Stranded in Vienna, Responsible in Kyiv

A field note on responsibility outrunning authority when the system breaks and the mission does not.

In April 2010, the Iceland ash cloud grounded flights across Europe. It also turned a routine civil-military engagement into a test of whether I could actually deliver when the system fell apart.

This page is a Doctrine Guide. It shows how to apply one principle from the Doctrine in real systems and real constraints. Use it as a reference when you are making decisions, designing workflows, or repairing things that broke under pressure.

The backdrop: former Warsaw Pact, new realities

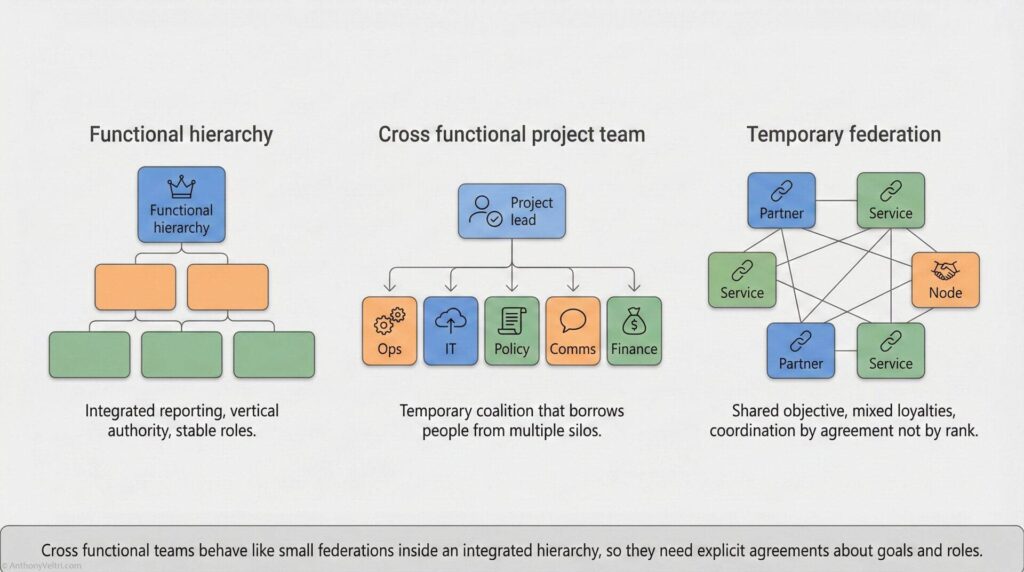

The Fire Network: The dispatch system isn’t a top-down hierarchy (Left). It is a Federated Network (Right) where Local, Geographic, and National nodes coordinate through shared agreements, not just command. The Federated Reality: The workshop wasn’t a Hierarchy; it was a “Temporary Federation.” Success depended on shared agreements between sovereign nations, not top-down command.

In 2010, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers ran a Civil-Military Emergency Preparedness (CMEP) programme that brought together former Warsaw Pact nations to practice how they would respond to large-scale emergencies.

They had a problem that will sound familiar to anyone in modern alliances:

- Everyone had their own systems, data and doctrine.

- Disasters and crises do not respect those boundaries.

- They needed practical ways to see a shared picture and make decisions together.

USACE approached DHS because they wanted to offer guidance on how a geospatial C2 / C4ISR viewer like iCAV could support that kind of civil-military work. My director, Michael Clements, was asked to provide a DHS lead.

He asked me, as branch chief, to do it.

The engagement was set up as a multi-country event, with about one hundred participants from across the region. We would run one event in Chișinău, Moldova, then another in Kyiv, Ukraine.

On paper, it was a standard international workshop with six months of planning behind it.

In practice, the plan met the Iceland ash cloud.

