Field Note: Compass-X Recognition Patterns and Strategic Framing

Scene

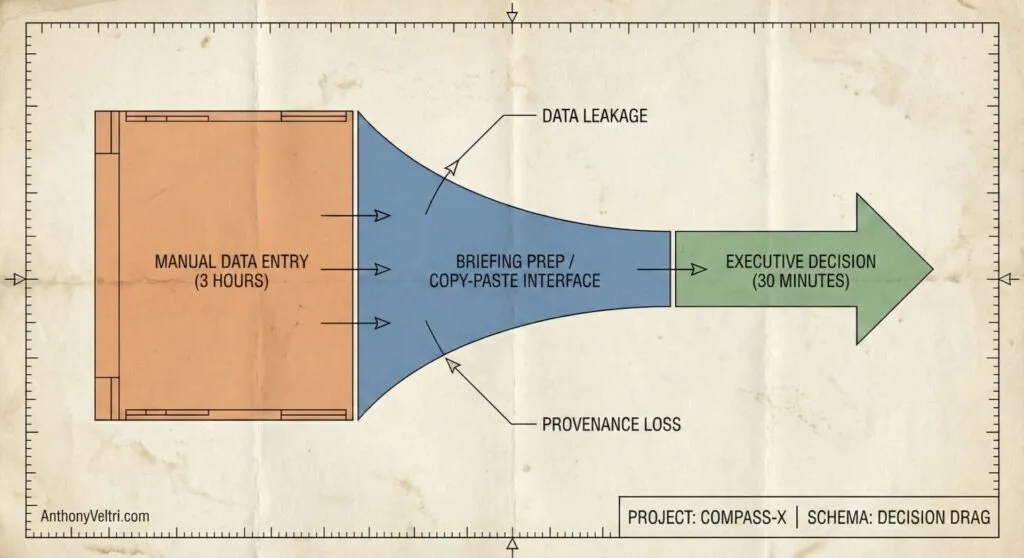

I have sat in too many conference rooms where a GS-15 or Senior Executive asks their team: “Why can’t the dashboard just show us this?” and someone mumbles “We’re working on it” and everyone moves on. I have sat in rooms where teams of GS-14s and GS-15s spend three hours preparing briefing materials for their slice of the portfolio, knowing this same process is happening simultaneously in other offices for their slices, and knowing the entire coordination cycle will repeat at the next hierarchical level when it moves from under secretary to secretary. High-grade functionaries doing manual aggregation and copy-paste work. It shouldn’t have to be this way. This happens weekly, sometimes more frequently. Sometimes I was one of those people.

This is not consultant observation. This is direct experience.

