Field Notes: What I Learned Writing The Government Video Guide

Before AI, before everyone had a 4K camera in their pocket, video inside government felt risky and mysterious.

Executives worried about looking foolish.

Scientists worried about oversimplifying their work.

Comms teams worried about policy, branding, and accessibility.

And everybody avoided the camera.

That was the environment at the U.S. Forest Service in 2017 when I decided to write something I called the Government Video Guide – a practical handbook for people inside agencies who knew they needed video, but did not want to become “video people.”

This is the story behind that guide, what I learned from using it in the field, and how the same patterns still apply in a very different media landscape today.

From scattered tribal knowledge to systematic doctrine

The Government Video Guide wasn’t compiled from existing documentation. It was extracted from practitioners across agencies who had figured out what worked through trial and error but had never written it down.

I interviewed video producers, public affairs specialists, executives who had been filmed, and staff who had survived awkward shoots. The methodology was the same inverted anti-elicitation approach I’d been refining: structured questions that revealed operational patterns rather than just collecting opinions.

“What made that shoot feel safe?” “When did someone freeze up and why?” “What pre-shoot conversation changed how the footage turned out?” The answers exposed the real friction points that no equipment manual could address.

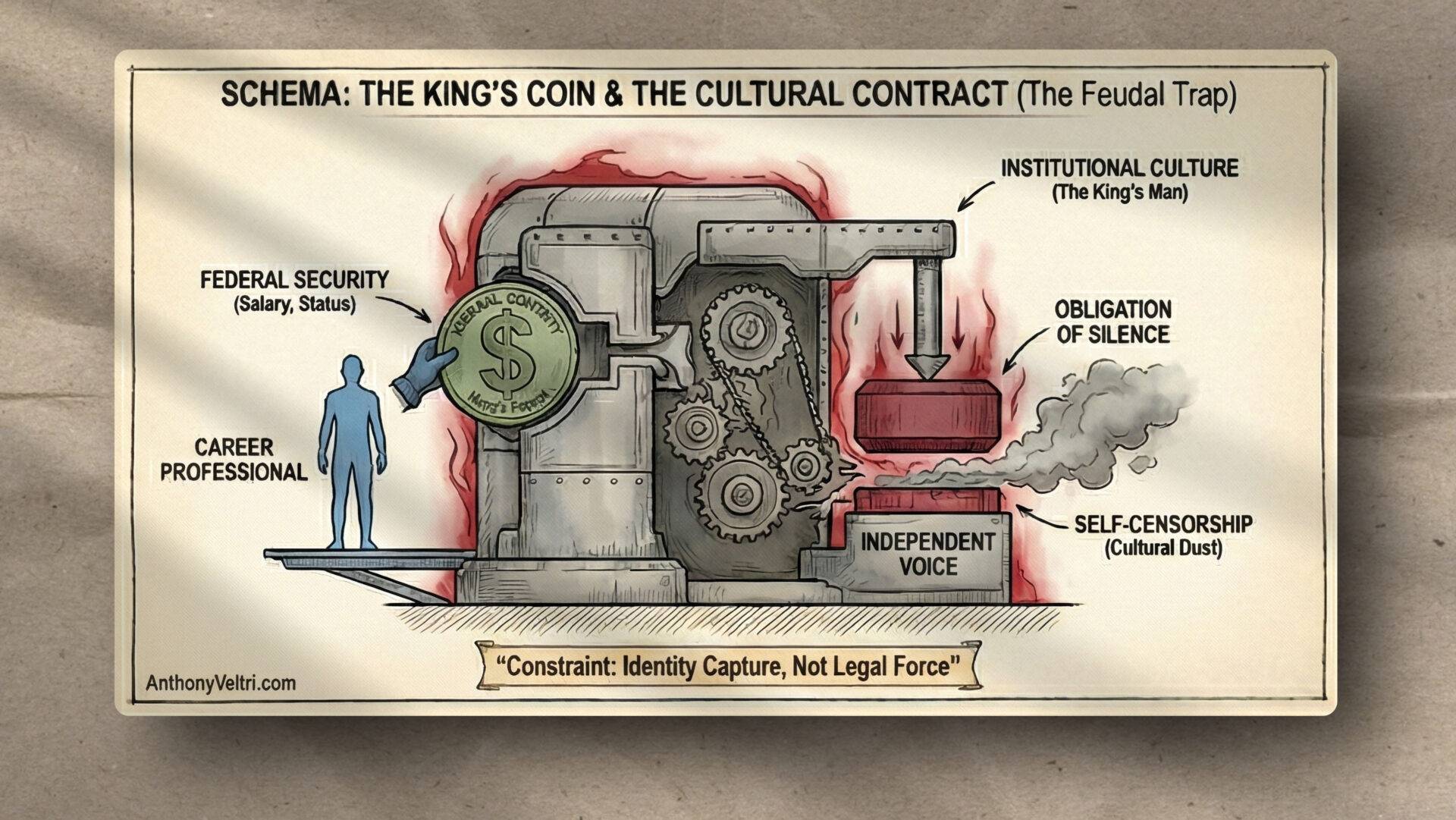

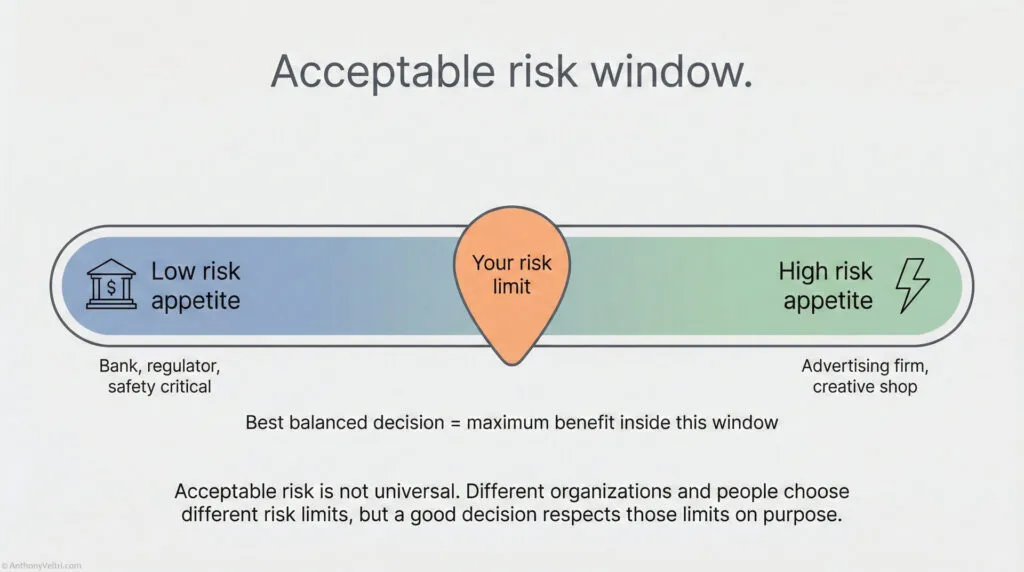

Government video sits in a strange risk zone. The consequences of getting it wrong are high (legal exposure, political blowback, damaged credibility), but the process is often treated as low-risk creative work. That gap between perceived and actual risk was causing the friction.

I structured the guide around that insight. It wasn’t a technical manual about cameras and lighting. It was a risk management framework disguised as video guidance. How to create psychological safety before the shoot. How to frame questions that get authentic responses. How to navigate the political minefield of who appears on camera and what they’re allowed to say.

