Living With Incomplete Pictures: Notes From High Tempo Systems

If you are responsible for a high-tempo mission system, especially one that spans nations and organizations, what are you actually hiring for when you put someone in charge of the technology stack

You are not hiring a gadget person. You are hiring someone who can live with incomplete pictures, uneven partners and unforgiving timelines, and still keep the system honest and useful.

Lately I have been looking back at my career through a particular lens. Most of my life has been training for that, long before I had language for it.

When People Die On The Latency Budget

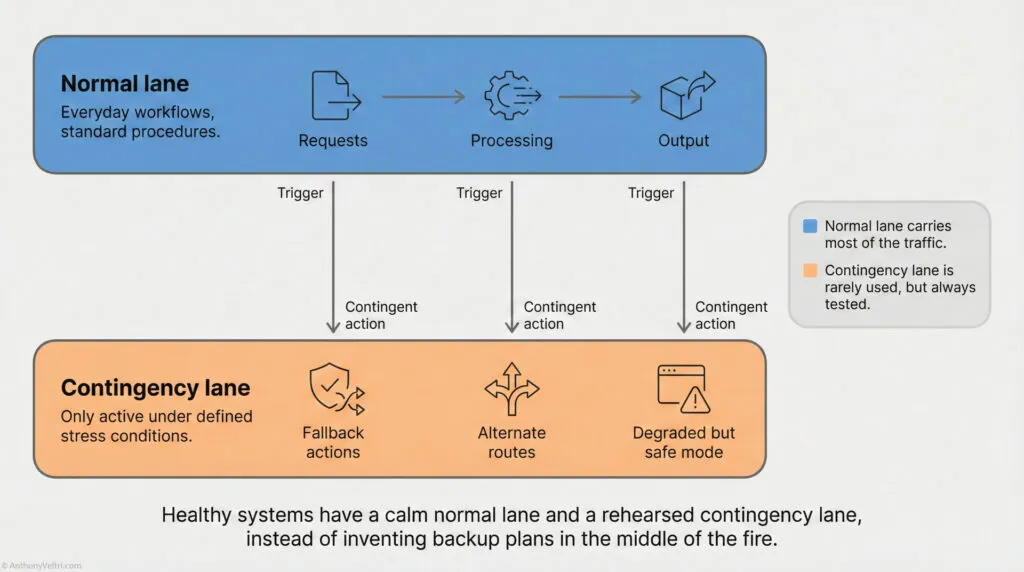

Architectural Slack: Designing for the “Legal Limit” creates a Single Lane system. Respecting the envelope means building a “Contingency Lane” (Orange) so you have space to maneuver when the weather turns. Shifting Lanes: When the air (or other circumstances) turns against you, you leave the “Normal Lane” (Efficiency) and enter the “Contingency Lane” (Survival). You cannot fly a “Blue Lane” mission in “Orange Lane” weather. The Reality of Operations: In high-tempo systems, the “Normal Lane” (Perfect Data) is often blocked. You must design the “Contingency Lane” (Partial Truth) to keep the mission moving.

In some systems, latency is an annoyance.

In others, people die on the latency budget.

During large incidents, whether it was a hurricane, a major security event or a complex wildfire, there was always this quiet pressure in the background:

- Information never arrived all at once

- Feeds updated at different tempos

- Some partners were live, others were on a delay, some were essentially frozen

Executives would ask a simple question.

- “Where is the risk right now”

- “Where are our assets”

- “What do we know about this target or this fire”

They wanted a clean, fused picture. The reality was always a mosaic.

In one sense, every high-tempo mission system is an air picture. You are constantly juggling:

- Multiple sensors with different ranges and blind spots

- Platforms that appear and disappear

- Feeds that obey different clocks

- Partners that own their own data, policies and caveats

The job is not to pretend that you have a perfect picture. The job is to decide, in real time, what is good enough to act on and what must be held back.

That is a very different mindset from “let us build the perfect database.”

