The structural principles that shape systems, reduce drag, absorb drift, and create resilience under real conditions #

Doctrine Claim: Architecture is not a set of diagrams; it is the set of structural decisions that determine how a system behaves under stress. This doctrine defines the boundaries, constraints, and evolution paths required to ensure the system accelerates the mission rather than bottling it up.

1. Purpose of the Architecture Doctrine #

Architecture is not technology.

Architecture is:

- structure

- boundaries

- constraints

- flow

- ownership

- intent

- interoperability

- cadence

- evolution paths

Architecture determines:

- what can scale

- what will break

- what becomes brittle

- what becomes resilient

- where drift will concentrate

- where autonomy is safe

- where centralization is required

Architecture is the design of everything that humans must operate within.

This annex defines the principles that make architecture a multiplier instead of a bottleneck.

2. What Architecture Actually Is #

Architecture is not diagrams, documents, or frameworks.

Architecture is:

The set of decisions that shape how the system behaves under stress.

Real architecture answers:

- What must be stable?

- What must be flexible?

- What must degrade gracefully?

- What must be federated?

- What must be centralized?

- What must operators control?

- What must leadership protect?

- Where does drift become dangerous?

Architecture is the guardian of coherence.

3. The Ten Architectural Principles #

These are the recurring architectural patterns that appear across your experience with iCAV, FRNs, and multi agency systems.

These define your architectural identity.

Principle 1: Federation Over Integration #

The Lesson: Successful systems are often integrated locally (for control) but federated globally (for scale).

Intent:

Let diverse systems remain diverse while still contributing to a unified operational picture.

Why:

Integration creates fragility. Federation creates resilience.

Example:

iCAV allowed partners to publish in their own formats. The federation layer harmonized them.

Failure mode:

Forced integration collapses under partner variation, legal differences, and political resistance.

Special Commentary:

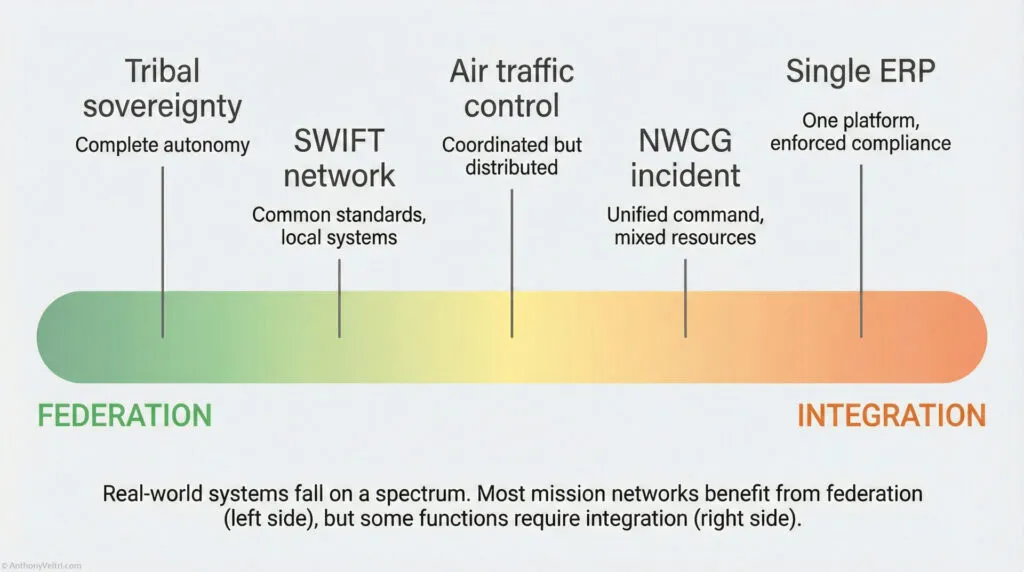

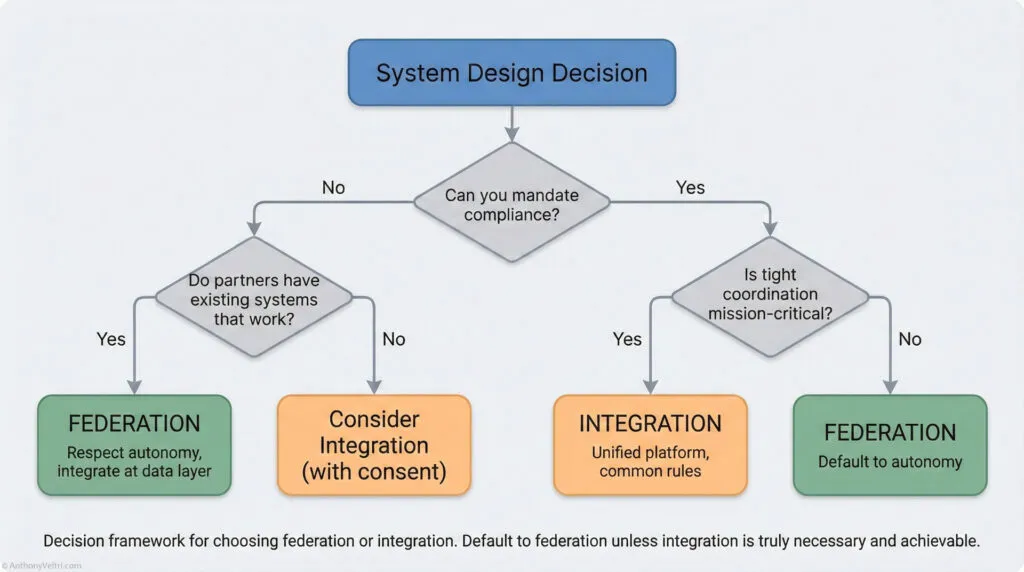

Federation vs integration is a spectrum, not a religion #

It is easy to turn “federation vs integration” into a binary. Integration is brittle, federation is resilient, end of story. Real systems are messier than that.

The question is not “integration or federation,” it is:

Given our mission, partners, and constraints, where on the spectrum do we belong, and what are we asking people to pay for that choice?

Full integration can work extremely well, but only when certain conditions are true.

- The mission is very focused and non-optional.

- Partners are willing to accept real cost and friction to align.

- There is a shared doctrine that is lived, not just published.

- Someone owns the standard, the interfaces, and the upgrade path.

That is why NWCG style integration can work. In wildland fire, partners are so committed to life safety and effective operations that they voluntarily accept common standards, common reporting, and tight coupling. They will change local tools and workflows, and even absorb painful transitions, because the shared mission justifies the cost. Tight integration of things like drone data, thermal imagery, and reporting is possible precisely because everyone agrees that the work is life and death and that common doctrine comes first.

On the other end of the spectrum are environments like iCAV at DHS, where you cannot force compliance. Tribal nations, state and local partners, and different federal components all have their own systems, legal constraints, and tempos. You do not get to rip and replace everything or demand that everyone land on one stack. There, federation is not a nice idea. It is the only survivable choice. You create a viewer and a set of contracts that can ingest and align what partners can actually send, at the quality and cadence they can realistically sustain.

The architecture job is to recognize which kind of world you are in for each interface and at each decision altitude, then choose the right level of integration or federation on purpose, instead of by fashion or habit. In some places you design for very tight integration and pay the price. In others you design for graceful federation and accept that the data is imperfect but the partnerships are durable.

Principle 2: Interfaces Break First #

Intent:

Design boundaries carefully because they are where systems fail.

Why:

Boundaries contain mismatched incentives and update cycles.

Example:

FRN workflow broke when leadership bypassed editorial and legal boundaries without warning.

Failure mode:

Unowned interfaces cause drift, conflict, and rework.

Principle 3: Every Interface Needs Two Owners #

Intent:

Prevent upstream and downstream teams from assuming the other will handle problems.

Why:

Two owners create clarity.

Example:

iCAV ingest stabilized when each partner feed had an upstream publisher and a downstream ingest owner.

Failure mode:

One sided ownership always produces blind spots.

Principle 4: Systems Must Degrade Gracefully #

Intent:

Systems should fail in slow, predictable, understandable ways.

Why:

All real systems face drift, outages, and partial information.

Example:

iCAV cached the last known good state, ensuring analysts were never blind.

Failure mode:

Binary systems collapse under minor deviation.

