Field Note: The Benchtop Fallacy: Why Inventory Is Not Capability

Scene: The Shelf That Keeps Getting Deeper

There is a moment every builder hits where the shelf stops being a shelf.

It turns into an archive. Then it turns into a museum. Then it turns into a liability.

Not because any one item is bad. Most of it was earned. Most of it solved a real problem at a real time. The gear has receipts in the form of wins, recoveries, and “thank God I had that.”

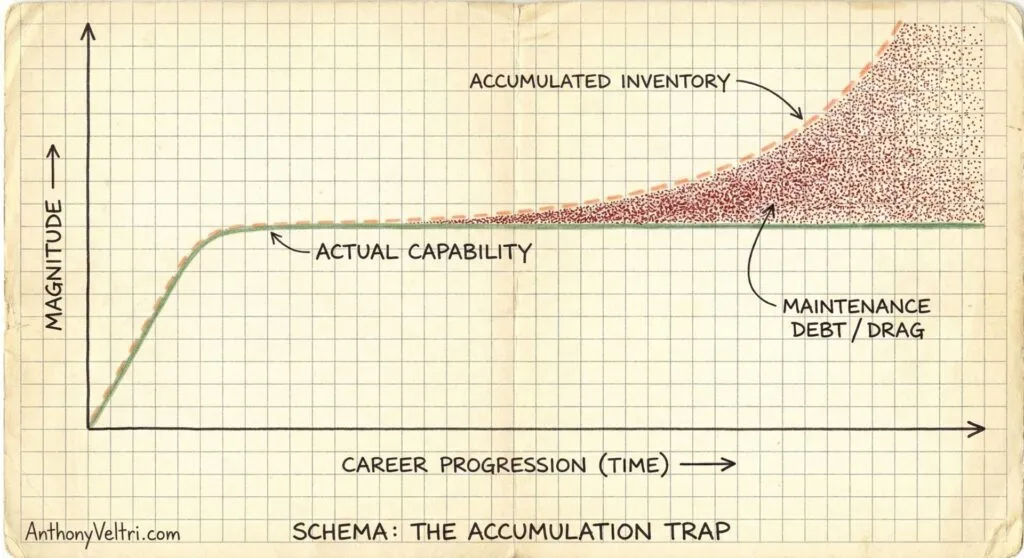

But time does something predictable.

The skill stays. The stuff multiplies.

And eventually, the problem is not that you own tools. The problem is that the tools start owning your attention, your space, your optionality, and your ability to move.

This is a shift from collecting objects to stewarding capability.

The core claim

The value is not in the objects. The value is in the capability.

Objects are how capability expresses itself in the world, but objects are not the capability. If you have the skill, you can usually recreate the toolchain when needed. If you do not have the skill, owning more objects just increases the illusion of readiness. Yes, you need some tools, but at what point does some become a burden?

In other words:

Capability is leverage.

Inventory is drag.

And drag compounds.

Why “multiples” are the trap

Multiples are how a good collection turns into a burden.

It happens innocently.

You buy a second one “just in case.”

You inherit a third one because it would be wasteful to toss it.

You keep the old one because it still works.

You keep the broken one because it is “probably fixable.”

Before long, you are not storing tools. You are storing unresolved decisions.

Multiples also create a subtle cognitive tax: every time you reach for the tool, you have to decide which one you mean. You start negotiating with your own shelf.

The stewardship frame

Stewardship is not minimalism. Stewardship is not aesthetic purity. Stewardship is not punishment.

Stewardship is making sure your environment stays aligned to your current mission and your next likely missions.

It is also a form of respect:

Respect for your future self

Respect for your space

Respect for the people who share that space

Respect for the fact that life changes and “ready for anything” is not the same as “cluttered with everything”