The First Time I Realized The Picture Would Never Be Clean

One of my early shocks came working on a national geospatial viewer that fed decision makers during crises and special events.

On paper, it sounded simple.

- Build a single place where senior leaders can see incidents, assets and critical infrastructure

- Ingest data from many partners

- Show a map that everyone can trust

In practice, it felt like trying to build a real time air picture from sensors that did not agree on what sky even meant.

Some partners had beautiful, well maintained data that updated regularly.

Others sent DVDs in the mail.

Some had strict change control and documented schemas.

Others had one person, three spreadsheets and heroic intent.

We had to accept that, at any given moment:

- Parts of the map were “fresher” than others

- Some symbols were essentially hand drawn

- Some feeds would drop mid incident and come back with a different structure

You can treat that as an embarrassment and hide it, or you can treat it as a design constraint and surface it.

We chose the second path as much as we could.

That experience shaped how I think about any mission system where the cost of waiting for perfect information is higher than the cost of acting on incomplete truth.

It also maps very cleanly to coalition environments where each nation controls its own sensors, networks and caveats.

You will never get everyone on the same schedule. You have to design for useful interoperability, not perfect uniformity.

Earplugs In The Server Rooms at the Data Hall, Jacket In The Briefing Room

Another lesson came from the role I played on that same system.

In theory, there should have been:

- Architects

- Engineers

- Operators

- Briefers

All with clean handoffs.

In reality, there were weeks where my day looked like this:

- Morning in the data hall with earplugs in, configuring servers, tuning caches and working through change control with hosting staff

- Afternoon in a briefing room with a jacket on, explaining to senior leaders what the system could do, what had changed, and where the real risk and limitations were

I was the human interface between:

- Deep technical details

- Operational users

- Stakeholders who had veto power but no time

That is fun the first few times, then you realize it is also a system smell.

Whenever the same person is the only bridge between operators and engineers, or between different security domains, or between national providers and a combined picture, it tells you something about the architecture:

- Interfaces are not mature yet

- Contracts are incomplete

- Roles are not fully defined

The answer is not to clap for the hero who can be in every room. The answer is to design the system so that you do not need a hero to keep it coherent.

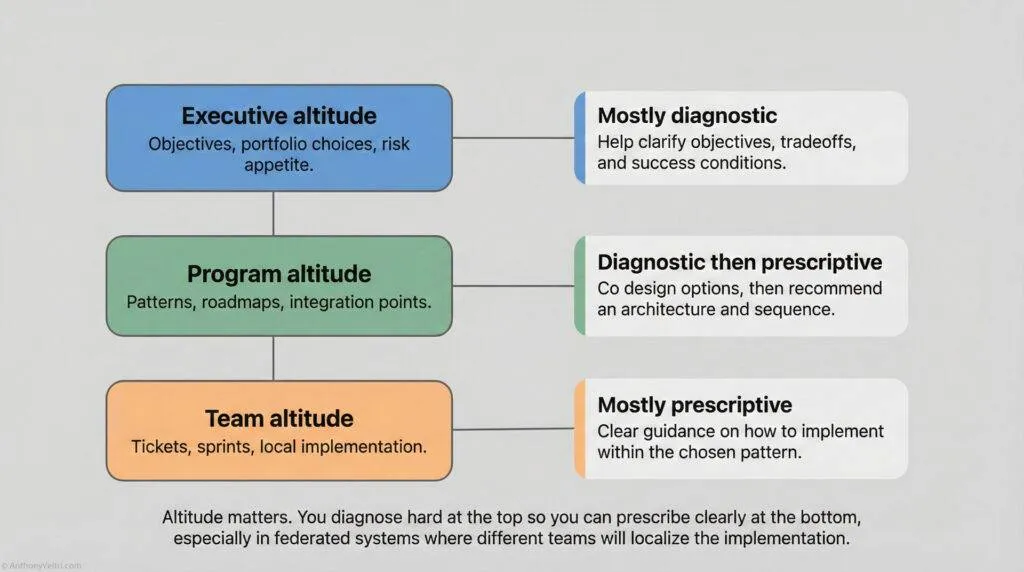

In a high tempo mission network, that looks like:

- Clear interface ownership between feeds

- Published data contracts and caveats

- Decision altitudes that match the information level

Otherwise the “principal technologist” becomes a bottleneck instead of a force multiplier.

