Documentation as Credibility Infrastructure

Or: Why Tacit Knowledge Fails When You Need It Most

I can execute complex work. I’ve been doing it for 20 years across disaster response, federal systems architecture, and forward-deployed operations. The capability is real. The track record is documented in systems that still run, after-action reports, and infrastructure that absorbed actual pressure.

But recently, I had to confront an uncomfortable truth. Good work does not speak for itself.

For years, I believed it did. I suffered from the specific hubris of the technical expert. I had the arrogance to think that if the engineering is sound, the adoption will follow. I learned the hard way that this is false.

Before Hurricane Katrina, I developed a mobile mapping unit concept. It was technically superior to the existing solutions. It solved the exact problems we faced in the field. When the storm hit, I deployed with it alongside the Rhode Island Urban Search and Rescue Task Force. We used it in the ruins. It worked. It received great acclaim from the operators who relied on it.

I looked at that accomplishment and thought, “I will not need marketing. Marketing is beneath me. The engineering and the science are so good that they will speak for themselves.”

That was not the case.

Despite the field success and the technical validation, I struggled to sell it. I struggled to get adoption. I thought the problem was them. I thought they just didn’t get it.

The problem was me. I was hoarding the logic of the solution in my head. I expected others to intuitively grasp the years of tacit knowledge that led to that specific design. I hadn’t built the bridge for them to cross.

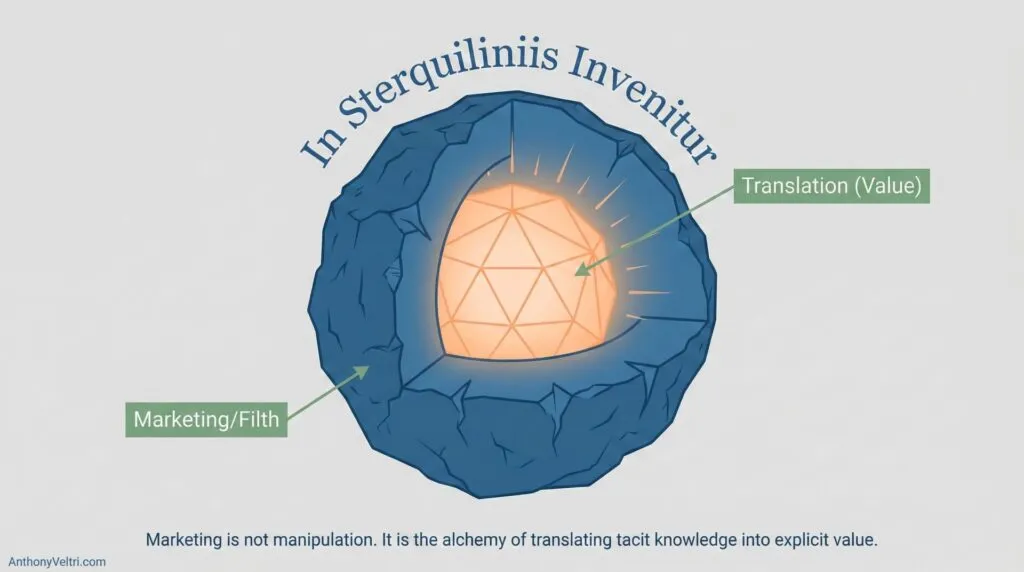

“In Filth It Will Be Found”

There is an old alchemist maxim, In sterquiliniis invenitur. It translates to “In filth it will be found.” It means that the thing you most need is often hidden in the place you least want to look.

For me, that place was marketing.

As a scientist, I viewed marketing with suspicion. It felt like noise. It felt like manipulation. But when I finally looked at it out of necessity, I realized that marketing isn’t just about selling. It is about translation. It is the discipline of taking what is in your head, the tacit, and making it usable for someone else, the explicit.

Science is mute without it. Operations are invisible without it.