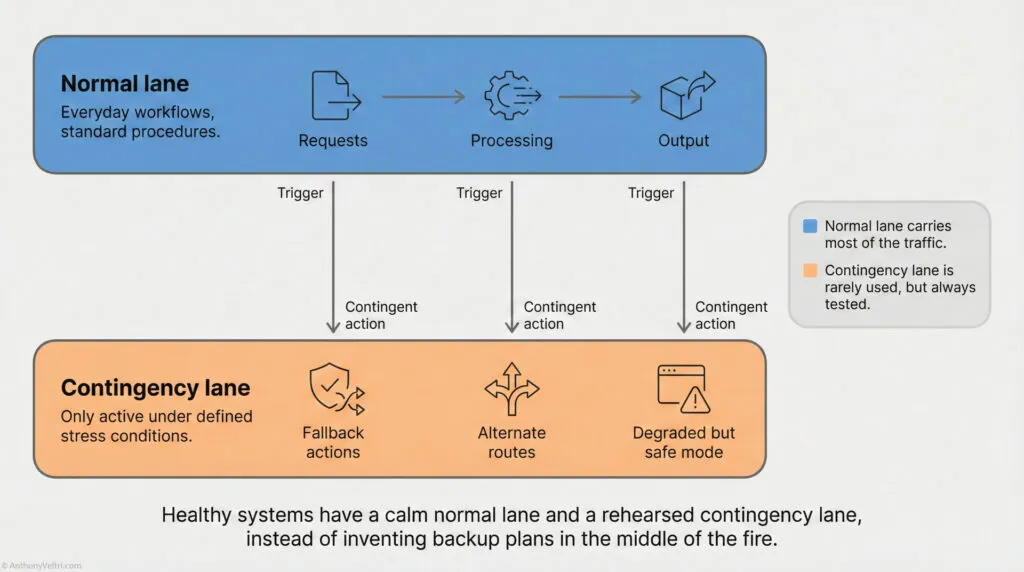

Principle 5: Prevention Defines Shape, Contingency Preserves Function #

Intent:

Architect both the rules and the fallback behavior.

Why:

Prevention without contingency is brittle. Contingency without prevention is chaos.

Example:

FRN workflows stabilized only when both rules and fallback were defined.

Failure mode:

Either extreme collapses under real conditions.

Principle 6: Constrain What Must Be Consistent, Free What Must Differ #

Intent:

Protect coherence without suffocating diversity.

Why:

Real environments require variation.

Example:

iCAV allowed partners to vary formats but constrained geometry, timestamps, and key fields.

Failure mode:

Over constraint creates resistance. Under constraint creates chaos.

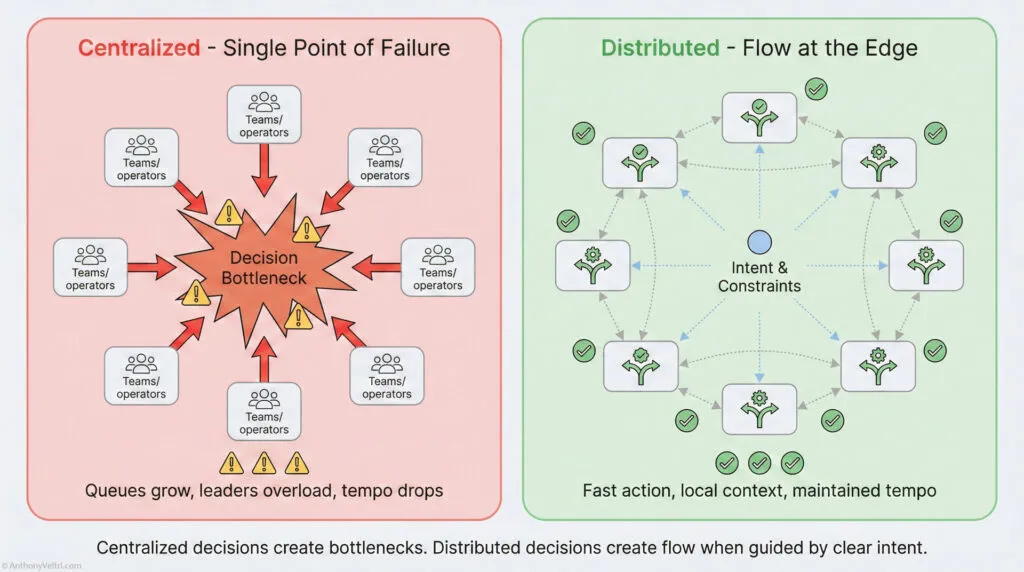

Principle 7: Architecture Exists to Reduce Decision Drag #

Intent:

Use design to reduce the number of decisions, escalations, and delays.

Why:

Decision drag multiplies cost. Architecture eliminates drag by removing ambiguity.

Example:

FRN schema stabilization reduced revision cycles dramatically.

Failure mode:

If architecture increases friction, it is not architecture. It is bureaucracy.

Principle 8: Architecture Enables Autonomy #

Intent:

Create a structure that allows people to act without fear.

Why:

Distributed decisions are only safe when the architecture supports them.

Example:

iCAV analysts moved quickly because ingest and display rules were predictable.

Failure mode:

If people wait for permission, the architecture is failing.

Principle 9: Architecture Defines the Evolution Path #

Intent:

Plan how systems and workflows will evolve over time.

Why:

Unplanned evolution creates drift and tech debt.

Example:

iCAV introduced new layers, new partner types, and new fallback modes through a predictable architecture driven evolution.

Failure mode:

Random evolution leads to fragmentation and brittle systems.

