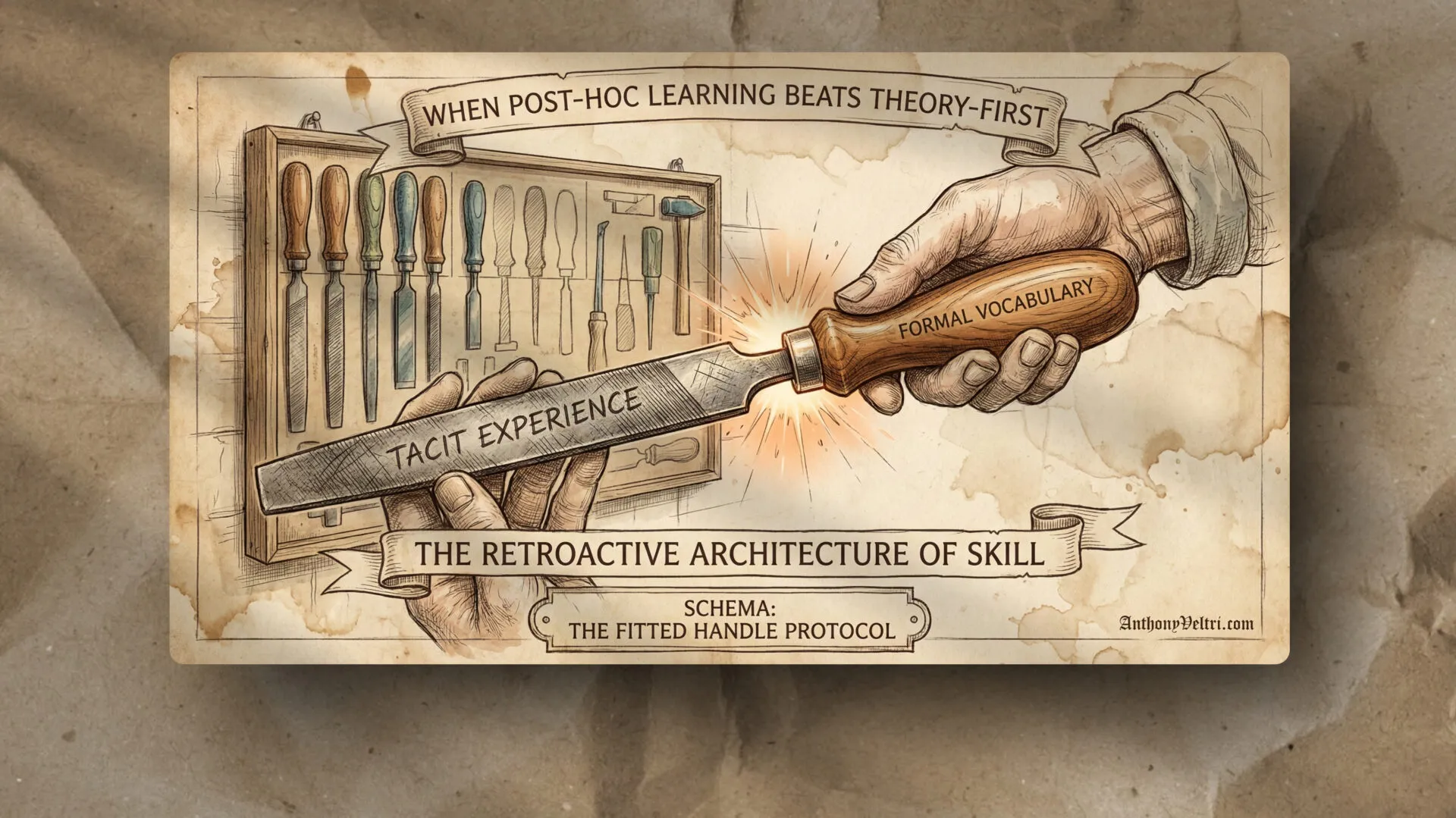

What we are witnessing is the Compression of the Translation Layer. Historically, if I had a complex operational idea, I needed a “middleman” to translate that idea into a visual or written asset, be it an illustrator, a photographer, or a junior staffer. That middleman was the translation layer.

The “pinch” I felt when photography went digital, and what the storytellers feel now, is the sound of that layer being flattened. The specialized skills of the “translator” (loading film, drawing cells, formatting spreadsheets) are being absorbed into the tool itself. This doesn’t make the skill “bad,” it makes it a non-professional technicality. The mission remains the same, but the distance between “Intent” and “Manifestation” has shrunk to almost zero.