Why (almost) No One Wrote Down How to Sharpen a Scythe

This problem isn’t unique to me. It is a historical pattern. When scythes were the primary tool for cutting grain or straw, the transmission of how to sharpen them was almost entirely oral and kinetic. It wasn’t that the skill was trivial. A dull scythe is useless. But it was so common among the user base that documenting it felt redundant.

Then tractors took over. The oral tradition broke. Now, people trying to revive the tool struggle to relearn techniques that were once universal. The knowledge didn’t disappear because it was secret. It disappeared because it was tacit.

This is the pattern. When knowledge is locked in the operator’s head, it feels unnecessary to document until the operator is gone.

The Scalpel and the Swiss Army Knife

This issue is particularly acute for a specific type of operator: the Solo Integrated Operator.

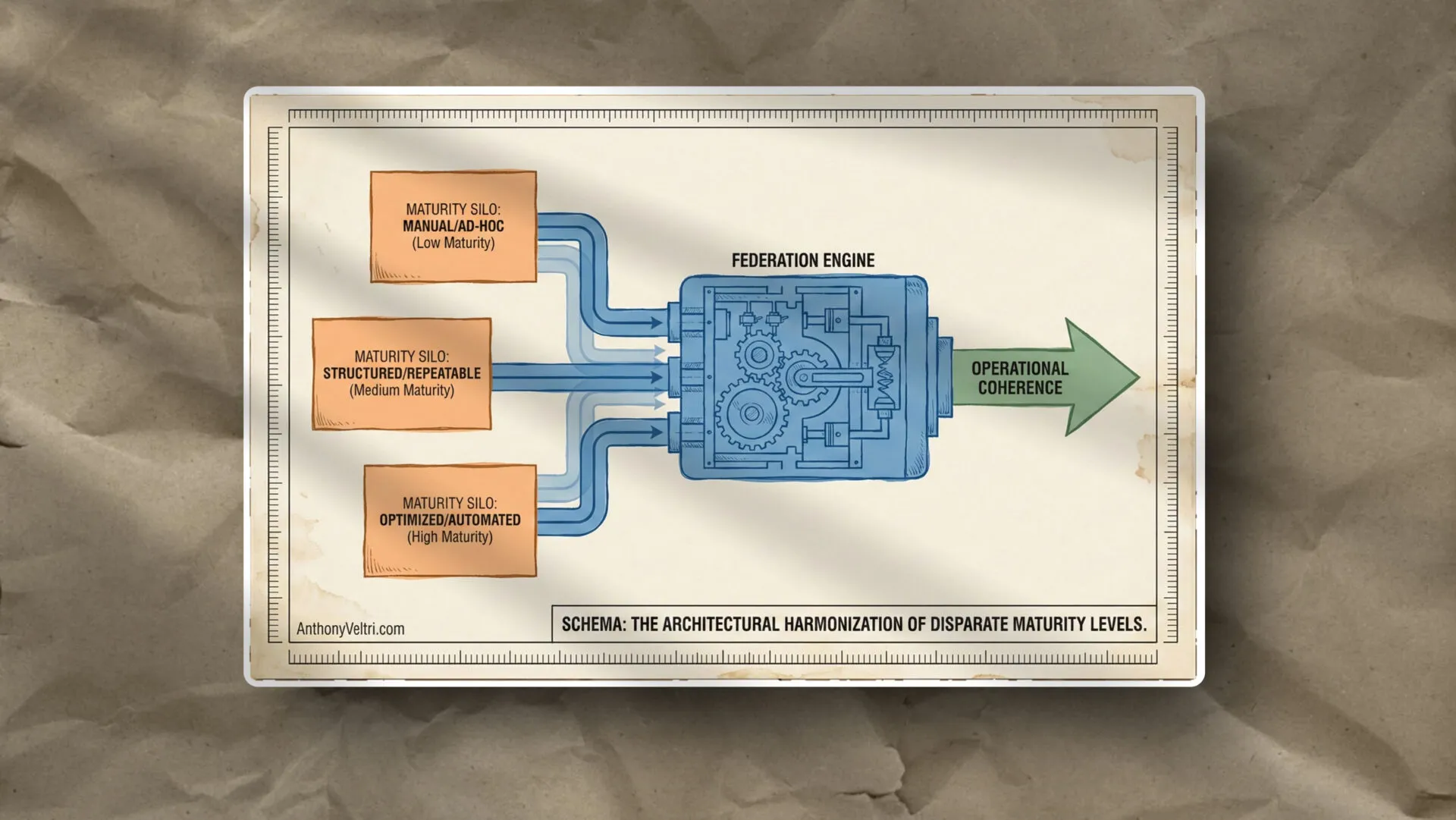

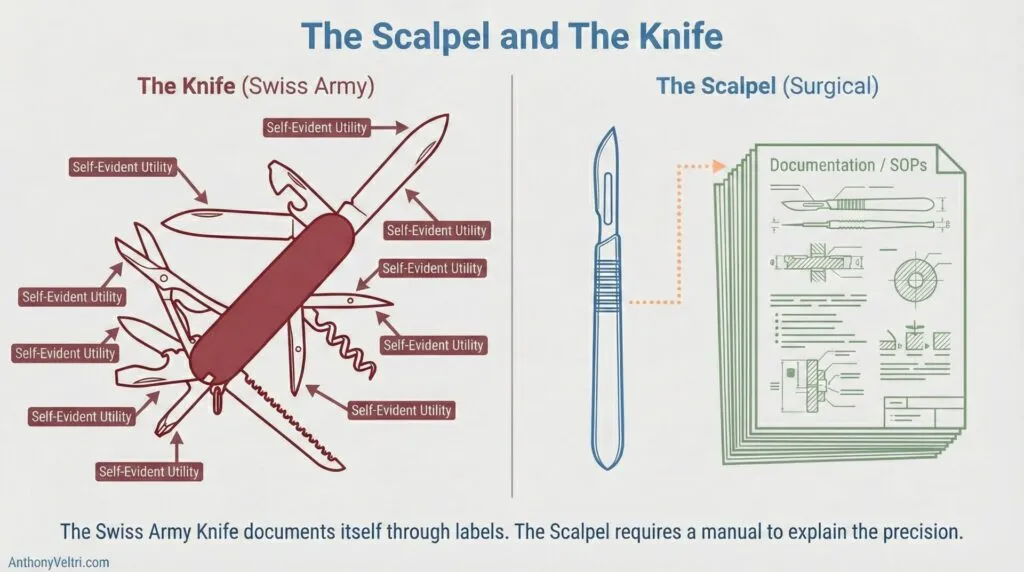

I’ve written before about the difference between the Scalpel and the Swiss Army Knife. It is critical to understand that one is not superior to the other. They are designed for different purposes.

- The Swiss Army Knife (Federated): This is a team or a platform with distinct tools. You have a screwdriver, a blade, a file. Each part is labeled. It is self-documenting. You can hand it to a stranger and they can figure out which tool does what. It is optimized for general utility and broad access.

- The Scalpel (Integrated): This is a single, unified instrument. In skilled hands, it operates with extreme velocity and precision. It cuts through complexity because there are no handoffs, no friction, and no meetings between the “handle department” and the “blade department.”

The problem is that a Scalpel looks like a simple piece of metal to anyone who hasn’t seen it used.

The Swiss Army Knife documents itself. The Scalpel requires the operator to explain why the cut was made there, how the angle was chosen, and what anatomy was avoided. Without that documentation, the Scalpel’s work looks like magic or luck. And you cannot scale magic (even with more magic).

