Field Notes: What The Mobile Mapping Unit Taught Me About Forward-Deployed Systems

I sometimes forget that one of the most important things I ever built was a Mobile GIS lab and operations center in a 26-foot box truck I bought on eBay.

At the time, it just felt like the next logical step in a long chain of decisions. Looking back, it is the through line that connects remote sensing, wildland fire, Hurricane Katrina, RF engineering, WiMAX and VoIP backhaul, and a lot of how I think about forward-deployed systems today.

This is the story of that truck, what we actually did with it on the Gulf Coast, and why it still matters for how I design and deploy technology. It is also a story about being invited into a team that did not have to trust me, and what that kind of trust feels like from the inside.

In a crisis, sovereignty belongs to the person (entity) who can print the map.

During Hurricane Katrina, the federal “Common Operating Picture” was a hallucination of roads that no longer existed. This briefing details the deployment of the Mobile Mapping Unit (MMU) (a disconnected intelligence module that became the only source of truth for miles.) A lesson on why we must build for the “All Risk” reality, not the clean-room fantasy.

From Satellites To Firelines: Realizing I Was Missing The Ground

My formal work started in remote sensing and GIS.

I was in a Natural Resources department, working on wildland fire with satellite imagery. Landsat, early LiDAR, all the fun toys. My major professor kept pushing the research deeper, which is how I walked out with two master’s degrees instead of one.

The turning point was simple:

I realized I was modeling fire behavior from orbit without really knowing what it felt like on the ground.

So I started fixing that.

I sent myself to wildland fire academies, not as a novelty trip, but as part of the research:

- Brookhaven, New York Wildland Fire and Incident Management Academy

- Colorado Incident Management Academy

- A Utah academy

- Back to Brookhaven multiple times

There I learned:

- Fire behavior and ICS from the wildland side

- Fire and Aviation Management

- How incidents are actually run under pressure

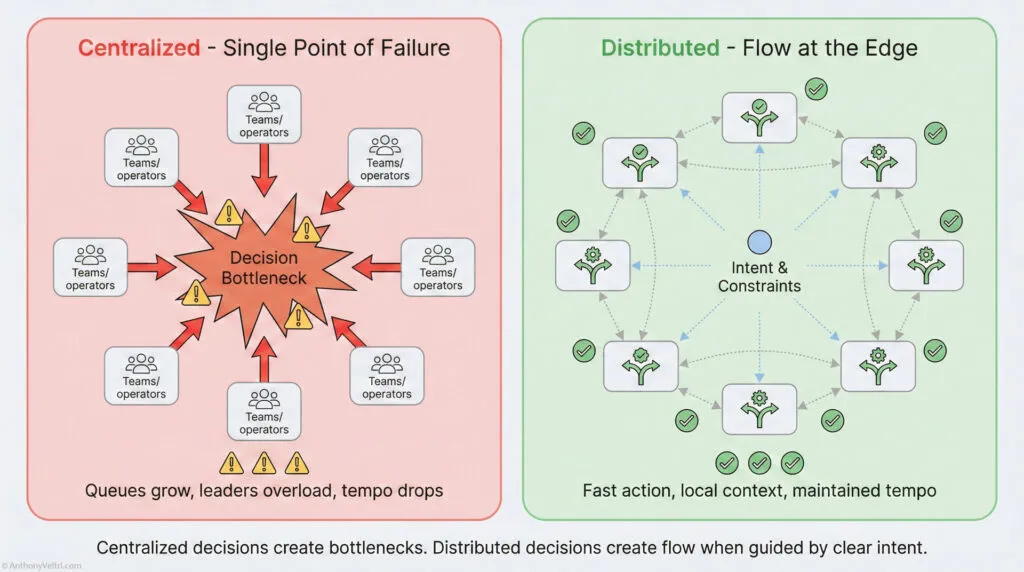

- How fragile the information picture can be when decisions are time-critical

Somewhere between those academies and the lab, a pattern clicked:

If you could bring a self contained GIS and mapping unit to the incident, you could close a real gap.

So I built one.