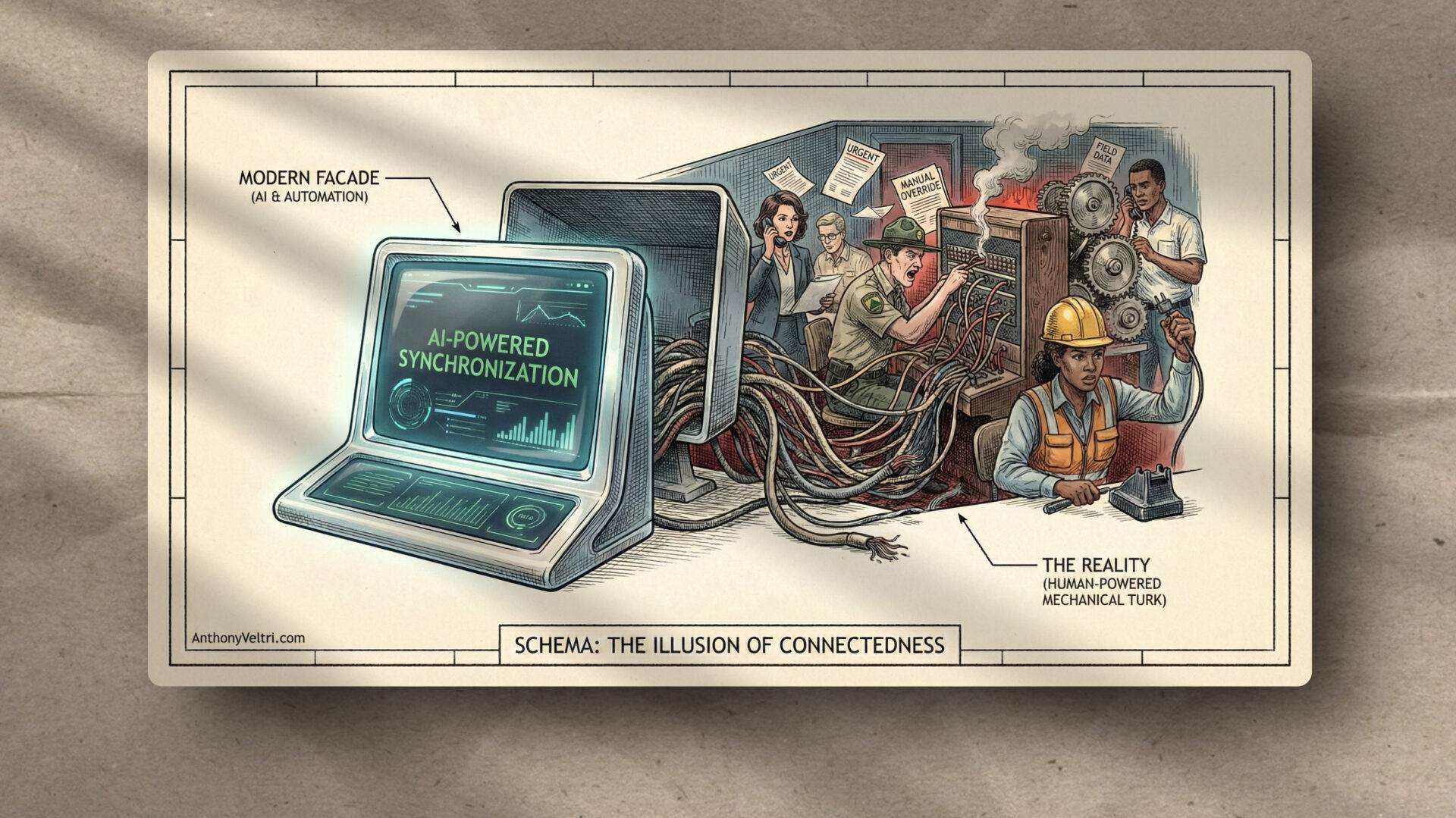

I have been the person asking “Why doesn’t Microsoft do this out of the box?” and gotten the shoulder shrug that means “That’s just how it is.” I have watched talented developers build SharePoint automation that works brilliantly within one office, only to collapse the moment it has to interface with another office using default configurations. I have seen Shadow IT emerge not because people want to circumvent policy, but because the sanctioned tools cannot address the strategic visibility problem they face every day.

When I talk about Compass-X, I am describing infrastructure that solves problems I have lived through. What follows are the recognition patterns that repeat when people encounter this kind of federated portfolio architecture. These patterns reveal constraints, reveal context, and reveal whether an organization is operating in terrain where this infrastructure makes sense.

Break: The Strategic Frame

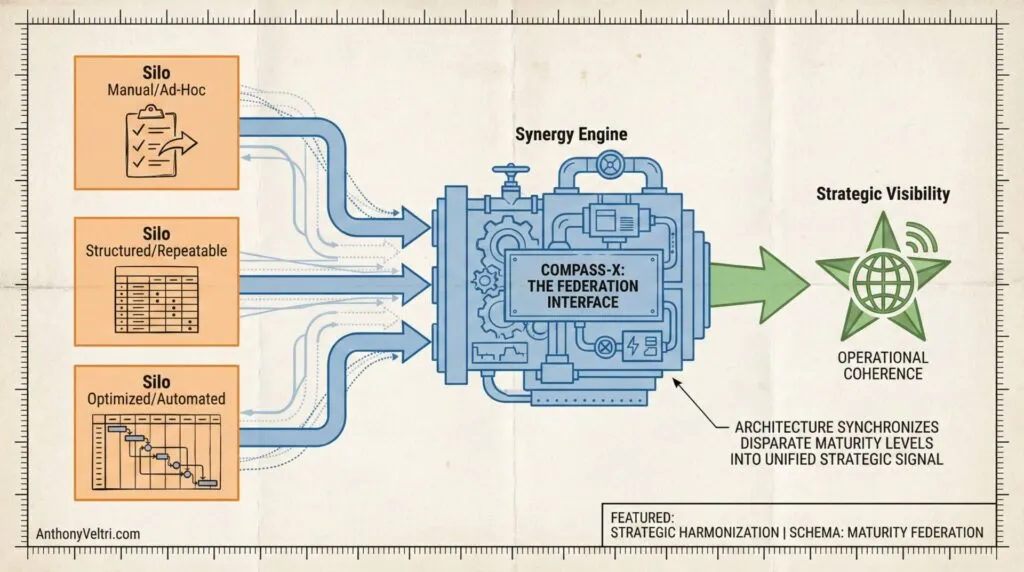

Compass-X Is Two Things Simultaneously

Deployed Pattern Library

Compass-X is operationalized portfolio architecture for M365. It is the federated PMO patterns from NASA’s JPL, packaged for deployment. Installation, operation, and team training all happen together. No rip-and-replace. No SaaS dependency. The organization owns everything.

This positioning matters because it sidesteps two common categorization traps: it is not a custom development shop building bespoke solutions, and it is not shrinkwrap software forcing conformity. It is repeatable patterns that adapt to existing organizational structure rather than forcing organizational structure to adapt to the tool.