When the map stops matching the terrain

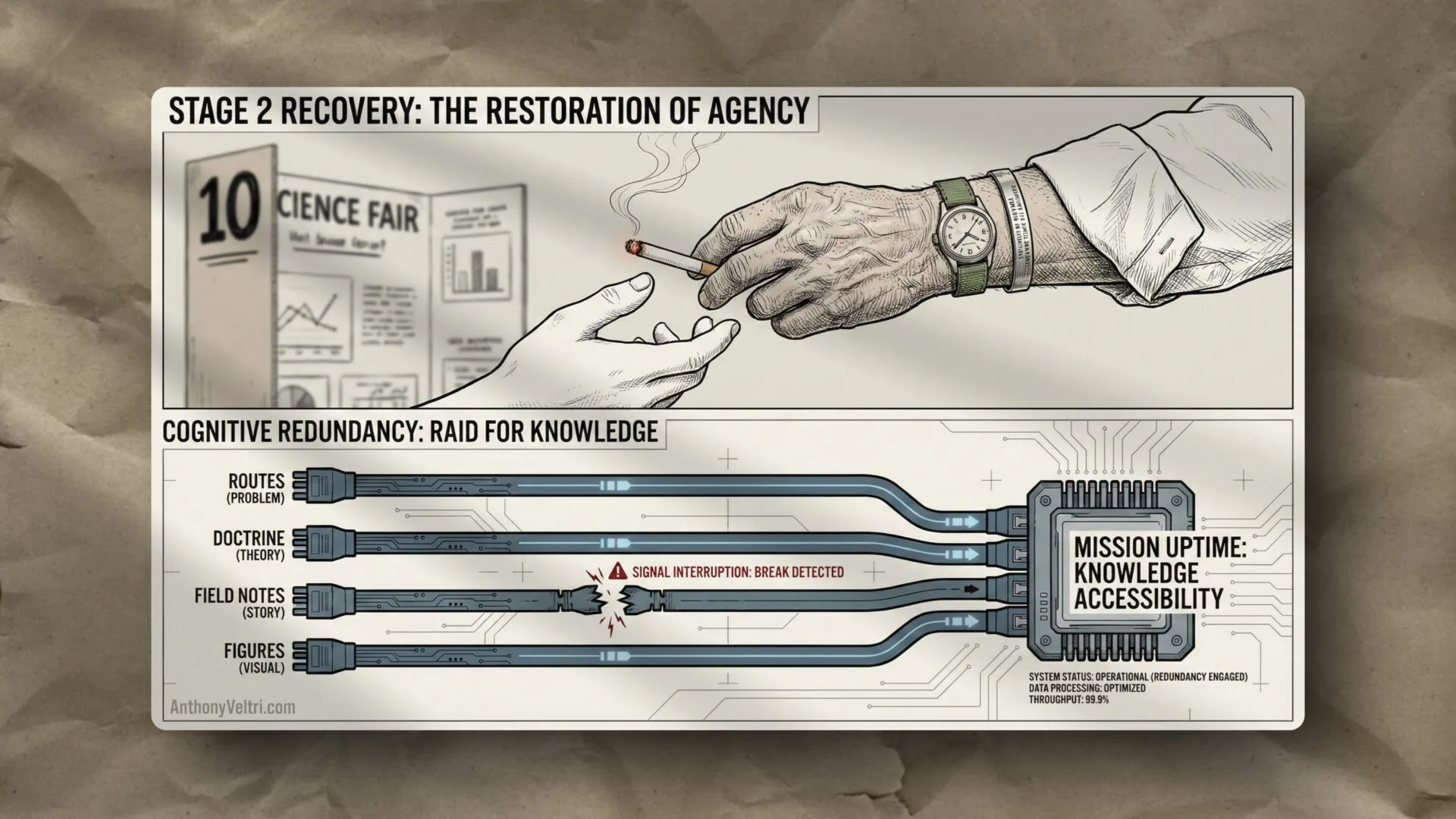

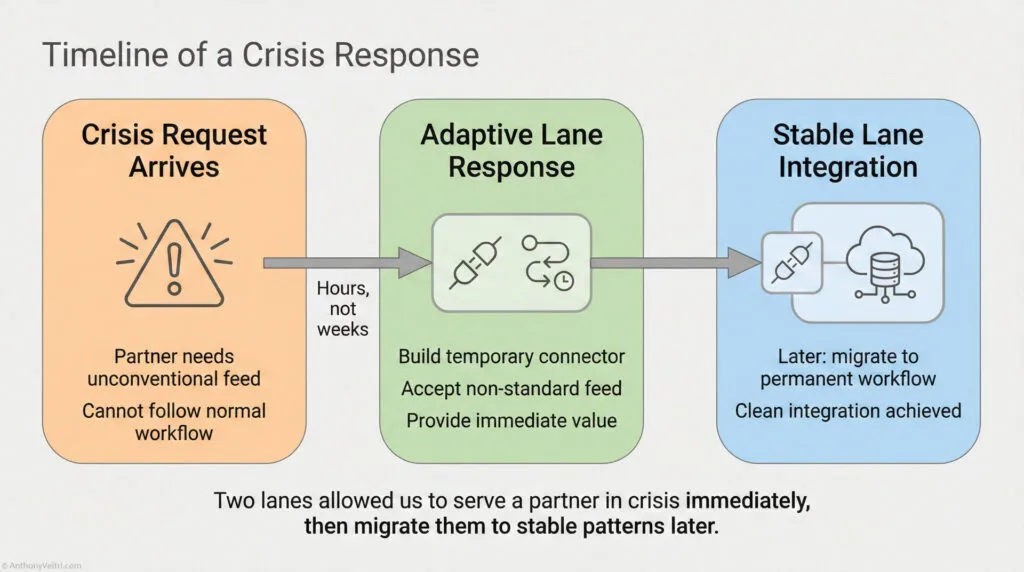

Crisis Request –> Adaptive Response (Hours) –> Stable Integration (Later). What is the minimum viable picture? Intent Fills the Gap: When the stable data feed fails, intent allows the team to shift instantly to an adaptive response (manual coordination, radio, local maps) without freezing.

We finished the Moldova portion and I boarded the flight from Chișinău to Kyiv.

Somewhere over Europe, the ash cloud disruption caught up with us. Instead of landing in Ukraine, the flight was diverted to Vienna.

I stepped off the plane into a situation that will feel familiar to anyone who has travelled during a disruption:

- No clear information.

- No formal customs checkpoint.

- Crowds of people sprinting for taxis and hotel rooms.

- Long lines, short tempers, bad weather.

I did not speak German at the time. It was raining, getting dark, and everyone on the diverted flight was suddenly competing for the same limited beds and transport.

I went from hotel to hotel. Six “no vacancy” answers in a row. The seventh, a hotel just off the Ringstraße facing the Austrian Parliament, finally had a room.

It was well over my allowed per diem. I booked it anyway.

My logic was simple: I was cold, wet, jet-lagged, and responsible for a mission that had not gone away just because the flights were cancelled. I would justify the overage later. First I needed food, sleep, and a stable base to work from.

From Vienna, I explored options to salvage the trip:

- Could I take a train from Vienna to Kyiv?

- Could I route through other countries?

- What were the restrictions?

