Field Note: The 1790 Farmhouse and What It Taught Me About Stewardship

Field Note: We moved into a 230-year-old farmhouse. I’m still learning what that means. The house keeps teaching me things about systems, maintenance, and what it means to be responsible for infrastructure you didn’t build but are expected to pass forward. This is what I’ve learned so far about stewardship, mostly from making mistakes and finding tools I don’t know how to use yet.

It was built in 1790, before the Louisiana Purchase, before the Constitution was a decade old, before anyone knew whether this experiment in democracy would survive its first generation. The families who built it, lived in it, and passed it forward faced the Civil War, two world wars, the Spanish flu, the Great Depression, droughts, floods, and economic collapses that wiped out entire ways of life.

The house is still standing.

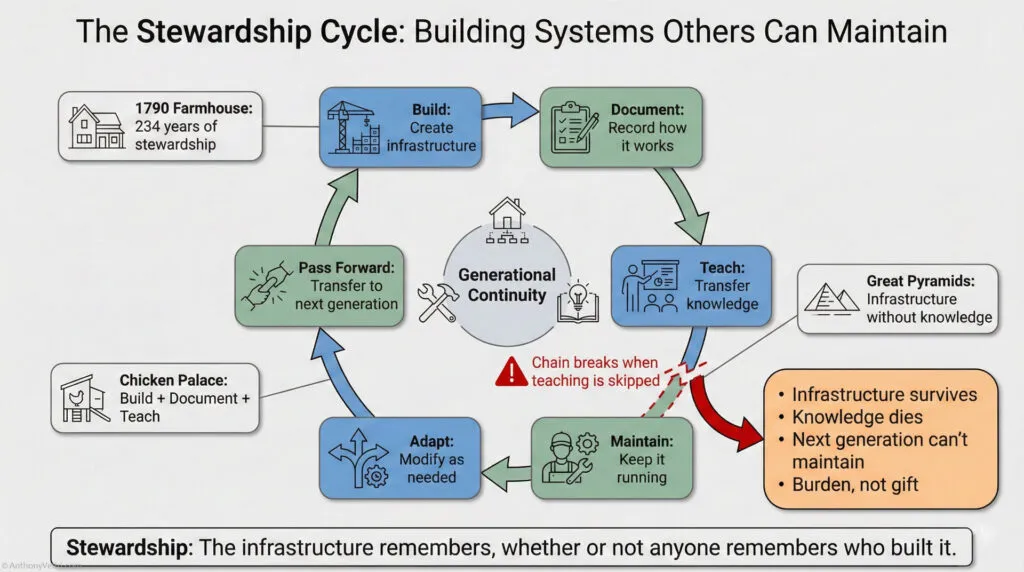

Not because it was built perfectly. Not because it never needed repair. But because generations of people chose to maintain it, adapt it, and pass it forward to the next steward.

We didn’t choose this house because we wanted to live in history. We chose it because it chose us. And we chose to answer with care.

What I didn’t expect was how much the house would teach me about systems, stewardship, and the difference between maintaining something and actually understanding what you’ve inherited.

The house began to reveal itself

Within weeks of moving in, we started finding things.

Tools tucked in rafters. Hand-forged implements in drawers. A scythe with a handle worn black from decades of use. A wood stove that predates the electric grid. Small relics hidden in corners, traces of the work that came before us.

