Architect as Translator: Earplugs in the off-site Data Hall, Briefing at HQ in DC

There is a certain kind of day that captures what architecture really is.

In the morning you are in a off-site data center with earplugs in, standing between racks while you configure servers and network paths. In the afternoon you are in a conference room in Washington, describing the status and risks of that same system to executives who will never see the hardware.

Nothing about the hardware changed in those few hours. What changed was the language and the perspective.

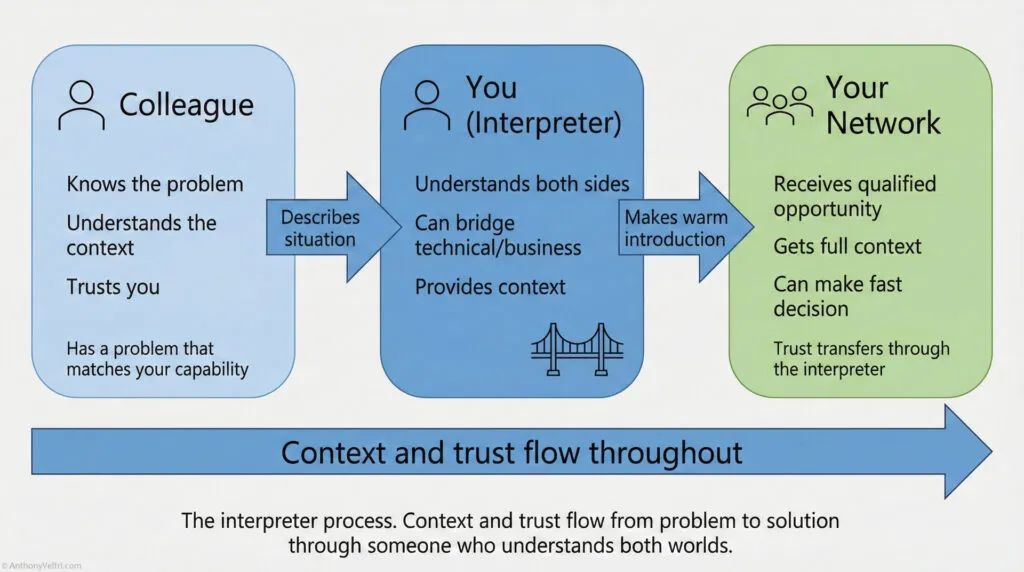

Architecture is not just about diagrams and patterns. It is about translation.

When I served as branch chief for the iCAV program, I had that split day experience often. iCAV was a geospatial viewer and data platform that supported critical infrastructure awareness and incident response. At one point we had it stood up at Mount Weather as a temporary home and needed to move it to a flagship data center at Stennis, while maintaining failover and service continuity.

Translation was the job.

With the technical staff and contractors in the data hall, the conversation was concrete.

- Which services run where.

- How we handle Akamai configuration.

- What failover actually means in terms of DNS, replication and latency.

- How we keep ingestion layers running while the underlying infrastructure moves.

With executives and senior stakeholders, the conversation was different.

- When can we schedule the cutover without exposing the program.

- What happens if Stennis goes down and we are still relying on Mount Weather.

- How to explain to external partners that the URL they use stays the same even if the path behind it changes.

- What tradeoffs we had made between speed, cost and safety.

In between those worlds, details that mattered in one conversation were noise in another.