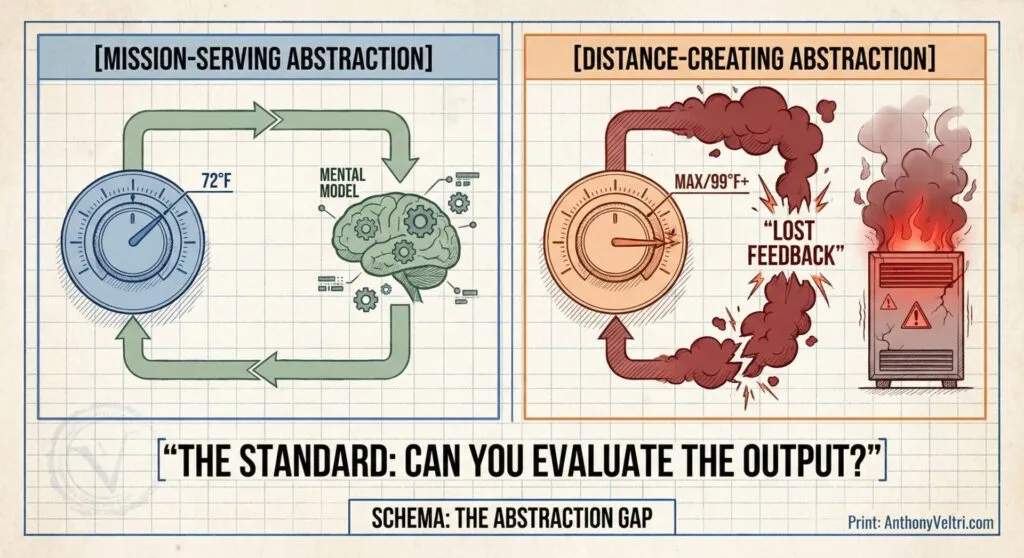

When Abstraction Serves the Mission vs. Creates Distance

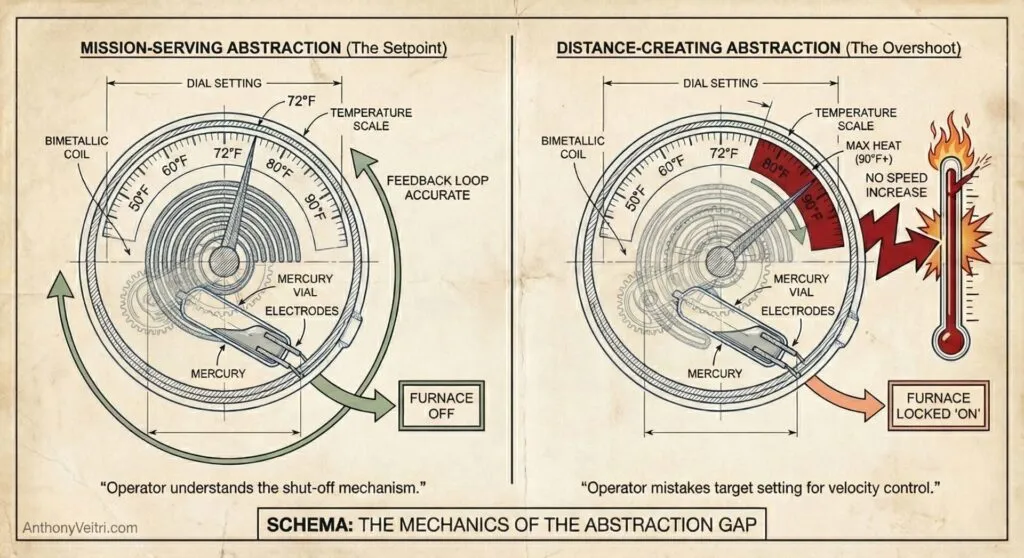

The abstraction isn’t inherently bad. The problem is the distance it creates from understanding. Take thermostats. A lot of people don’t know how a thermostat works. When we moved from mercury switch thermostats to relay-based or solid-state systems, it became even more abstracted. Not everyone needs to know how to mine mercury from the ground and safely encapsulate it in a switch in order to use a thermostat. But the distance from understanding creates problems.

You see people walk into a cold room and crank the thermostat all the way up to high, thinking it will make the room heat faster. They don’t understand the setpoint mechanism. They don’t know that putting it to high just keeps the heat on longer, it doesn’t make it go any faster. The abstraction created distance, and the distance created misunderstanding.

Abstraction serves the mission when it removes unnecessary friction while preserving understanding of the outcome. The CNC router abstracted away the chisel work, but I still had to understand feed rates, toolpaths, material properties. I couldn’t just push a button and get a result. I had to know enough to evaluate whether the output matched the intent.