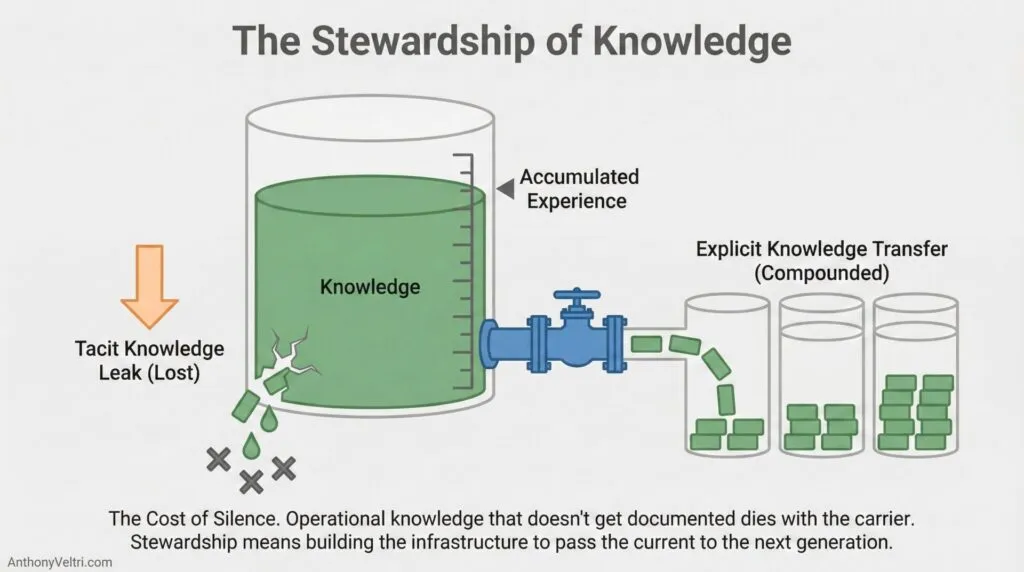

Each time we discovered something, I would research what it was for and how it was used. Often, there was little written about these objects. Much of it lived as tacit knowledge, passed hand to hand, shown rather than explained.

That became part of the responsibility too.

The people who used these tools didn’t think to document them because the knowledge was commonplace. Everyone knew how to sharpen a scythe, regulate a wood stove, or maintain a plumb wall. It was ambient knowledge, like knowing how to start a car or check your email today.

Then the generation that knew died. And the knowledge died with them.

Now we have museum pieces we can’t operate. Tools we inherit but can’t maintain. Systems built by people who assumed the next generation would just know.

This is the human condition, at least in today’s day and age.

We inherit infrastructure we can’t maintain. We receive tools without instructions. We’re given systems that worked for the builders but break when we touch them because no one documented the tacit knowledge required to keep them running.

The Great Pyramids were built with techniques so commonplace to their builders that no one thought to write them down. A few generations later, that knowledge was lost. Now we stand in front of monuments we can’t replicate and argue about whether aliens built them.

The pyramids are still there. The knowledge isn’t.

Bad stewardship doesn’t just fail to maintain infrastructure. It burdens the next generation with infrastructure they can’t maintain.

What the scythe and the stoves taught me

The scythe was the first teacher.

The handle is worn black where generations of hands applied force. But the handle doesn’t do the work. The edge does. You peen the edge into shape, then hone it with a fine stone, stroke by stroke. Upfront attention keeps it cutting. Grip strength doesn’t matter if the edge isn’t prepared.

The scythe teaches preparation over effort.

The stoves were the second teacher. But I should be more precise: the stoves, plural, were the teachers.

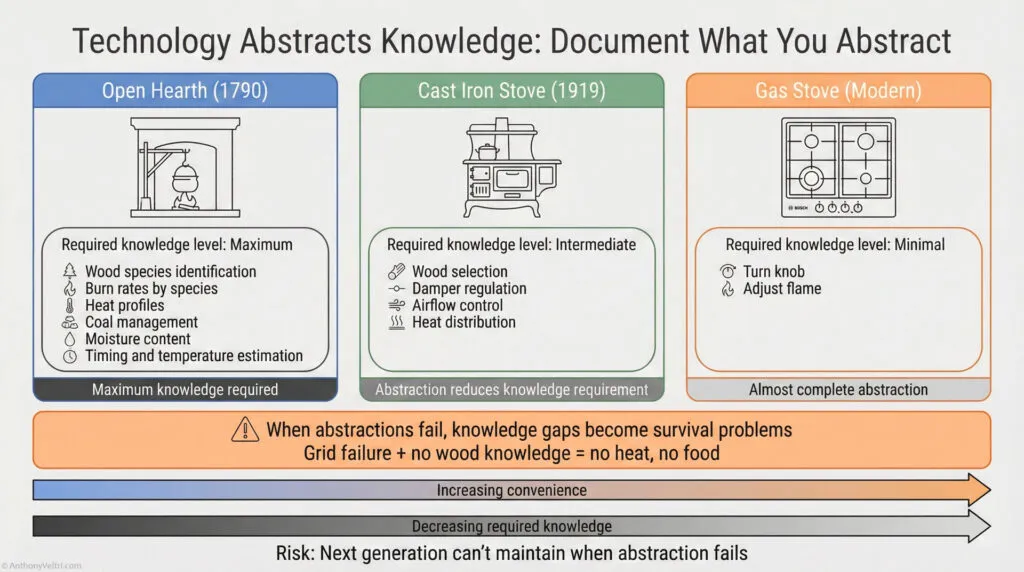

In our kitchen, I can stand in one spot and see three generations of cooking technology at once.

Behind me is the original hearth, an 8-foot open fireplace you can literally stand inside. There’s a crane for hanging pots over the fire. When we moved in, we found historical town records describing this hearth because it was so spectacular at the time. Cooking over an open hearth requires tremendous knowledge: different woods burn at different temperatures, produce different heat profiles, and leave different coals. You’re not just managing your food. You’re managing your fuel. Oak burns differently than ash. Hardwood versus softwood. Green versus seasoned. The fire is your tool, but only if you understand what you’re feeding it.

