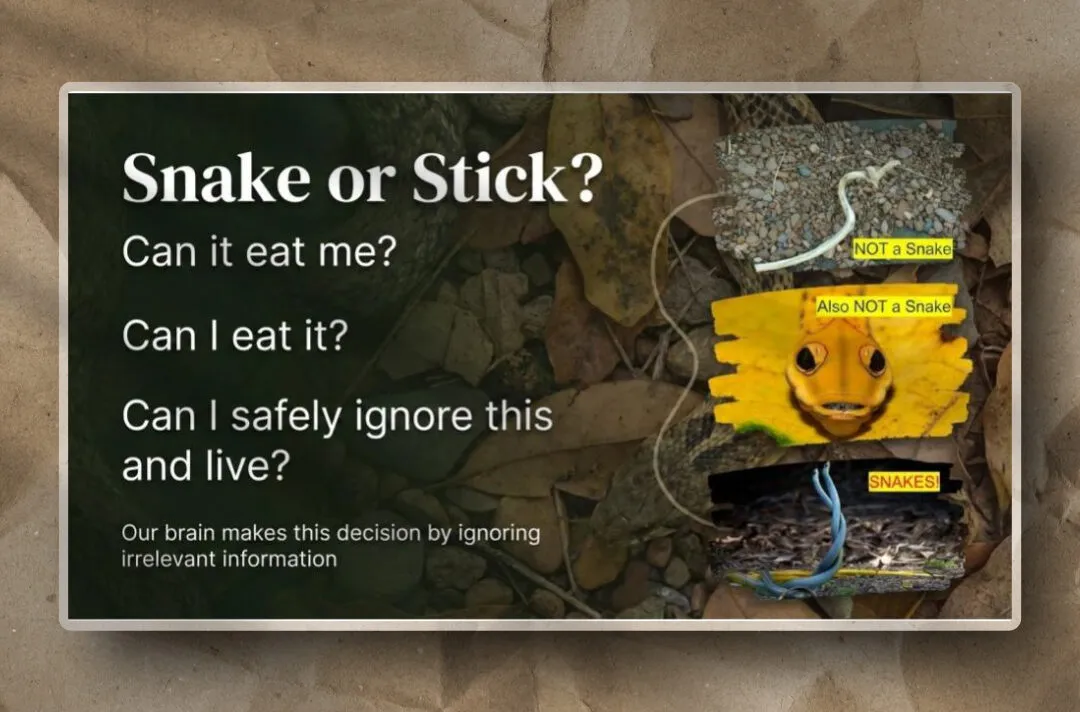

Field Note: Snake or Stick?!

Your brain is a cognitive miser.

It is constantly trying to answer one question fast:

“Can I safely ignore this and live?”

Because in the real world, you cannot afford to analyze every stick like it might be a snake. You also cannot afford to get the snake wrong.

So your brain runs a quick triage:

- Can it eat me?

- Can I eat it?

- Can I safely ignore this and live?

Most of the time, the answer is “stick,” and your brain discards the rest.

That is efficient for survival.

It is terrible for learning.

