Field Note: Sorting the 20-Year Backpack

Or: When your tools only work if you’re the one carrying them and using them

Scene

It’s December 2025. I’m looking at five CSV exports of my own site (representing five individual, but interlinked tables) trying to explain to an AI why the bidirectional relationships aren’t broken when the data says they are. The AI assessed the work at 6/10 with “critical architecture failure” until I explained that shortcodes render the connections the CSV can’t see.

A quick translation: In this context, a shortcode is essentially an invisible steward… it is a small piece of code that acts as a contract between two pages, ensuring that if I mention a principle in a story, the story is automatically displayed alongside that principle throughout the site.

This is what happens when you build documentation infrastructure while you’re still figuring out what needs documenting. If this site fails as an interface, twenty years of high-stakes coordination thinking stays locked in private memory. This isn’t just about a website… it’s about whether a career’s worth of patterns can be transferred to the next person before the ‘bus’ arrives.

The last time I wrote about this site’s structure was that Sphere and Spikes piece. Back then, I was explaining why someone who isn’t a specialist can still build specialist things when they need them. The site was the example.

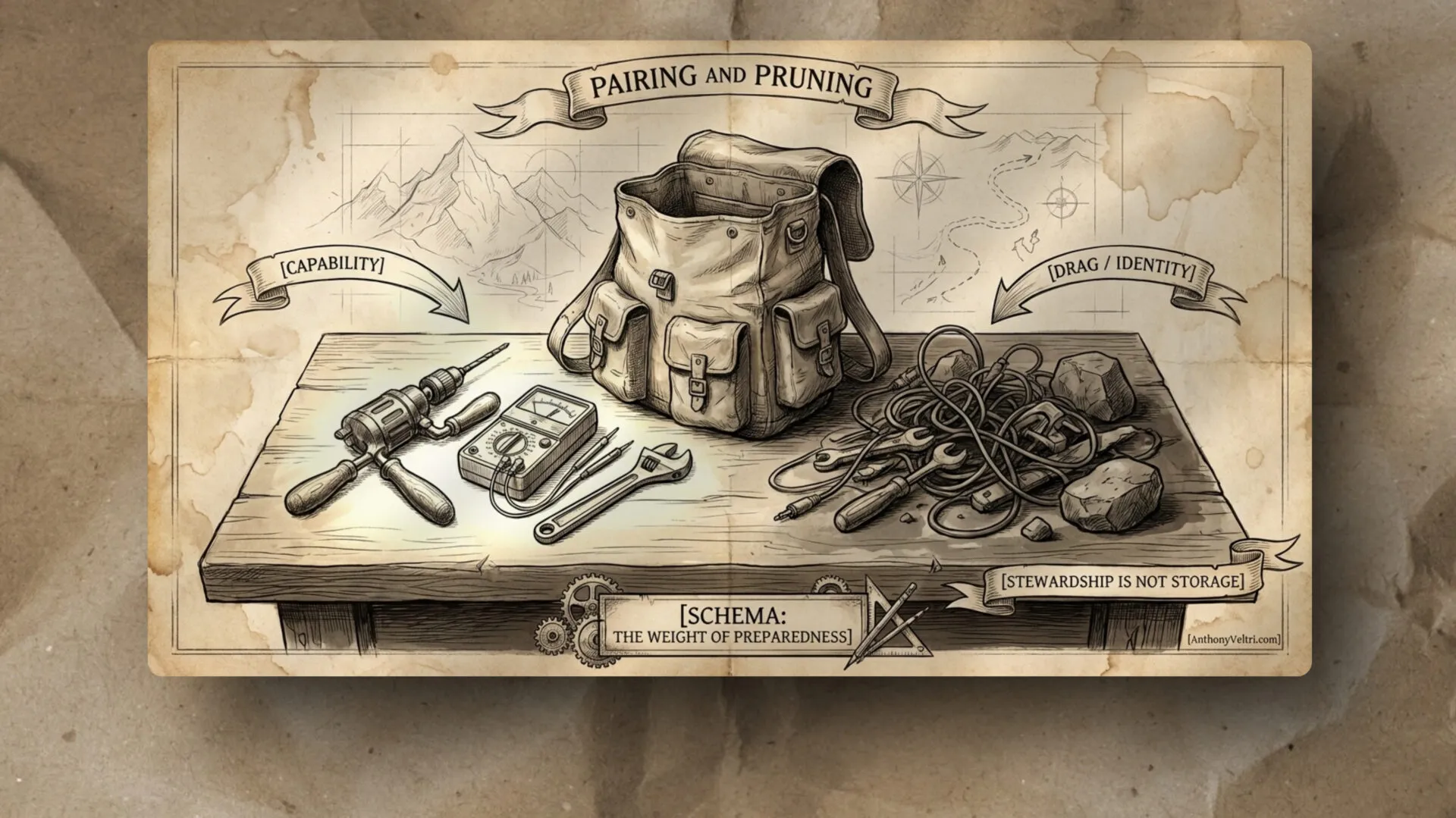

A lot has changed since then. Most of it because I kept running into the same realization: if the tools in your backpack only work when you’re the one carrying it, that’s not stewardship, that’s hoarding.