To my left is a 1919 cast iron stove from the Regal Stove Company in Salmon Falls, New Hampshire. This was a revolution in efficiency. You still burn wood, but now you can regulate dampers to control airflow and direct heat where you need it. You still need to understand your fuel, oak versus ash, but the stove gives you more control. The knowledge required drops significantly. The consistency increases.

In front of me is a modern Bosch gas stove. You turn a knob. The heat is instant and consistent. No wood knowledge required. No fuel management. No damper regulation. Just turn it on and cook.

I can view 234 years of technological evolution from one spot in my kitchen.

The open hearth required maximum knowledge and constant attention. The cast iron stove abstracted some complexity but still demanded fuel understanding. The gas stove abstracts almost everything. Most people using a gas stove have no idea what happens when you turn the knob. They don’t need to. The system works.

Until the grid fails. Then the knowledge gap becomes a survival problem.

The stoves teach guidance over force. But they also teach this:

Each generation of technology abstracts away knowledge. The abstraction makes things easier. But if no one documents what was abstracted, the next generation inherits a tool they can’t maintain when the abstraction fails.

What you feed a system matters. What you guide it toward matters more. But what you document about how the system actually works matters most when the easy path breaks.

The fire marshal problem

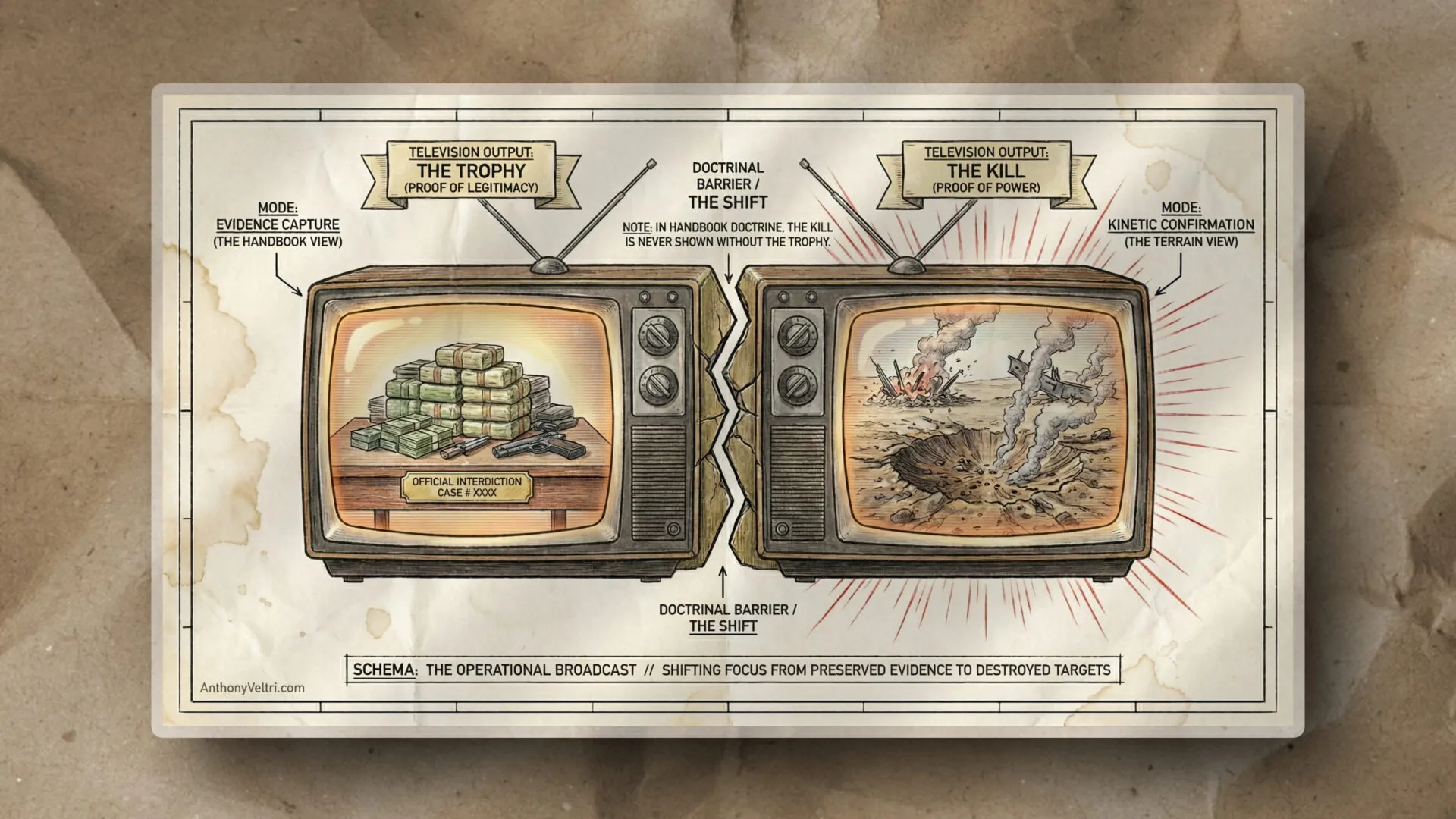

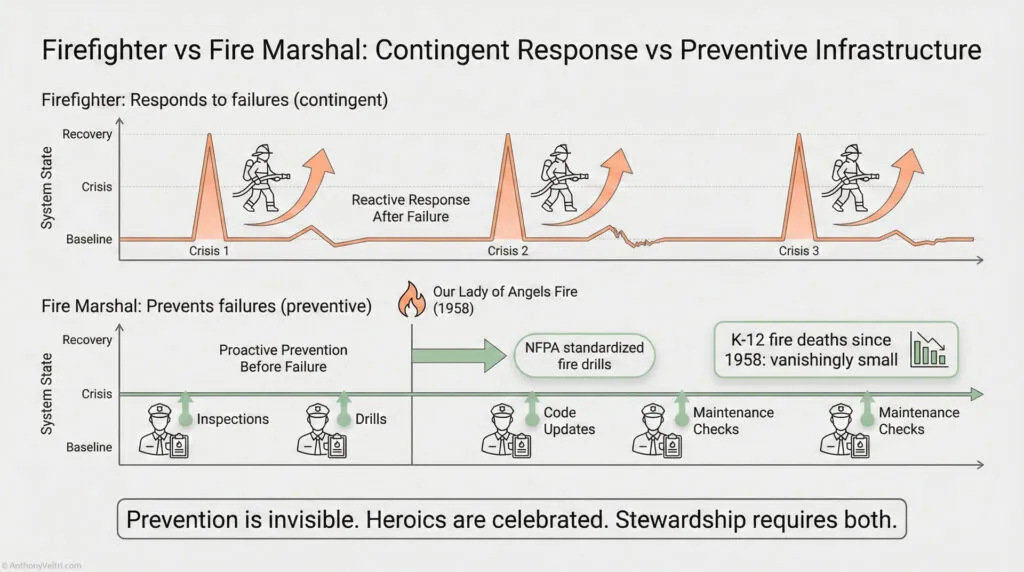

There are no fire marshal calendars for sale.

You can find a dozen different firefighter calendars at any bookstore. Brave men and women in turnout gear, posed dramatically with trucks and hoses. The heroics are visible. The rescues are photogenic. The effort is undeniable.

But fire marshals? They prevent fires. They write codes, conduct inspections, run drills, and design systems so that fires don’t start or can’t spread. When they succeed, nothing happens. And because nothing happens, no one notices.

Prevention is invisible. Heroics are celebrated.

