Bay St. Louis: Trust Before Logos After Hurricane Katrina

In late 2005, in places like Bay St. Louis on the Mississippi coast, I learned the hard way that trust and sovereignty mattered more than any federal logo on a badge.

This page is a Doctrine Guide. It shows how to apply one principle from the Doctrine in real systems and real constraints. Use it as a reference when you are making decisions, designing workflows, or repairing things that broke under pressure.

The backdrop: a coast that had already paid

Hurricane Katrina did not hit every community the same way.

New Orleans dominated the headlines, and for good reason, but across the Gulf Coast there were smaller places like Bay St. Louis that were just as torn up and far less visible.

I deployed there on the federal side to support with geospatial and situational awareness work. The idea was simple on paper:

- Bring mapping and data.

- Help local and state officials see what was damaged.

- Support decisions about where to send people, supplies and attention.

In reality, it was my first real exposure to what it means to show up in a disaster as “federal” in a place that had its own history, politics and scars.

Logos do not sandbag streets

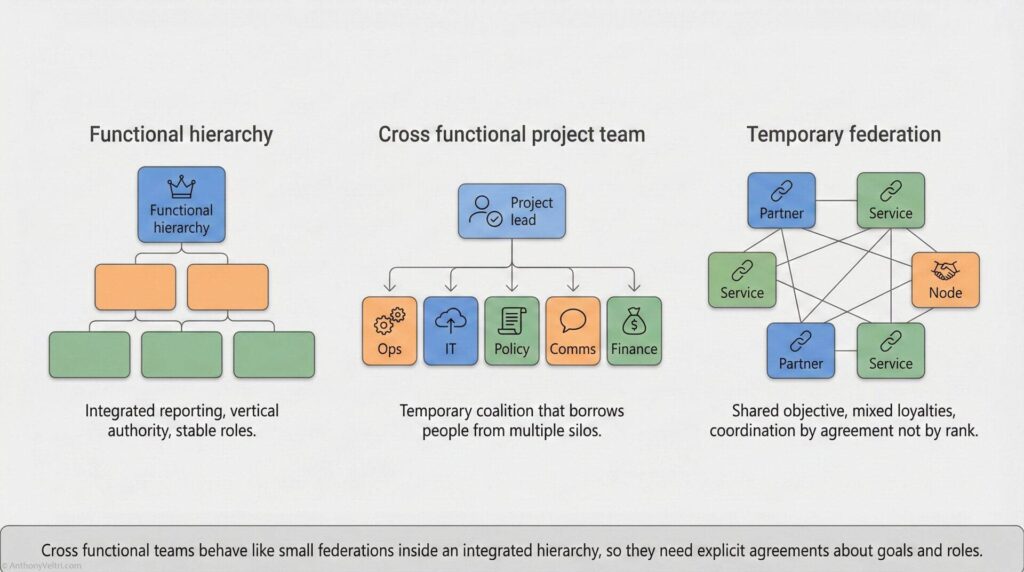

The Fire Network: The dispatch system isn’t a top-down hierarchy (Left). It is a Federated Network (Right) where Local, Geographic, and National nodes coordinate through shared agreements, not just command.

On the federal side we had all the usual markers:

- Agency badges and acronyms.

- Pre-printed vests and lanyards.

- Briefings that said “coordinate with local officials.”

Locals, on the other hand, had:

- Houses that were gone or unlivable.

- Family members scattered, missing or exhausted.

- Churches, parish halls and back rooms doing the work that formal shelters could not cover.

You could feel the difference when you walked into a county or parish building.

To a federal eye, it looked like a damaged office that needed support.

To the people who worked there, it was home turf. They had been there before the storm. They would be there after the federal surge left.

When we offered help, what people heard first was not the word “help.” They heard:

- Who are you.

- Who sent you.

- Who put you in my chain of responsibility.

If they did not have an answer they respected to those questions, the rest did not matter.