The 20-Year Backpack Problem

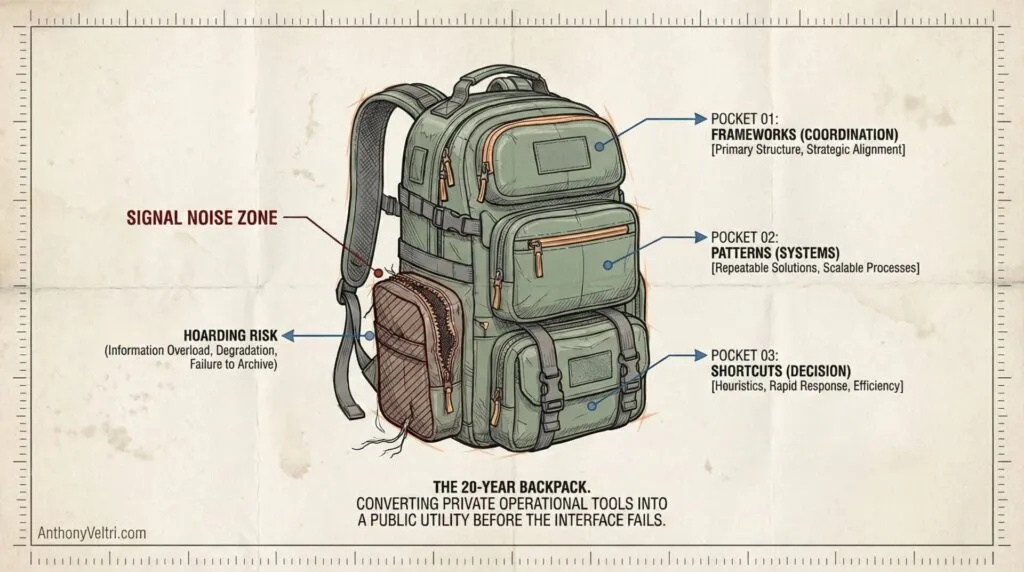

Twenty years of federal operational work generates a lot of tools:

- Frameworks for coordination across organizations that won’t coordinate

- Patterns for building systems when you can’t control the inputs

- Approaches to expert elicitation when experts can’t articulate what they know

- Decision-making shortcuts developed under pressure that actually work

The problem: These tools live in my head. Or scattered across old presentations. Or buried in email archives. Or referenced in conversations that ended years ago.

Usable by: Me. Maybe someone who worked with me directly. Nobody else.

That’s not stewardship. That’s a 20-year backpack where only I know which pocket holds what, and half the zippers are broken.

Why this audit matters now: This isn’t just a technical exercise in WordPress maintenance. As I sort through twenty years of federal operational work, I have realized that if this site fails as an interface, the patterns I’ve developed stay locked in a mental silo. This audit is the process of turning a “private backpack” into a “public utility” before the patterns are lost.

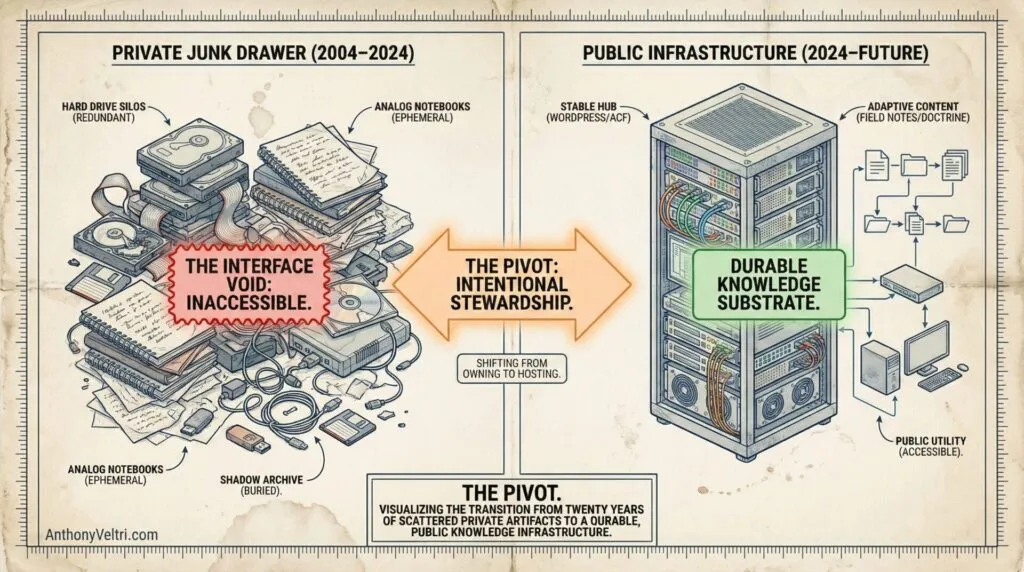

The Pre-Digital Silos (2004–2024) Before the first line of code was written for this site, the “Backpack” was literally a collection of disparate substrates: Hard Drives: Thousands of personal files across DHS, USFS, and personal drives, often with redundant versions.

- Analog Notebooks: “Decision Logs” from field operations that existed only on paper in my personal journals or audio dictations.

- Ephemeral Interactions: Patterns developed in high-pressure disaster responses that were never codified, only practiced.

- The “Shadow” Archive: Presentations and white papers buried in email archives that were forgotten long ago.

The Realization: I wasn’t just building a website; I was attempting a massive “Intake” and “Analysis” operation on twenty years of accumulated operational friction.

The Pivot: The website began as a desperate attempt to move from “owning” these patterns to “hosting” them; it was a shift from carrying twenty years of scattered artifacts in a private junk drawer to building a public infrastructure that could withstand a transition of ownership.