On December 1, 1958, a fire at Our Lady of Angels School in Chicago killed 92 children and 3 nuns. The building had no sprinklers, no fire alarm connected to the fire department, combustible interior finishes, and inadequate exits. Fire drills were rare and unstructured.

The tragedy led to sweeping reforms. The National Fire Protection Association developed standardized fire drill procedures, building codes improved, and schools across the country adopted preventive measures that hadn’t existed before.

While we cannot say with 100% certainty that there has been zero K-12 school fatalities from fire since 1958, we can say that whatever that number is, it is vanishingly small.

Safer than flying. Safer than shark attacks. Safer than almost any other risk category we measure.

Not because firefighters got better at fighting fires in schools. But because fire marshals got better at preventing them.

The NFPA didn’t orchestrate every fire drill in every school from a central bunker. They provided federated doctrine. Schools adopted it. Administrators, teachers, and even special needs students learned the pattern. Everyone knows what to do when the alarm sounds because the knowledge was documented, standardized, taught, and practiced.

That’s prevention as infrastructure. That’s fire marshal thinking. That’s stewardship.

And nobody made a calendar about it.

The Chicken Palace and the burden of undocumented gifts

When we moved to the farmhouse, we inherited five acres. Part of the land had good infrastructure. Part of it needed work. We decided to raise chickens.

I didn’t just build a coop. I built what my kids now call the Chicken Palace. Twelve feet by six feet, elevated on concrete piers about a foot off the ground. The elevated design keeps predators out from below without needing additional barriers. Roof overhang for weather protection. Multiple nest boxes. Roosting bars at the right height. Hardware cloth on the upper portions for ventilation in warm months, with plastic panels we add over the openings in winter. An automatic chicken door that opens at sunrise and closes at dusk. Solar panels to power the door and keep the water from freezing.

