Disaster Response Staging Areas Are The Wrong Time To Start Trust

Staging areas are where you execute, not where you invent trust.

When partners first meet in the parking lot of a disaster, they bring trucks, supplies, clipboards and logos. What they usually do not bring is a shared playbook.

The pattern is simple:

- Build trust, doctrine and expectations before you need them

- Use exercises, agreements and task book style practices to bake in the relationship

- Walk into the staging area ready to execute a known pattern, not negotiate your existence under flood lights

What happened at a small church in Bay St Louis during Hurricane Katrina is the negative example. What happens in wildland fire camps under NWCG and ICS is the positive example.

The Parking Lot In Bay St Louis

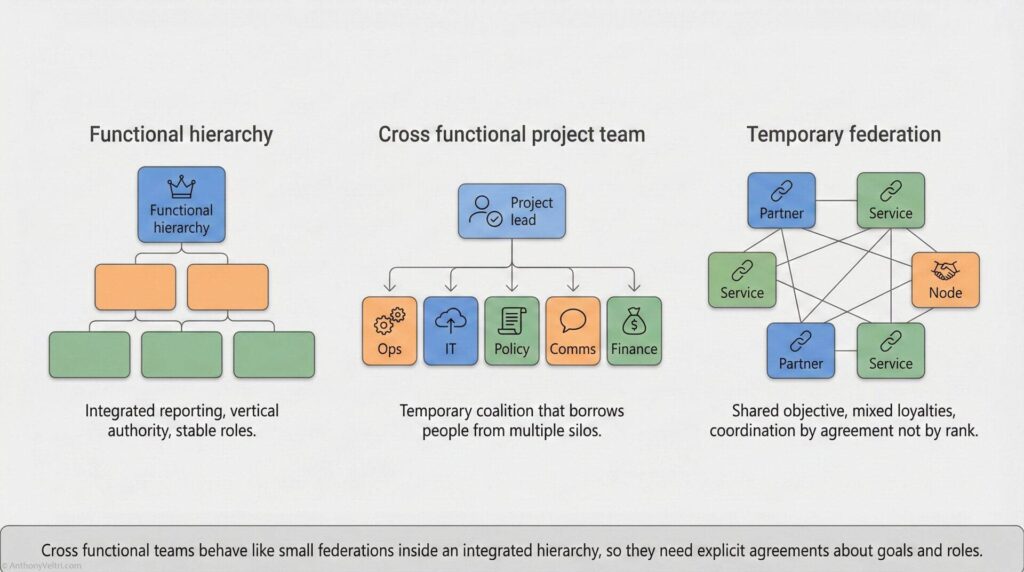

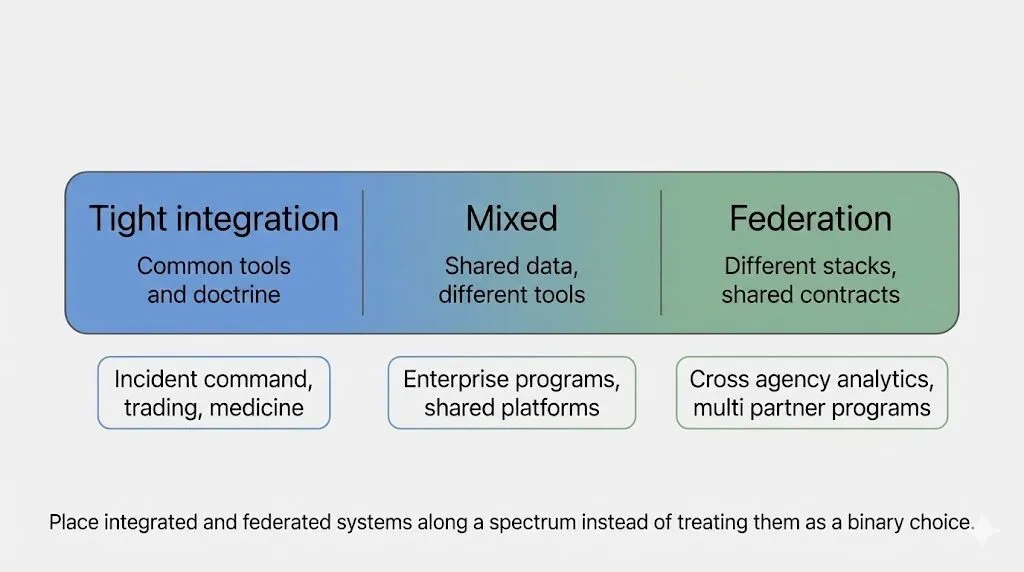

The Staging Area Reality:A disaster response isn’t a Hierarchy (Left); it’s a Temporary Federation (Right). You are just one node connecting to other sovereign nodes. You don’t own the org chart.

When I first walked onto the grounds in Bay St Louis, one of the first things I noticed was the high water mark on the church walls.

About fifteen feet up.

You do not need a model to understand what that means. Water seeks its own level. Fifteen feet inside is fifteen feet over everything that used to be there.

By the time we arrived, the church parking lot had become a makeshift distribution hub. Not because a national organization declared it so, but because the community did. People brought:

- Diapers, formula, food

- Bottled water and ice

- Clothes and basic supplies