Abstraction creates distance when it removes the understanding needed to use the tool responsibly or evaluate the output. Auto-correct that changes your meaning without you noticing. AI that generates plausible-sounding nonsense that you can’t recognize as nonsense. Thermostats that people misuse because they don’t understand setpoints. These create distance without providing the feedback loop that would help you learn.

The line isn’t “no abstraction” versus “all abstraction.” The line is whether you can take responsibility for the output. If you can’t tell when the tool produces garbage, you shouldn’t be using the tool. If you can tell, and you can correct it, and you can stand behind the final result, then the abstraction served the mission.

A thermostat serves the mission when it abstracts the mercury switch so you can focus on the temperature. It creates distance when you crank it to 90°F because you don’t understand the Setpoint Mechanism: you think you’re making it “heat faster” when you’re actually just ensuring it overshoots the goal and wastes energy.

The line for the modern practitioner is whether the tool provides Mission-Serving Abstraction or creates Distance from Understanding.

The Abstraction Standard. Stewardship requires the practitioner to understand the setpoint mechanism. If you cannot evaluate the output, the tool has created distance rather than clarity.

If you can take responsibility for the output (if you can tell when the tool is producing “plausible-sounding nonsense” and correct it) then you are still the maker. If you can’t tell, you aren’t a practitioner; you’re just a passenger. The making is in the manifestation, and the manifestation requires a setpoint. The problem isn’t the abstraction, it’s the lack of feedback loops that would teach understanding through use.

So Then… What Counts as Making?

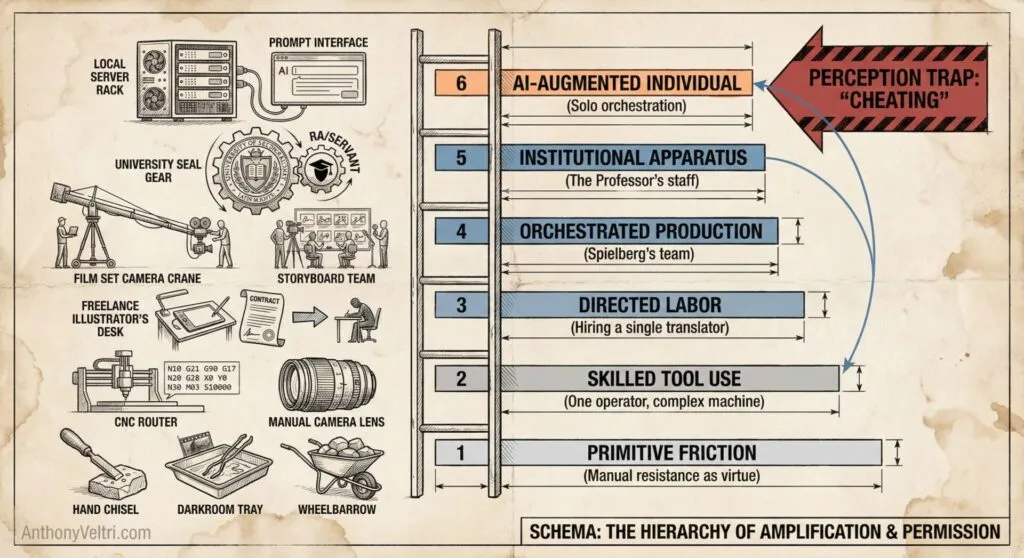

Let me try to map this out, because I genuinely don’t know where the line is:

Primitive Friction (Maximum Manual Labor):

- Fell the tree, split with froe, plane by hand, carve with chisels

- Mix chemicals, load film, develop in darkroom, print by hand

- Draw every storyboard cell with pencil and paper

- Who does this? Almost nobody professionally, some hobbyists and artisans

Skilled Tool Use (Single Practitioner with Power Tools):

- CNC router with G-code you write yourself

- Digital camera with manual settings you control

- Digital illustration software where you draw each element

- Who does this? Individual practitioners, small shops, specialists

Directed Labor (Small Team Execution):

- Hire one illustrator to execute your vision

- Hire one photographer to shoot your storyboards

- Hire one developer to build your platform

- Who does this? Mid-level professionals, consultants, small organizations

Orchestrated Production (Team Coordination):

- Team of illustrators working from your direction

- Production crew executing your creative vision

- Development team building from your architecture

- Who does this? Senior professionals, established consultants, Spielberg

Institutional Apparatus (Layered Hierarchy):

- Creative team that anticipates your vision without direction

- Research assistants (servants) who handle “other duties as assigned”

- Departments that execute on strategic intent

- Who does this? Executives, tenured professors, oligarchs

AI-Augmented Individual:

- Prompt engineering to manifest specific operational knowledge

- Model configuration to match output to intent

- Curation and stewardship of generated content

- Who does this? Leading-edge practitioners in 2026

Here’s the strange part. We celebrate movement up this ladder. Going from primitive friction to skilled tool use is “getting better at your craft.” Going from individual work to directed labor is “growing your business.” Going from small team to orchestrated production is “scaling successfully.” Going from coordination to institutional apparatus is “reaching the top of your field.” I’m claiming the evaluation framework should focus on outcomes and responsibility, not protection of existing permission structures.