Innovation Lane for Portfolio Strategy

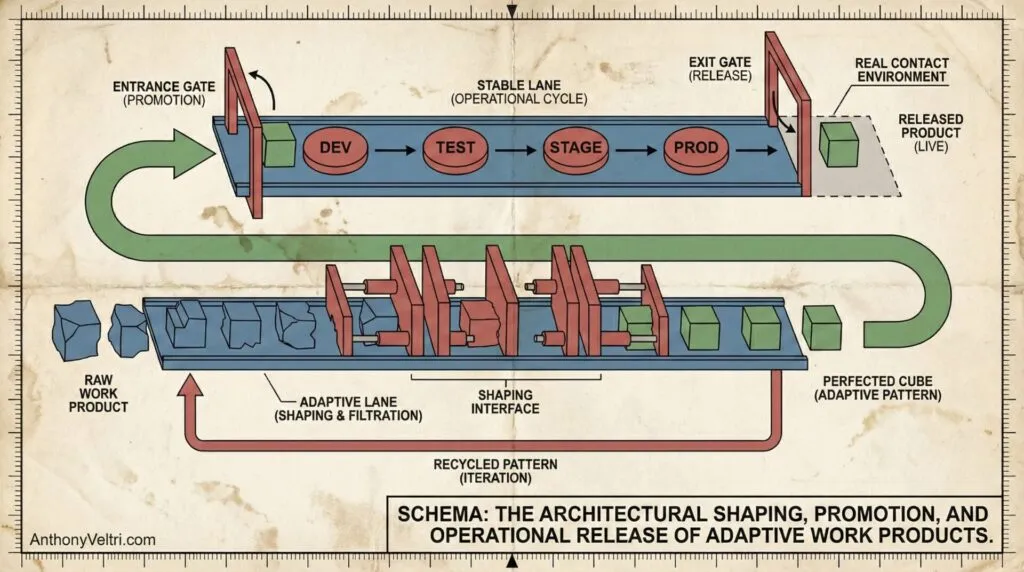

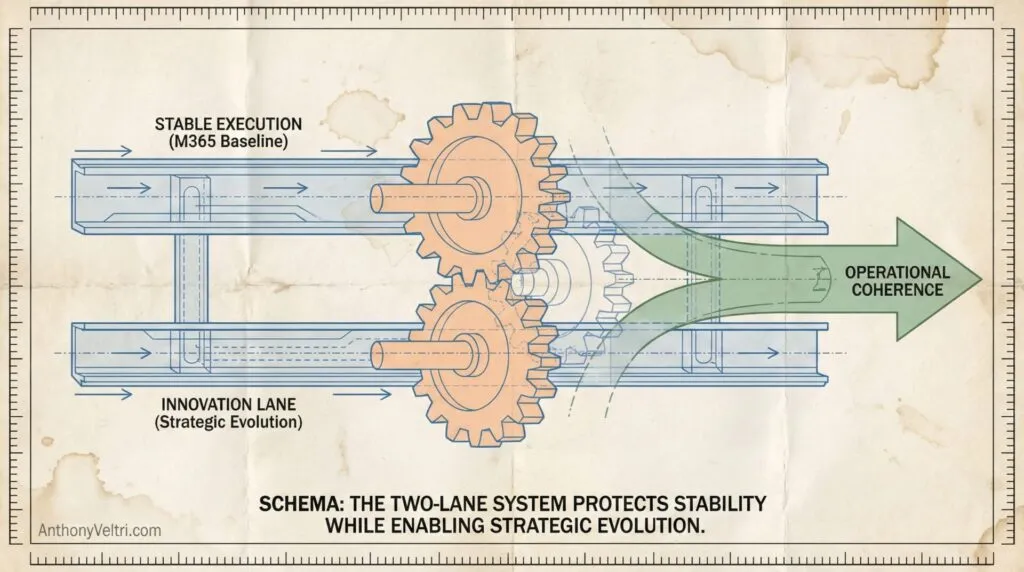

Most federal organizations operate with dev/test/prod environments designed for operational stability: pushing vendor-approved patches, deploying updates, and maintaining uptime. This is the stable lane where execution happens safely.

What typically does not exist: a parallel adaptive or innovation lane for strategic experimentation. A space to test portfolio views, try OKR alignment approaches, experiment with risk patterns, and democratize good ideas from the field without disrupting production systems.

Dev/test/prod serves stability. Strategic innovation needs its own lane.

Compass-X operates as that innovation lane. It runs on the existing M365 tenant, so there is no new ATO, no new vendor, and no risk to the stable lane. Projects execute in the stable lane: strategic insights emerge in the innovation lane.

This resonates with federal culture because it:

- Respects operational constraints (does not force risk on production systems)

- Enables strategic experimentation (addresses the actual need)

- Democratizes innovation (good ideas can be tested regardless of source)

- Works within existing authorities (no new vendor/ATO requirement)

- Separates concerns properly (stable execution vs. strategic evolution)

For deeper architecture principles on why two-lane systems matter, see Doctrine 06: A Two-Lane System Protects Stability and Enables Evolution.

Schema: Recognition Patterns

These are three questions that surface repeatedly when people encounter Compass-X. The questions themselves are diagnostic: they reveal the hidden constraints, the procurement history, and where the current operational pain lives.

Recognition Pattern 1: “Why Doesn’t Microsoft Do This Out of the Box?”

The question:

“Why doesn’t Microsoft just build this into Power BI or Project? We’re already paying them for E5 licenses.”

What this question actually reveals:

This is a question regarding Operational Tempo: the person asking recognizes that while Microsoft provides the blocks, the organization must decide how to stack them. They need the Internal Language (the technical logic) to explain why a federated architecture is the superior choice for procurement and leadership.

This is not actually a question about Microsoft’s product roadmap. People already know Microsoft will not suddenly release portfolio federation infrastructure next quarter. This has been a pain point for years and Microsoft shows no indication of addressing it. This is a strategic decision on Microsoft’s part, not a failing. Microsoft is not in the portfolio visibility business. They are in the building blocks business, the ingredient layer business. They are not running the restaurant: they are supplying the kitchen.

The question reveals something else: the person asking needs language to explain this decision internally. They need to understand the gap well enough to defend the choice to their boss, to procurement, to skeptics who will ask “why can’t Microsoft do this?”

The emotional state underneath:

The emotional state underneath is not skepticism: it is resignation. “This is just how it is. This is the way someone likes it.”