It’s tall enough that I can stand inside comfortably. It’s not built to contractor grade, but it’s a palace nonetheless. It works. The chickens are healthy and productive.

But here’s the problem: if I’m the only one who knows how to maintain it, I didn’t build them a gift. I built them a burden.

If they don’t know how to check the concrete piers for settling, the structure will tilt and doors won’t close. If they don’t know how to maintain the automatic door mechanism, they won’t be able to fix it when the sensor fails. If they don’t know how the solar system works, they won’t know what to do when a panel stops charging or the battery needs replacement. If they don’t know when to swap the plastic panels for hardware cloth seasonally, the chickens will either freeze or overheat.

I can build the best chicken coop in three counties, but if my kids can’t maintain it after I’m gone, I’ve imposed a liability on them.

This is the Chicken Palace Principle: Build + Document + Teach Maintenance.

It’s not enough to build well. You have to teach the next generation how to maintain what you built. Otherwise, you’re passing forward infrastructure they’ll have to abandon because they can’t keep it running.

The families before us in this house understood this. They didn’t just leave tools in rafters. They used them in front of their children. They showed them how to sharpen a scythe, regulate a stove, maintain a plumb wall. The knowledge was transferred hand to hand.

Then a generation came that didn’t think they needed those skills anymore. They had modern tools. Electric heat. Gas stoves. Why learn to split wood or sharpen hand tools?

That generation broke the chain.

Now we have a 1919 cast iron stove we’re still learning to operate. We have hand tools we had to research online to even identify. We have tacit knowledge gaps that would take decades to fill through trial and error.

The infrastructure survived. The knowledge didn’t.

That’s bad stewardship.

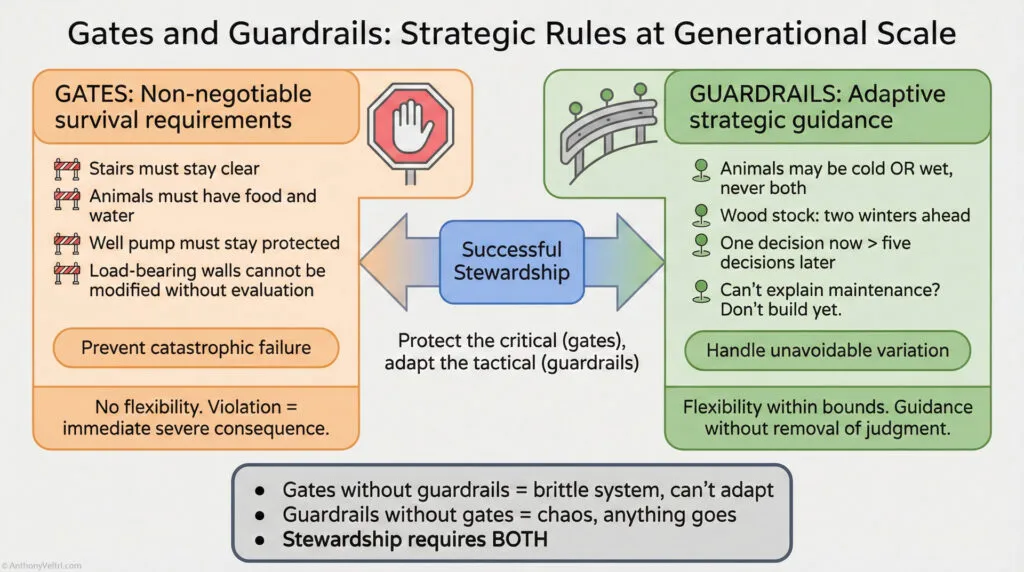

Gates and guardrails at generational scale

When you’re stewarding something across generations, not years, you have to think differently about rules.

Some rules are ironclad. I call these gates. They don’t flex. They don’t adapt. They’re non-negotiable because the consequences of violation are immediate and severe.

Our gates:

- Stairs must be kept clear at all times

- Animals must have food and water available at all times

- The well pump electrical must stay protected from weather

- Load-bearing walls cannot be modified without structural evaluation

These aren’t suggestions. They’re survival requirements.

But most rules aren’t gates. They’re guardrails. They provide guidance without being absolute. They help you make better decisions without removing all flexibility.

Our guardrails:

- Animals may be cold. Animals may be wet. But animals may never be cold and wet simultaneously.

- Wood stock should stay two winters ahead (you’re burning last year’s wood, this year’s is seasoning, next year’s is cut and stacked).

- One decision now that prevents five decisions later is almost always worth it.

- If you can’t explain how to maintain it, don’t build it yet.

Guardrails let you adapt to conditions. Gates keep you alive.

