When You Cannot Force Compliance: iCAV, Hurricane Katrina, And Lessons In Federation

When people talk about “federated systems,” it can sound abstract. In reality, federation is what you reach for when you cannot force anyone to do anything.

Before systems like iCAV matured, I saw the cost of non-federation up close (or rather, an integrated system trying to operate in a federated environment). During Hurricane Katrina, data lived in silos. Agencies guarded their information. Local leaders were overwhelmed. Everyone was working hard, but the picture never quite came together.

One memory still lives in my bones. A church parking lot in Bay St Louis, Mississippi had become a makeshift distribution hub. The high water mark on the church walls was about fifteen feet. You did not need a model to understand how much had been lost. Water seeks its own level. Fifteen feet inside meant fifteen feet everywhere.

A major relief organization arrived with trucks full of diapers, formula, ice and water. Their supplies were needed. Their attitude was not.

The parking lot was already full of donations that had come from other churches, local businesses and quiet networks that never show up in situation reports. The pastor and his volunteers had been sorting, improvising and rationing for days before the trucks rolled in.

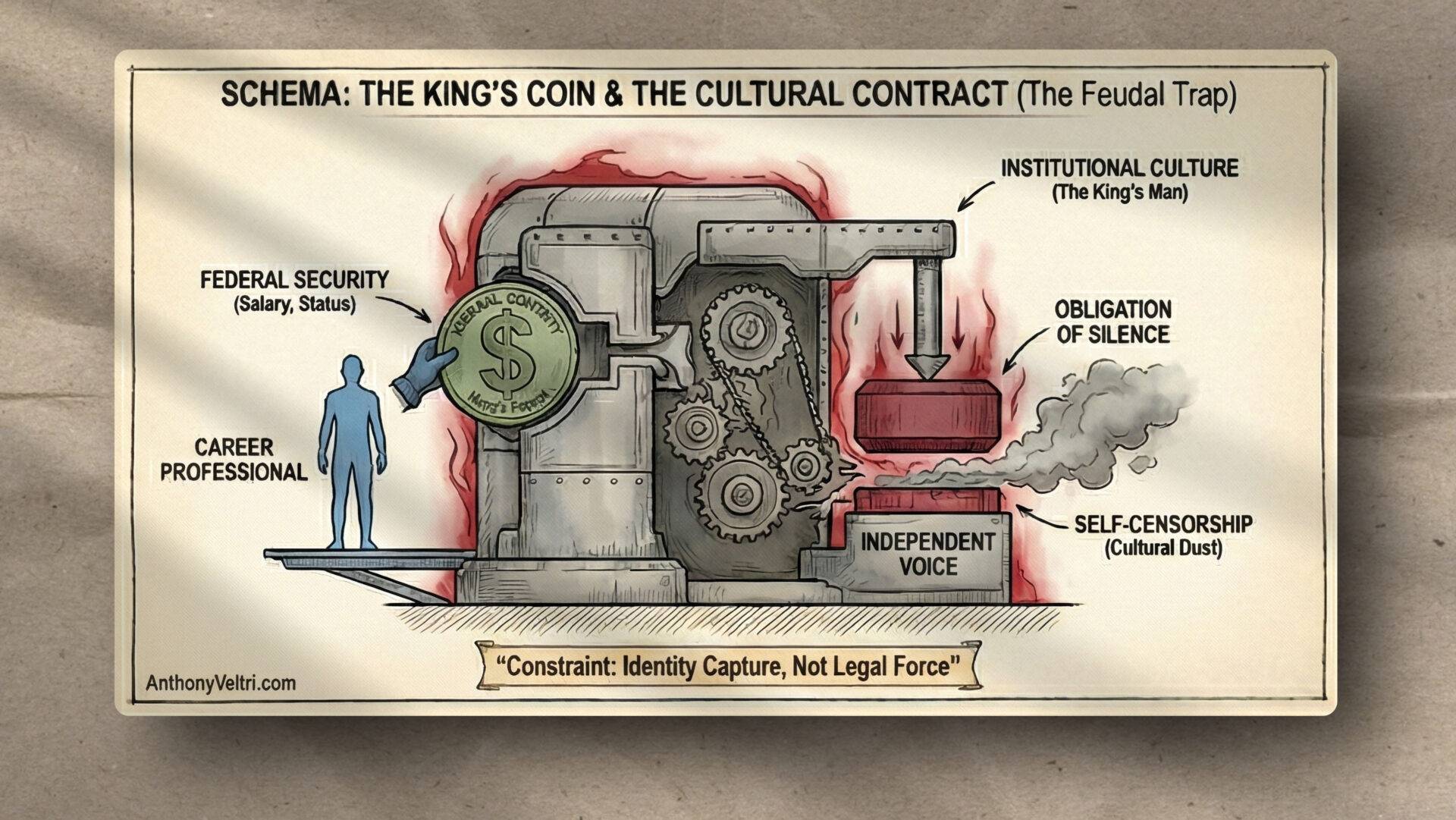

The organization was not content to manage the supplies they had brought. They wanted to manage all of it. Every pallet. Every case of water. Every box of clothes piled against the church wall. In their mental model, the moment their branded trucks touched the scene, the entire staging area should become a node in their system, under their procedures and their command.