One route would have required passing through Transnistria, which was off-limits at the time. That path was closed.

Eventually, with a mix of rebooked flights and a little luck, I made it to Kyiv.

For several days, I was the only member of the U.S. delegation who did.

“Of all the people we have, I’m glad you’re the one who’s there”

I kept my director, Michael, updated throughout.

At one point he said something that has stuck with me ever since:

“Anthony, this is going to sound awful, but of all the people we have, I’m glad you’re the one who’s there.”

On the surface, it sounds like he is happy I am the one suffering.

What he actually meant was:

- “You are the one I trust to figure this out.”

- “You can operate without a script, without the rest of the team, and without perfect conditions.”

- “You will get there, you will represent us well, and you will deliver what people came for.”

He was right about the conditions.

Because I was the only U.S. official on scene for the first several days:

- I was the sole trainer delivering the geospatial C2 / iCAV content to about one hundred participants.

- The senior U.S. presence that would normally attend formal events was delayed by the same ash cloud issues, which meant I ended up as the ranking American in the room more than once.

- I had to give toasts, take meetings, and operate at a level above my formal pay grade.

On paper, I was a branch chief and technical lead.

In practice, for that window of time, I was the face of the U.S. delegation. This wasn’t an ego trip… it was a structural vacuum. The “Lead” box was empty, so the “Member” box had to expand to fill it.

One important boundary: this is not a suicide pact

I want to be very clear about something.