The Four Stages of Disbelief

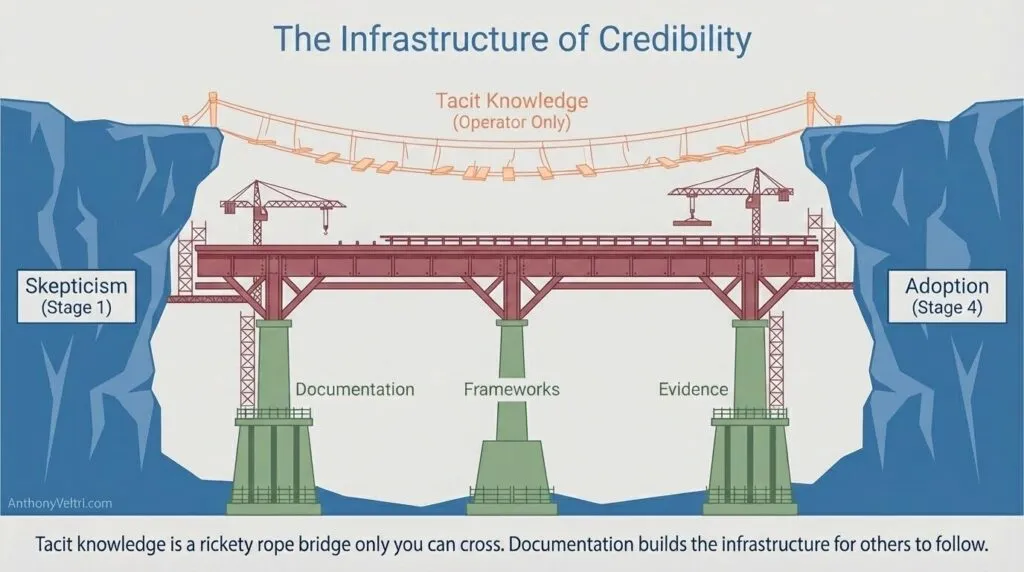

When you ask someone to trust a Scalpel without documentation, you are asking them to make an impossible leap. In marketing terms, you are asking them to skip steps in the “Trust Funnel.”

People generally move through four stages when encountering a new high-performance capability (or a new high-performance [something]):

- “It’s Impossible”: This doesn’t work. Ever. It can’t be done that fast. (or, it just can’t be done)

- “You’re Special”: Okay, you did it, but you’re a unicorn. It won’t work for anyone else.

- “Help Me”: It might work for me, but only if you are standing right next to me.

- “I Believe”: I understand the system. I can apply the principle myself.

Tacit knowledge keeps people stuck at Stage 2. They see the result, but they attribute it to you, not the method.

Documentation is the infrastructure that moves them to Stage 4. It shows them that the result wasn’t a magic trick. It was a process.

Artifacts of Evidence: What Credibility Looks Like

So, what does this actually look like? If you are a solo operator, you can’t just rely on your resume. You need to produce Artifacts of Evidence that act as a proxy for your presence.

It isn’t just “writing things down.” It is building specific types of assets:

- The Architecture Diagram: Not just the final state, but the “Why.” Show the constraints you accepted and the ones you rejected.

- The Decision Log: A record of the pivots. “We chose X over Y because of Z.” This proves your intuition is actually data-processing, not guessing.

- The Post-Mortem: A ruthless analysis of a failure. Vulnerability creates more credibility than perfection.

- The Framework: Turning a “gut feeling” into a named model, like “Federation vs. Integration.” This gives others a handle to carry your idea.