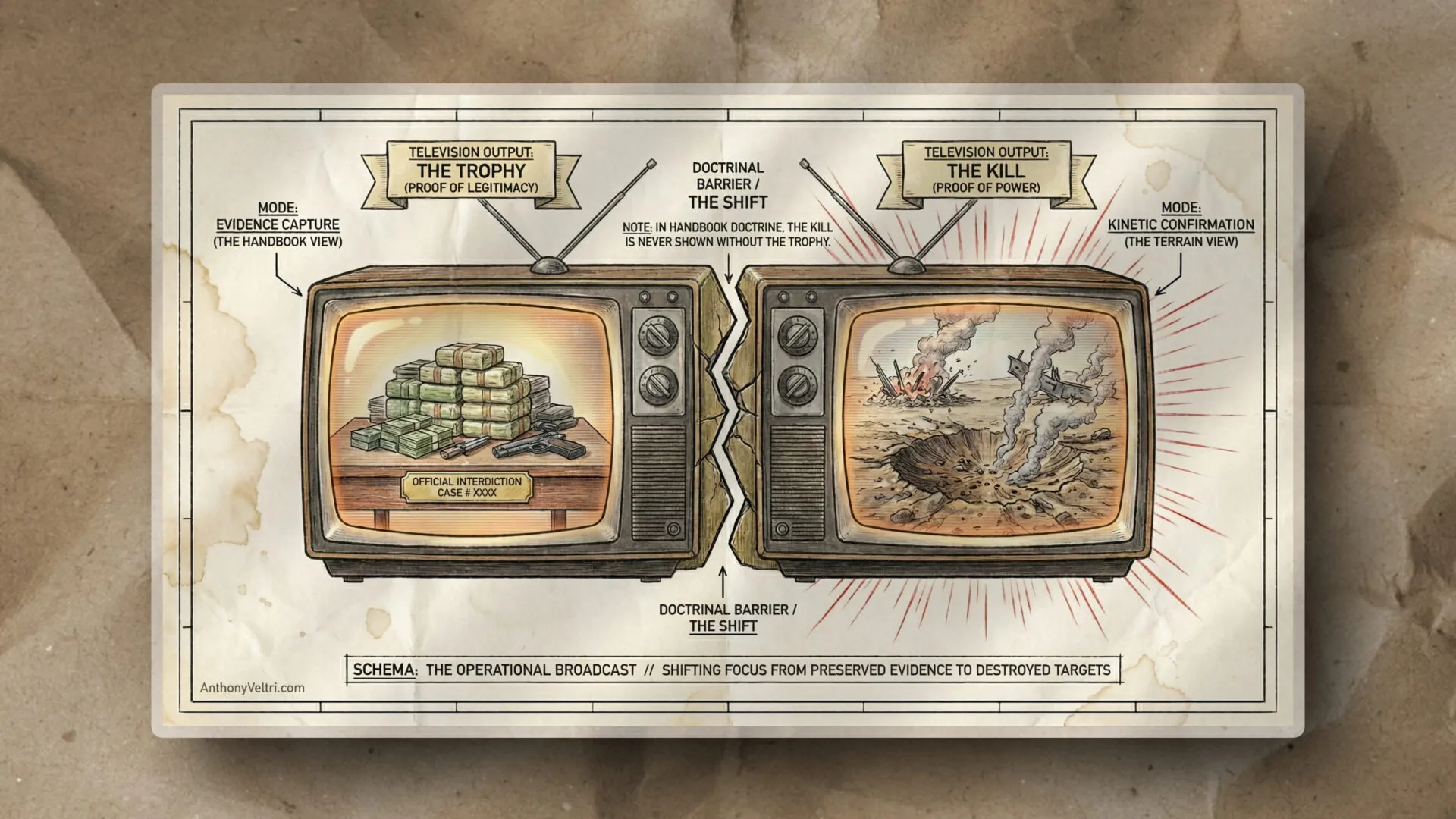

They have been in those coordination meetings: weekly pre-briefs to prepare for the next level of briefing, hours spent copying and pasting from SharePoint into new documents so content can be reviewed before the next coordination call. Sometimes this goes two or three layers deep before an executive actually sees the information.

Not only does this consume tremendous time, but every interface of copy-paste introduces opportunity for error and loses provenance. An individual office with someone skilled in SharePoint and Power BI may have built automation, but all of that automation collapses at the point of interface with another system using default configurations.

The secretary may want the manual process review because there have been so many telephone-game stages with copy-pasting by the time information reaches them. But Compass-X would still allow for that manual review before presentation to the secretary, with complete provenance of where information is coming from and automated pass-through before that.

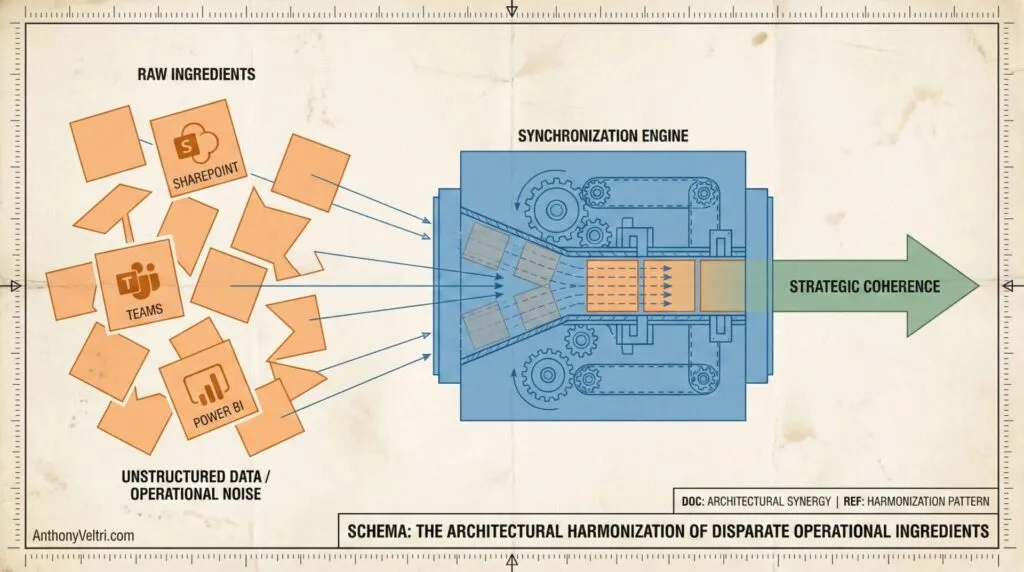

Why the gap exists: The Architecture of Intent

Microsoft provides the ingredient layer (Power BI, SharePoint, Teams). They intentionally offer high flexibility so that diverse organizations can define their own strategic priorities. What organizations require is the Recipe Layer: opinionated architecture that understands federal operational patterns and synthesizes visibility without forcing process conformity.

Microsoft builds infrastructure: they provide ingredients. What they specifically do not do is prescribe what matters strategically, because that differs across organizations. NASA has different priorities than USDA: USDA has different priorities than a construction firm.