This story is an example of rising to the occasion when the system breaks. It is not a promise that I will always:

- Throw myself on the grenade for someone else’s bad planning, or

- Endlessly absorb risk, stress and cost to patch over structural failures.

If a system routinely requires people to behave this way, the problem is not that you need more “heroes.” The problem is that the system is broken.

What happened in 2010 was:

- A genuine external shock (a volcanic ash cloud)

- A time-bounded, high-visibility mission

- A one-off stretch where it made sense for me to dig deep and carry more than usual

That should be the exception, not the standard operating model.

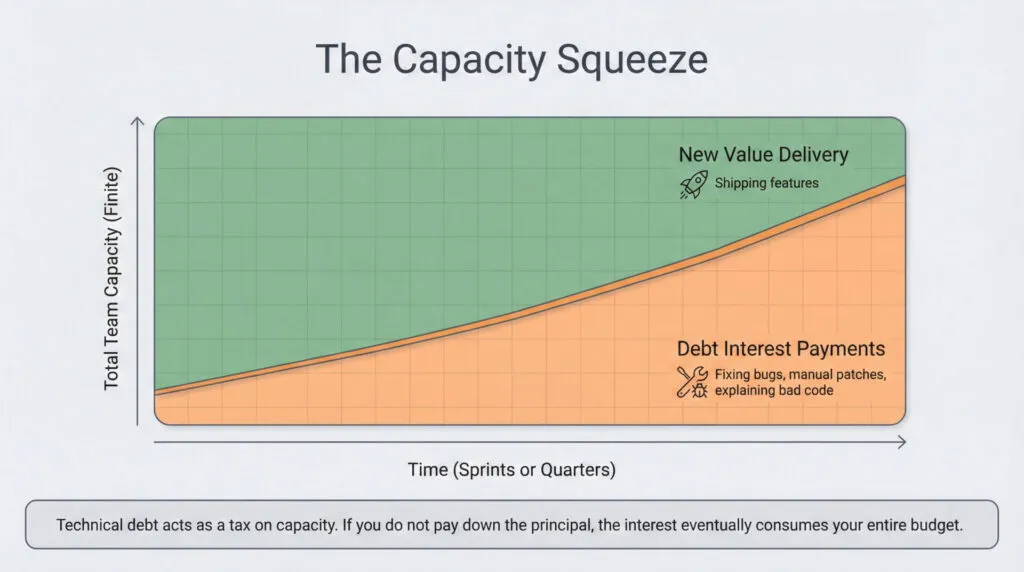

One of the reasons I care so much now about doctrine, guardrails and portfolio thinking is that I have lived what it looks like when the system quietly assumes there will always be a “responsible adult” who will just figure it out.

Sometimes I can be that adult.

I am not willing to build my life around being that by default.

What this taught me about responsibility

Looking back, there are a few reasons I keep this story close.

First, it was a live-fire exercise in the difference between authority and responsibility.

- I did not suddenly get more formal authority.

- I did suddenly carry more practical responsibility, because I was the only one who had made it to the room where the work was happening.

Second, it reinforced a pattern I have seen again and again:

In federated, high-consequence environments, the person who can stay calm, improvise within constraints, and keep the mission moving becomes the de facto leader, whether their badge says so or not.

Nobody at that event cared about my exact title. They cared that someone showed up, understood the material, respected their context, and could navigate both the technical and diplomatic sides of the work.

Third, it was a reminder that systems fail in very human ways.