What This Website Started As (The Unorganized Backpack)

Structure: Chronological blog posts. Field notes were stories. Doctrine was principles. They lived in separate mental compartments.

Relationships: I’d mention concepts in stories. Sometimes I’d explain the principle. Mostly I assumed if you’d worked in this space, you’d recognize the pattern. If you hadn’t, you probably wouldn’t get it anyway.

Discovery: WordPress categories and tags. Which meant: good luck. You’d have to know what you were looking for to find it.

Philosophy: “Cover for action” – get the content published, worry about organization later. Which worked until someone asked “Where’s that thing you wrote about interface failures?” and I couldn’t find it either.

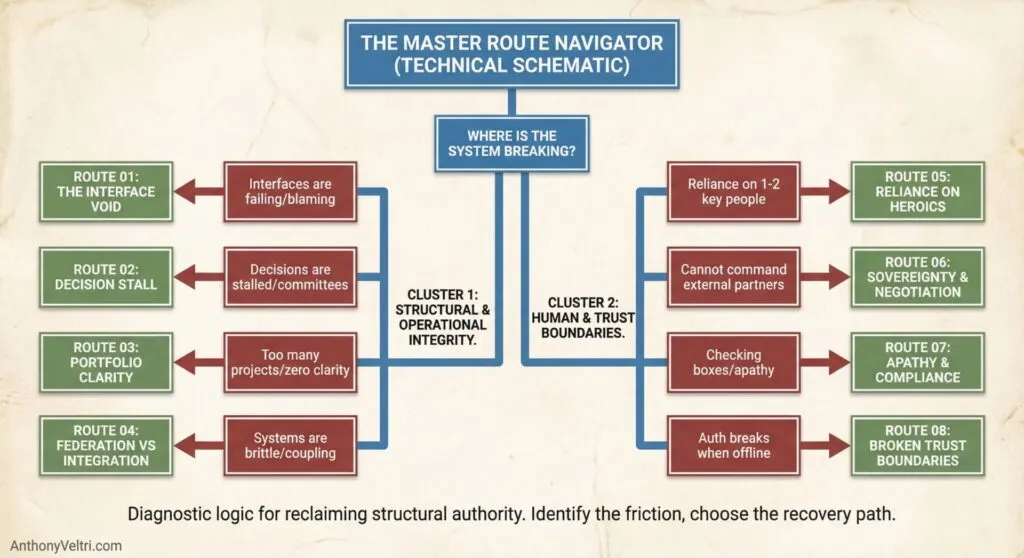

What Broke First: The Interface Problem

Doctrine 03 says interfaces are where systems break. Turns out the interface between documented knowledge and someone else’s ability to find it was breaking constantly.

The pattern: Someone would read a field note, find it interesting, then… nothing. No connection to the underlying principle. No path to related stories. Just: “Huh, interesting” and they’re gone.

I was creating the same problem I’d seen in expert interviews. The expert (me) had connected the story to the framework in their head. The reader saw a story without context. Interface void strikes again.

What I should have done: Follow Doctrine 03 and acknowledge that interfaces require stewards, contracts, and explicit connections.

What I actually did: Kept writing stories assuming people would figure out the connections themselves.

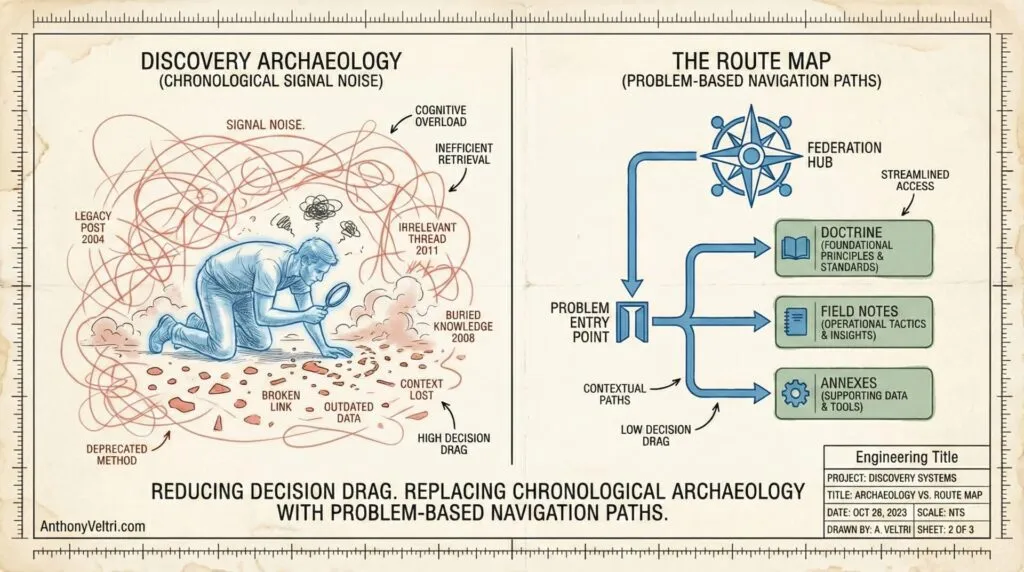

What Broke Second: Decision Drag for Discovery

Doctrine 09 says decision drag is the enemy of mission tempo. I was creating decision drag for anyone trying to find anything.