Microsoft’s business model depends on flexibility. If they built opinionated portfolio architecture, they would have to choose which strategic patterns to support. Do they optimize for federal hierarchy? For construction project workflows? For research institution collaboration? Each choice would reduce flexibility for other customers. Their strategic decision is to provide infrastructure and let organizations build their own recipe layer.

Compass-X is the Recipe Layer built on Microsoft’s ingredient layer. It is repeatable architecture that knows federal operational patterns, understands federation constraints, and synthesizes strategic visibility without forcing process conformity.

What this tells you about organizational readiness:

When this question surfaces, the organization has felt the briefing prep pain. They know the current process wastes time and introduces error. They are ready for federation infrastructure if they can explain the decision internally.

If the conversation shifts immediately to implementation questions after understanding the gap (“Where does it go from here? What do you need from us?”), they are mentally at “how” not “if.”

For the foundational thinking on federation vs integration, see Doctrine 01: Federation vs Integration in Mission Networks.

Recognition Pattern 2: “We Could Just Build This Ourselves”

The question:

“Our team knows Power BI and SharePoint. We could probably build something like this ourselves.”

What this question reveals:

This is not about job security. The person asking is protecting what they have built, evaluating the architecture required to synchronize existing Microsoft components into a mission-specific visibility layer. They are expressing healthy skepticism about solving problems Microsoft chose not to solve, and they are right to analyze whether this specific integration of the “Stable Lane” will achieve the desired adoption. Will this get used, or will it become shelfware?

They are right to be skeptical. They are right to protect their work. And they are right that their team could build the technical infrastructure.

The Brass Plaque Principle: When Organizations Should Build It Themselves

I took a tour of Hoover Dam several years ago. Each generator is stories-high and has a brass plaque bolted to it identifying who maintains it: “Proudly Maintained by Mike E.” These generators and alternators are 70+ years old. They are not fungible. The maintenance cannot be replaced by contractor labor. This is mission-critical infrastructure that warrants permanent dedicated capacity with a name on it.

M365 skills, by contrast, are more fungible. Power BI developers are available. The question is not technical capability: the question is a strategic choice. Is portfolio visibility infrastructure mission-critical enough to dedicate permanent bench strength (the Hoover Dam case), or is your capacity better focused on mission-specific work?

If an organization has a dedicated M365 shop with bench strength to staff portfolio infrastructure in perpetuity, they should build it themselves. That is the Hoover Dam case: permanent capacity for mission-critical infrastructure.

But if that bench strength does not exist, the failure mode is predictable:

A capable Strike Team builds the infrastructure. It works technically. They return to their regular jobs. Six months later, when an executive wants a new view or a Microsoft update breaks integration, there is no one with context to fix it. The dashboard becomes shelfware: Shadow IT returns.

Choosing not to build in-house is often an act of Stewardship for the team’s limited capacity. I’m not advocating for a specific tool: I’m advocating for the protection of an organization’s “Strike Team.”

The adoption gap:

Organizations that build technical infrastructure themselves can reconstruct the dashboard patterns. What takes 18 months to discover are the adoption patterns that make federated portfolio visibility easier to use than manual briefing prep.

JPL spent years learning how to make executives trust federated data enough to stop demanding manual verification. How to surface portfolio-level risks in ways that prompt action rather than just acknowledgment. How to balance detail for those who need it with strategic summary for those who do not.

That is not technical work: that is behavioral design informed by pattern recognition across multiple deployments.

Technical reconstruction delivers the infrastructure. It does not deliver the adoption patterns. Without adoption, the infrastructure becomes unused.

What this tells you about organizational readiness:

When someone asks this question, they have capability to execute. The diagnostic question is about permanent capacity: Do they have bench strength for ongoing O&M, or would this consume Strike Team capacity that should stay focused elsewhere?

If they push back after understanding the brass plaque principle, they are either:

- The large organization with legitimate permanent M365 capacity (they should build it)

- Underestimating the O&M burden (stress test: who owns it six months from now?)

- Testing whether you respect their capability (partnership vs replacement)

Recognition Pattern 3: “Isn’t This Just Another Dashboard Tool?”

The question:

“So this is basically Power BI dashboards?” or “We already have dashboards, they just need better data.”

What this question reveals:

When people hear “dashboard,” they picture brittle systems that cannot evolve without heroic effort. Both scenarios reveal an Interface Conflict: systems that lack a parallel innovation lane. The skepticism is not toward the software, but toward the lack of a Synergistic Model that allows the visibility layer to evolve at the speed of the mission.

Specifically, they picture one of two scenarios:

- A Power BI report built “other duties as assigned” that drifted out of utility six months after deployment because there was no funding or prioritization to update it

- A ServiceNow instance with expensive licensing where contract modifications are required just to change a view

Both scenarios share the same constraint: something brittle that cannot evolve without heroic effort or budget approval.

This question reveals the organization has been burned by dashboard promises before. They have seen tools that worked initially but could not adapt. They have learned to be skeptical.