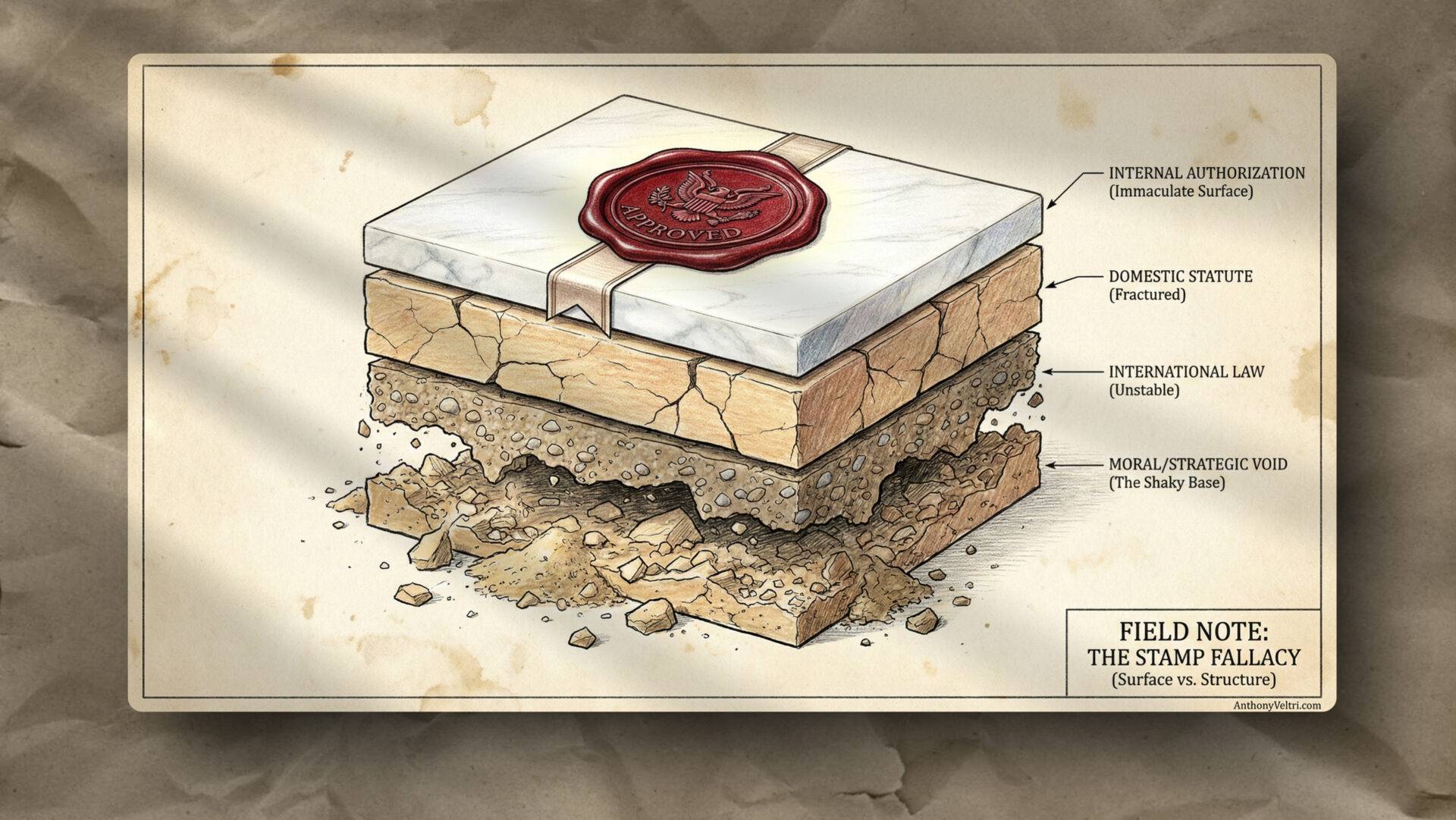

The benchtop fallacy

Most pruning advice assumes a benchtop environment:

good light

clean access

the right posture

time to think

everything laid out

Real repairs are constraint problems. You are under a hood, under a sink, in an attic, in the cold, with a headlamp dying.