The pastor and volunteers were already sorting, improvising and rationing. They knew who lived where, who had lost everything, who had relatives out of town, whose truck still ran, which roads were passable.

Then a major relief organization arrived.

Trucks, logos, clipboards, procedures.

Their supplies were needed. Their attitude was not.

They did not just want to manage the pallets they had brought. They wanted to manage all supplies on site:

- Everything that had arrived from local churches

- Everything stacked against the church wall

- Everything that had already been staged by the community

In their mental model, once their branded trucks touched the scene, the parking lot became a node in their system, under their procedures and command.

They immediately started:

- Demanding detailed information from the pastor

- Telling him how to run his community

- Treating existing local effort as raw material waiting for proper management

From the outside, it might have looked like they were bringing order. From the inside, they were trying to overwrite a living system that had already adapted.

The pastor’s response cut through all of it:

“We appreciate and need your supplies. What we do not need is your management of a reality you only understand on paper. We can make your resources go further if we work as partners, not in a master and servant relationship.”

That sentence is a sovereignty boundary.

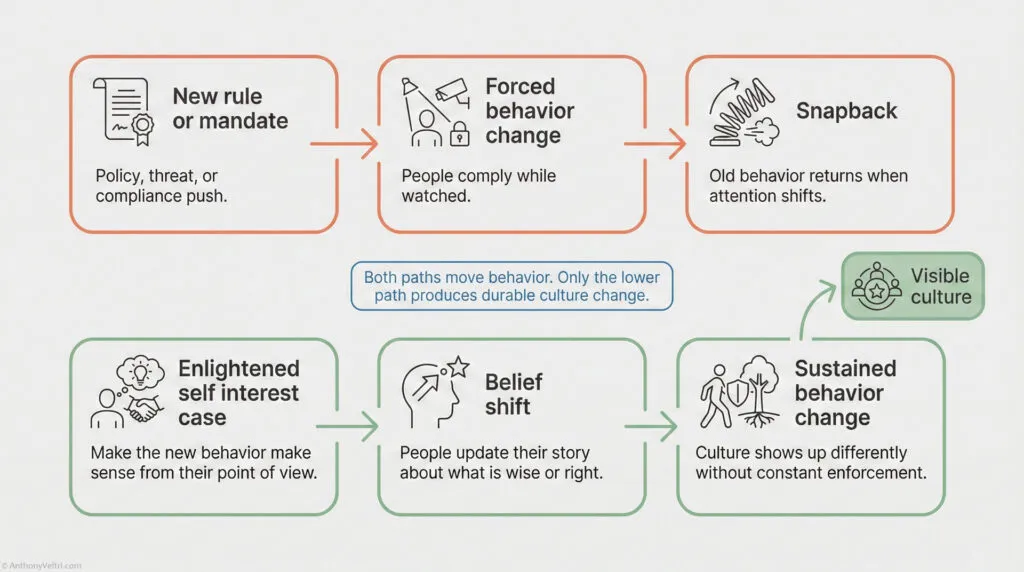

It is also a textbook example of this pattern:

- Trust did not exist before

- The relationship was being negotiated in the staging area itself

- A national integrated system was trying to snap itself onto a federated reality that had never agreed to its rules

It “worked” in the sense that people eventually got help. It failed as a model for repeatable, respectful coordination.