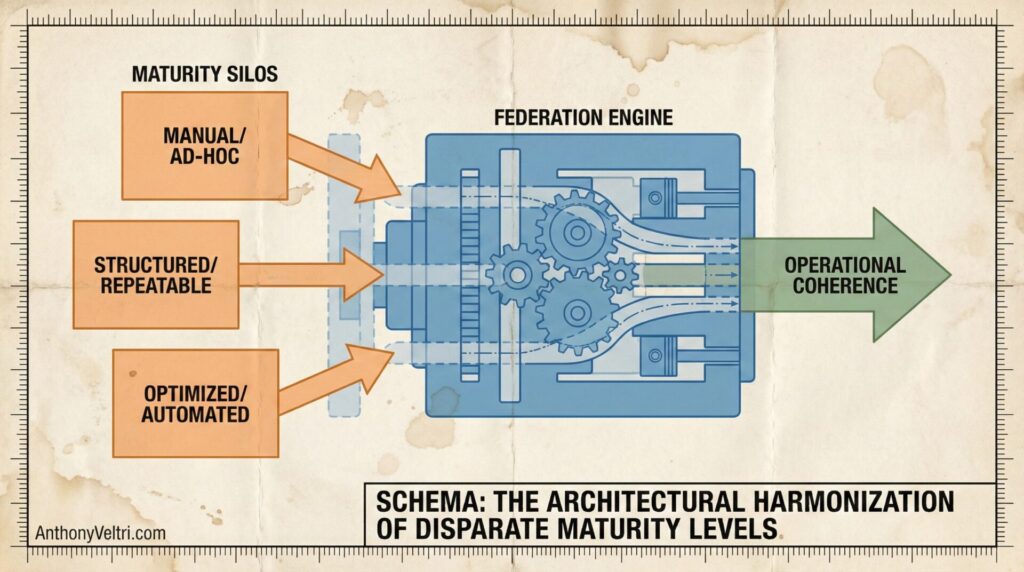

The Distinction Between Dashboards and Federation Architecture:

Dashboards are reporting layers: Compass-X is federated architecture.