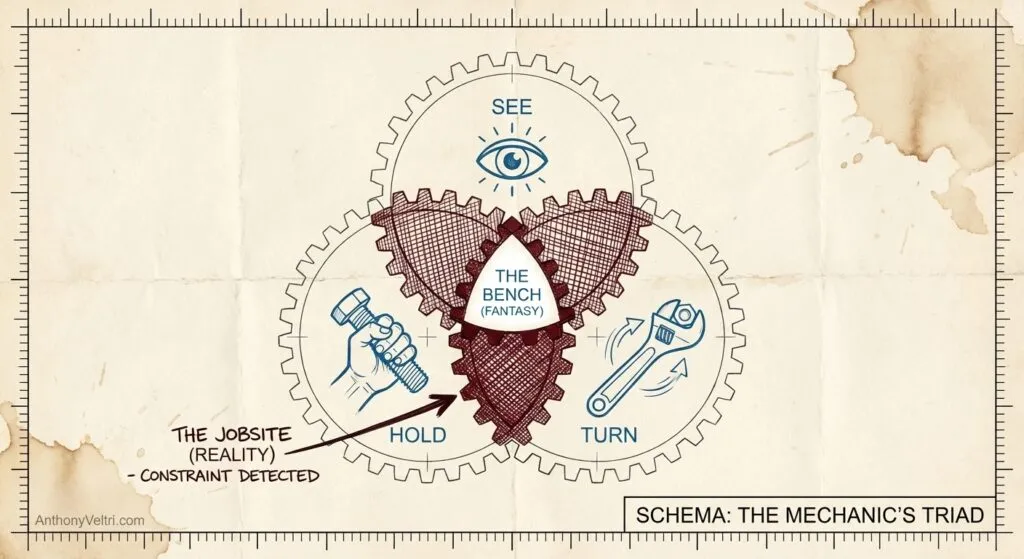

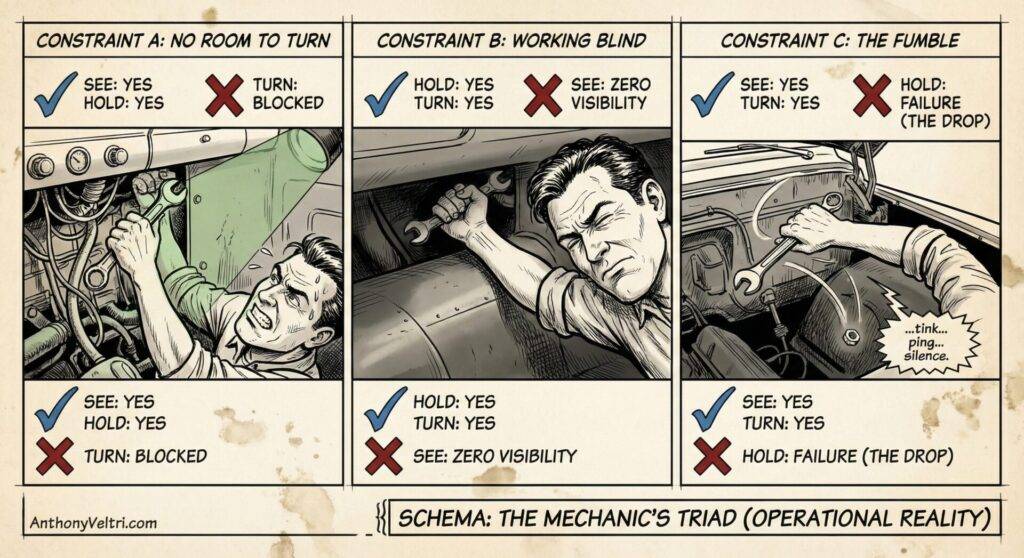

My grandfather (a mechanic) had a rule that shows up everywhere once you notice it:

You rarely get all three at the same time.

You can see it, but you cannot hold it.

You can hold it, but you cannot see it.

You can turn the tool, but you cannot both see and hold.

Most of life is “pick two,” and sometimes you only get one.

The Mechanic’s Triad

Real work rarely happens on a clean bench. Under a hood, under a sink, or in an attic, you usually cannot See, Hold, and Turn at the same time.

👁️ See✋ Hold🔧 Turn

The Rule: Tools -really- earn their place only when they expand capability under this constraint.

This is why tools matter even when the skill stays. Capability is not magic. You cannot will a Robertson bit into existence because you are competent.

So the question is not “Do I need tools or skill?”

The question is: What is the minimum tool coverage that lets my skill express itself in real-world constraints?