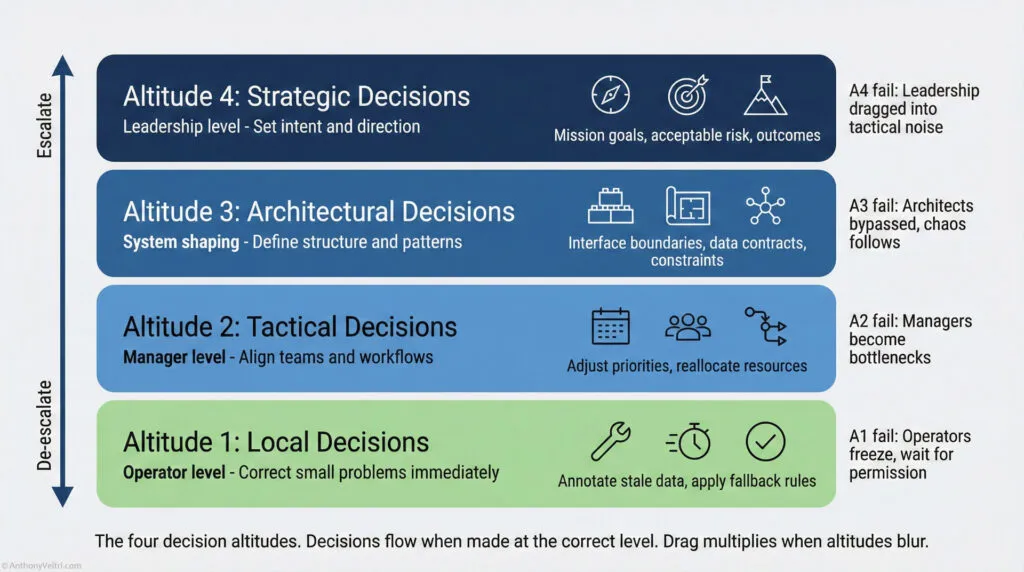

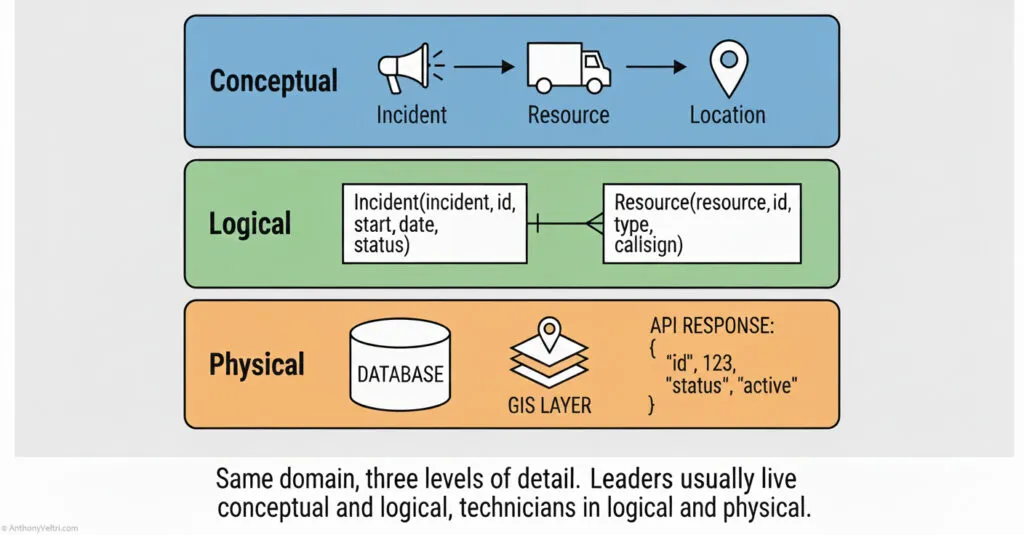

The Language Ladder: Engineers speak “Physical” (DNS, Latency). Leaders speak “Conceptual” (Availability, Risk). Your job is to translate up and down this ladder without losing truth.

If you describe DNS failover mechanics to a senior leader who only wants to know whether the system will be available during hurricane season, you are not serving them. If you describe “high availability” to an engineer without specifying RPO, RTO and the real constraints of the migration, you are not serving them either.

The architect as translator holds five responsibilities.

- Keep the mission clear. Everyone, from data center staff to executives, should be able to answer the question: what is this system for, and who gets hurt if it fails.

- Protect the truth at each layer. You simplify, but you do not lie. The executive version and the technical version must both be faithful to the same underlying reality.

- Carry risk information across boundaries. A risk seen by a technician must not die in the wiring closet. A pressure from leadership must not arrive in the form of vague demands that distort the design.

- Respect both languages. Technical language is not a problem to be solved. Executive language is not an annoyance to be tolerated. Both are valid in their own context.

- Refuse to be a one way channel. Translation is bidirectional. The architect brings constraints up as well as priorities down.

The danger, especially in large organizations, is that these layers drift apart. Engineers start believing leadership lives in a fantasy world of PowerPoint. Leaders start believing engineers are allergic to strategy and timelines. At that point, architecture becomes a diagram on a wall, not a living practice.

The translate role is not glamorous. On paper it looks like “meetings” and “presentations.” In practice it is the job that holds the system together.

- When you explain to a partner why you cannot change the number of seconds in a day to improve their uptime statistics, that is translation in defense of integrity.

- When you take a fire community’s hard won lessons and help turn them into standards that both developers and incident commanders can live with, that is translation between doctrine and implementation.

- When you walk from a noisy server room to a quiet briefing and carry the same facts in two different grammars, that is translation in motion.

My doctrine is this.

If you cannot explain your system to both the person who pays for it and the person who pagers on it at 3 a m, you do not understand it well enough to be its architect.

The opposite is also true.

If you can stand in both rooms, hear both sets of concerns and carry meaning cleanly between them without distortion, you are already doing architecture work, whether your title admits it or not.

Earplugs in the data hall. Jacket on in the briefing room. Same system. Same mission. Two languages. One responsibility.

Last Updated on December 9, 2025