In Doctrine 11: Preventive Action and Contingent Action Must Both Be Designed, I wrote about how resilient systems need both preventive scaffolding and contingent scaffolding.

Stewardship at generational scale works the same way:

- Gates are preventive. They reduce the probability of catastrophic failure.

- Guardrails are contingent. They help you handle unavoidable variation.

You need both. Gates without guardrails create brittle systems that can’t adapt. Guardrails without gates create chaos where anything goes.

The families before us in this house knew this intuitively. They didn’t write policy manuals. But they had patterns:

- Gate: The well must stay functional (survival requirement).

- Guardrail: The well location can move if conditions demand it (three different wells on this property over 234 years).

- Gate: The roof must shed water (survival requirement).

- Guardrail: The roofing material can adapt to what’s available (thatch to wood shingles to asphalt to metal over time).

They protected the mission (shelter, water, food) with gates. They allowed adaptation with guardrails.

That’s stewardship thinking: protect the critical, adapt the tactical.

The digital arsenal and generational optionality

I have three children. Each of them has a domain with their exact name. My daughters have their maiden names secured.

They’re young. They don’t know what to do with these domains yet. They might never use them. That’s fine.

I didn’t buy the domains because I know what they’ll need. I bought them because I don’t.

In 10 or 15 years, when they’re establishing careers, they’ll have clean digital real estate. No wedding photographer in Toledo squatting on their name. No SEO spam site. No identity confusion. They own the namespace. They can build on it, redirect it, or sell it.

But most importantly: they have the option.

This is the same pattern as the Chicken Palace, the scythe, the farmhouse itself. I’m not giving them finished products. I’m giving them infrastructure they can maintain and adapt.

The domains are like the tools in the rafters. Small, durable, waiting for the generation that needs them.

But here’s the critical part: I’m also teaching them how to maintain these things.

- They know how to renew a domain.

- They know how to point DNS records.

- They know what a registrar is and why it matters.

- They understand digital ownership isn’t the same as physical ownership.

I’m not assuming the next generation will “just know.” I’m documenting and teaching the maintenance.

The same applies to this doctrine manual you’re reading right now.

I’ve documented 20 years of work not because I think it’s brilliant, but because the patterns are useful and the next practitioner shouldn’t have to rediscover them from scratch.

Federation vs integration. Contingent vs preventive. Named stewards. Two-lane architecture. Guardrails over gates.

These patterns emerged from real work under real constraints. They survived contact with reality. They’re not theoretical frameworks. They’re operational infrastructure.

If I don’t document them, they die with me. That’s bad stewardship.

The Great Pyramids are still there. The knowledge of how to build them isn’t. I’m trying not to make that mistake.