The guide reduced the knowledge barrier for people who needed video capability but didn’t want to become video people. More importantly, the structured knowledge extraction methodology I used to build it proved more valuable than the guide itself. That same approach later informed how I documented operational knowledge across wildland fire, disaster response, and enterprise architecture.

Why I Wrote It

The same problems kept repeating:

- Leaders knew they should be using video to reach stakeholders, but did not know where to start.

- Subject matter experts were willing to help, but were camera shy and overloaded.

- Every new project was treated as a one off. Gear choices, scripts, formats, captions, accessibility – all reinvented from scratch.

At some point I realized I could keep answering the same questions in hallway conversations, or I could build a reference that let people make progress without me in the room.

The Government Video Guide was my answer to that.

It was written for:

- Government executives and managers

- Scientists and technical experts

- Program staff who needed to communicate impact, not just compliance

The goal was simple:

Give normal people inside government a clear, accessible playbook so they can plan and deliver useful video without needing a film crew.

What The Guide Actually Did

The book was not about turning people into filmmakers. It was about lowering friction and fear so they could use video as a tool in service of mission.

At a high level, it covered four things.

1. Purpose and audience

- Who you are talking to

- What decision or behavior you are trying to support

- How video fits alongside your other communication channels

2. Gear and technical basics

- How to choose “good enough” cameras, audio, and lighting

- Simple setups that work in real offices and field locations

- Section 508 and captioning considerations baked in from the start

3. Scripting and structure

- Simple formats for short explainers, training pieces, and updates

- How to get subject matter experts talking like humans instead of reading bullet points

- Ways to respect scientific nuance without losing the audience

4. Workflows and roles

- Who does what before, during, and after a shoot

- How to avoid the “all on one overfunctioning person” pattern

- How to build repeatable processes instead of one heroic effort

The thread through all of it was this:

Video is a tool in service of mission, not a vanity project.