Sovereignty is not an abstract word

“Sovereignty” sounds abstract when you read it in a policy document.

It is not abstract when you sit across from a local official who is trying to protect their people and their authority at the same time.

In Bay St. Louis and nearby communities there was a clear pattern:

- Local and tribal officials had their own relationships and history with the federal government.

- They had seen promises come and go.

- They had lived through federal presence that felt more like surveillance or control than support.

So when we arrived with a federal map viewer and said, “Look, we can help you see everything,” it landed in a very specific context.

Sometimes the answer was:

“We will share this, but not that.”

Sometimes it was:

“We will work with you, but you do not get to own the story of what happened here.”

Sometimes it was quiet skepticism that you could only earn your way past by doing the boring work well and not disappearing when the cameras left.

What the maps could not show

The geospatial work mattered. It helped:

- Identify damaged infrastructure.

- Plan routes and staging.

- Give leadership a picture that was better than rumor.

But the maps could not show the thing that actually governed whether the work would stick:

- Who people trusted.

- Which relationships were already frayed.

- Where the line was between “support” and “taking over.”

There were moments where, technically, we could have pushed harder:

- We could have demanded more data.

- We could have pushed for more control of the picture.

- We could have treated local sovereignty as a problem to be managed.

Any time we even drifted near that posture, cooperation dropped.

The lesson was clear:

In a disaster, you are always working inside someone else’s sovereign space. If you ignore that reality because your logo is bigger, you will lose the trust you need to be effective.

Commitment over badges

What did people trust?

It was not the logo.

It was things like:

- Showing up when you said you would.

- Bringing back maps and products that reflected what locals told you, not just what the federal system expected.

- Admitting when you did not know something instead of improvising authority.

I remember quiet conversations in hallways and parking lots that had nothing to do with software. They were about:

- Where someone’s family was staying.

- Which street was actually passable even though the map said it was blocked.

- Who in town was the real decision maker, regardless of title.

Those conversations did more for our ability to support than any official briefing.

The pattern that followed me home

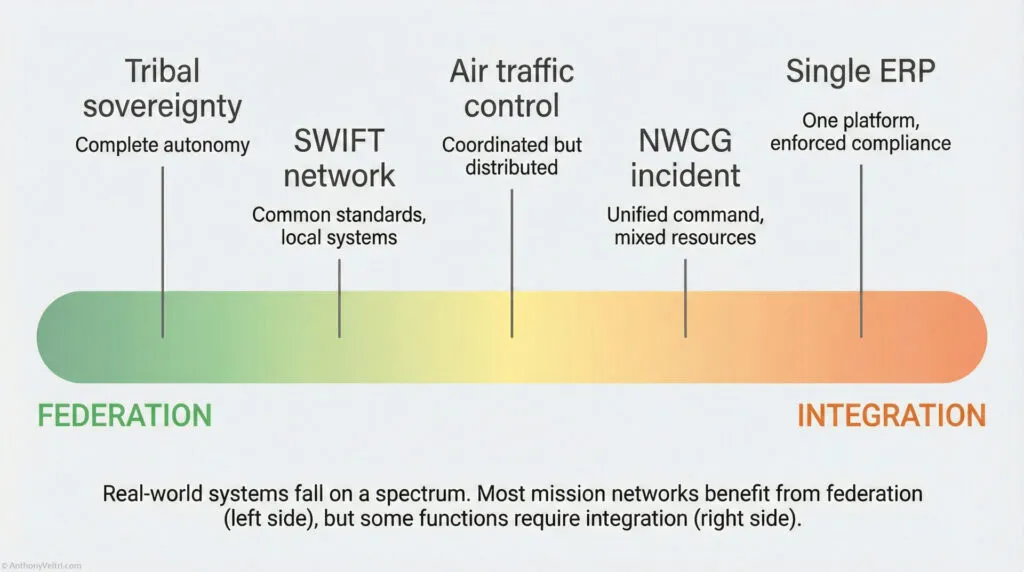

The fire system sits in the middle of the spectrum: “Coordinated but Distributed” just like Air Traffic Control. It balances local sovereignty with national power.