The Four Dialects of Documentation

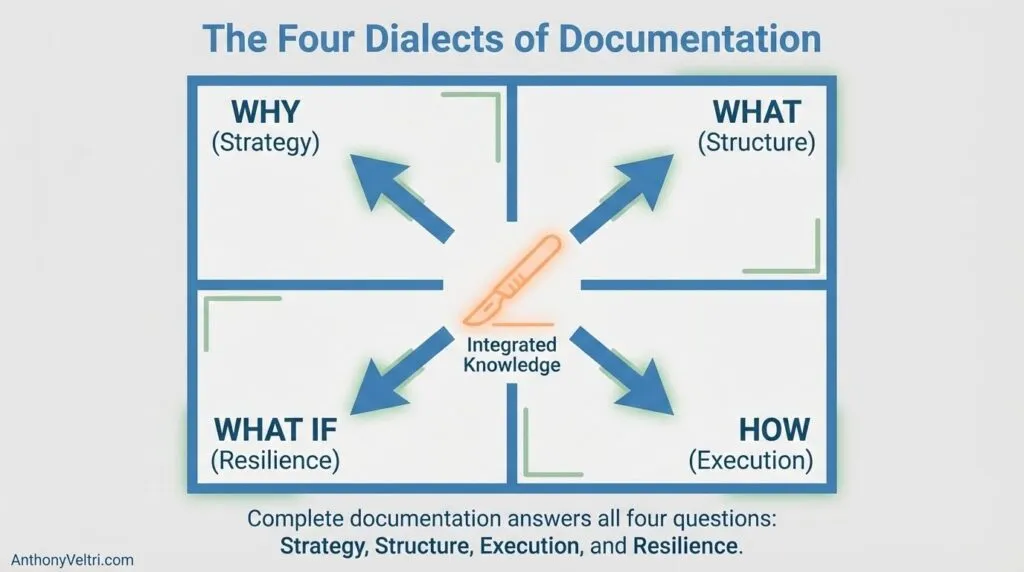

To build a complete bridge across the trust gap, your documentation cannot just speak one language. It must address the four distinct cognitive styles that people use to evaluate new information.

In instructional design, this is often broken down into the Why, the What, the How, and the What If.

As a solo operator, you likely integrate these four perspectives instantly in your head. But your audience does not. If your documentation misses one, you lose that segment of your audience.

1. The Why (The Strategist)

- The Question: “Why is this important? Why did we choose this path over another?”

- The Document: The Decision Log and the Problem Statement.

- The Risk: If you miss this, people see your work as just “technical tinkering” rather than a strategic asset.

2. The What (The Analyst)

- The Question: “What is this made of? What are the facts? What is the history?”

- The Document: The Architecture Diagram and the Tech Stack Inventory.

- The Risk: If you miss this, people cannot evaluate the structural integrity of your work. It looks like a black box.

3. The How (The Operator)

- The Question: “How does it function? How do I press the buttons?”

- The Document: The Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) and the Runbook.

- The Risk: If you miss this, the system becomes a “magic artifact” that only you can wield. This is where the “bus factor” is highest.

4. The What If (The Risk Manager)

- The Question: “What if this breaks? What if we scale? So what happens next?”

- The Document: The Post-Mortem, the Scaling Plan, and the Contingency Protocols.

- The Risk: If you miss this, people think you are naive. They think you haven’t considered the failure modes.

The “Scalpel” fails when it only documents the How. You hand someone a manual on how to cut, but you never explain Why the surgery is necessary or What If an artery is nicked.

Credibility comes from answering all four questions before they are asked.