Buying A 26 Foot Box Truck On eBay

In my final months of grad school, I saved up and bought a 26 foot box truck on eBay.

It had been a New York State mobile testing center. High walls, insulated, an egress door with a push bar to satisfy safety rules from the 1990s. It already felt like a rolling lab.

Crucially, it came with:

- An Onan generator that could run the whole rig

- Enough interior space for desks, equipment, and people

- A layout that was easy to reconfigure

I turned it into a mobile GIS lab:

- Added a large format plotter for incident maps

- Installed GIS workstations

- Used the existing AC to keep people and hardware alive in summer heat

The Finished Product: Rapid Fire Industries Mobile Mapping Unit

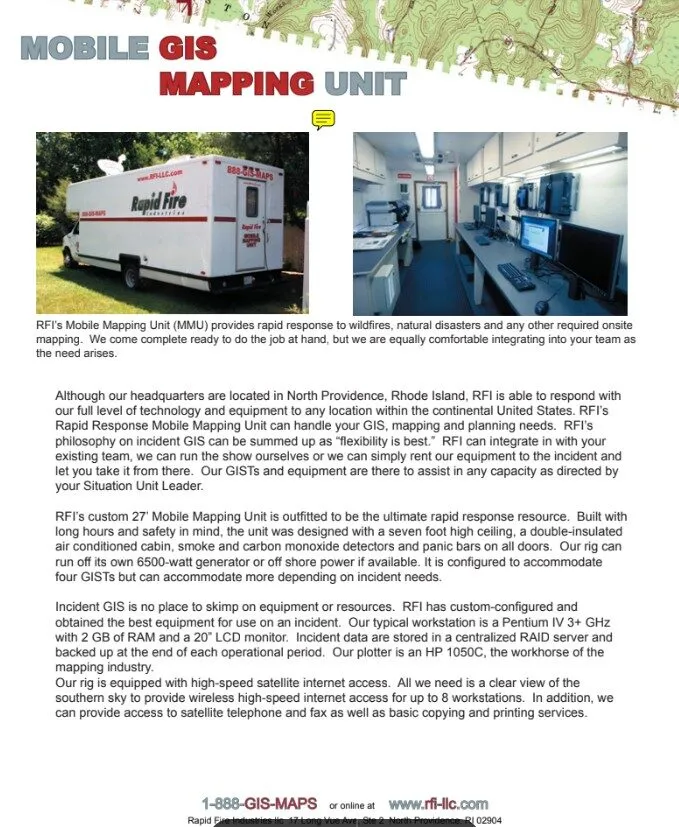

By the time I was done, the truck had evolved from a New York State testing center into a self-contained forward-deployed GIS capability. I started marketing it as Rapid Fire Industries, complete with a 1-888-GIS-MAPS phone number and a professional service offering.

Looking back at the brochure now, I see what I got right and what I have learned since.

What I got right:

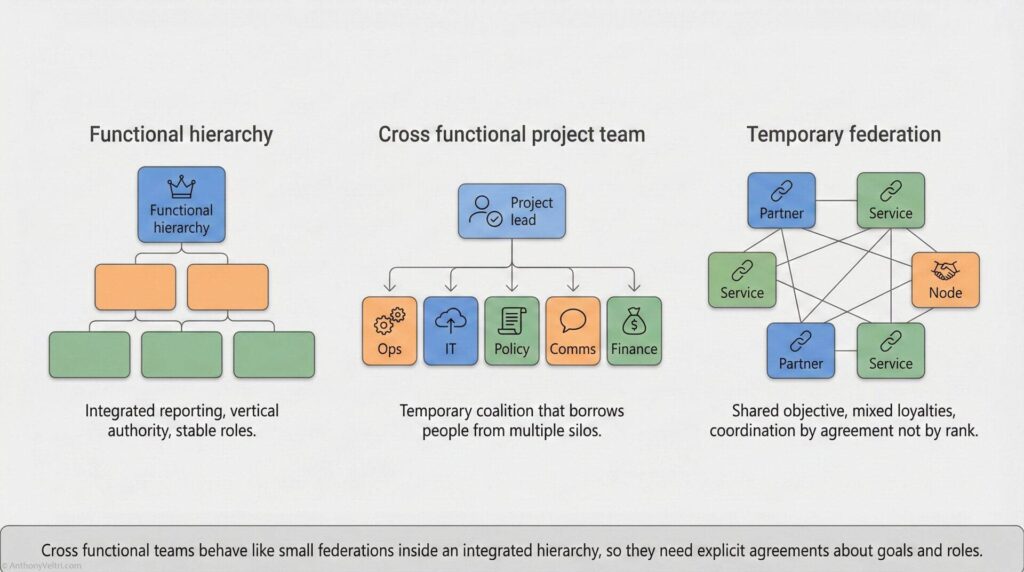

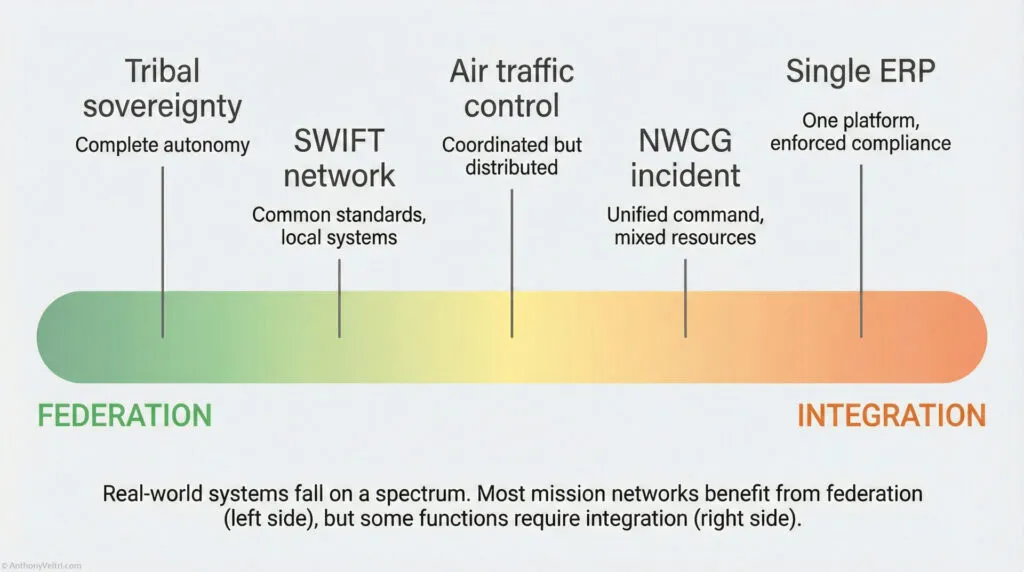

- “Flexibility is best” – that is federation doctrine, even though I did not have that language yet

- Self-contained systems that bring capability to the field instead of forcing teams to come to headquarters

- Equipment that could actually survive field conditions (7-foot ceilings, air conditioning, generator, RAID backup)

What I was still learning:

- I sold equipment specs (Pentium IV processors, 2GB RAM, HP 1050C plotter) instead of mission capability

- I listed features instead of explaining the decision support gap this filled

- I had not yet connected this to broader patterns about forward-deployed systems, stewardship, and federation

The doctrine was always there. I just did not have the vocabulary for it yet.

Here is the actual marketing brochure from spring 2005:

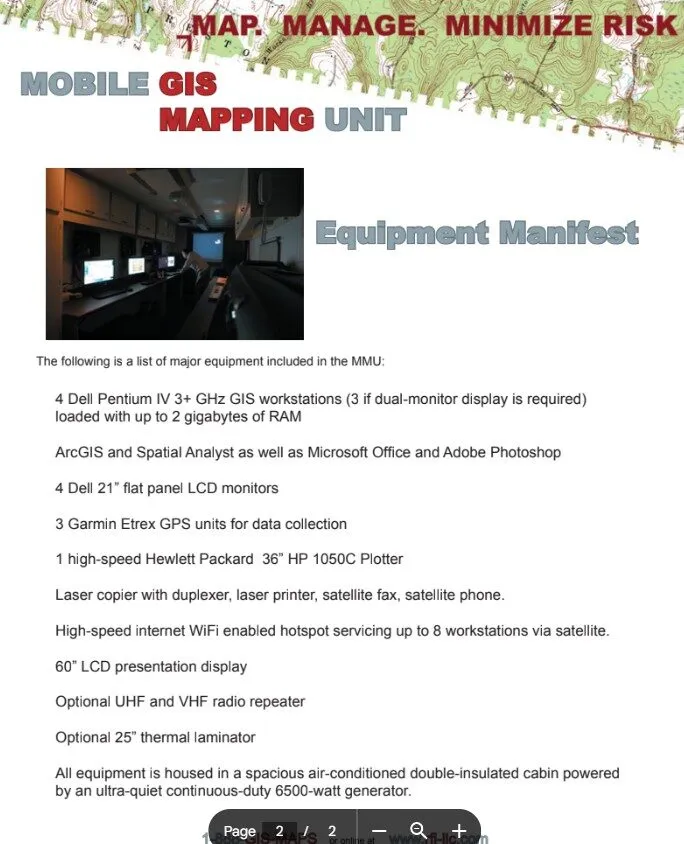

The equipment list is almost quaint now. Pentium IV processors. 2GB of RAM. Satellite internet “servicing up to 8 workstations” as if that were impressive. A 60-inch LCD presentation display that probably weighed 80 pounds.

But strip away the dated specs and you see the pattern that still matters:

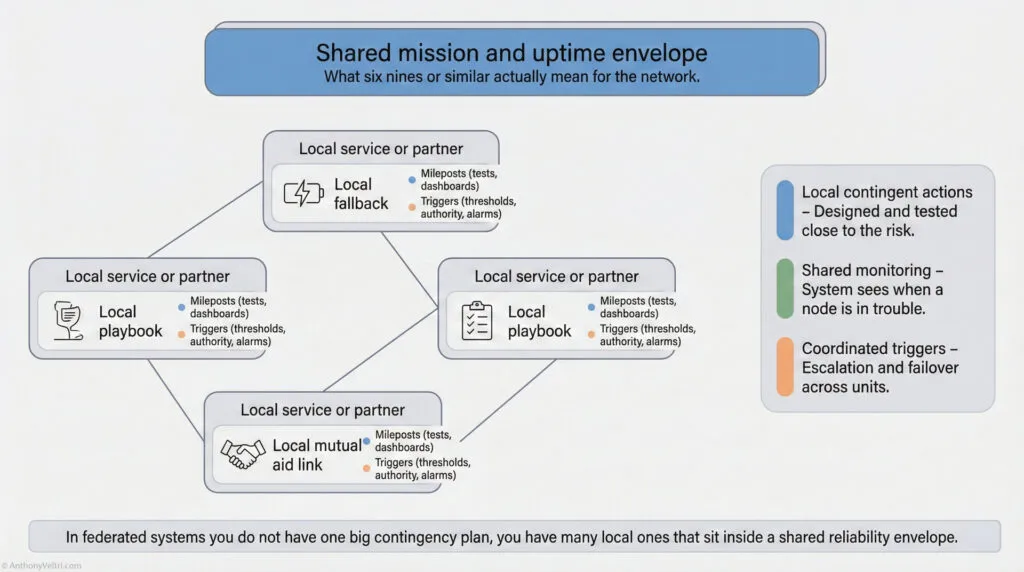

- Power independence (6500-watt generator, could run for days)

- Communications independence (satellite internet when everyone else was relying on flaky local networks)

- Data resilience (RAID server, nightly backups, the operational picture survived even if one drive failed)

- Comfortable workspace (7-foot ceilings, air conditioning, because exhausted analysts make bad maps)

- Flexible integration (“We can integrate with your existing team, run the show ourselves, or rent equipment”)

This was federation and forward-deployed decision support, 15 years before I had clear language for either concept.

The fire season that followed was not spectacular. The big wildland incidents I was mentally targeting did not materialize the way I expected.

Then Hurricane Katrina hit.

