Why boundaries fail first and why every interface needs a clear owner on each side #

This page is a Doctrine Guide. It shows how to apply one principle from the Doctrine in real systems and real constraints. Use it as a reference when you are making decisions, designing workflows, or repairing things that broke under pressure.

Systems rarely fail in the middle. They fail at the edges. #

In every complex system, the most fragile point is not the core.

It is the boundary:

- between teams

- between systems

- between data sources

- between authorities

- between timelines

- between contracts

- between assumptions

Interfaces are fault lines.

They break first, break quietly, and break asymmetrically.

If you do not define them (and assign ownership) your system becomes a chain held together by hope.

Lived Example: The partner feed that “worked” but never lined up #

During an activation, a partner agency insisted their feed was publishing correctly.

Technically, they were right.

Their service endpoint was available.

It returned valid data.

There was no error on their side.

But it failed at the interface:

- their geometry was misaligned

- their schema did not match our expectations

- their timestamps drifted

- their refresh rate was lower than advertised

- their service intermittently returned partial sets

Everything inside their system worked.

Everything inside our system worked.

The failure was at the boundary.

There was no shared contract.

There was no shared owner.

There was no shared understanding of what “working” meant.

Once we defined the interface contract, the failure disappeared.

Interfaces break first.

Architects fix the boundaries.

Business Terms: Why interfaces matter #

Interfaces matter because:

- this is where misunderstandings hide

- this is where assumptions collide

- this is where scope slips

- this is where partners blame each other

- this is where timelines misalign

- this is where escalation begins

- this is where trust erodes

Inside teams, communication is usually strong.

Across teams, communication becomes filtered, delayed, and political.

Interfaces are where leadership must pay attention.

System Terms: What an interface actually is #

An interface is:

- a boundary

- a contract

- a promise

- a data structure

- a behavioral expectation

- a refresh rate

- an authentication model

- an error handling agreement

- a versioning plan

Interfaces are agreements, not pipes.

When architects fail to define them:

- coupling increases

- ambiguity grows

- error cascades multiply

- drift accumulates

- failure detection becomes slow and expensive

- ownership becomes contested

Every poorly defined interface becomes a long term problem.

Why Interfaces Fail #

Business perspective #

Interfaces fail because:

- expectations differ

- success is defined differently

- teams assume “the other side” will adjust

- responsibilities are unclear

- authorities overlap

- timelines mismatch

- communication breaks down

- nobody wants to own problems that originate “outside”

A system without explicit interface ownership collapses into finger pointing.

System perspective #

Interfaces fail because:

- schemas drift

- formats evolve

- time stamps misalign

- refresh rates change

- update cadences differ

- error states are undocumented

- retries are poorly understood

- authentication rotates without warning

- hidden assumptions compound over time

Interfaces fail because systems evolve.

Contracts prevent that evolution from becoming chaos.

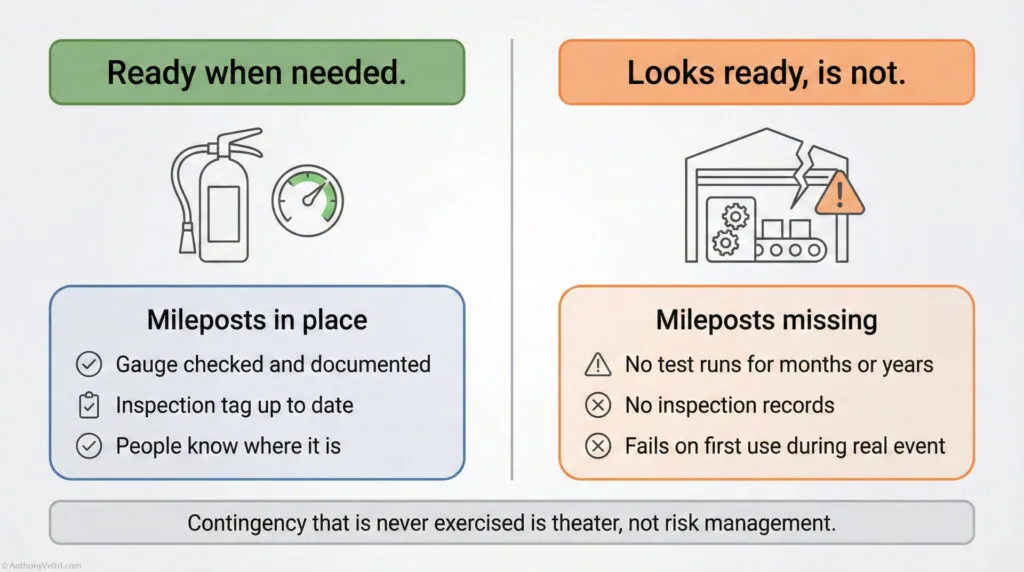

Why Contracts Fix Interfaces #

An interface contract clarifies:

- what each side promises

- what “working” looks like

- what tolerances exist

- what versioning means

- what happens when something breaks

- who responds first

- what “stable” means during activation

- what minimum viable publication looks like

- what “we will fix it after the storm” actually means

Without contracts, both sides act on wishful thinking.