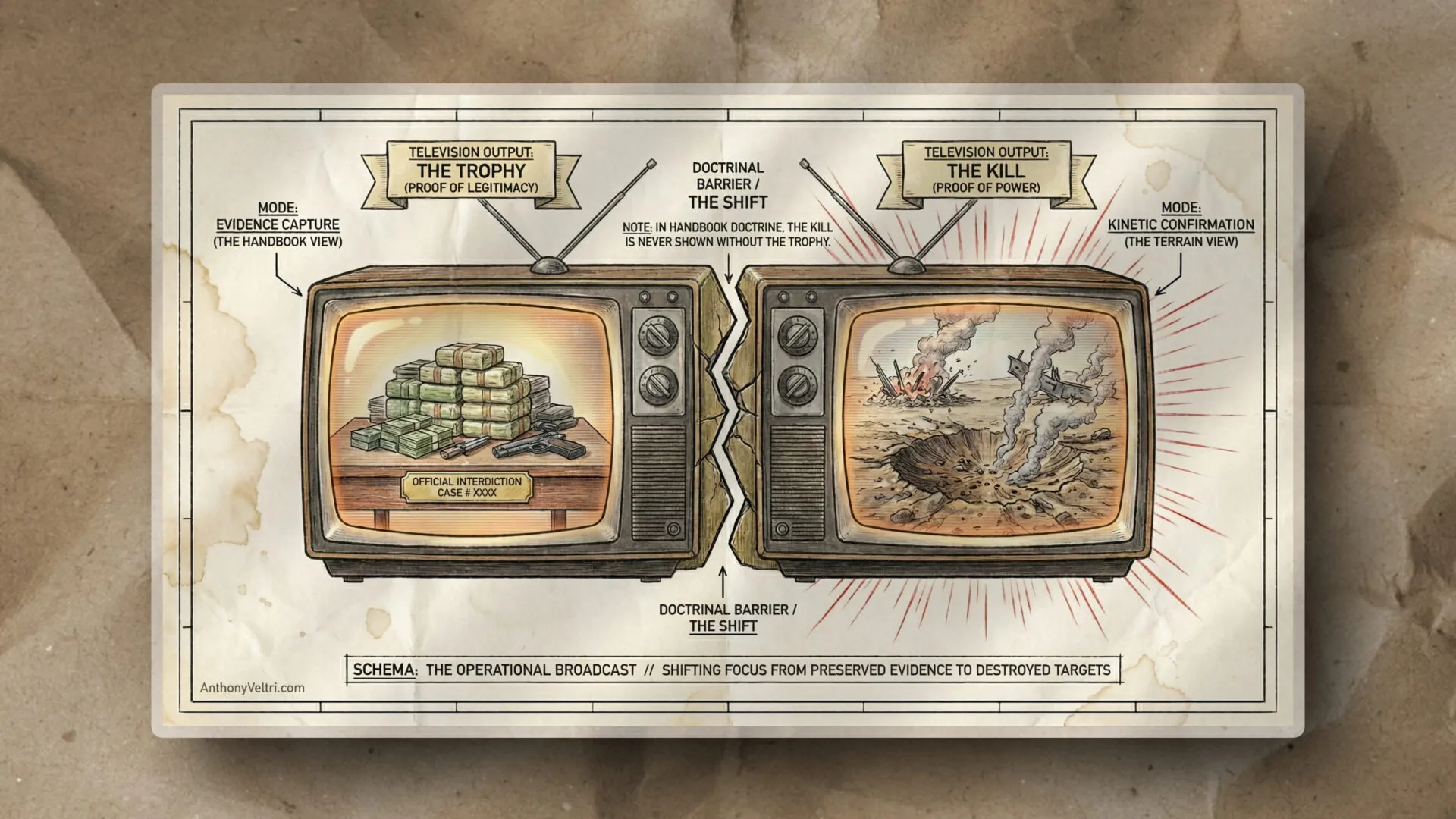

Identity, the backpack, and the stewardship shift

Pruning is not hard because I cannot make decisions about objects.

It is hard because objects become proof.

Proof that I learned a craft. Proof that I survived a season. Proof that I can handle things. Proof that I am the kind of person who is prepared.

So when I pick up an old tool and consider letting it go, my nervous system hears a different question:

Are you letting go of the capability, or are you letting go of the person who earned it?

That is why the process can feel like grief, even when the decision is rational.