I have photographs of that parking lot, that church, and those faces. They are reminders that this is not theory. It is a real pattern with real people in the middle of it.

What Wildland Fire Gets Right

Now contrast that parking lot with a wildland fire camp.

When engines, crews, helicopters and overhead arrive, they are also gathering into a staging area. The difference is in what they bring along that is not visible on a truck manifest.

They bring doctrine.

- NWCG standards

- ICS roles and vocabulary

- Task books that encode competence and commitment

- Shared training and pre season exercises

If you want to be a dispatcher, a radio operator, a Sawyer, a crew boss, a helicopter base manager, or an Incident Commander, you do not just sit through a slideshow.

You carry a task book.

The task book defines real tasks that you must perform under observation. Qualified peers sign off. The signatures are a social and technical contract that says:

- “This person has done this job under real conditions.”

- “I am willing to stake my name on their competence.”

By the time you hit a large incident:

- You already know what “Logistics” means

- You already know how an operational briefing runs

- You already know what a resource order will look like

- You already know that an IC vest means specific authority and responsibility

You are not inventing the relationship in the parking lot. You are exercising it.

That does not mean there are no disagreements or friction. But the baseline is entirely different.

Wildland fire is what it looks like when:

- Trust and expectations are built over years

- Commitment is encoded as ritual

- The staging area is the place where you execute a known playbook

Bay St Louis is what it looks like when:

- A national system arrives in integrated mode

- The local system has never agreed to that integration

- Trust and control get fought out on bare pavement with people watching

The doctrine point is not that every environment can become NWCG. It is that you notice which world you are in and behave accordingly.