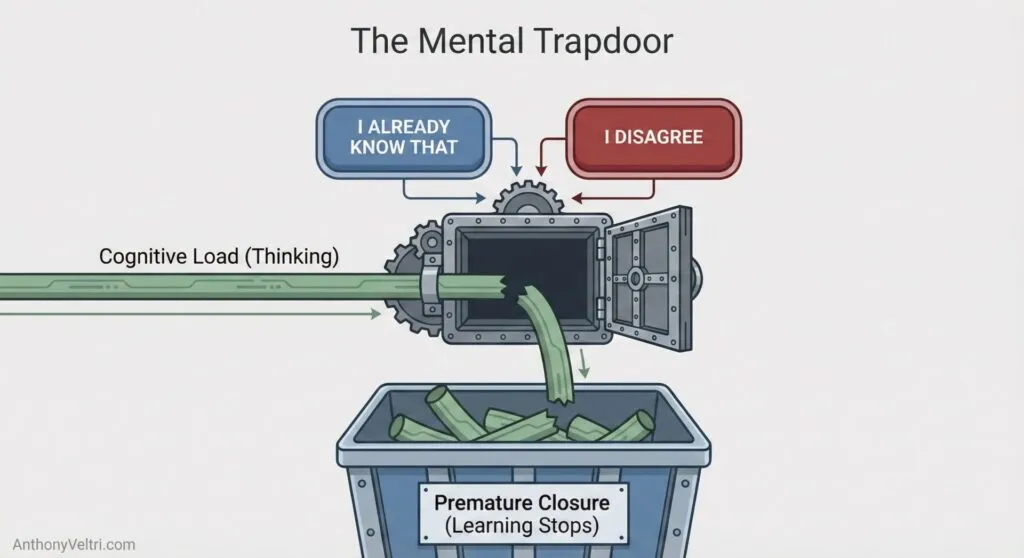

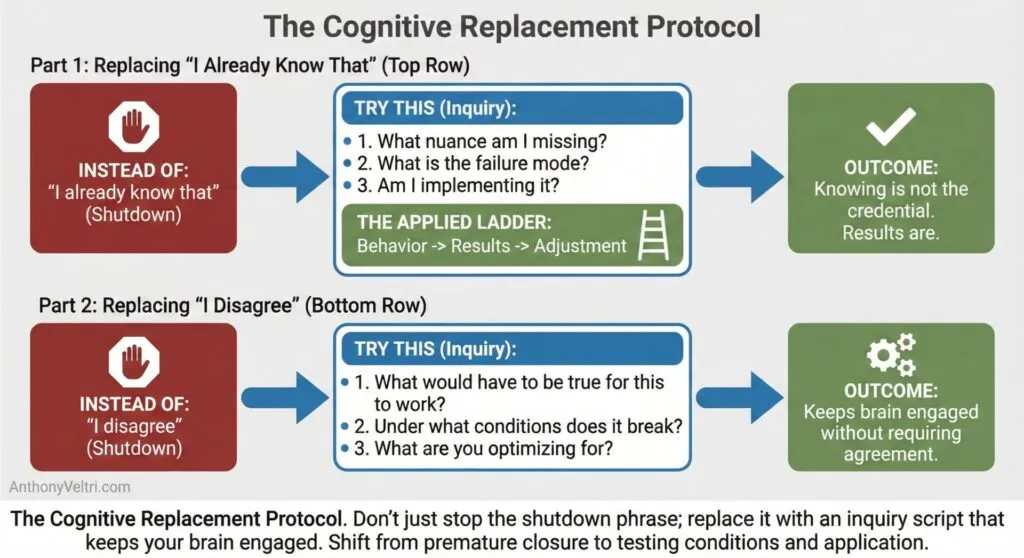

The two adult learning shutdown phrases

Two phrases act like a mental trapdoor. They end the cognitive load early:

- “I already know that.”

- “I disagree.”

Sometimes they are true. Often they are premature.

Either way, they trigger the same internal conclusion: “stick.”

And once the brain stamps “stick,” it stops holding the idea long enough to learn from it.

Why this is a learning problem, not a personality problem

“I already know that” and “I disagree” are not just opinions.

They are classification moves. They are your brain conserving energy by deciding the idea does not deserve further processing.

That mechanism keeps you from obsessing over every twig on the ground.

It also blocks you from noticing nuance, constraints, and the one detail that would have made the lesson actionable.

The move that fixes it

The fix is not “be more open-minded.”

The fix is: delay classification. (note this is for LEARNING MODE)

Hold the object in “snake mode” long enough to test it.

Not forever. Not philosophically. Just long enough to run a quick check.

Replace the shutdown phrases with these

Instead of “I already know that”

Start with:

- “I think I know this. What is the nuance I might be missing?”

- “What is different about your version?”

- “What is the failure mode if I assume I already know it?”

Then go deeper with the applied ladder:

- Am I implementing it?

Where does this show up in my actual behavior this week? - If I am implementing it, am I getting the results I should?

