When You Become The Interface: A System “Tell” In Disguise

There is a quiet warning sign in complex systems.

You can see it in job descriptions that balloon until they no longer fit on one page. You can see it in calendars filled with both deep technical work and high level stakeholder meetings with no gap in between.

You can hear it in sentences like:

“I was in the datacenter server hall with earplugs in the morning, then briefing executives in the afternoon about the same system.”

Individually, those stories sound heroic. The person is versatile, trusted, indispensable.

Taken together, they describe something more troubling.

A human has become the interface.

When I worked as branch chief for iCAV, there were days that looked exactly like that. iCAV was sitting at Mount Weather as a temporary home. We knew it needed to move to a flagship data center at Stennis while keeping failover and service continuity.

On paper, many groups were involved.

- Data center staff at both sites

- Network and security teams

- ESRI and other vendors supporting lab environments

- External partners who consumed the system

- Executives who owned the risk and the budget

In practice, there were moments where one person became the path between them.

That person was often me.

I would spend part of the day in the data hall, earplugs in, configuring servers or Akamai settings because someone needed to do it and the team was stretched. Then I would drive to Washington, step into a briefing, and translate that configuration work into a risk narrative and timeline.

From the outside, it looked like dedication. From the inside, it was also a “tell” that indicated more investigation was needed.

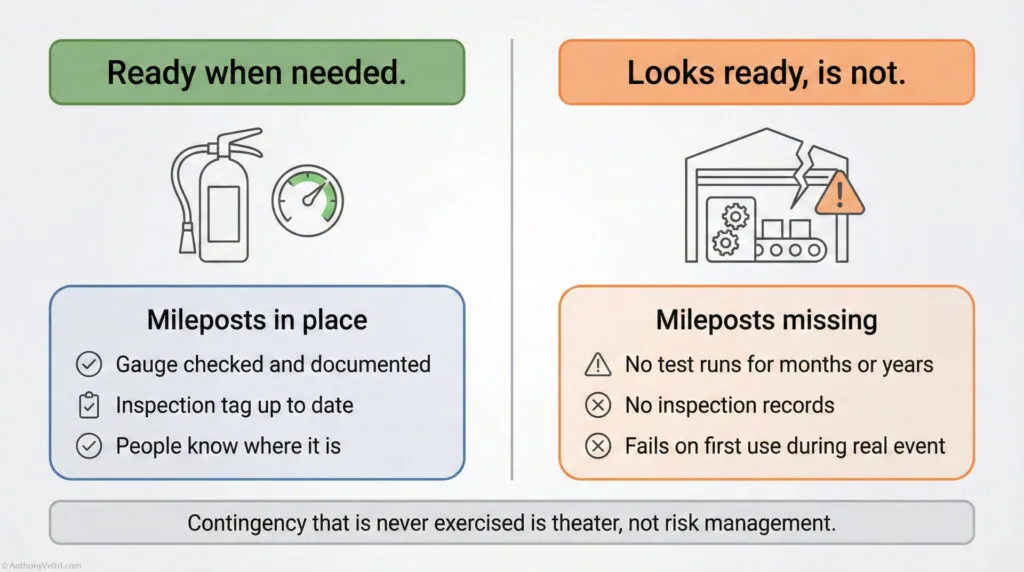

When humans become the primary interface between system components that should be linked by clear contracts, you get three problems at once.

- Fragility. If that person gets sick, burned out or leaves, the integration goes with them. Nobody else fully understands both sides.

- Opacity. Decisions that should be visible in code, contracts or diagrams are instead buried in one person’s head and calendar.

- Over-functioning. The person starts to carry more responsibility than their role supports. They begin to compensate for architectural gaps with personal effort.

The same pattern shows up outside of data centers.

- The analyst who manually reconciles two systems every week because integration was “postponed.”

- The project lead who becomes the translation layer between leadership that will not read details and engineers who do not see the mission.

- The community leader who has to bridge national level directives and the lived reality of their town, with no formal process to support them.

Sometimes this bridging is necessary in the short term. Systems do not refactor themselves overnight. People step up because they care.

The doctrine problem is when this becomes normal.

You know you are in that territory when:

- You are “too important to take a vacation” because there is no backup.