With contracts, both sides act on shared expectations.

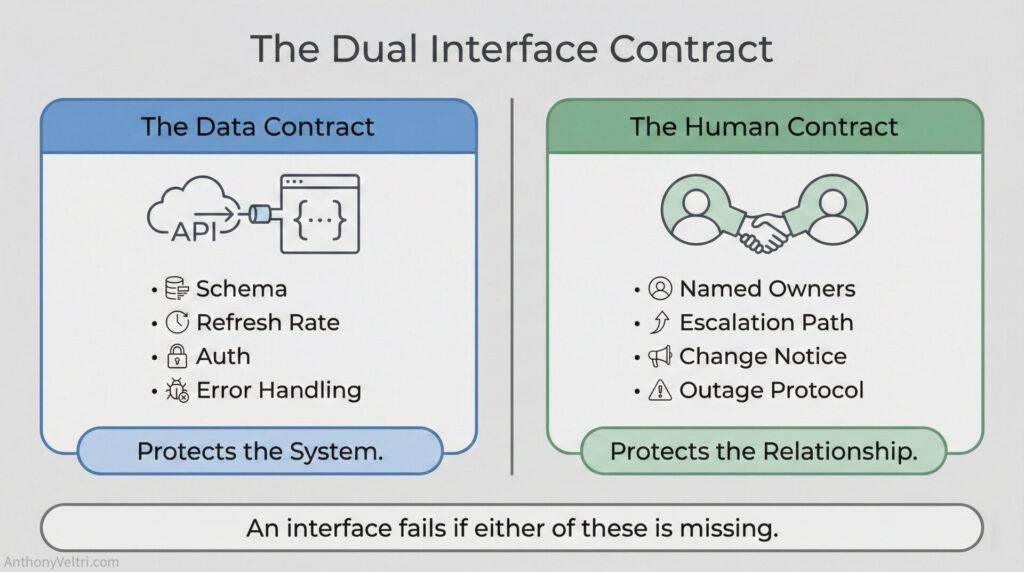

Two Types of Interface Contracts #

You will use both in your doctrine.

1. Data Contract #

Defines the technical and behavioral boundary.

Must include:

- schema

- attributes

- geometry expectations

- refresh rate

- time stamping rules

- authentication method

- fallback behavior

- error handling

- versioning

- minimum viable publication

This contract protects the system.

2. Human Contract #

Defines the responsibilities and roles between people.

Must include:

- who owns the feed on their side

- who owns the ingestion on our side

- how we escalate

- how we communicate during outages

- how we announce changes

- how we interpret urgent needs

- what autonomy each side has

- what cannot be changed during an activation

This contract protects the relationship.

Both are required for resilient systems.

Business Example: Two owners solved what six months of calls could not #

A multi agency integration stalled for months because:

- engineers talked only to engineers

- managers talked only to managers

- leadership talked only to leadership

Nobody owned the interface together.

We established a two owner model:

- one owner on their side

- one owner on our side

- weekly sync

- shared definition of success

- shared versioning agreement

- shared change log

The integration completed in three weeks.

Interfaces do not need committees.

They need owners.