Hurricane Katrina: Deploying With Rhode Island Urban Search And Rescue

When Katrina made landfall and the response spun up, the mobile mapping unit suddenly had a very different role to play.

I deployed alongside the Rhode Island Urban Search and Rescue Task Force, and we based out of the Emergency Operations Center at Stennis, near the Stennis Space Center on the Gulf Coast.

The important part here is that they did not have to bring me in. I was not one of their long time firefighters or medics. I was the guy with the truck and the maps. They chose to fold me into their rhythm and treat that capability as part of the team.

Inside that context, the truck became:

- A mapping and geoprocessing hub for a team that otherwise would not have had that capability

- A physical anchor for electronics, radios, and computers in a chaotic, high stress environment

I later wrote a book documenting the Rhode Island USAR story and the wider response efforts we intersected with. The truck sits quietly in that story, but it was part of a much larger organism that already knew how to work together under pressure.

Katrina did more than validate the idea of a mobile GIS lab. It shoved me into a new rabbit hole: communications.

Being Welcomed Onto The Team

One of the moments that still sticks with me did not involve maps or RF. It was a flat tire.

On the way home, I caravanned with the Rhode Island team. At one point my vehicle blew a tire. A fire captain was riding with me when it happened. The whole convoy could have kept going and met me later. Instead, they all pulled over.

The tire had shredded enough to grab the mud flap, so it was not just a simple swap. The guys rolled up with the rescue rig, pulled out a battery powered Sawzall they normally used for extrication, and went to work.

It felt like a NASCAR pit crew: cut the mangled mud flap free, get the vehicle safely jacked, swap the tire, check everything, back on the road. At night. On the way home from a long deployment.

There is no way I could have done that as fast or as safely on my own.

That moment matters to me because it captures the real shape of the work:

- I brought a truck, some equipment, and skills they did not have in house.

- They brought a level of trust, teamwork, and practical capability I could not have summoned on my own.

Any story I tell about Katrina and the mobile mapping unit has to include that mutual dependence, or it is not honest.

What The Katrina Book Really Was

I did not go to the Gulf Coast planning to write a book. I went to help.

Like a lot of technical people, when I see a pain point, I start sketching the system that would fix it, often before anyone explicitly asks. The book came from noticing a different kind of gap.

States have mutual aid agreements and memoranda of understanding that let them send teams across borders when disasters hit. That does not erase the reality that those people are also needed at home.

For Rhode Island, sending a USAR task force all the way to the Gulf Coast raised real questions back home:

- Who is covering the risk here while you are gone

- What exactly are you doing down there

- Is this really the best use of our best people

The team received a welcome from the governor when they returned, and they deserved it. At the same time, there was scrutiny and second guessing around staffing and priorities that did not match what I had seen on the ground.

I was already documenting the deployment. At some point it became clear that a book could do three things at once:

- Give the team something tangible to commemorate what they had done

- Show skeptical audiences, in text and images, what the work actually looked like day to day

- Provide a narrative they could hand to anyone who asked, “Was this really worth it”

So that is what the Katrina book really was:

- Not a vanity project for me

- A piece of narrative infrastructure for them

It was a way for Rhode Island USAR to point to a single object and say, “This is where we were. This is what we did. This is why it mattered,” without having to re argue it every time.

Looking back, it sits in the same pattern as the truck and the RF lab. See the pain point, build the missing system. Sometimes that system is a box truck. Sometimes it is a book that lets people defend their own story.

Emergency Support Function (ESF) Communications: Where GIS Meets RF

On paper, my world was maps and imagery.

On the ground, it quickly turned into ESF communications, because communications and GIS are joined at the hip when you care about:

- Path loss

- Line of sight

- Where you can and cannot put antennas

I was already a licensed amateur “ham” radio operator, comfortable with RF in the high frequency world. Katrina forced me to stretch into:

- Wireless networking in a Cisco and CCNA sense (latency and packet loss wreak havoc on voice comms)

- Orthogonal frequency division multiplexing, spread spectrum, and modern radio systems

- Practical RF link budget questions like “what actually happens to signal strength when we push this link across a tree line or a low ridge”

The critical insight was that GIS is not just about pretty maps. It is a modeling tool for the RF environment:

- Use bald earth or terrain data

- Model line of sight and obstacles

- Calculate expected path loss for given frequencies, antennas, and power levels

I set up an RF lab and used GIS as the engine behind terrain-informed path loss models. That made wireless planning a lot less abstract and a lot more specific.