- You are constantly adjusting your own work to fit the gaps between tools or teams.

- Your title does not match the range of functions you quietly perform.

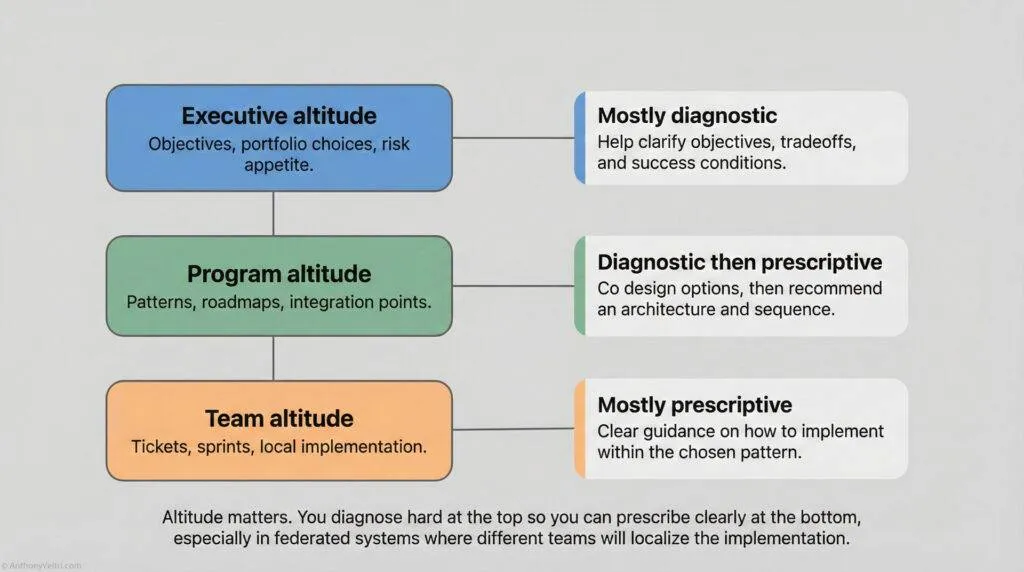

As an architect, I now treat “human as interface” as a diagnostic signal.

When I meet someone who seems to be everywhere at once, I do not just praise their stamina. I ask:

- What are you compensating for

- Where should there be a formal contract, pipeline or role that does not exist

- Which parts of what you do should be encoded into a system so that you can be replaced in that slice, even if you stay in the bigger mission

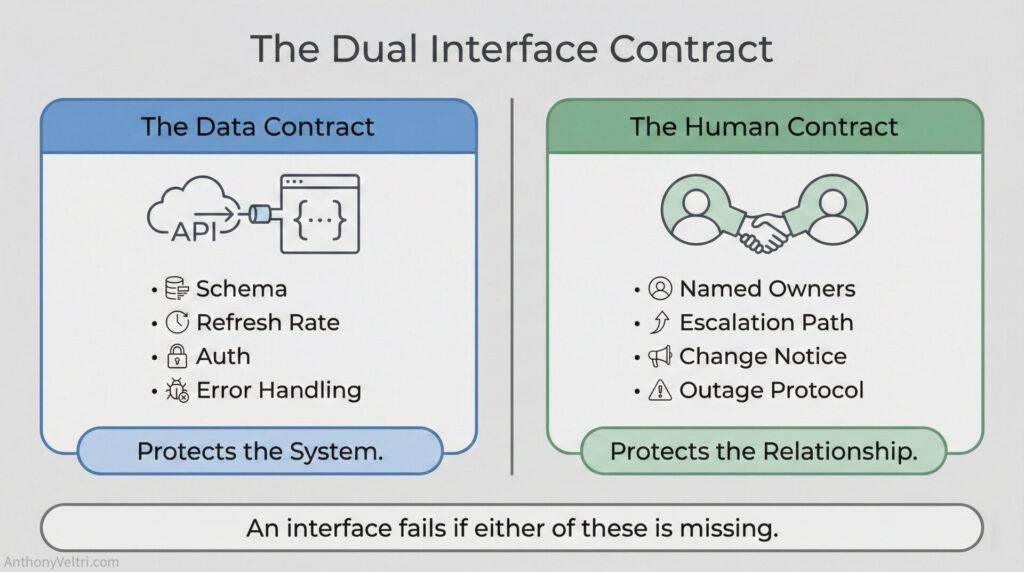

The fix is not to strip away responsibility from capable people. It is to turn hidden interfaces into explicit design.