The backpack story

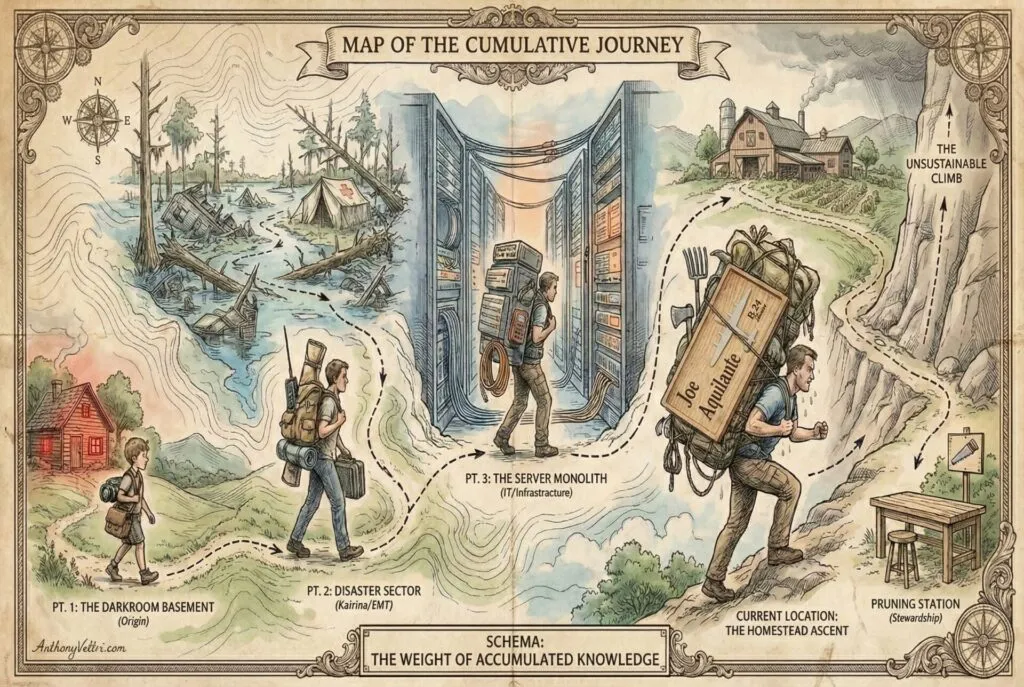

I once heard a story about a man who carries a backpack through his life.

In the first part of his life, the backpack is sacred. He fills it with experience, tools, lessons, and trophies. Each peak adds something. The backpack is how he proves he is becoming someone.

Then, later, he looks up at a new summit and realizes the backpack has quietly changed roles.

It is no longer helping him climb. It is slowing him down.

Not because the items were wrong. Many of them were exactly right for who he was when he earned them. They did their job. They mattered.

But life shifts. The terrain shifts. The mission shifts.

And stewardship becomes a different kind of discipline. It is no longer about adding. It is about choosing what stays in the pack so the next climb is possible.

That story honors the contribution without turning it into permanent storage. It acknowledges that competence can create weight, and that releasing the weight is not the same as releasing the identity.

The stewardship reframe

This is the reframe I use when my identity resists the prune:

The item was part of my development.

The skill is what I keep.

The object is optional unless it expands capability under real constraints.

That last line matters because the bench is the lie.

The jobsite is the truth.

If the item does not help me solve the real-world constraint problem, it is not preparedness. It is inventory.

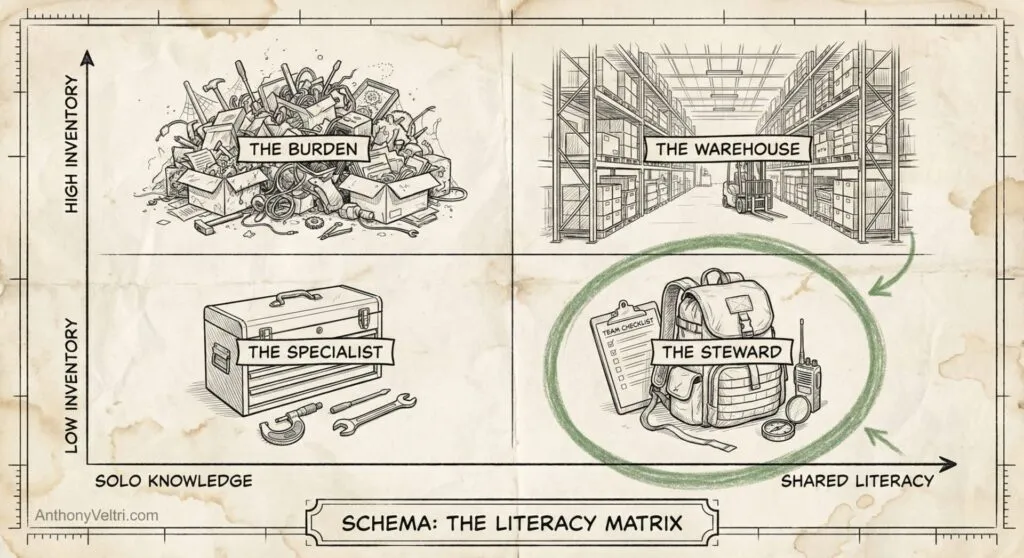

Shared Competence as Forcing Function

Solo stewardship creates accumulation.