None of that was done alone. It plugged into a wider ESF communications effort where radio techs, IT staff, and field operators were all trying to solve the same problem from different angles.

It also opened up some strange and interesting work I never would have predicted when I was just thinking about fire and Landsat.

Climbing Towers And Modeling Path Loss

Because the RF work kept expanding, I went and got my OSHA tower climbing certification in Georgia.

I already had a background in climbing, so the height and harness piece did not scare me. The certification added:

- Safe procedures for working at height

- A better understanding of how real telecom crews operate

- A comfort level with being the person who can go up the mast, not just model it on a screen

Meanwhile, the RF lab matured:

- We treated path loss equations as living tools, not just homework problems

- We combined GIS terrain data with frequency and antenna patterns to predict where coverage would succeed or fail

- We validated those predictions in the field, often alongside people who had been doing practical RF work longer than I had

That combination of theory, modeling, and on the ground validation became addictive. It also almost pulled me fully into industry. At one point I was close to being hired by Harris Corporation to work on RF systems.

Even though that specific move did not happen, the body of knowledge stayed. It is one of the threads that still shapes how I think about any system that has to live in the real world, not just on a slide.

Distributed Antenna Systems And CW Drive Testing

In the post-Katrina period, another opportunity spun out of this work.

I met someone on the Gulf Coast who had previously run a large cell phone company in the late 1990s. His personal and business story had ups and downs, but he was fundamentally a good person who shared his experience generously and opened doors into the RF world I never would have walked through on my own.

Through that connection, I worked on distributed antenna systems (DAS) in high-end neighborhoods that did not want visible towers.

The pattern looked like this:

- Wealthy areas did not want a big steel lattice visible on the horizon

- Providers experimented with smaller antennas mounted on utility poles

- That meant you were limited in height, which meant your line of sight and path loss calculations had to be precise

To support this, we did continuous wave (CW) drive testing.

We used:

- The pneumatic mast from the mobile mapping unit

- Sometimes on the truck

- Sometimes mounted on my Honda Element

- A Berkeley Varianics Gator transmitter and receiver pair

- GPS logging for each measurement point

We would:

- Transmit a known signal from a given height and location

- Drive test the area

- Log RSSI at many points

- Match those readings against the GIS modeled expectations for path loss

That closed the loop between:

- RF theory

- GIS modeling

- Actual received signal strength in the streets where people lived

Even if DAS has morphed and the brand names have changed, the pattern is very current: small cells, careful RF planning, and the need to understand how the environment shapes signal in practice.

WiMAX, Backhaul, And Phone Calls That Should Not Have Been Possible

Tower climbing and RF work pulled me into one more ecosystem that has aged out in name but not in concept: WiMAX.

Through some of the same contacts, I got involved with early WiMAX deployments that needed infrastructure installed before the Canopy-style systems most people remember. The technology names have moved on. The lessons have not.

On the Mississippi side, the work had two sides:

- Customer premise equipment

- Getting last-mile access points into the right places

- Backhaul

- Making sure those edge links had enough capacity upstream to matter

Backhaul is where things got especially interesting. We were not just lighting up bandwidth for its own sake. We were pulling in capacity for telephony over IP.

That meant stepping into:

- VoIP as more than a buzzword

- SIP trunking and call routing

- The practical reality that voice quality and reliability ride on top of RF and IP decisions

I do not consider myself a telephony expert. I do consider this period a critical part of my education.

Because here is the real point:

Seeing a phone ring in a shelter that should not have had working telephony, and knowing that the call is riding on RF links and backhaul paths that a whole group of people designed and installed together, is very different from reading about VoIP in a manual.

Those calls mattered.

They connected families, case workers, shelter staff, and logistics coordinators in places that would otherwise have been radio-only or dark altogether. RF skills and backhaul design were not abstract. They were part of a chain of decisions and contributions that made those calls possible.