The pattern: Someone lands on the site looking for specific thinking. Maybe they’re facing interface coordination problems. Maybe they’re dealing with heroics propping up their system. But to find relevant content, they have to:

- Scroll through chronological blog posts (hope they guess right on date range)

- Search categories (hope I tagged it correctly years ago)

- Use site search (hope they use the same terminology I did)

- Give up and ask me directly (which defeats the point of documentation)

Time to useful content: 15-30 minutes if persistent. Most people aren’t.

I was asking people to do archaeology when they needed a map.

What Broke Third: Every Door Was Potentially Wrong

If you landed on a field note about interface failures, you couldn’t easily find:

- Other stories about interfaces failing in different contexts

- The principle explaining why interfaces fail structurally

- Practical guidance for “I’m facing this problem right now”

Every entry point was potentially a dead end. The backpack had tools, but good luck finding the right one.

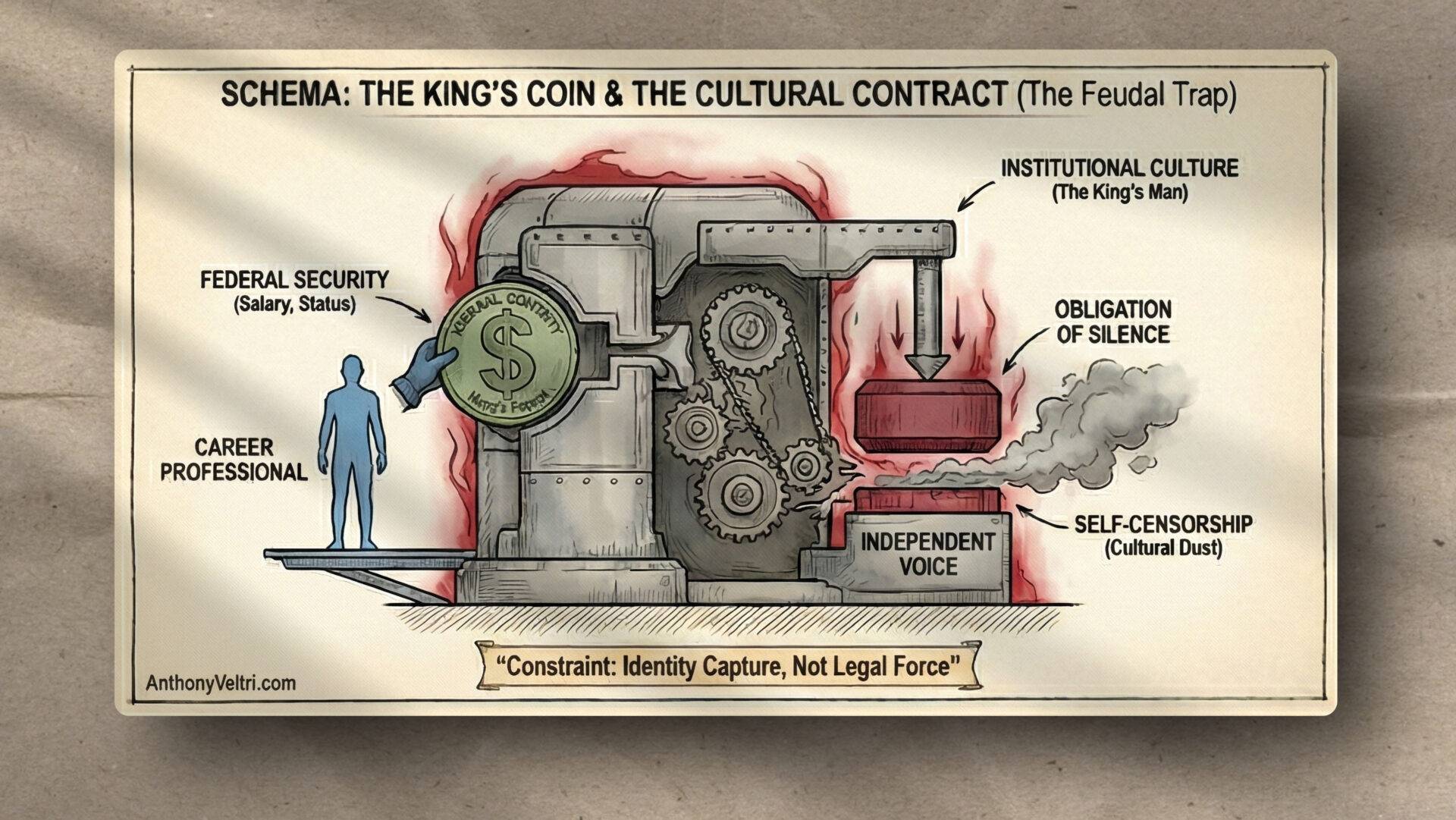

The Mirror in the Architecture I realized the site’s “dead end” problem was a digital ghost of an older, personal failure. By building a site that only made sense if you already thought like I did, I was repeating a mistake I made in 2012: assuming that being technically “correct” was the same as being “right” for the person on the other side of the interface.

Break: The 2012 Catalyst – Why I Started Thinking About Stakeholders

When Correct Isn’t Right

In 2012, a critical incident involving one of my employees showed me something I didn’t want to see. I knew how to follow procedures, but I didn’t know how to connect with people.

I handled the situation by the book; I did everything the agency’s critical stress incident protocols required. I followed the checklist, made the right notifications, coordinated the support services, and did the “correct” thing. But I didn’t do the right thing.

I wasn’t there as a person. I understood procedures, but I didn’t understand people. That failure (not procedural, but human) forced me to confront a reality I’d been avoiding: my communication “interface” only worked for people exactly like me.