Federation Is Not An Aesthetic Choice

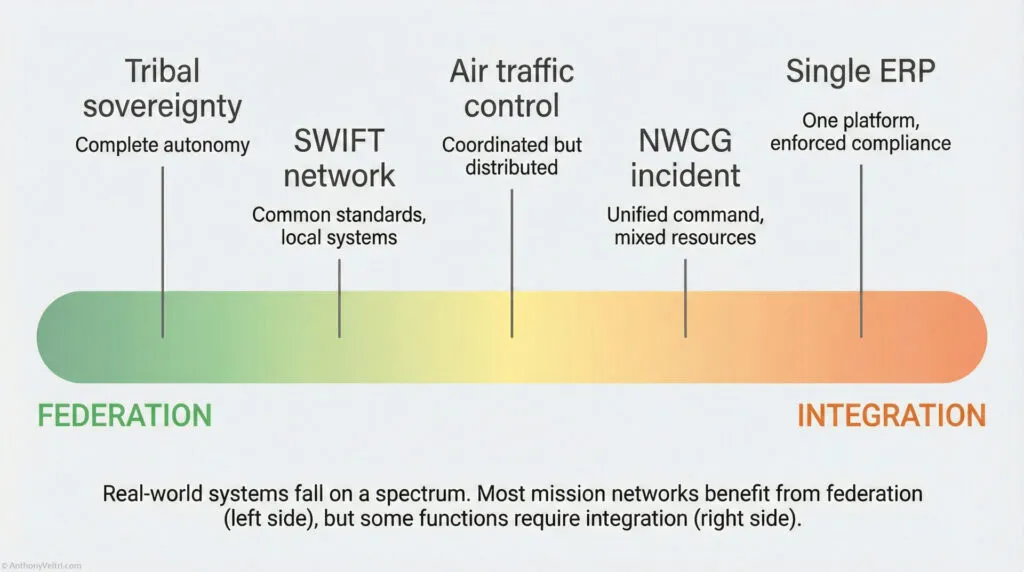

The fire system sits in the middle of the spectrum: “Coordinated but Distributed” just like Air Traffic Control. It balances local sovereignty with national power.

Respecting Sovereignty: In a disaster, you cannot force Integration (Right). You must accept Federation (Left) because local sovereignty is a constraint you cannot wish away. The Lesson: Successful systems are often integrated locally (for control) but federated globally (for scale).

It took disasters for me to understand federation as something deeper than an architectural buzzword.

In Katrina and later events, I watched what happens when a big, integrated system tries to override local sovereignty in the middle of a crisis.

It never goes well.

Local leaders know their people and their geography. They have built trust over years. You cannot just show up with trucks, clipboards and a logo and expect to take command of their reality.

They may accept your resources. They will not accept invisible control.

In technical terms, a church parking lot that becomes a distribution hub is a federated node. It has its own authority, policies and social graph. It is not a blank canvas waiting for a national workflow engine.

The same thing is true when you connect national systems into a shared mission network.

Each partner wants to:

- Preserve sovereignty over its own data

- Maintain its own caveats and constraints

- Be a peer in the decision process, not a downstream consumer

That has consequences:

- You cannot design as if you own every sensor and system

- You cannot assume that everyone will adopt your schema

- You cannot bury caveats in a footnote and call it good

Federation is not an aesthetic choice. In coalition environments it is reality.

The job is to design for honest federation and only tighten integration in narrow slices where the mission justifies the cost.