What The Mobile Mapping Unit Really Was

It is easy for me to treat the mobile mapping unit as “that weird grad school project,” but if I zoom out a bit, it takes a different shape.

It was:

- A forward deployed decision support system on wheels

- A platform for geospatial processing, RF modeling, and communications planning

- A way to bring tools that were normally stuck in labs or offices directly to incidents and field environments

Technically, it wrapped up:

- GIS workstations

- Plotting capability

- Power and cooling

- RF test equipment

- A Clark pneumatic mast and field-deployable antennas

Operationally, it wrapped up:

- Incident mapping for fire and USAR

- Terrain-based path loss modeling

- RF planning and validation

- Early broadband wireless and VoIP backhaul for places that otherwise would have been offline

None of that existed in a vacuum. It only worked because teams were willing to let that capability plug into their operations, teach me how they worked, and trust me enough to let the truck sit inside their perimeter.

Why This Still Matters For How I Work Now

A few lessons from that period have never really left.

1. You cannot architect only from the rear

The fire academies and Katrina deployment forced me to reconcile:

- What the models say

- What the sensors see

- What the ground actually feels like at two in the morning when comms are flaky and the weather is bad

Today, when I think about digital transformation, portfolio systems, or NATO style C2, that bias shows up as:

The design has to survive contact with reality.

Not just in theory, but under load, under stress, and in less than ideal conditions, alongside teams who already have their own ways of working.

2. Self contained units unlock capability for teams that would never get it otherwise

Rhode Island USAR did not have the budget or staffing to stand up their own GIS and RF lab.

They did have:

- A mission

- People willing to work

- A gap that could be closed by one well designed mobile unit

That pattern repeats:

- Agencies that cannot justify a full time architect, but desperately need better systems

- Teams that are buried in work, not lacking in will

- Situations where a forward deployed unit, physical or virtual, can unlock disproportionate value

This is part of why the idea of a forward-deployed engineer or forward-deployed architect resonates so strongly with me. I have spent years doing a version of that role from a truck, but never alone.

3. The through line matters more than any one credential

On paper, the Katrina work left a trail:

- A book

- Labs

- Certifications

- Even an almost offer at Harris

None of those were the point at the time. The real asset is the through line:

- Remote sensing and fire

- Field academies and ICS

- Building the mobile unit

- Katrina mapping and EOC work

- ESF communications and RF modeling

- DAS and CW drive testing

- WiMAX deployments and VoIP backhaul for shelters

These are not random episodes. They are a consistent pattern of:

See a gap.

Ground truth it.

Build a practical, forward deployed system.

Plug it into existing teams.

Validate it under real conditions.

That is the pattern I carry into newer work, whether the domain is disaster response, federal portfolios, or executive dashboards.

Where This Fits In My Doctrine

If you strip the details away, the mobile mapping unit is an early expression of several doctrines I talk about now. Plenty of other people have built their own versions of this pattern in different domains. This is simply the version I happened to live through up close:

- Forward deployed capability instead of distant, abstract support

- Useful interoperability between GIS, RF, and operations, not perfection in a single domain

- Resilient systems that can operate with degraded infrastructure

- Named stewards for critical systems, not anonymous “IT” somewhere else

- Interdependence between specialties, where trust and roles matter as much as tools

It is also a personal reminder that:

- I have a tendency to build systems that only I can maintain if I am not careful

- The healthy version of that pattern is to build systems that can be handed off and lived in by teams, not just operated by me

The mobile mapping unit came from a time when I could self-fund bold moves in a way that would be harder now. The knowledge, the doctrine, and the way of thinking it forced on me are still very much alive and reusable.

This Field Note is partly for anyone reading, and partly a memo to my future self:

Do not forget that you have already built a forward deployed decision support platform once, under pressure, inside teams that trusted you and that you trusted in return.

The point is not that my story is unique, but that this kind of lived, forward-deployed experience is exactly what I try to bring into how I design and critique systems today

That experience is not just a story from the past. It is part of the foundation you are standing on now.

Last Updated on February 11, 2026