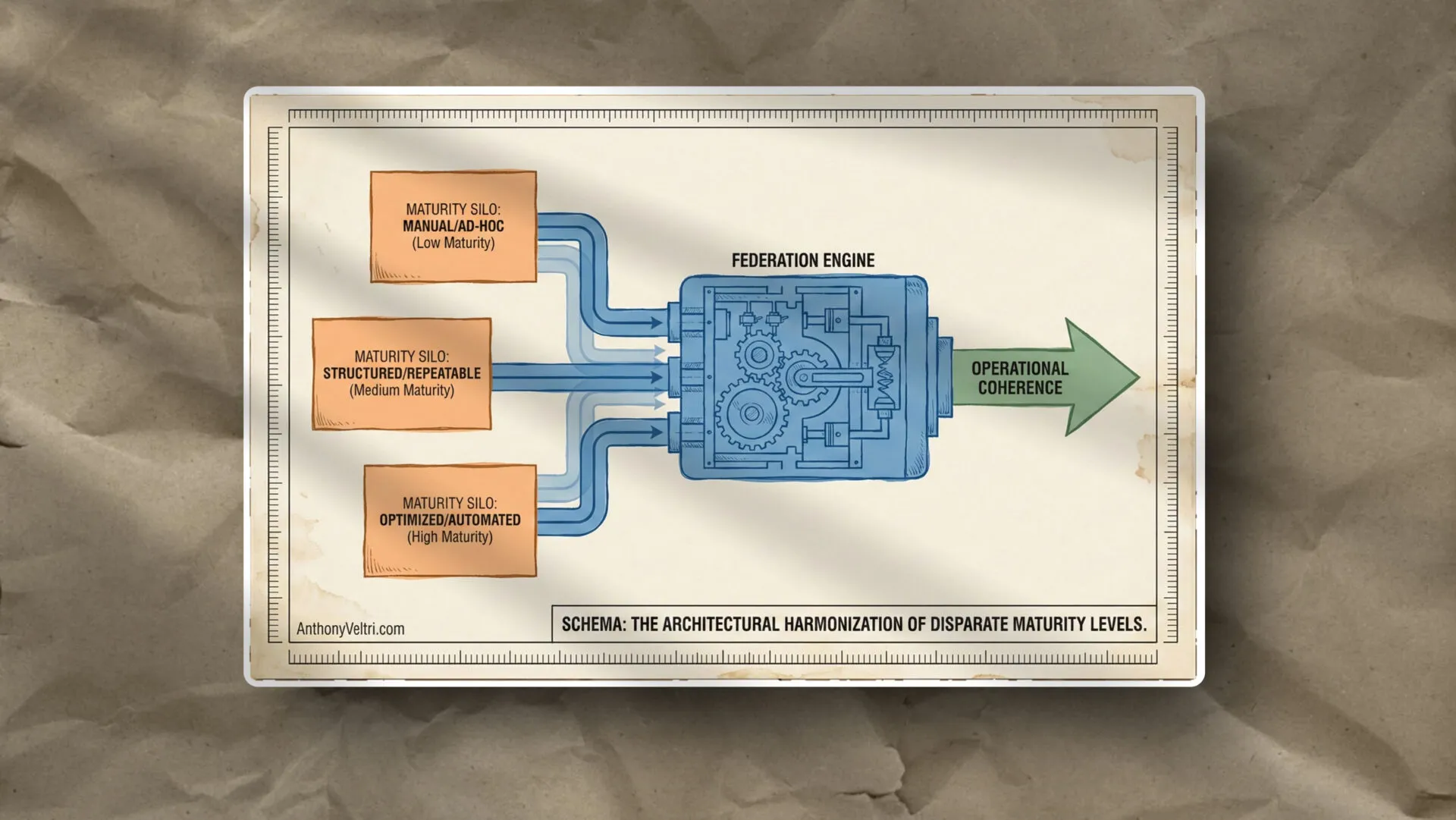

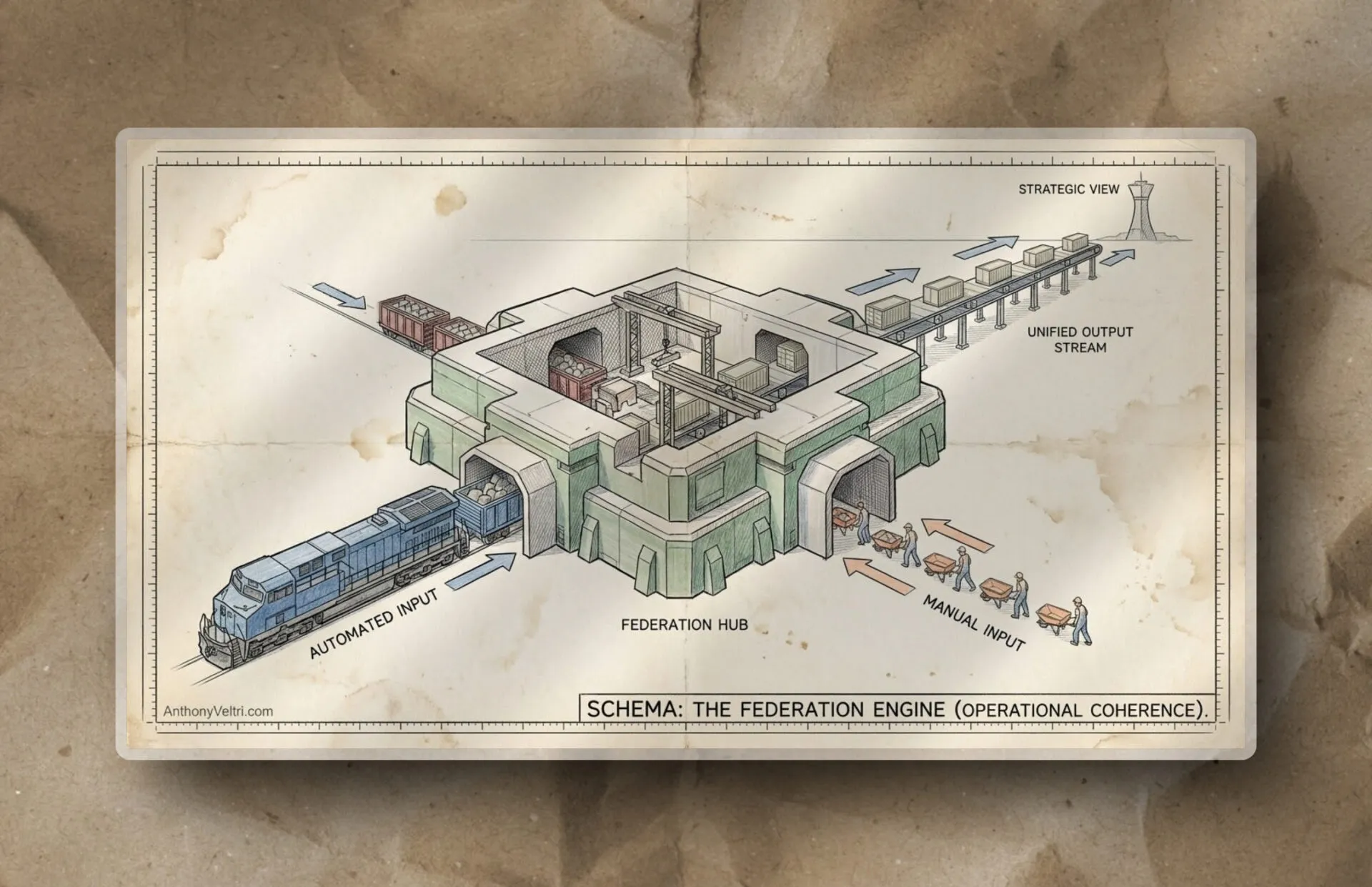

The distinction matters. Dashboards aggregate data from systems and display it. Federation architecture synchronizes data across autonomous systems operating at different maturity levels, maintains complete provenance, and enables strategic visibility without forcing process conformity.

Compass-X rolls up data from wherever the organization already works, regardless of project management maturity level, with complete provenance and no copy-paste interfaces. It does not require a new FedRAMP certification because it operates on the existing M365 tenant.

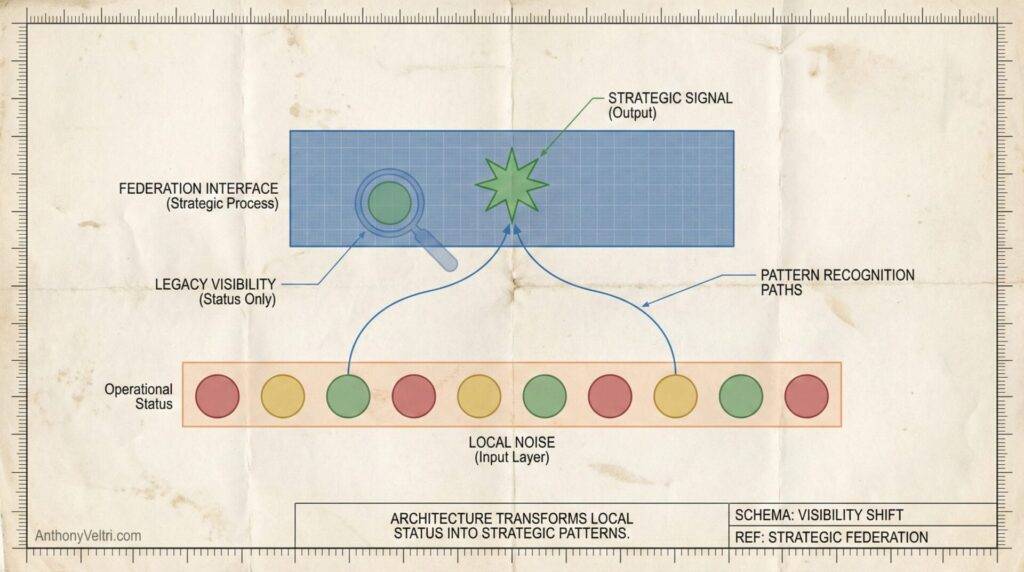

The shift from operational to strategic visibility:

Portfolio-level visibility reveals patterns invisible at the project level. One project might eliminate five other projects, but you cannot see that pattern looking at individual project status. Risks that appear isolated at the project level turn out to be systemic at the portfolio level.