They started demanding detailed information from the pastor and telling him how to run his community, as if the existing effort was just raw material waiting to be brought under proper management.

What they were really doing was behaving like an integrated system in a federated environment, and a poorly federated one at that. There were no pre-existing contracts, no shared task books, no agreed ownership of the overall operation. The community had its own patterns of trust and accountability that predated the disaster and would still be there long after the trucks left. The organization was trying to snap a rigid hierarchy onto a landscape that had never agreed to it.

That is the tension the pastor pushed back against in a single sentence that I will never forget:

“We appreciate and need your supplies. What we do not need is your management of a reality you only understand on paper. We can make your resources go further if we work as partners, not in a master and servant relationship.”

That is federation in human terms. The community will accept help, but not at the expense of sovereignty.

It also exposes a hard truth about disasters.

A disaster staging area is the worst possible time to begin building relationships. If that is where you start, you are already behind. People will still find ways to work together, but the cost is higher and the friction is visible in every conversation.

You feel it when an outsider arrives with clipboards and doctrine that never touched the ground before landfall. You feel it when local leaders have to defend their own legitimacy in the middle of a crisis. The pastor in Bay St Louis was doing real-time boundary work. He was accepting aid while defending sovereignty because the pre-existing relationship simply was not there.

Later, when I served as branch chief for the iCAV program at DHS, that lesson was never far away. iCAV pulled together data about the 19 critical infrastructure and key resource sectors at the time. Finance. Transportation. Power. And so on. Our partners included federal agencies, tribal nations and local municipalities. Each had different update tempos, data quality and program maturity. Some followed our suggested refresh rates. Others updated intermittently, on their own schedule, for their own reasons.

Further Reading: The iCAV architecture evolved into the DHS Geospatial Information Infrastructure (GII) and OneView, which became the DHS CIO-designated standard serving 296,000+ eligible users across all 22 DHS components and state & local partners via the HSIN network. The two-lane approach and federation patterns established during the 2008-2010 development period survived the technology transition and continue in the current system. For comprehensive system history, see Annex K: iCAV to GII/OneView Architecture.

We could not force them to comply. Sometimes law and policy prevented it. Sometimes trust and history did.

So much later, we built iCAV as a truly federated system. We:

- Decoupled data from any single application.

- Designed ingestion and synchronization layers that could tolerate different tempos and formats.

- Accepted that some parts of the map would always be “less fresh” than others, and made that visible instead of pretending otherwise.