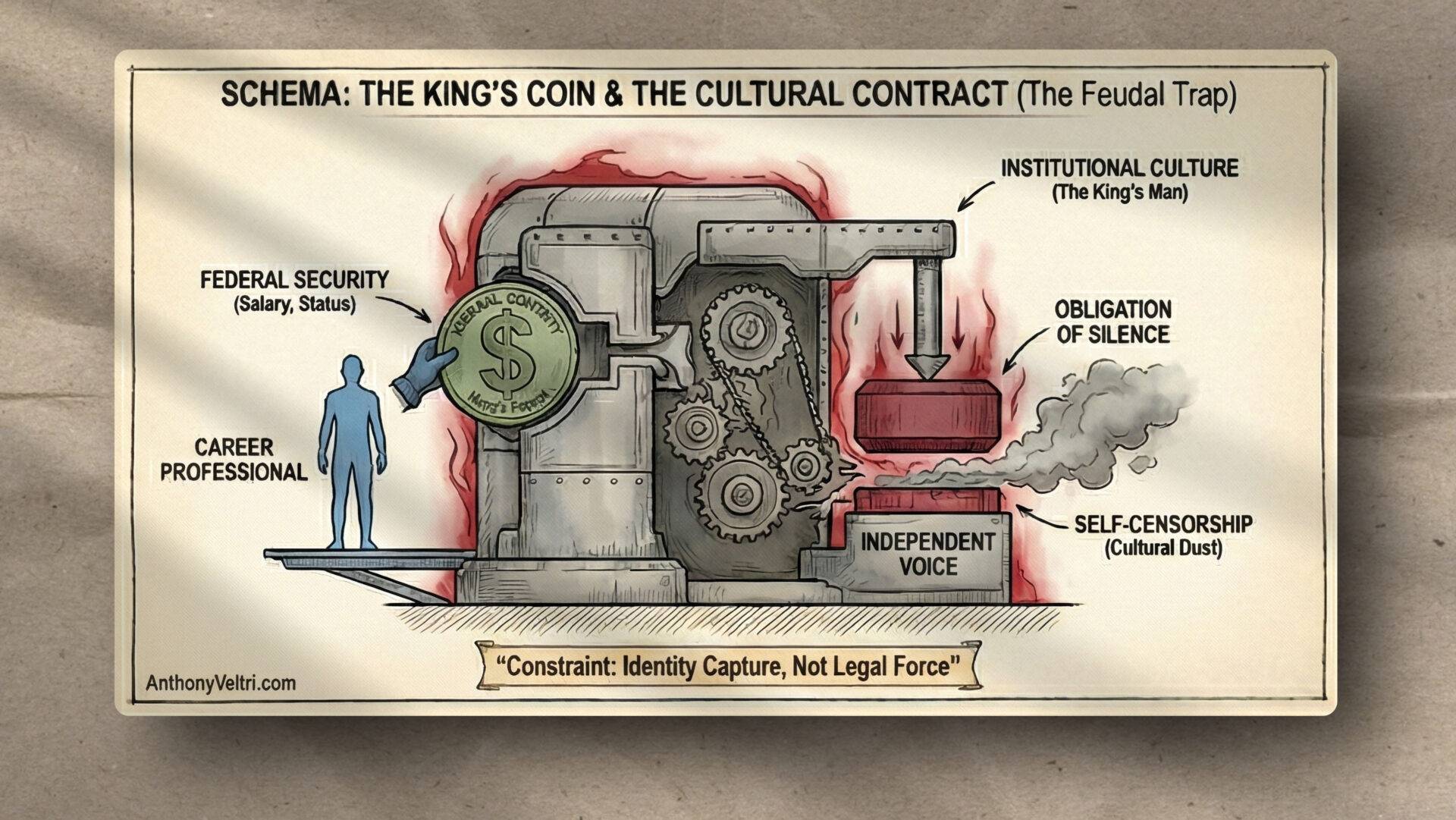

The Doctrine Point

If you are a Scalpel, comprehensive documentation isn’t overhead. It is your interface.

The Swiss Army Knife has labels on the tools. You do not. You have to build the manual.

I am building comprehensive documentation of patterns I’ve used for 20 years not because I am looking for a job, but because I realized that tacit knowledge has a “bus factor” of one (one person).

If I get hit by a bus tomorrow, the capability shouldn’t die with me (the bus factor). The “filth” I had to wade through was admitting that my work didn’t speak for itself. I had to speak for it. And now, I am writing it down so it can speak for itself when I am not there.

Documentation is credibility infrastructure. It turns invisible capability into verifiable assets.

Last Updated on December 16, 2025