The Reluctant Education (2012-2014)

At the insistence of colleagues, I started attending large group awareness training (LGAT) seminars and NLP workshops. I was extremely resistant… “cat-being-put-in-bathtub” resistant. This felt like pseudo-scientific consultant theater or a crystal shop in Taos with too much sage and incense.

Important caveat: I am not recommending LGAT or NLP training. I am not making a wholesale endorsement of these specific tools. They were very specific remedies for a very specific problem I had at that time. Just because they helped me get past a particular hurdle doesn’t mean they should be broadly recommended. Caveat Emptor, Your Mileage May Vary

What I extracted from that experience wasn’t the frameworks themselves (most of which are oversold). What I learned was the foundational principle that now governs this site: You can’t transfer knowledge effectively without understanding the receiver’s context, entry point, and mental model.

- You can suspend your ego long enough to understand someone else’s mental model

- Your way of processing information isn’t universal

- Meeting people where they are doesn’t mean abandoning rigor

- “Correct by the book” and “right for the human” aren’t always the same thing

Applying the Learning to Architecture

By 2014, I was applying this methodology to disaster coordination systems. I realized that federal partners, state coordinators, and field responders all needed different things from the same system. One interface could never work for everyone.

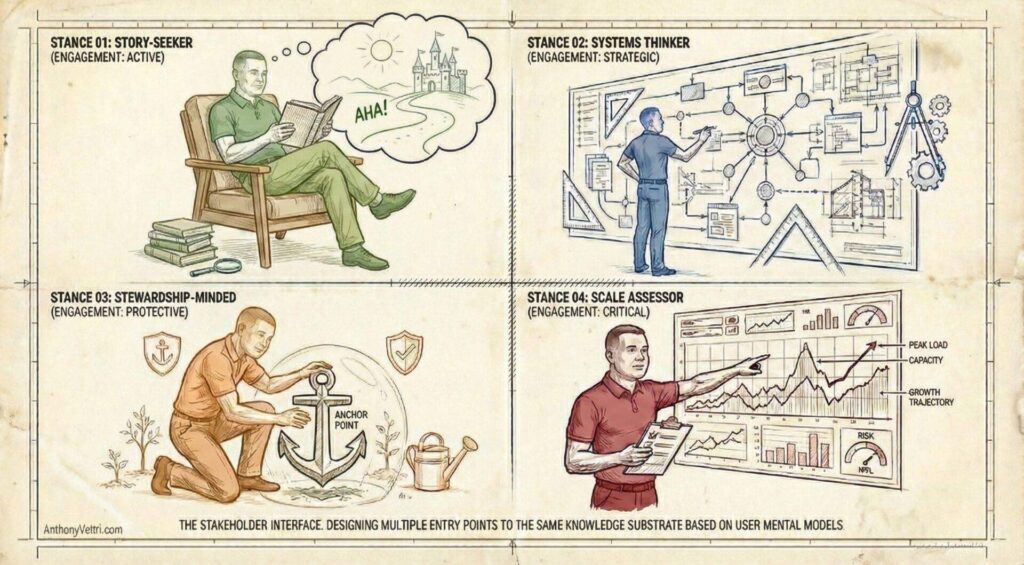

The 2012 failure taught me that a “one-size-fits-all” interface is actually a “one-size-fits-none” barrier. This insight drives the four stakeholder paths implemented in this current iteration:

- Story-Seekers (Narrative entry)

- Systems Thinkers (Structural entry)

- Stewardship-Minded (Verification entry)

- Scale Assessors (Outcome entry)

By building “Routes” and “Bidirectional Connections,” I am finally building the interface I lacked in 2012: one that meets people where they are and provides a bridge to where they need to go.

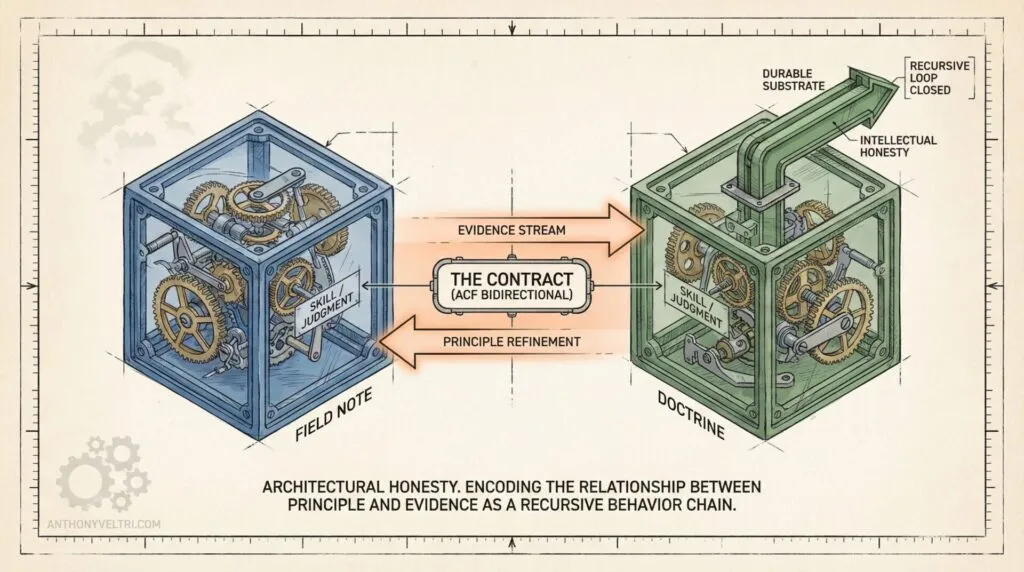

What Changed: Bidirectional Connections Through Architecture

The fix: Advanced Custom Fields with bidirectional relationships via shortcodes.