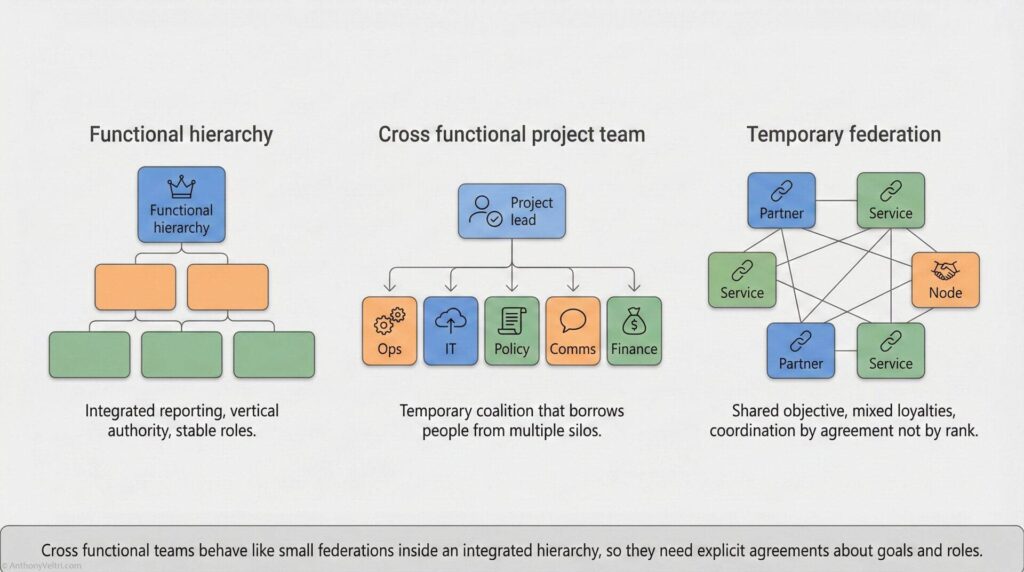

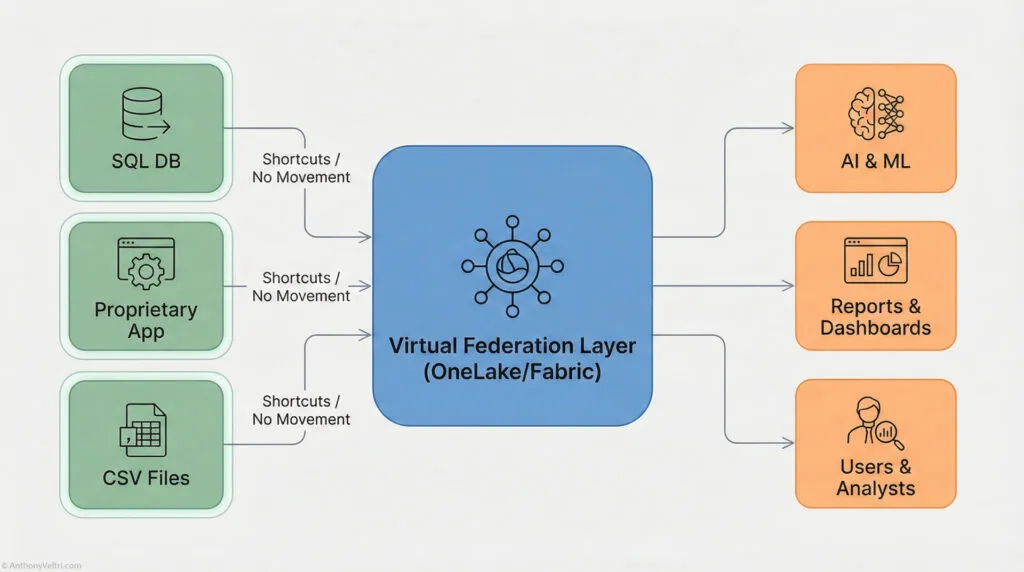

Golden Views over Federated Data: You don’t need to copy every sensor feed. You can build a “Virtual Federation Layer” (Center) that acts as the Golden View for the user, while the raw data stays where it is. Architectural Federation: Instead of forcing every partner into one database, we used a “Virtual Federation Layer” (Center) to connect disparate feeds (Left) without demanding they change their systems.

My daily reality swung between earplugs in the data hall at Mount Weather, configuring servers and Akamai components, and suit and tie briefings in Washington, explaining to executives what the system could and could not do. We later moved iCAV to a flagship data center at Stennis, keeping failover at Mount Weather, and kept that federated posture through the transition.

Along the way, we drew lines. We accepted data on DVDs. We supported awkward partner workflows because the mission justified it. But when a partner asked us to change the number of seconds in a day to make their uptime statistics look better, I said no. We could explain maintenance windows and context, but we would not alter reality for a metric.

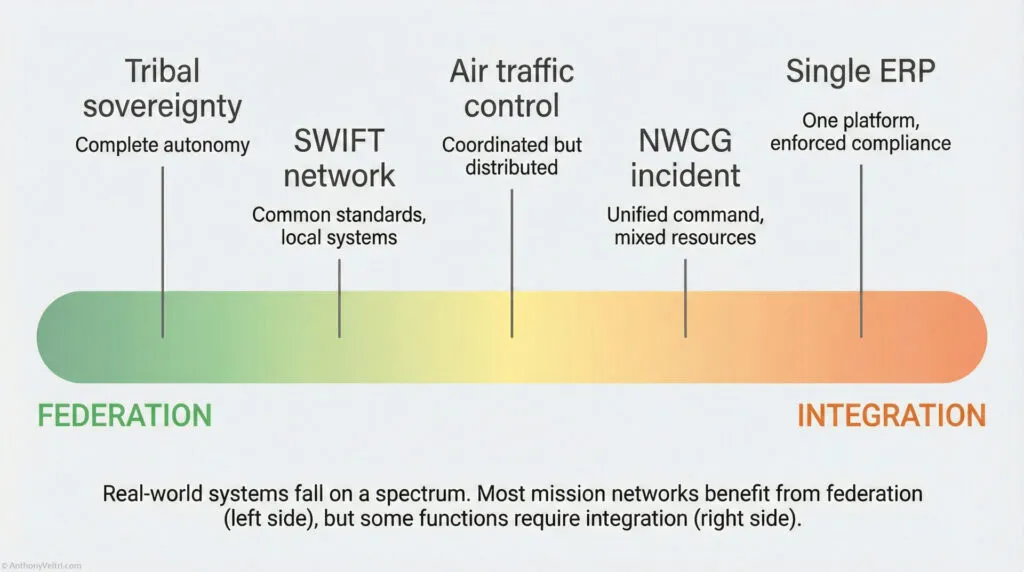

That is one side of the spectrum. Federation when you cannot force compliance, where sovereignty and uneven maturity are hard constraints.