If not, one of these is true:

- I am doing a look-alike, not the real thing

- I am doing it inconsistently

- I am measuring the wrong outcome

- the idea has constraints I have not accounted for

A useful closer:

Ask: If I am implementing it, am I getting the results I should? If not, I don’t truly ‘know’ it yet. Knowing is not the credential. Results are.

Instead of “I disagree”

Use:

- “What would have to be true for this to be correct?”

- “What are the conditions where this works, and where it breaks?”

- “What are you optimizing for that I might not be optimizing for?”

These keep your brain engaged without requiring agreement.

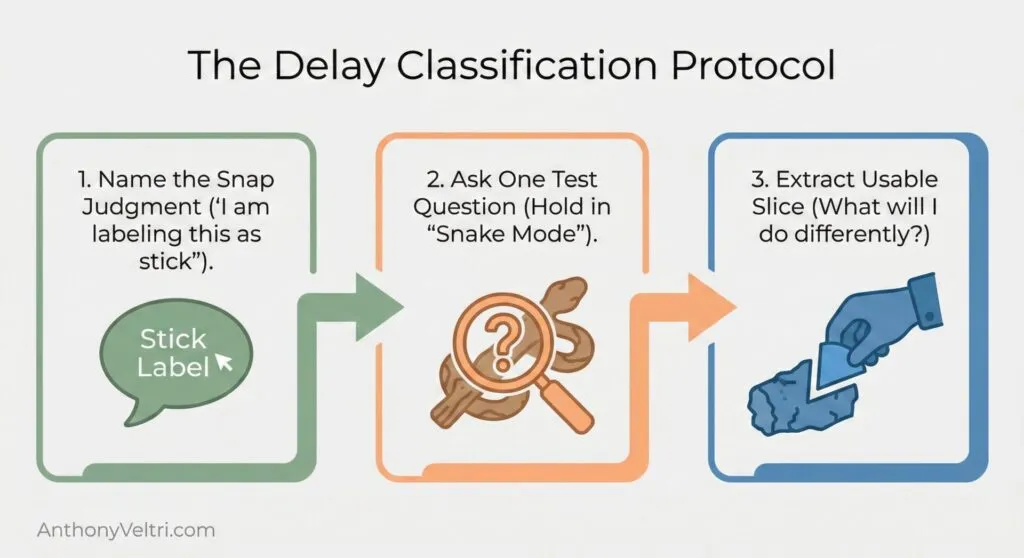

A straightforward protocol for learners and facilitators

Step 1: Name the snap judgment

“I feel myself labeling this as stick.”

Step 2: Ask one test question

- “What is the strongest example where this is true?”

or - “Where does this stop being true?”

Step 3: Extract the usable slice

“What is one thing I will do differently because of this?”

You do not need to adopt the whole idea to learn from it.

You just need to stop discarding it before it has a chance to teach you.

“Snake or stick is not about accuracy. It is about conserving attention. Learning requires delaying the ‘stick’ label long enough to test.”