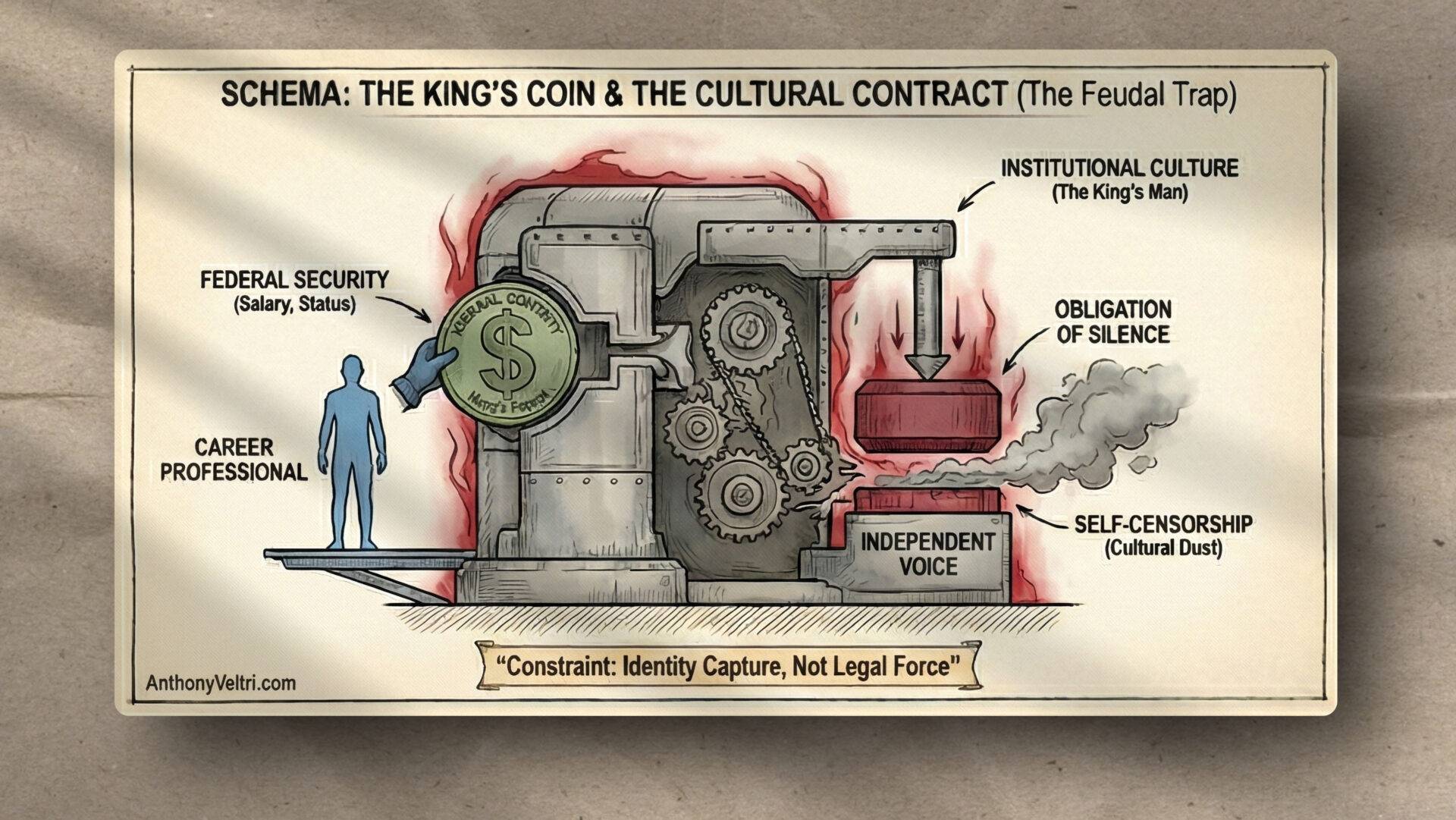

Stewardship demands loyalty to mission, not org chart

In September 2018, I deployed to Hurricane Florence. A few days before my return flight, I developed a sore throat. By the time I landed, I could barely lift my equipment cases. I was hospitalized with Guillain-Barré syndrome after contracting West Nile virus during the deployment.

Recovery took five years. The workers’ compensation fight took even longer.

During that experience, I had what I now call a “Semmelweis moment.”

Ignaz Semmelweis pushed hand washing in hospitals in the 1840s, long before germ theory was accepted. He had the data. He had the evidence. He could show that maternal mortality dropped dramatically when doctors washed their hands between autopsies and deliveries.

His colleagues rejected it. It was uncomfortable. It implied they had been killing patients. The medical establishment pushed back so hard that Semmelweis ended up in an asylum.

But lives were saved. The pattern worked. The truth survived even though the messenger didn’t.

Stewardship sometimes requires raising uncomfortable truths because you’re responsible to the mission, not just to current management.

Recently, I raised a project risk that was uncomfortable to name. It wasn’t about me. It wasn’t about protecting my position or my reputation. It was about the outcome and the people depending on it.

That conversation opened a better path for the team. Not because I was heroic, but because stewardship means loyalty to the mission rather than loyalty to the org chart.

If you see structural problems and say nothing because it might hurt your standing, you’re not stewarding. You’re preserving your position at the expense of the system.

The families who lived in this house before me made hard choices. They adapted when conditions demanded it. They protected what mattered. They passed forward what they could.

They didn’t always get credit. Most of them are forgotten. Their names aren’t on plaques.

But the house is still standing.

That’s stewardship. The infrastructure survives whether or not you get recognized for maintaining it.

What stewardship actually demands

Standing in my kitchen, looking at three generations of cooking technology, I see the pattern clearly now:

Stewardship is preparation over effort.

Sharpen the edge before you need it. Don’t rely on grip strength when the blade is dull. Prevention reduces the probability of failure. The fire marshal prevents fires. The firefighter fights them. Both are necessary, but prevention is invisible and undervalued.

Stewardship is guidance over force.

Airflow matters more than fuel volume. What you feed a system matters, but what you guide it toward matters more. Gates protect the critical. Guardrails allow adaptation. You need both.

Stewardship is documentation over tacit knowledge.

The Great Pyramids teach us what happens when a generation assumes the next will “just know.” Build the Chicken Palace. Then teach your kids how to maintain it. Otherwise you’re imposing a burden, not passing forward a gift.