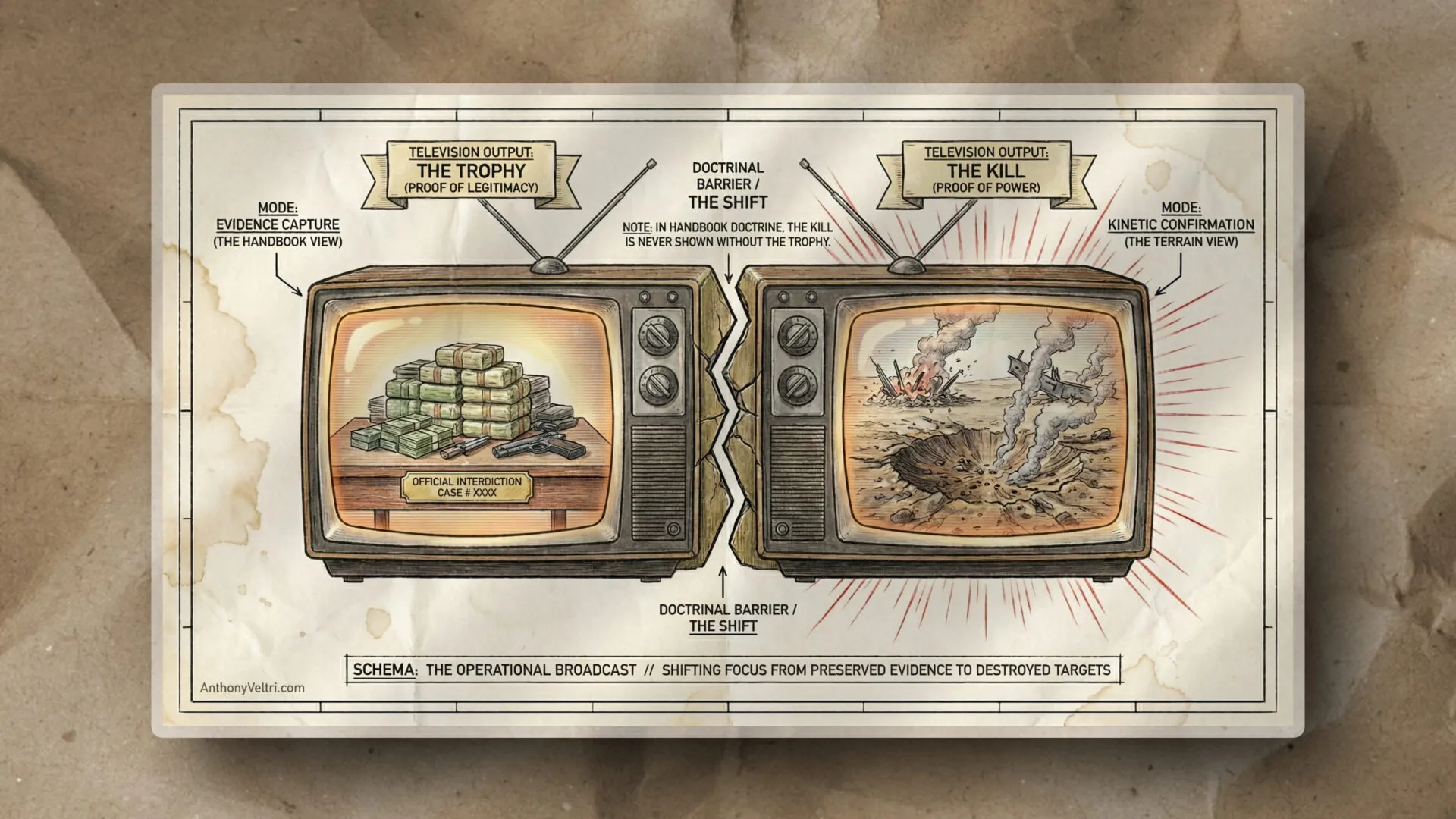

A mechanical schema of “Bidirectional Architecture.” The diagram illustrates how the relationship between a field note (evidence) and doctrine (pattern) is encoded via a “contract” (the ACF bidirectional shortcode). This process is designed to ensure intellectual honesty through recursive cross-referencing.

What this means: I set a relationship once in a field note (linking to doctrine principle). The shortcode renders it on both pages automatically. Field note shows related doctrine at bottom. Doctrine shows related field notes at bottom. Maintained in one place, displayed everywhere relevant.

Why this matters: It’s intellectual honesty through architecture. If I cite a principle from a story, that principle now has to acknowledge being cited. Can’t claim field-tested patterns without showing the field evidence.me

This is Doctrine 03 (interfaces require stewardship) applied to the site itself. The relationship is the interface. The ACF field is the contract. The shortcode is the steward.

Current state: Nearly all field notes have doctrine relationships working bidirectionally (we have a few stand-alone stories).

This isn’t about the technology. ACF and shortcodes are just the current implementation. The principle is platform-agnostic: if Content A references Content B, then Content B should acknowledge being referenced by Content A. You could implement this with database joins, graph databases, API endpoints, or whatever technology exists in five years. The principle is intellectual honesty encoded as architectural requirement.