Not because you lack discipline. Because you lack the forcing functions that come from shared responsibility.

If you are the only person who can identify the tools, you have created three problems:

- You cannot orchestrate. “Go get the Phillips head” does not work if the other person cannot identify a Phillips head screwdriver.

- You cannot get reality checks. “Do you really need three camera bodies?” cannot happen if the other person does not know what a camera body is or does.

- Sprawl becomes invisible to everyone except you. There is no natural brake. No second opinion. No one trips over your unpacked project and has standing to ask when it gets packed up.

This is not about making everyone an expert. This is about basic literacy.

Basic tool literacy is household infrastructure, the same as knowing where the breaker box lives or how to shut off the main water line.

I taught my kids both. Here is where the master water shutoff is. Here is where the breaker box is. If the basement floods and you think you need to shut off water, kill the power first. Here is how you do it.

But I also taught them: here is what a Phillips head looks like. Here is what a Robertson bit is. Here is where the hand tools live. Here is what this category of thing does.

Not so they can do the work. So they can hand me the tool when I ask. So they can help me decide if we need the tool when I am considering an upgrade. So they can look at three identical camera bodies and ask, “Do we really need all of these?”

The operating room is the right analogy here.

The surgeon holds the scalpel. The OR nurse does not perform surgery. But the OR nurse knows every instrument. What it looks like. What it does. When it gets used. The surgeon can call for it and the nurse can hand it at the right moment.

That is not expertise. That is literacy. And literacy creates accountability.

When only one person holds all the knowledge, that person exists in a permanent state of isolated decision-making. Every choice about what to keep, what to release, what to upgrade, lives entirely in one brain. That brain gets tired. That brain rationalizes. That brain runs out of clock cycles.

Shared literacy distributes the load.

Stewardship versus servitude

There is a difference between shared responsibility and servitude, but sometimes that difference comes down to literacy, not intent.

My grandfather spent years maintaining a house while my grandmother managed the interior. One project was re-siding the house, which would take about four days to complete. She insisted he take down the scaffolding at the end of every day and put it back up the next morning.

If you have never put up traditional scaffolding on a two-story house, you do not have an appreciation for how labor-intensive that is. If you have never tried to put up scaffolding by yourself, you also do not understand that no matter how skilled you are, it still sucks compared to having a team. And putting it up and taking it down at the end of every day sucks compared to moving it only when necessary to work on the next section of the house.

But here is the thing: my grandmother saw my grandfather manipulating the scaffolding with relative ease. He was skilled. He made it look manageable. Often he was the only one setting it up. I would help, or my father would help if we were available, but frequently he worked alone.

Because it looked easy for him, because he was able to make it seem like it was easy, it was perceived as being the same as putting the vacuum away and tidying the kitchen after cooking.

She put the vacuum cleaner away when she was done with it. From her perspective, she was asking for the same standard she held herself to. Put your tools away at the end of the day.

She lacked the literacy to know what she was asking. How much time it took. How much physical effort. How competence can mask difficulty.

And to be fair, he almost certainly lacked the literacy to understand the invisible friction of her domain. He likely made requests of her that felt simple to him but were disruptive to her operational flow, because he didn’t know the ‘scaffolding costs’ of running a household.

That is not tyranny. That is the cost of operating without shared literacy. You can live without that literacy (people do it all the time) but it tends to get heavy after a while. It leaves everyone feeling undervalued because the difficulty of their work is invisible to the person they share space with. One person setting standards without understanding what those standards require. No shared language to negotiate what is reasonable.

That is not tyranny. That is the cost of operating without shared literacy.

My parents operated differently. My father did the technical work. My mother did not swing a hammer, but she contributed. She made lunch. She ran the vacuum. She tidied up the sawdust. Sometimes annoyingly so, even vacuuming around my father while he was actively making more sawdust. But she also understood what he was doing. She had enough literacy to know when a request was reasonable and when it was not.

Different roles, but both engaged. Both literate enough to understand the other’s work. That creates natural forcing functions. The workspace is shared. The project benefits everyone. Everyone has standing to comment on the state of things because everyone understands enough to have an informed opinion.

When a home project benefits the family, the family should participate in some way. Not everyone needs technical skill, but everyone should contribute proportionally to their ability and the benefit they receive. And everyone should have enough literacy to understand what the work actually requires.