What Wildland Fire Taught Me About Pre-Commitment

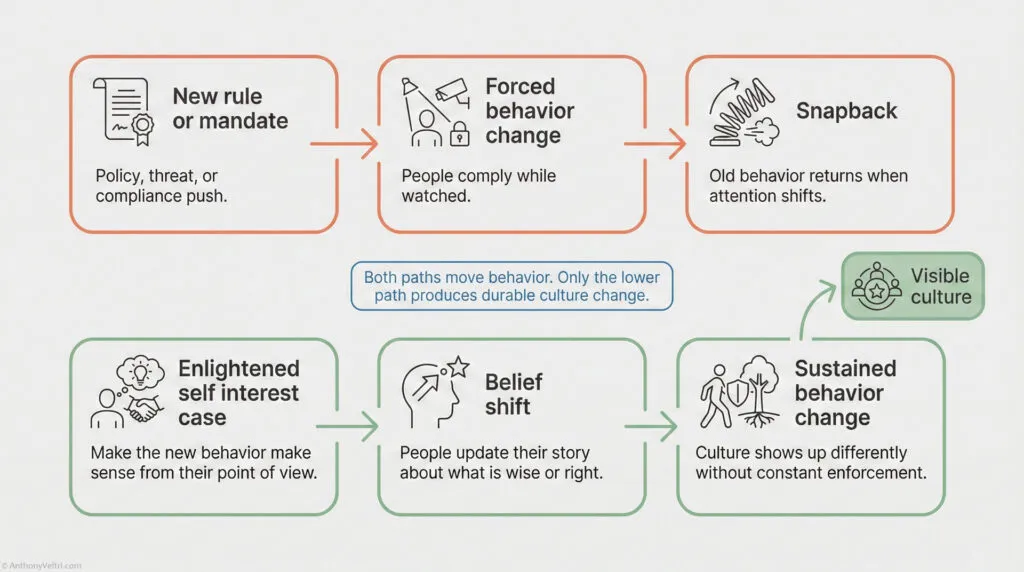

Pre-Commitment: Wildland fire works because agencies pre-commit to a shared doctrine (Bottom Path). They don’t try to negotiate rules in the smoke; they rely on the “Working Treaty” they signed when the sky was clear.

Wildland fire looks chaotic from the outside.

Inside a well run incident, it is anything but.

By the time people arrive at a large fire, they share:

- NWCG standards

- ICS language

- Task books that represent real, observed competence

Two things matter here.

First, roles are defined as protocols, not personalities. An Incident Commander is not “whoever seems in charge.” It is a qualified role, backed by a history of training and signatures.

Second, the relationship between agencies is pre committed.

Forest Service, BLM, Park Service, state crews, contractors, aviation resources. They all come from different organizations, but when they are on the fire, they are operating on a shared doctrine by choice.

They have decided ahead of time where they will standardize and where they will remain different.

You do not negotiate that in the smoke.

That is exactly how you have to think about any complex, multi national mission system:

- Where do we accept full diversity and federate

- Where do we create golden datasets or shared codes

- What rituals prove commitment and competence

If you answer those questions when the sky is clear, the staging area becomes execution. If you ignore them, the staging area becomes a power struggle.

Documenting My Life Through This Lens

When I look back now, almost every chapter of my career answers the same set of questions in different clothing:

- How do you keep a picture honest when every feed lies a little, and at a different tempo

- How do you respect sovereignty while still producing a shared view of reality

- How do you encode commitment in rituals and task books instead of treating it as a speech

- How do you keep humans in the loop where they matter, without forcing them to be manual glue between brittle systems

Hurricanes, wildfires, national geospatial programs, federal registers, international work on infrastructure and flood risk. All of them were laboratories for those problems.

That is the lens I bring to any high tempo mission network where lives, aircraft, sensors and politics share the same sky.

If you operate in that kind of world, it might be worth asking yourself:

- Where am I still pretending I can force compliance, when I am actually in a federated environment

- Where am I relying on a hero to bridge systems that should be talking directly

- Where am I trying to start trust in the staging area instead of building it now

Those are the places where doctrine stops being words on a page and starts being the difference between friction and flow, between confusion and a usable picture of the world, even when that picture is never quite complete.

Last Updated on December 9, 2025