The Video Testimonial Guide – Making Program Stories Repeatable

Later, I saw a related gap.

We had programs that were quietly transforming people’s work lives and wellbeing. Participants were having real, measurable changes. Yet when it came time to tell the story, teams froze.

They did not know what to ask on camera.

They worried about saying the wrong thing.

They defaulted to generic “it was great” soundbites that convinced no one.

So I created a one-page Video Testimonial Guide that broke the problem into three parts.

1. Craft and technical

- Steady shot, simple background, clear audio

- Test a 30 second recording and play it back before you start

- Use whatever camera you have, but stabilize it and get the mic close

Objective: A clean, watchable clip that does not distract from the speaker.

2. Confidence and connection

- Do not “talk to the lens” – imagine you are speaking to one specific person just behind the camera.

- That person is:

- Unconditionally supportive of you

- Someone who would benefit from the program

- Someone who does not know the details and needs your help

Objective: Help the speaker feel like they are talking with a real human, not trying to pass a test.

3. Content and questions

Instead of handing people a script, the guide offered prompts, such as:

- What pushed you to try this program

- What doubts or concerns you had going in

- What changed in your work life

- What changed in your personal life or wellbeing

- What you would tell a colleague who is on the fence

- What you think we should improve next time

Objective: Capture specific, grounded stories that make it easy for others to see themselves in the experience, and capture real feedback about what to fix.

Hurricane Florence – Using The Guide In Real Disaster Recovery

The first serious field test of this approach came during Hurricane Florence recovery, working with the USDA Food and Nutrition Service.

I was embedded in shelters and with local partners. The goal was not to “get shiny testimonials.” It was to understand what was actually happening on the ground:

- End users who simply needed food and stability

- Shelter managers and staff trying to keep people safe and fed in chaotic conditions

- Federal staff who needed honest feedback so they could improve for the next event

I used the testimonial guide as a structured conversation tool:

- Same core prompts.

- Same emphasis on plain language, not agency jargon.

- Same commitment to ask “what should we do better next time” and actually listen.

One of the FNS managers I supported told me something along the lines of:

I do not know how you got these people to say what they said, but their words were more powerful than our own talking points.

The answer was simple. I was not trying to make anyone repeat a script. I was guiding them through questions that helped them notice:

- What had changed for them

- What had not worked

- What they would want someone else to know

That is what a good “testimonial” is in this context.

Not a commercial. A structured way to let people tell the truth in a form that others can use.

Those conversations did two jobs at once:

- They gave leadership vivid, human stories about how policy landed in real lives.

- They gave the program concrete suggestions for how to respond better in the next crisis.

What This Experience Taught Me

Writing and using these guides forced me to codify patterns that I still use today, even in AI heavy environments.

1. Tools change. Human friction does not.

People are still camera shy.

Leaders still worry about speaking plainly.

Programs still struggle to show impact.

Whether you are shooting on a phone or auto clipping with AI, the human side is the hard part.

2. The right playbook makes normal people powerful.

A good guide gives non specialists enough structure to move forward safely. It respects their time and intelligence. It lets them operate at a higher level without adding twenty new tasks to their plate.

3. Accessibility and inclusion are not optional add ons.

Because this work lived in government, Section 508 and similar requirements were part of the design, not an afterthought. That mindset translates directly to any organization that takes equity and access seriously.

4. You cannot be the hero and the system at the same time.

These guides worked because they let other people carry the work forward.

When one person becomes the bottleneck for every video, they burn out and the mission suffers. Systems beat heroics.

How I Use This Now – And Where The Boundaries Are

I am proud of the Government Video Guide and the Testimonial Guide. They helped real people do real work more effectively, in environments that were often messy, emotional, and high stakes.

At the same time, I have learned something about my own pattern: if I am not careful, I will quietly take on too much and build entire systems for other people, without clear agreements or limits.

So today, this experience shows up in my work in a different way:

- I design lightweight frameworks and guides that teams can actually use, instead of giant manuals that no one reads.

- I build for leverage and handoff, so the system does not depend on me personally to keep running.

- I am explicit about scope and boundaries. This kind of work now lives inside a defined engagement, with clear outcomes, not as an open ended favor.

If you lead a program or team that is doing meaningful work but struggling to show it – especially through video, story, and feedback loops – this is the kind of problem I like solving:

- Clarifying your audience and purpose

- Giving your experts safe, simple ways to show up on camera

- Creating repeatable templates for testimonials and after action insight

- Making sure accessibility and policy requirements are built in from the start

The tools will keep changing. The fundamentals of human connection, clear story, and respectful structure will not.

This is one of the places I have been building those fundamentals for a long time.

Last Updated on December 23, 2025