There is another side.

What It Looks Like When Commitment Comes First

The fire system sits in the middle of the spectrum: “Coordinated but Distributed” just like Air Traffic Control. It balances local sovereignty with national power. The Spectrum of Consent: Most disasters require Federation (Left) because sovereignty is high. Wildland Fire can move toward Integration (Right/Middle) because agencies have pre-committed to shared standards (NWCG).

The Lesson: Successful systems are often integrated locally (for control) but federated globally (for scale). Respecting Sovereignty: In a disaster, you cannot force Integration (Right). You must accept Federation (Left) because local sovereignty is a constraint you cannot wish away.

In the wildland fire community, particularly through the National Wildfire Coordinating Group and the Incident Command System, you see something almost unique in the civilian federal world.

There is a level of pre-existing commitment and shared doctrine that makes true integration possible in a narrow, high-stakes domain.

If you want to work as a dispatcher, a radio operator, a crew boss, a Sawyer, a helicopter manager, or even an Incident Commander, you do not just watch a training video and click “I agree.” You get a task book.

That task book lists real tasks you must perform and have observed. Often on a live incident. Often signed by someone who already holds the qualification you are pursuing.

People are proud of those task books. They chase signatures not because they love paperwork, but because each line means they have done the work in the real world and earned the trust of their peers.

The result is swappability in crisis that almost no other civilian part of the federal government can match.

An Incident Commander can hand off at the end of an operational period to another IC from an entirely different agency. With a proper briefing, that person can step into the role and continue. The role is not “the person who happens to be in charge.” It is a shared protocol with clear expectations and boundaries.

Systems like IRWIN and ROSS reflect the same spirit. Agencies that are normally federated and quite different in their home business voluntarily conform to common standards for incident records and resource ordering.

On a fire, they align file naming conventions, data schemas, reporting cadence and contracting practices. They fly aircraft and log thermal imaging data in ways that match the shared protocol. Back home they may go back to their own flavors. In this narrow domain, they agree to integrate.

The key is timing.

That commitment is built before the disaster. In classrooms. On smaller incidents. During off season exercises. In the long, quiet work of task books and doctrine development.

By the time you are on a complex fire, you are not negotiating whether an Incident Commander has the authority implied by the vest they are wearing. The relationship between the role and the system has been drawn already.

If the Katrina pastor had a pre-existing, trusted doctrine and task book like that with the relief organization, the conversation in the parking lot would have been different. The supplies would still be welcome. The sovereignty would still matter. But the negotiation about “who actually runs this” would have been anchored in shared expectations, not improvised under flood lights.

Two Pillars Of Federation, And A Hint Of Integration

Federation, in my doctrine, still has two pillars.

- Respect sovereignty and uneven maturity. You design interfaces and contracts that let partners contribute without erasing their identity or constraints.

- Do not lie about the picture. You accept and expose uneven freshness or quality instead of hiding it behind pretty graphics.

The wildland fire example adds a third insight.

- Where you can commit early and deeply, you can afford tighter integration later. Task books, doctrine and shared standards are forms of pre-committed federation that make limited integration possible when lives are on the line.

For alliances, coalitions and large federated institutions, this pattern matters.

You will always have partners with different politics, budgets and technical baselines. You cannot integrate your way out of sovereignty. Most of the time you will need true federation built on respect and honest representation of reality.

Sometimes, in narrow domains where the mission justifies it and the commitment is real, you can do what NWCG does. You can agree in advance to behave as one system in that slice of the world.

The crucial point is to know which world you are in.

- In the church parking lot, you are in emergency federation with no pre-existing trust. You must behave accordingly.

- In a wildland fire camp, with task books and ICS roles, you are standing on years of pre-committed doctrine. You can afford tighter integration because people chose it long before the smoke column went up.

Good architecture is not choosing one pattern forever. It is knowing when you are dealing with forced federation, voluntary integration, or something in between, and then designing your systems and your relationships to match.

Last Updated on January 31, 2026