Integrated Systems In Federated Environments

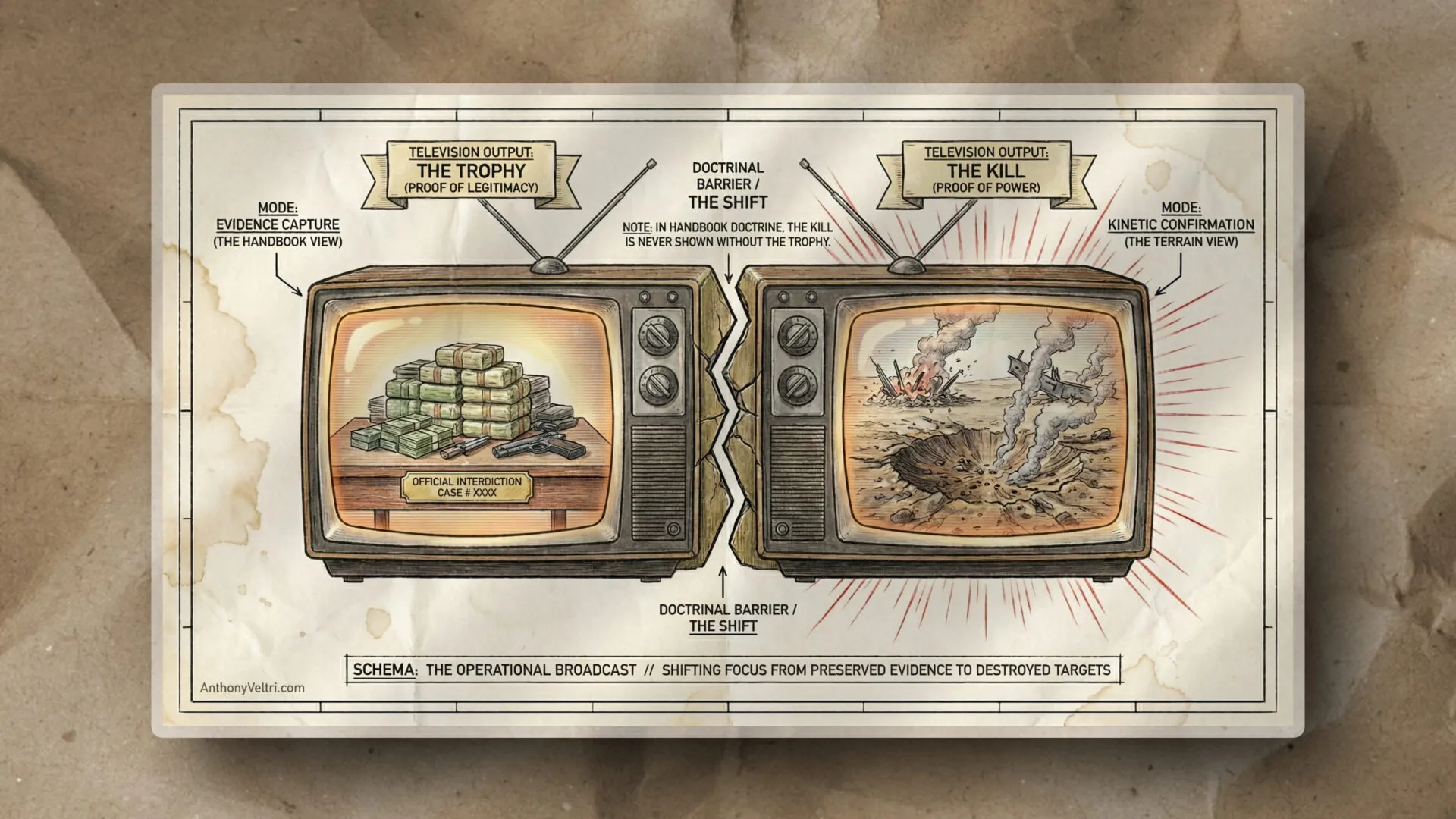

The relief organization in Bay St Louis was behaving like a fully integrated system.

Inside their own walls, that probably works:

- Centralized rules

- Standard operating procedures

- Clear org chart and command structure

But the church parking lot is a federated environment:

- The church is its own sovereign node

- Local networks have their own authority and knowledge

- Donors and volunteers do not report to the national org

There were no pre existing contracts.

- No MOU that said “this is how we work together if a storm hits”

- No joint exercises

- No agreed process for transfer of authority over a staging area

They were trying to play an integration game on a board that had never accepted that game.

The same thing happens in technical systems when:

- A centralized platform assumes other teams will automatically adopt its standards

- Federated partners are treated as if they were internal departments

- Interfaces are designed as if everyone had already agreed to them

The pastor’s line is the human equivalent of an interface error.

“We appreciate and need your supplies. What we do not need is your management of a reality you only understand on paper.”

The pattern here is to recognize that:

- In many environments, you cannot force compliance

- You cannot start by claiming authority over everything on site

- You must negotiate, slowly, from a stance of partnership and respect

And if you know you will face that kind of environment often, you should start building relationships before the storm hits.