The Lesson: Successful systems are often integrated locally (for control) but federated globally (for scale). Finding the Balance: We couldn’t force “Single ERP” integration (Right). We had to operate at “Tribal Sovereignty” (Left) and earn our way toward the middle

Looking back, that Katrina deployment shaped a lot of how I think about federated systems and alliances.

A few things I took away:

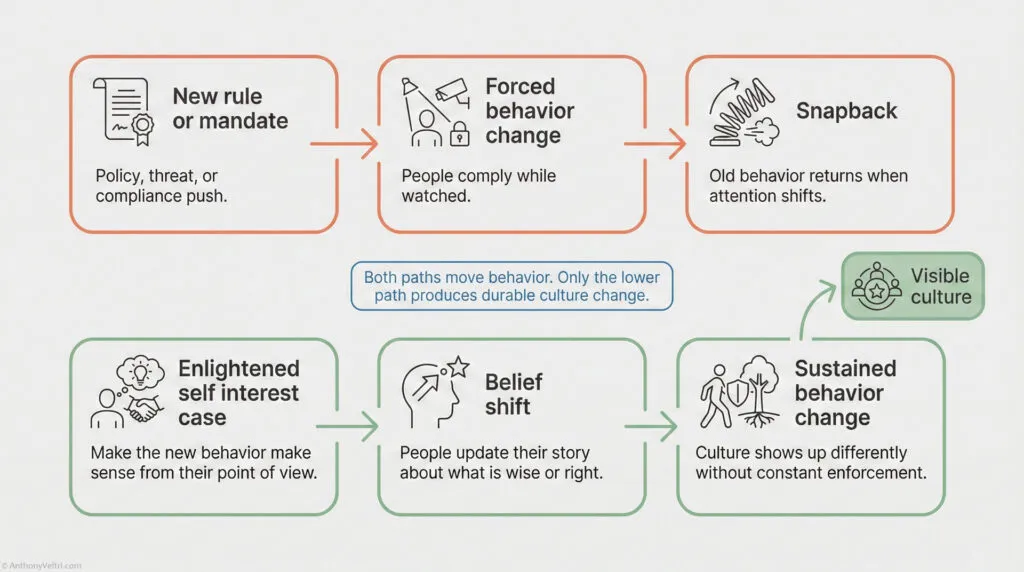

- Logos are not trust.

A federal badge opens a door. It does not keep it open. - Sovereignty is a real constraint.

Local, tribal, and state actors will decide how much of your help to accept. Sometimes “no” is the right answer for them. - Useful interoperability beats control.

It is better to have a map that is partially shared and trusted than a “perfect” common picture that people feel was taken from them. - Commitment shows up as small behavior.

Returning with updated maps when you promised to, calling when you said you would, not overstating what your tools can do.

These are not sentimental points. They are operational.

If you violate them, people stop sharing. When people stop sharing, your fancy integrated picture becomes a lie.

Why this matters to my work now

Later, when I worked on systems like iCAV and on civil-military programmes with former Warsaw Pact nations, I kept seeing the same pattern:

- Federated partners.

- Uneven data and tools.

- Deep histories with central authority.

- Very real stakes.

When I talk now about:

- Useful interoperability, not perfect interoperability

- Federated realities, shared outcomes

- Commitment over compliance

I am not speaking in abstractions.

I am thinking about specific rooms in specific towns that were already carrying more than their share, and how easy it would have been for us to break something important by treating trust and sovereignty as rounding errors.

If you are responsible for systems that depend on partners you do not control, you can buy software and write policy.

You still have to answer the same question I learned in Bay St. Louis:

“Do the people who live with the consequences actually trust you to be in the room?”

Last Updated on December 9, 2025