But when you jump from skilled tool use directly to AI-augmented individual, bypassing the entire labor-hiring ladder, people call it cheating. Even though the output can be identical. Even though the accountability is the same. Even though you’re taking full responsibility for what goes into the world. This is my operational lens, not universal truth. Other practitioners might map this differently based on their domains.

The only difference is you didn’t hire humans along the way. You used a different kind of amplification. One that doesn’t require institutional backing or departmental budgets or servant-assistant relationships.

And that threatens the permission structure. Because if an individual can produce institutional-quality outputs without building an institution, what does that say about all the layers we’ve built? What does it say about the gatekeeping we’ve accepted as necessary?

What Different Fields Call “Taking Responsibility”

I use the word “stewardship” because it fits my operational background, but different fields have their own language for the same concept:

Software developers call it “code ownership” or “accountability.” If your name is on the commit, you own what it does in production.

Academics call it “intellectual contribution” or “authorship criteria.” If your name is on the paper, you’re asserting you made a meaningful contribution to the ideas, not just the typing.

Military calls it “command responsibility.” If you’re in command, you’re responsible for the outcome, regardless of who executed the individual tasks.

Journalists call it “editorial responsibility” or “byline accountability.” If your name is on the article, you’re vouching for the accuracy and integrity of the content.

Architects call it “professional seal” or “certification.” When you stamp the drawings, you’re legally responsible for the structural integrity.

The language differs, but the core is the same: you put your name on it, you stand behind it, you’re accountable for what it does in the world. The question isn’t “did you personally execute every step?” The question is “can you defend the decisions that shaped this, and will you take responsibility for the outcome?”

The Real Standard

I think “making” happens when you can take that responsibility, whatever your field calls it. When you can defend why this needed to exist. When you can explain the decisions that shaped it. When you can stand behind what it does when someone else encounters it.

The CNC router didn’t make the B-24 sign. The illustrators didn’t make the storyboards. The AI didn’t make the doctrine. I made those things. The tools helped me manifest them faster, clearer, better. That’s what tools are for.

But I’m still figuring out where the line is. How much understanding do you need? How much distance is too much? How do we acknowledge displacement while still moving forward? I don’t have clean answers. Just operational experience and a growing sense that we’re asking the wrong evaluation questions.

If we’re going to evaluate the use of new technology, let’s evaluate it honestly. Is it producing better outcomes? Is it making individuals more capable? Is it transferring knowledge more effectively? Or are we just protecting the permission structure that says you need a team, a budget, and institutional backing before you’re allowed to amplify your own work?

Because right now, we’re celebrating the oligarchs with teams while questioning the practitioners with tools. We’re lauding the professors with research assistants (servants) while doubting the individuals with AI. We’re accepting Spielberg’s orchestrated production while rejecting the solo practitioner’s AI-augmented output. We’re calling corporate automation “progress” while calling individual AI use “cheating.”

And that says more about our evaluation framework than it does about the technology.

I can take responsibility for everything I’ve made. CNC-routed wood, illustration-assisted storyboards, AI-augmented doctrine. I know why each needed to exist. I can defend the decisions that shaped them. I stand behind what they do in the world. That’s my professional seal, my byline accountability, my command responsibility, my code ownership, my intellectual contribution.

Call it what you want in your field. The standard is the same. Not “how much friction did you endure?” Not “how many people did you hire?” But “can you take responsibility for what this does in the world?”

The woman in Corvallis couldn’t see that standard. She saw the tool as the work. In 2026, most people still can’t see it. They see the AI as the work, not the orchestration. They lack the decision altitude to distinguish between letting the model generate generic content and using the model to manifest specific knowledge that exists in your head but not yet in the world.

Maybe that distance will close. Maybe it won’t. But I’m not waiting for permission to use the tools that let me serve the mission. The Next Guy needs this knowledge. The tools that help me transfer it faster and clearer are just tools.

The making is in the manifestation. Always has been.

Last Updated on January 11, 2026