Otherwise, you get scaffolding going up and down every day because one person works and another person applies domestic cleaning standards to construction projects without realizing the difference. Not out of malice. Out of ignorance about what the work actually entails.

The training question

If you want shared literacy, you have to create it. It does not emerge on its own.

That means intentional onboarding (teaching). Not lectures. Not nagging. Just moments of transmission. The goal isn’t to create a helper who fetches things. The goal is to create a partner who understands the environment.

‘Here is what this tool is. Here is why we keep it. Here is the problem it solves.’

Then, create low-stakes participation. ‘I need the Phillips head… it’s the one with the star tip. No the four-pointed star. not the 6-pointed star. No, no, my bad, the one that looks like a plus sign. Can you grab it? Perfect! Thank you!’

That isn’t about saving you the walk. It’s about validating their literacy. It proves to them that they know the system. And once they know the system, they have a vote in the system.

Then you actually ask. And you wait while they figure it out. And you do not get frustrated when they hand you the wrong thing the first time.

That is the training. Repetition. Low stakes. Real scenarios.

And once they know, you can ask for help with decisions.

“I am thinking about upgrading this. Do you think we need to keep the old one?”

If they do not know what the thing is or does, that question is meaningless. If they do know, they can give you a second opinion. They can reality-check your justification. They can ask the hard question that you have been avoiding asking yourself.

That is the value of shared literacy. It turns stewardship from a solo burden into a distributed responsibility.

The Upgrade Trap

Upgrade creep is how good tools turn into duplicates.

The pattern is predictable:

You buy a new version with better features.

You tell yourself you will sell the old one.

You keep the old one “just in case.”

Now you have two. Neither decision felt excessive in the moment. One was a legitimate upgrade. One was caution. But together, they create drag.

The old discipline that used to work: sell the old one immediately when the new one arrives.

Why it breaks down:

Your paycheck does not require the sale, so you justify keeping it.

No one else can reality-test the decision because no one else knows what the thing is or does.

The cost of keeping it (storage, organization, mental bandwidth) is not reflected in the purchase price, so it feels free.

It is not free. Storage costs. Organization costs. Decision fatigue costs. And those costs compound.

The test for “keep both”

The question is not “Do I like both?” or “Does the old one still work?”

The question is: Does the old version do something the new version cannot?

If the answer is yes, you have two different capabilities. Keep both.

If the answer is no, you have one capability with a spare. That is upgrade creep, not redundancy.

Example: Let’s say I have two GH7 camera bodies and a GH6. I also have several GH5 bodies from the previous generation. The GH5 bodies still work. They still produce good images. But they do not do anything the GH7 or GH6 cannot do better.

That is not two capabilities. That is one capability with outdated spares. The GH5 bodies need to go.

The commitment device

The discipline is simple: the new item stays in the box until the old item is listed for sale.

But that only works if someone can hold you accountable.

This is where shared literacy becomes load-bearing.

If your family knows what a GH5 is, what it does, and what a GH7 is, they can look at the situation and say, “You got the new one. Let’s list the old one.”

If they do not know, the conversation cannot happen. You are left negotiating with yourself. And yourself is very good at justifying exceptions.

Shared literacy creates natural checkpoints. Someone else sees the new box. Someone else asks the question. Someone else volunteers to help list it.

That external accountability is the difference between a discipline that works and a discipline that quietly erodes over time.

What stays

I keep things for one of three reasons. Anything else is sentimental debt.

It expands what I can do under bad lighting and bad access. If it helps me solve the “see-hold-turn” problem when the world is messy, it earns space.

It covers an interface I actually encounter. Coverage beats duplicates. A single Robertson driver can be more valuable than five extra Phillips.

It is bounded redundancy by location and consequence. Redundancy should be location-based and constraint-based, not drawer-based. One primary. One backup. Everything else must prove it is a different capability, not a different vibe.

A small identity altar is allowed

Some objects are not tools. They are artifacts. They represent chapters.

The mistake is pretending the whole shop needs to be an altar.

So I allow a small, explicit container for identity items. One box, one shelf, one bin. If it does not fit, it is not an identity item. It is a storage problem. Once the altar is bounded, the rest of the space can be honest.