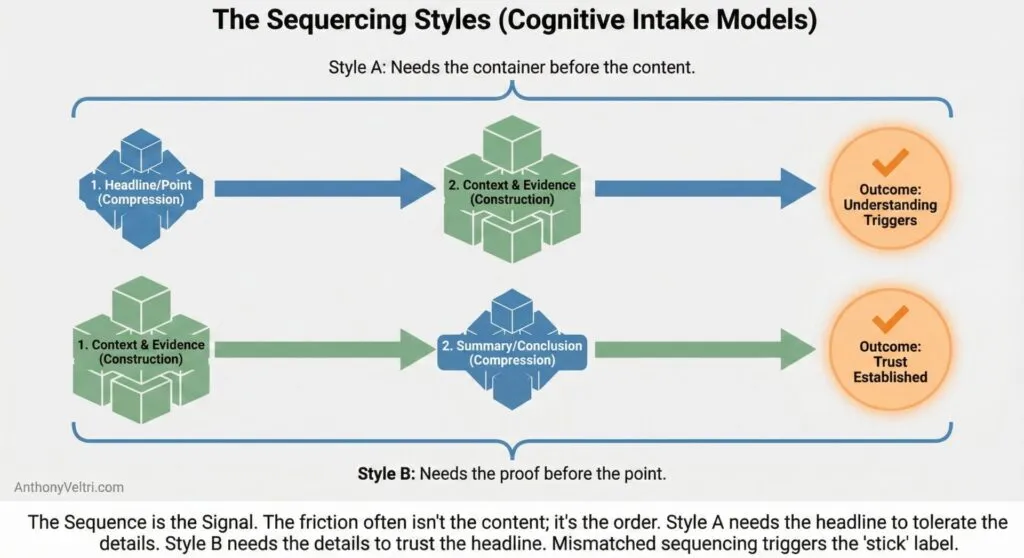

Add-on: Sequence is part of the signal

Sometimes the problem is not the idea. It is the order the idea arrives in.

Your brain is trying to decide “stick or snake” as quickly as possible, and sequencing affects that classification.

If the order feels wrong for the listener, they will unconsciously label the message as “stick” and shut down with:

- “I already know that.”

- “I disagree.”

- “Get to the point.”

- “That’s obvious.”

- silence, multitasking, or topic changes

Two common sequencing styles

Style A: Compression then Construction

This listener needs the headline first.

They need:

- the point up front

- the decision being asked for

- why it matters

Then they can tolerate detail because it has a place to land.

If you start with context and examples, they experience it as rambling or evasive, even if it is correct.

What they are really asking:

- “What are we doing here?”

- “What decision are we making?”

- “Why should I care?”

Style B: Construction then Compression

This listener needs the model first.

They need:

- context and constraints

- examples or evidence

- the mechanism

Only then does a summary feel trustworthy.

If you start with a compressed conclusion, they experience it as hand-waving or unsupported certainty, even if it is correct.

What they are really asking:

- “Based on what?”

- “What assumptions are you making?”

- “Walk me through how you got there.”

How sequencing triggers the shutdown phrases

If you give compression first to a construction-first person, their brain often jumps to:

- “I disagree” (because the conclusion arrived without its supports)

- “I already know that” (because the headline sounds generic without the mechanism)

If you give construction first to a compression-first person, their brain often jumps to:

- “I already know that” (because it cannot see the point yet)

- disengagement (because it feels like unnecessary detail)

In both cases, the listener is not rejecting the content. They are rejecting the cognitive load required to decode the content in that order.

The fix: select the order on purpose

You do not need to guess.

You can ask one question that prevents the “stick” label from firing too early:

“Do you want the headline first, or the walkthrough first?”

Or, if time is tight:

“I can give you the point in 15 seconds, then the reasoning, or I can walk you through the reasoning and end with the point. Which do you prefer?”

This small choice does two things:

- It respects the listener’s cognitive style.

- It keeps their brain from prematurely discarding the idea.

A practical two-track delivery pattern

Use this when you are speaking to a group or you do not know the preference.

Track 1: Compression first (15 to 20 seconds)

- “Here is the takeaway.”

- “Here is why it matters.”

- “Here is the tradeoff.”

- “Here is the recommendation.”

- “Want the walkthrough?”

Track 2: Construction first (45 to 90 seconds)

- “Here is the situation and constraints.”

- “Here are two key facts or examples.”

- “Here is the pattern or mechanism.”

- “So the takeaway is…”

- “Recommendation and tradeoff.”

The point for adult learning

Adults often believe the friction is disagreement.

Often the friction is sequencing.

If A strong learner and a strong teacher can do both directions:

- compress without losing truth

- construct without losing attention

- and switch when the room signals it needs the other order

That is how you keep the brain in “snake mode” long enough to test the idea, instead of discarding it as “stick.”

Note to self

When you feel the urge to say “I already know that” or “I disagree,” treat it like seeing a stick in tall grass.

Pause.

Hold it as a possible snake for 30 seconds.

Run one test question.

Then decide.

Last Updated on December 29, 2025