What Changed: Routes for Problem-Based Entry

The realization: People don’t come to this site to browse my thinking. They come because they’re facing a specific problem right now.

The pattern I kept seeing: Someone forwards a field note about interface failures. Reader thinks “this is exactly my problem.” But then they can’t find the framework explaining WHY it’s happening or what pattern to apply.

The fix: 8 Routes pages serving as problem-based entry points:

- Route 01: When the interface is breaking (you’re becoming the patch)

- Route 02: If decisions stall and meetings go nowhere

- Route 03: If you have lots of projects but no portfolio clarity

- Route 04: If you’re confused about federation vs integration

- Route 05: If heroics are propping up your system

- Route 06: If you cannot force compliance across partners

- Route 07: If compliance exists but commitment doesn’t

- Route 08: If disconnected workflows create audit anxiety

Each Route: Problem statement → relevant doctrine → field note examples → next steps

Why this works: Matches how people actually arrive (with problems) rather than how I organized content (by type and date). This came directly from the 2012-2014 stakeholder analysis learning: meet people where they are (their problem), build bridge to where they need to be (understanding the pattern).

What Changed: Clinical Documentation for Systems Work

The problem: Field notes are operational narratives. Good for understanding thinking. Bad for assessing scope and outcomes of actual systems built.

The question people ask: “Okay, but did this thinking actually work at scale? Or is this theory?”

The fix: Doctrine Annexes providing clinical system documentation:

Annex K: System and Workflow Profiles (Case Studies). This serves as the “lookup table” for every real-world context behind the doctrine.

- Annex K: iCAV to GII/OneView. A system serving 296,000+ eligible users across all 22 DHS components and state & local partners via the HSIN network (evolved from 2008–2010 work). It provides a pure example of Two-Lane Architecture: the stable lane (OGC-compliant services) maintained zero downtime during national activations, while the adaptive lane (mission-specific sandboxes) allowed the field to experiment without breaking the core.

- Standards-Based Evolution. Annex K documents how a federation approach survived a total platform migration (from Internet Map Server to Portal for ArcGIS) because it was built on service-oriented architecture rather than centralized, monolithic integration.

- High Visibility Stress Tests. Detailed profiles of Federal Register Notices and Congressional inquiries illustrate how the doctrine protects operators from “leadership thrash” and “schema instability” during high-stakes political or legal review cycles.

- Self-Similar Patterns. The annex extends into personal domains: such as neuromotor recovery after mission-induced GBS and historic stewardship of an eighteenth-century farmhouse. These cases demonstrate that architectural patterns like “minimum viable function” and “preventive maintenance cycles” are universal across both technical and biological systems.

- Compass X and Modern Ecosystems. Profiles of federated decision support layers built on Microsoft 365 bring the doctrine into modern enterprise environments, illustrating the need for clear “data contracts” within cloud automation pathways.

Format: Scale metrics, organizational scope, technical decisions, outcomes, lessons learned. Clinical, not promotional. The systems speak for themselves.

Why this works: Preserves field note narrative while providing systematic operational history. Field notes link to annexes for comprehensive details.

This serves the Scale Assessors identified in stakeholder analysis – people who need to verify “prototype or production? one-time success or sustained capability?”

What Changed: Understanding the System Has Stakeholders

Initial thinking: Write operational stories. Document principles. Put them online.

Current understanding (from 2012-2014 learning): Different stakeholders need different things from the same knowledge base.

Four stakeholder types identified:

Knowledge management challenge: Same content base, different discovery paths and documentation formats needed.

Solutions implemented:

For Story-Seekers:

- Field notes maintain narrative voice

- Related field notes create narrative arcs (in progress)

- Operational texture preserved (no sanitization)

For Systems Thinkers:

- Bidirectional doctrine relationships (principle ↔ evidence)

- Doctrine cross-references for related concepts (in progress)

- Visual frameworks for complex patterns (diagrams integrated)

For Stewardship-Minded:

- Bidirectional relationships ensure intellectual honesty

- Revision tracking shows iteration

- Pretentious twit check filters consultant-speak

- Authentic voice with limitations acknowledged

For Scale Assessors:

- Clinical annexes with metrics and outcomes

- System evolution documentation

- Third-party validation where available (Esri article, etc.)

- Sustained results over time

The insight (from 2012-2014): You can’t just “organize content.” You need to understand who’s trying to use it and provide appropriate entry points and formats for each stakeholder type.

This is the multi-organizational coordination challenge applied to knowledge management: same knowledge base, different organizational needs and contexts.

What Changed: Acknowledging the Meta Problem

Here’s the thing about organizing a 20-year backpack: you’re doing it while still carrying it forward.

Started with “document operational stories.” That was right.

Realized stories need connection to principles. Added doctrine. That was right.

Realized principles need evidence they work. Added bidirectional relationships. That was right.

Realized people need problem-based entry. Added Routes. That was right.

Realized systems work needs clinical docs. Adding annexes. This is right.

But each fix revealed the next gap. It’s not “design the perfect backpack upfront.” It’s “organize what you have, discover what’s missing, iterate.”

The site’s current structure violates temporal arbitrage (doctrine about tech pace vs institutional pace). I keep reorganizing faster than people can catch up to the last structure. That’s probably suboptimal, but I don’t know how else to learn what’s needed.

What’s Still Broken: Outcome Documentation Sparse

The gap: Field notes tell operational stories. Doctrine explains principles. But scale indicators and sustained outcomes are scattered.