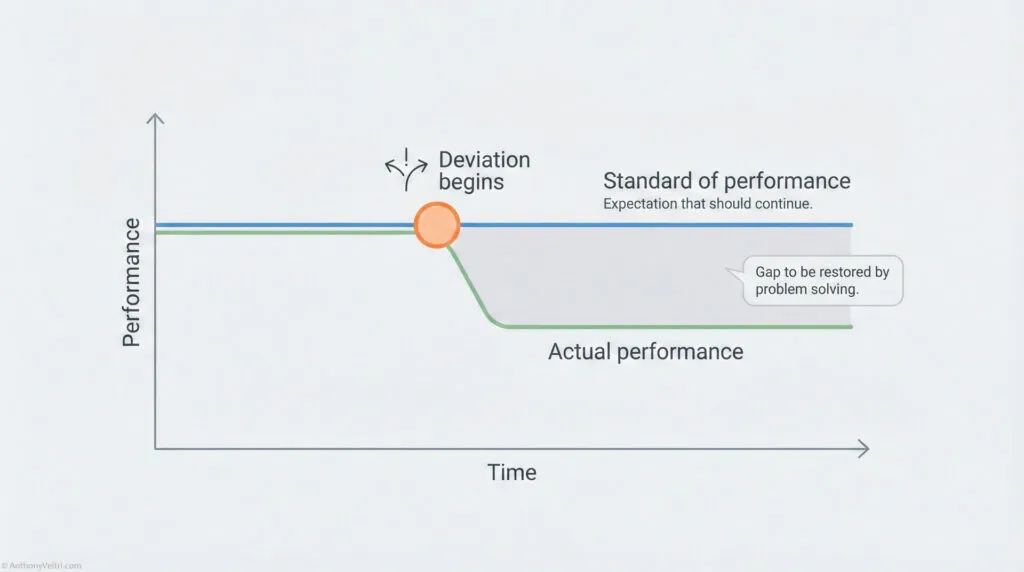

Principle 10: Architecture Manages Drift, It Does Not Pretend to Eliminate It #

Intent:

Expect drift. Design for drift.

Why:

Systems, humans, partners, and politics all drift.

Example:

FRN workflows drifted constantly until the architecture stabilized definitions, boundaries, and fallback rules.

Failure mode:

Pretending drift does not exist leads to catastrophic surprise.

4. Architecture Failure Modes #

Common architectural errors include:

Failure Mode 1: Over centralization #

Single points of failure. Fragility.

Failure Mode 2: Inconsistent boundaries #

Confusion, rework, conflict.

Failure Mode 3: No fallback #

Total failure during surprises.

Failure Mode 4: No versioning #

Silent drift destroys systems.

Failure Mode 5: Hidden assumptions #

Teams operate with contradictory mental models.

Failure Mode 6: Architecture by committee #

No coherence. No clarity. No ownership.

Failure Mode 7: Architecture that punishes action #

People freeze instead of move.

5. Architecture Success Modes #

Architecture succeeds when:

- constraints are clear

- fallback is defined

- interfaces have owners

- boundaries are respected

- decisions match altitude

- partner diversity is embraced

- systems degrade gracefully

- operators can act safely

- leaders maintain intent

- drift is detected early

A successful architecture is not elegant.

It is survivable.

6. Examples of Architecture Doctrine in Action #

FRN Example: Architectural design prevented leadership driven drift #

By locking the schema, stabilizing roles, defining fallback, and clarifying boundaries, the FRN workflow transformed from chaotic to predictable.

This was architecture, not project management.

iCAV Example: Federation as a foundational architectural decision #

iCAV’s architecture accepted:

- diverse formats

- diverse partners

- diverse cadences

and provided:

- harmonization

- caching

- degraded mode

This design choice created resilience.

7. Architecture Operating Template (Paste Ready) #

Architecture Decision Template

Purpose:

Describe what this architectural decision must achieve.

Boundary:

What this decision affects.

Constraints:

What must stay stable.

Freedom:

What can vary safely.

Fallback:

What happens during degraded conditions.

Interface Owners:

Upstream:

Downstream:

Versioning:

Major or minor change.

Deprecation plan.

Altitude:

Architecture operates at Altitude 3.

Impact:

Local, cross team, system wide.

Risks:

Drift, fragility, overload.

8. Cross Links #

Architecture Doctrine reinforces:

- Annex A: Human Contracts

- Annex B: Data Contracts

- Annex C: Interface Ownership

- Annex E: Prevention–Contingency Matrix

- Principle 7: Interfaces Break First

- Principle 10: Degraded Operations

- Principle 12: Emergent Resilience

- Principle 14: Decision Drag

- Principle 18: Preventive–Contingent Design

- Principle 20: Leadership vs Management vs Supervision

Architecture is the structural domain that makes leadership possible and operations survivable.

9. For Reflection: #

Ask yourself:

Where is the architecture unclear?

Where are the boundaries vague?

Where is fallback undefined?

Where is drift unmanaged?

Where is decision drag growing?

Fix the architecture.

Stabilize the system.

Protect the mission.

Last Updated on December 5, 2025