This is the shift from operational visibility (What is the status?) to strategic visibility (What actually matters?).

The two-lane architecture frame:

Federal organizations typically have a stable lane for Microsoft-approved updates but no innovation lane for strategic experimentation. Dev/test/prod addresses operational stability. What is missing: a parallel lane where you can experiment with portfolio views, test OKR alignment approaches, try risk pattern identification without disrupting the stable lane where projects execute.

Compass-X provides that innovation lane. Because it operates on the existing tenant, strategic experimentation carries no risk to operational systems.

Most federal dashboards fail because they force everyone into stable lane conformity. Compass-X welcomes all maturity levels and synthesizes strategic visibility at the federation layer.

The proof point:

When you demonstrate data rolling up from multiple disparate sources (different SharePoint sites, different project management tools, different maturity levels) into unified portfolio view with complete provenance and history, not aggregated, not copy-pasted, but federated with lineage intact, people realize this is the synchronization layer they have never had.

What this tells you about organizational readiness:

If people remain skeptical after understanding the architecture distinction, they either:

- Have not felt the briefing prep pain personally (they delegate this problem)

- Think their dashboard problem is data quality (technical fix) not architecture (strategic fix)

- Do not have portfolio-level decision authority (strategic visibility does not matter to their role)

All three are valid. Not every organization needs federated portfolio infrastructure. Not every role requires strategic visibility. The question itself is diagnostic.

Here Be Dragons (a deep dive for those who dare)

The Licensing Question

When this surfaces:

The licensing question appears early in conversations because procurement complexity is a real constraint. Organizations need to know if this requires navigating the M365 licensing labyrinth before investing cognitive load in understanding the architecture.

The question is diagnostic. It reveals whether the organization has been burned by licensing surprises before.

Why it matters:

Compass-X is designed to operate on the federal baseline for M365. Some agencies have invested in additional individual licenses, others have not. This affects deployment scope but not fundamental architecture.

The key differentiator: Compass-X optimizes existing M365 investment rather than requiring new vendor relationships or FedRAMP certifications. Total deployment cost (one-time fee plus any additional licensing required) typically runs less than 10% of existing M365 spend.

This reframes the decision: not “new budget line for new vendor” but “optimization investment for existing infrastructure.”

What this tells you:

If licensing questions dominate early conversation before architecture understanding, the organization may have procurement trauma from previous vendor relationships. That is valid context to understand.

If licensing questions surface after architecture understanding, the organization is doing due diligence. That is healthy evaluation.

The Tightrope: Technical Depth vs Strategic Framing

The constraint:

Technical people need architectural substance. Strategic people need outcome clarity.

Both needs are valid. The failure mode is choosing one audience at the expense of the other.

The balance:

The pattern that works: establish the strategic frame first (innovation lane, pattern library, federation architecture). When technical people engage, the brass plaque principle works because it validates their capability while framing the strategic choice.

The conversation itself reveals what matters more to that specific audience: architectural substance or strategic outcomes. Both needs are legitimate evaluation criteria.

The Real Blocker: Executive Culture

The technology is never the constraint.

Compass-X works with almost any maturity level. If an organization has existing M365 investment and the pain points described above, the infrastructure can support them.

The real blocker: Does leadership foster adoption of new capabilities, or stifle them?

Even Gmail required behavioral change. Tools are only as effective as the behavioral change they enable and the culture that supports that change.

If an organization says “we want portfolio visibility” but continues demanding manual briefs with no trust in the data layer, Compass-X cannot solve that: that is a leadership problem, not an architecture problem.

The diagnostic:

If executives want portfolio visibility but refuse to trust any automated system, they are not ready for federated infrastructure. They need to address the trust gap first.

If executives want portfolio visibility and are willing to verify automated systems while building trust, they are ready. The verification period is expected. Trust is earned through demonstrated accuracy over time.

Connection to Broader Doctrine

Federation vs Integration (Doctrine 01):

Compass-X solves coordination problems through federation, not integration. It does not force every office to conform to one project management standard: it welcomes autonomy and synchronizes at the strategic layer.

Integration thinking (centralize, standardize, control inputs) fails when applied to coordination problems across autonomous entities. Federation thinking (distribute, verify outcomes, govern at service layer) succeeds.

Two-Lane Architecture (Doctrine 06):

The innovation lane concept is not unique to Compass-X. It is a general principle: systems need a stable lane for execution and an evolution lane for experimentation.

Dev/test/prod addresses the stable lane. Innovation infrastructure provides the evolution lane for strategic experimentation without disrupting operations.

Decision Drag (Doctrine 09):

Three layers of pre-brief meetings before executives get visibility is decision drag. It slows tempo. It introduces error. It wastes capacity.

Architecture is the remedy: federated synchronization that provides executives with portfolio view when needed, with provenance intact.

Reflection

I can talk about Compass-X with conviction not because I am selling something: but because I have sat in those pre-brief meetings. I have watched talented people waste hours manually aggregating data that should be automatically federated. I have felt the resignation of “This is just how it is.”

The recognition patterns matter because they reveal the hidden constraints of the organization. The Microsoft question reveals they have felt the pain and need language to explain the solution. The build-it-ourselves question reveals they have capability but need to evaluate capacity allocation. The dashboard question reveals they have been burned before and need to understand the architecture distinction.

These are not objections to overcome: they reveal the real problem (diagnostic signals) about whether an organization operates in terrain where federated portfolio infrastructure makes sense.

Not every organization needs Compass-X. But the ones that do already know the pain. The questions they ask reveal whether they are ready for this kind of infrastructure or whether other constraints need addressing first.

The problems Compass-X addresses are real. The infrastructure exists. The patterns are proven at JPL. Whether this specific implementation makes sense for a given organization depends on constraints, capacity, and culture.

The questions reveal which.

Last Updated on January 8, 2026