What’s missing:

- System metrics (users, organizations, operational duration)

- Evolution paths (what systems descended from this work)

- Sustained impact (what’s still running, what patterns continue)

Current approach: Brief outcome notes in field notes, comprehensive documentation in annexes. In progress, not complete.

Why this matters: Without outcomes, readers wonder: “Did this work or just sound good?”

What’s Still Being Figured Out: Narrative Connections

The opportunity: Related field notes that demonstrate pattern across contexts but don’t directly link to each other.

Example: “The Loudest Listener” (expert interview failure) and “Guided Sensemaking Interview” (RS-CAT application) both demonstrate expert elicitation challenges. They both link to doctrine, but not to each other directly.

The problem: Someone reading interface failure stories can’t easily discover other interface failure stories in different operational contexts.

Next iteration: Create narrative connections between related field notes, not just field notes → doctrine.

Break: Why This Actually Matters

If I get hit by a bus tomorrow, does the 20-year backpack help anyone?

Currently: Maybe. If they know what to look for and can navigate the structure. If they stumble on the right field note. If they follow the relationships to doctrine. If they connect dots I connected in my head.

That’s not good enough.

Stewardship means: someone else could pick up this backpack, understand which tools are for what, and use them without me explaining. That’s the standard.

Are we there? No. But closer than before.

What’s working:

- Bidirectional relationships mean you can trace principles to evidence and back

- Routes mean you can start from your problem, not my taxonomy

- Annexes mean you can verify systems worked at scale, not just theory

- Voice is authentic (passing pretentious twit check, no consultant-speak)

What’s not:

- Outcome documentation incomplete (annexes in progress)

- Narrative connections missing (related stories don’t cross-link)

- Figure integration unknown (are diagrams properly connected to text?)

- Some tools still only I know about (haven’t surfaced yet)

Schema: What This Demonstrates About Documentation

Pattern observed: Documentation infrastructure should follow the principles it documents.

Doctrine 03 (Interfaces): Applied through bidirectional ACF relationships – the interface between content types has steward (shortcode), contract (ACF field), and explicit connections

Doctrine 09 (Decision Drag): Applied through Routes – reducing time from “I have this problem” to “here’s relevant thinking”

Doctrine 01 (Federation): Applied through distributed content types (posts, doctrine, annexes, Routes) with service-layer connections rather than monolithic structure

Doctrine 06 (Two-Lane): Applied through stable infrastructure (WordPress, ACF, bidirectional architecture) + adaptive content (ongoing field notes, evolving doctrine)

The recursive property: A site documenting coordination principles should itself be well-coordinated. If it’s not, question the principles.

The stakeholder principle (from 2012-2014 learning): A knowledge management system serving multiple organizational contexts needs multiple interfaces to the same knowledge base. Meet people where they are, build bridge to where they need to be.

Current state: Getting there. Not finished. Better than last iteration.

What This Cost

Time investment since Sphere and Spikes piece:

- 24-day documentation sprint (23 doctrine volumes, 12 annexes, 410+ diagrams)

- Ongoing refinement using RS-CAT framework (making tacit explicit)

- Multiple architecture iterations as gaps discovered

What I’m not counting: The operational work that generated the content. That’s the job. This is just making it sortable and findable.

Opportunity cost: Could be generating new content instead of organizing existing. But if nobody can find what exists, new content doesn’t help. Sometimes more is better. Sometimes better is better.

Worth it? Ask me when someone else successfully uses one of these tools.

What This Reveals About Stewardship Obligation

The Sphere and Spikes piece was about building capability without becoming a specialist. This piece is about maintaining that capability once it exists.

The obligation: If you develop tools through 20 years of operational work, and those tools actually work, you have a responsibility to make them accessible. Not for credit. Not for positioning. Because someone else will face the same problems and shouldn’t have to rediscover solutions that already exist.

Stewardship means:

- Regular audits (CSV export, external analysis to catch blind spots)

- Fixing broken architecture when discovered (ACF relationships)

- Adding missing infrastructure (Routes, annexes, narrative connections)

- Preserving what works (operational voice, intellectual honesty)

- Understanding stakeholders and meeting them where they are

It also means: Knowing when to stop optimizing and start using. This site could be better. It could also be never-finished permanent beta. At some point, organized enough is organized enough.

We’re not there yet. But the backpack is more sortable than it was.

What Changed in This Iteration

Architecture improvements:

- Bidirectional relationships: 57 of 60 field notes connected to doctrine

- Problem-based navigation: All 8 primary Routes are now operational and cross-linked.

- Clinical documentation: Annexes framework established, first annex in progress

- Stakeholder-appropriate interfaces: Multiple content types and entry points for different needs

- Authentic voice maintained: No consultant-speak, (this is very challenging for me, but I am improving)

- Intellectual honesty: Clear about working vs broken, present, vs aspirational

What’s next:

- Complete outcome documentation (annexes for major systems and operations)

- Audit figure integration (parse HTML, identify orphans, add missing diagrams)

- Create narrative connections (field note → field note relationships for pattern recognition)

- Test usability (can someone unfamiliar navigate from problem to solution?)

The measure of success: Not “is this site perfect?” but “could someone else use these tools without me?”

Still working on it.

Related Field Notes

- Link to original “Why This Site Has Four Navigation Systems“

- Link to Sphere and Spikes piece

- [Link to upcoming “The Marketing Tools I Used to Think Were BS” – methodology deep dive]

Last Updated on January 31, 2026