That might look like:

- Defining a clear API between systems that currently only talk via manual export and import.

- Creating a documented playbook for a cross agency process that currently lives in one person’s memory.

- Establishing a second in command or rotation for a role that has become a single point of failure.

It also means setting boundaries.

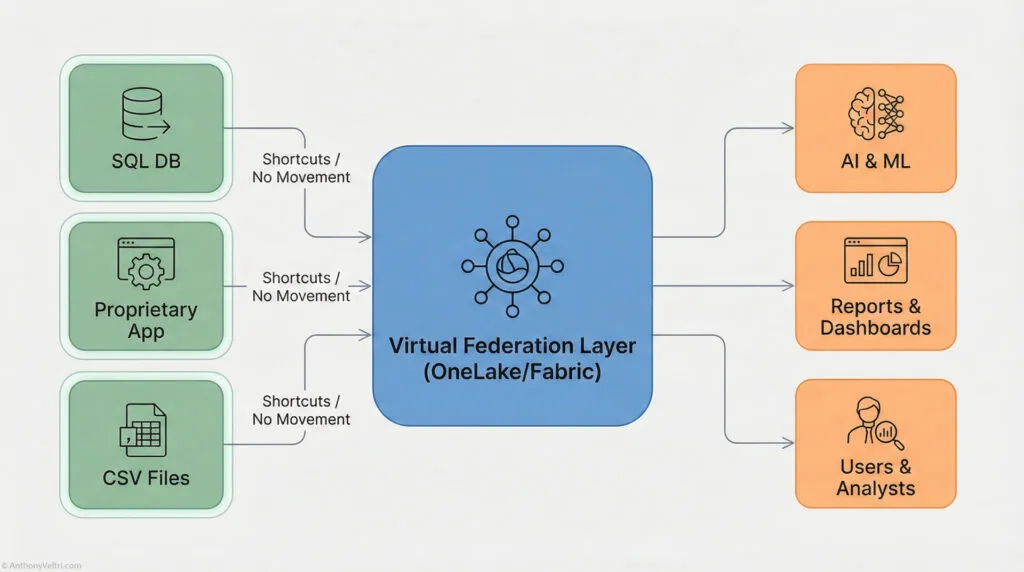

Golden Views over Federated Data: You don’t need to copy every sensor feed. You can build a “Virtual Federation Layer” (Center) that acts as the Golden View for the user, while the raw data stays where it is. Architectural Federation: Instead of forcing every partner into one database, we used a “Virtual Federation Layer” (Center) to connect disparate feeds (Left) without demanding they change their systems.

Virtual Federation: Instead of forcing migration, use a virtual layer (OneLake/Fabric) to connect disparate sources. The AI lives here, reading shortcuts rather than moving data.

There were times in my iCAV work where we overextended. We accepted DVDs in the mail, odd partner workflows and custom accommodations, because we wanted to be useful. That flexibility helped adoption, but it also risked turning the team into a permanent concierge layer.

At some point you have to say:

“We can help you shape your data, but we cannot change the number of seconds in a day so your uptime report looks better.”

That is a boundary. It protects system integrity and your own.

In my personal doctrine, “human as interface” is both a warning and an opportunity.

- As a warning, it tells you that your architecture has invisible joints held together by effort instead of design.

- As an opportunity, it tells you where the next layer of system improvement should go, because you can follow the stress lines in real people’s calendars.

If you recognize yourself in this description, you are not the problem. You are the instrument that reveals where the real problems live.

The work is to honor what you have been doing, then design and delegate so that the system no longer depends on you being in two rooms at once.

You should not have to choose between earplugs in the data hall and a briefing in the capital every day.

A healthy architecture knows how to carry its own messages.

During Hurricane Katrina deployment, our RF crew joked that we were turning ourselves into Yagi antennas. In this shot a teammate hams it up between the truck and the sky, but the joke hides a real systems tell: when the network is fragile enough that people start acting as the patch cables, you have turned humans into the interface.

Last Updated on December 9, 2025