How To Pre Build Trust Before The Staging Area

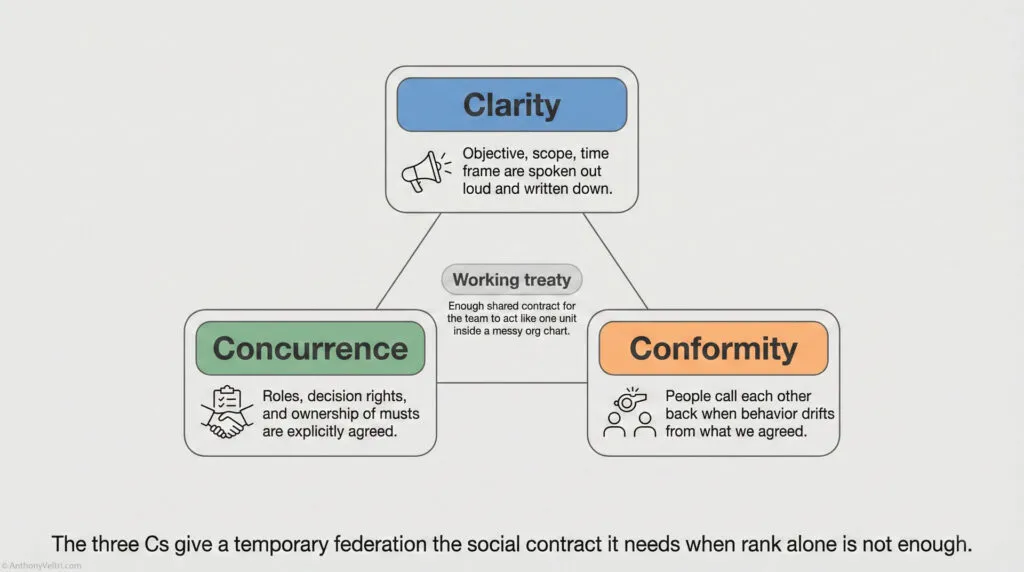

If you accept this pattern, the next question is practical:

What do you actually do before the crisis so you are not improvising in the parking lot?

Here is a concrete checklist.

1. Map the real local authorities, not just the org chart

- Identify pastors, tribal leaders, local emergency managers, school principals, NGOs and business owners who are actually trusted

- Recognize that some of them will not have formal titles

2. Establish human contact in calm weather

- Visit in person if possible

- Share a meal, walk the space, listen more than you talk

- Ask “If something bad happened here, what would you want from us, and what would you never accept”

3. Capture simple, written expectations

Keep it small and human readable:

- What you will bring

- What you will never try to control

- What joint decision making looks like

- How you will handle disputes during stress

This can be an MOU, a letter of intent, or even a one page agreement. The point is clarity, not legal formality.

4. Run low stakes exercises

- Tabletop exercises with local leaders

- Communications tests

- Joint small incidents as practice

These are the human equivalent of unit tests.

5. Agree on visible symbols

- Who wears what

- Who speaks at briefings

- What vest or badge means “final call” on specific decisions

In wildland fire, things like an IC vest and ICS position titles carry meaning because they have been earned and recognized. You want smaller versions of that in your environment.

Beyond Disasters: Where This Pattern Shows Up Everywhere

Although this story is rooted in Katrina, the pattern shows up far beyond hurricanes and fires.

Alliance operations (NATO, EU, coalitions)

If the first time you meet a partner’s tech or ops team is on day one of a crisis, expect Bay St Louis behavior. Build doctrine and data contracts before the pressure spike.

Large vendors and small clients

When a vendor walks into a customer site and tries to impose “how we do things here” on a living culture, the same friction shows up. Pre work matters.

Internal programs and front line units

Headquarters often behaves like the relief organization. Field units often feel like the church. The staging area might be an email chain or a project kickoff, but the dynamics are identical.

Any time you see a powerful, integrated system trying to snap itself onto a federated reality, ask:

- Have we already invested in trust and expectations here

- Or are we trying to start trust in the staging area

If it is the latter, slow down and change tactics.

A Personal Note And An Invitation To Reflect

I wrote about these days in my book Katrina, A Journey of Hope. I still have the photographs of that church, the watermark on the walls and the parking lot full of supplies and people.

When I think about doctrine now, I do not see clean diagrams first. I see that pastor, those volunteers and that clash between an integrated system and a federated reality.

If you have ever been the person in the parking lot, ask yourself:

- Where in my world am I still trying to start trust in the staging area

- What can I do this month to build even one relationship ahead of time

And if you are on the side with the trucks and logos:

- How can you arrive as a partner who respects sovereignty, not as a master looking for a new node in your system

That is the heart of this doctrine in practice.

Last Updated on January 17, 2026