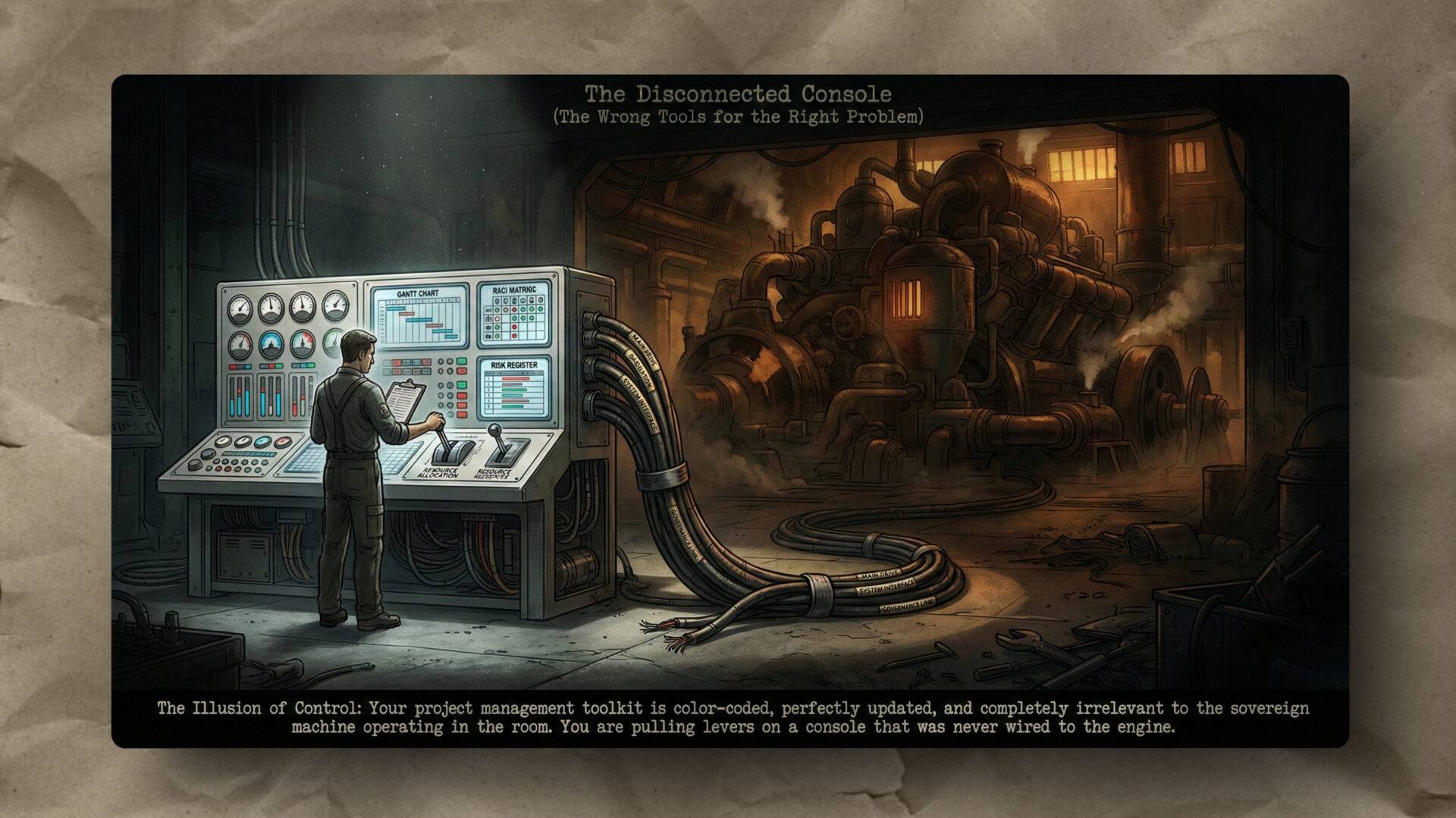

All the planning, schedules and Gantt charts did not survive first contact with a volcanic ash cloud. What mattered was:

- A passport

- Enough good judgment to bend rules without breaking them

- The ability to make decisions alone with incomplete information

The system could not guarantee the mission. Someone on the ground had to.

Why this matters to the work I do now

The reason I tell this story is not nostalgia.

It is because much of my current work lives in the same pattern:

- High-consequence environments

- Federated realities

- Limited slack for nonsense

Whether it is NATO, a federal agency, or an owner-operator with a small team, the questions rhyme:

- When flights are cancelled, who still gets there?

- When leadership is missing, who can still host the dinner and give the toast?

- When the plan breaks, who can still move the work forward in a way others can trust?

The labels change. The pattern does not.

If you are responsible for systems and missions like that, you do not just need someone who can write a nice strategy slide.

You need someone your equivalent of Michael can point to and say:

“Of all the people we have, I’m glad you’re the one who’s there.”

Last Updated on December 9, 2025