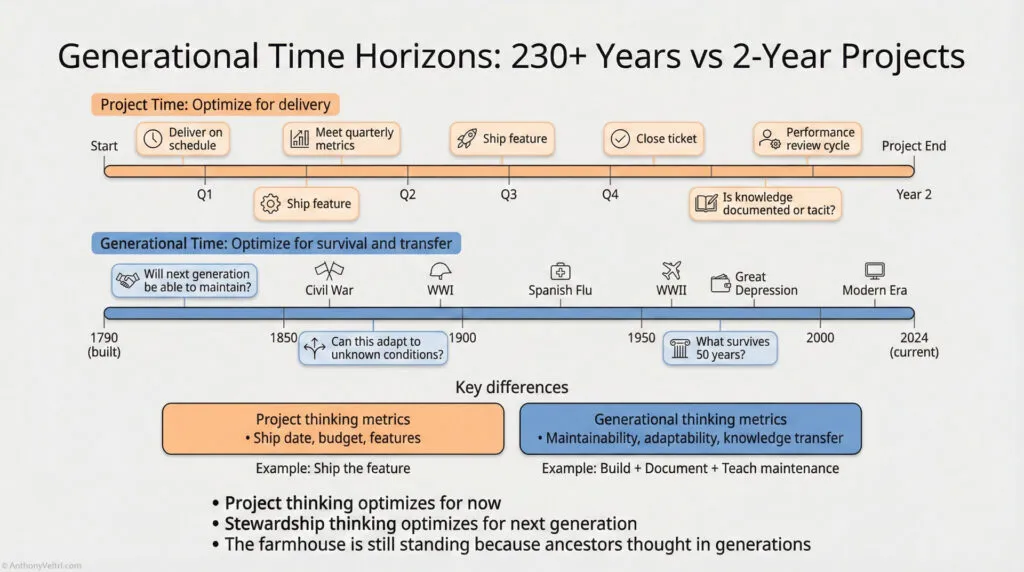

Stewardship is generational thinking over project thinking.

This house is 234 years old. The families before me weren’t optimizing for quarterly results. They were thinking in decades. In lifetimes. In what could be passed forward. The domains for my kids. The doctrine for practitioners. The tools in the rafters. Infrastructure that survives whether or not anyone remembers who built it.

Stewardship is loyalty to mission over org chart.

Semmelweis moments are uncomfortable. Raising risks that leadership doesn’t want to hear is dangerous. But if you see structural problems and stay silent to protect your position, you’re not stewarding. You’re preserving yourself at the expense of the system.

Stewardship is teaching maintenance, not just doing it.

The generation that broke the chain didn’t maliciously destroy knowledge. They just didn’t think they needed it anymore. Modern tools. Electric heat. Gas stoves. Why learn to split wood?

Then the grid failed. And the knowledge gap became a survival problem.

Don’t assume the next generation will have what you have. Don’t assume the abstractions will last. Document how things actually work. Teach the maintenance. Pass forward the infrastructure AND the knowledge to keep it running.

The human condition

We inherit systems we can’t maintain. We receive tools without instructions. We’re given infrastructure that worked for the builders but breaks when we touch them because no one documented the tacit knowledge required to keep it running.

That’s the human condition, at least in today’s day and age.

The 1790 farmhouse chose us. We chose to answer with care. Not because we’re exceptional stewards, but because we finally understood what stewardship actually demands.

It demands preparation over effort. Prevention over heroics. Documentation over tacit knowledge. Generational thinking over project thinking. Teaching maintenance over doing it yourself. Loyalty to mission over org chart.

It demands that you ask hard questions:

- Can the next generation maintain what I’m building?

- Am I documenting the knowledge or assuming they’ll “just know”?

- Am I protecting the critical with gates while allowing adaptation with guardrails?

- Am I optimizing for recognition or for infrastructure that survives?

The families before me in this house didn’t get calendars made about them. Most of them are forgotten. But the house is still standing because they did the work anyway.

That’s the model.

Build infrastructure. Document how it works. Teach the next generation to maintain it. Pass it forward whether or not anyone remembers your name.

The infrastructure remembers. That’s enough.

Doctrine Extractions

This field note connects to existing doctrine:

- Doctrine 11: Preventive Action and Contingent Action Must Both Be Designed: Fire marshal thinking (preventive) vs firefighter response (contingent). Stewardship requires both.

- Hoover Dam Lessons: Named Stewards: “Proudly Maintained By Mike E.” Pride as control measure. Stewardship requires visible ownership.

- Systems Built on Heroics Are Brittle: Capacity over heroics. Stewardship designs for sustainable maintenance, not heroic effort.

New concepts introduced in this field note:

- Generational time horizons: 230+ years vs 2-year projects

- The Chicken Palace Principle: Build + Document + Teach Maintenance

- Abstraction risk: Each generation of technology abstracts away knowledge. Document what you abstract.

- Stewardship loyalty: Mission over org chart (Semmelweis moments)

- Infrastructure as inheritance: Domains, doctrine, tools as durable gifts

Last Updated on February 12, 2026