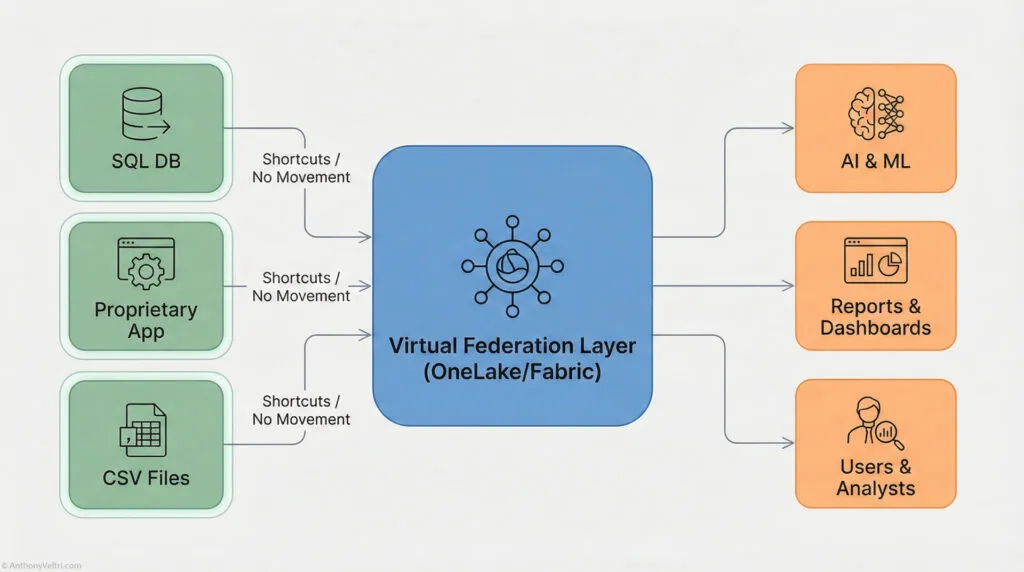

System Example: The iCAV harmonization layer saved dozens of broken interfaces #

In iCAV:

- some feeds were too slow

- some were malformed

- some were insecure

- some used legacy projections

- some included garbage geometry

- some missed critical fields

Rather than forcing integration, we created:

- harmonization patterns

- tolerant parsing

- schema mapping

- confidence scoring

- caching

- fallback modes

- partner specific connectors

Each connector acted as a controlled interface boundary with:

- explicit expectations

- explicit behavior

- explicit ownership

This prevented the entire system from collapsing under diversity.

Architect-Level Principle #

As an architect, I treat interfaces as the most fragile part of the system.

I define contracts.

I assign owners.

I design boundaries so failures stay local and do not cascade.

Twenty Second Takeaway: #

“Systems do not fail in the center. They fail at the boundaries between teams and systems. I define clear interface contracts and assign owners on each side so that ambiguity does not become failure. That is how I prevent small issues from turning into systemic outages.”

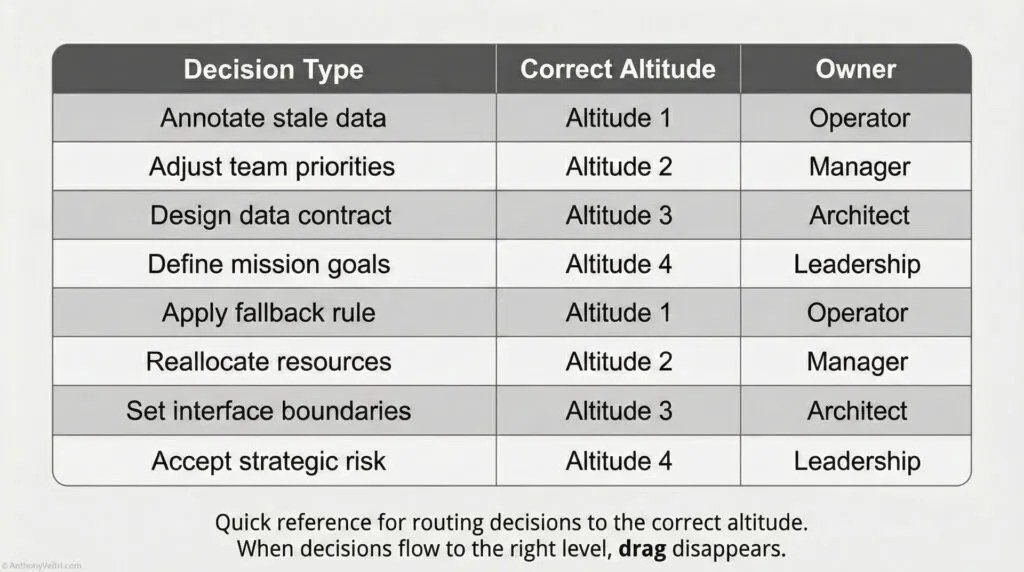

Cross Links to Other Principles #

Interfaces connect tightly with:

- Useful interoperability

- Federation

- Two lane systems

- Emergent resilience

- Degraded operations

- Decision drag

- Technical debt as leadership signal

- Distributed decisions

Interfaces are the friction points that every other principle supports.

Doctrine Diagnostic – For Reflection: #

Ask yourself:

Where are your system’s true boundaries?

Do they have owners?

Do they have contracts?

If not, that is where failure will begin.

Define the boundaries before they define the failure.

Field notes and examples #

- Why Ledger/Visibility Collapse is everywhere in 2026

- Field Note: Sorting the 20-Year Backpack

- The Loudest Listener: When Interviews Become Something Else

- Field Note: Defining “Operator”

- Why I Kept Quiet: A Field Note on the Stewardship of Operational Knowledge

- Field Note: The 1790 Farmhouse and What It Taught Me About Stewardship

- Hoover Dam Lessons: “Proudly Maintained By Mike E.”

- Culture As Invisible Spec: Training A Media Specialist For Wildland Fire

- Interfaces Break First: Designing For Partial Truth

- Living With Incomplete Pictures: Notes From High Tempo Systems

Last Updated on February 22, 2026