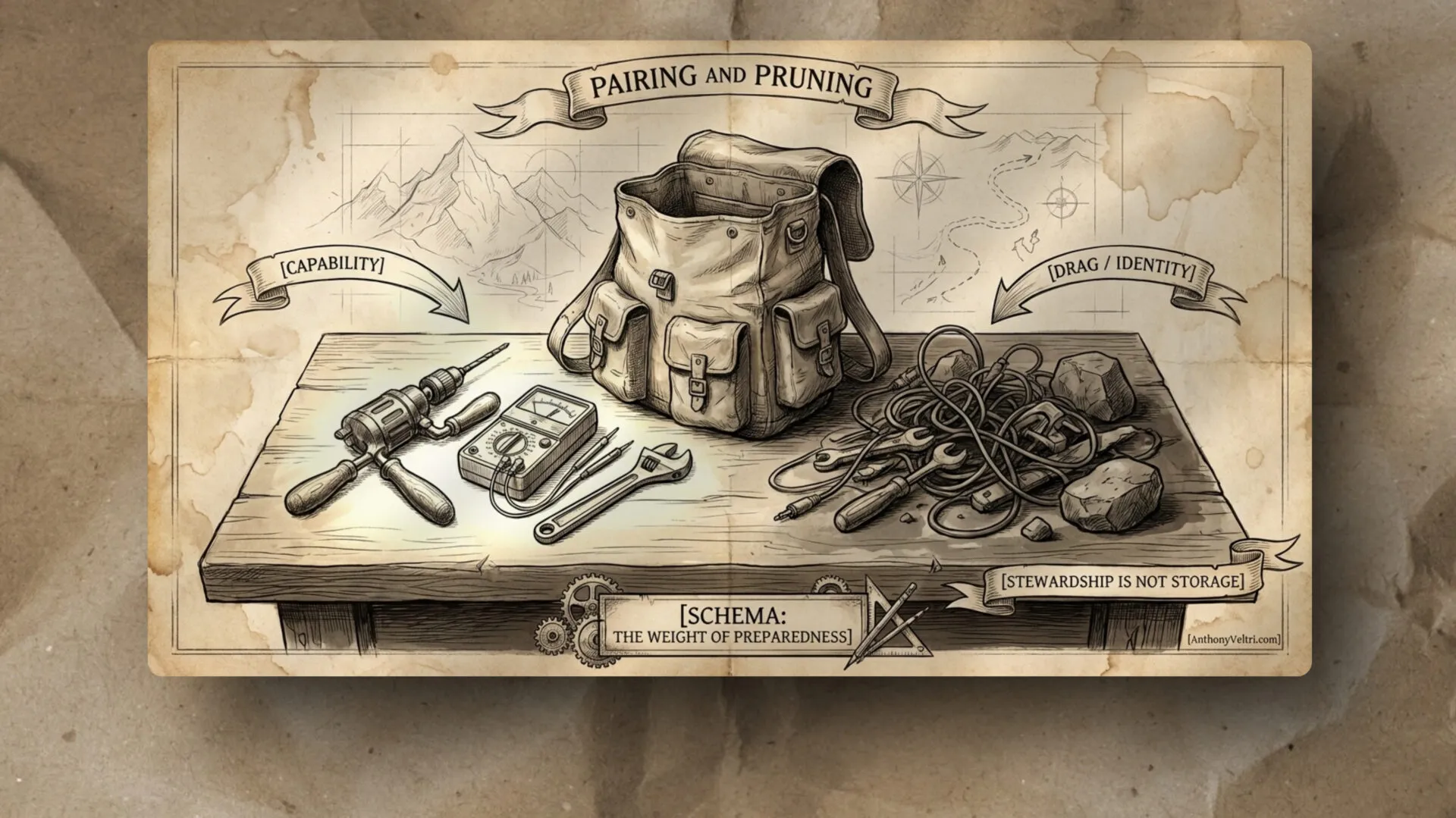

Pairing and pruning

Here is the rule that changed this for me:

Every tool must have a paired reason to exist.

Pair the object to a real use-case, and pair the use-case to a frequency and a consequence.

Frequency: How often does this actually happen?

Consequence: What happens if I do not have it?

This creates four buckets.

Bucket 1: High frequency, high consequence

Keep it. Make it easy to access. Maintain it.

These are your daily drivers.

Bucket 2: Low frequency, high consequence

Keep fewer, but keep the right ones. Store them deliberately. Document where they live.

These are your emergency tools and your rare-but-real scenarios.

Bucket 3: High frequency, low consequence

Keep only if it reduces friction. Otherwise, simplify.

These are convenience tools. They have to earn their space.

Bucket 4: Low frequency, low consequence

This is where the pruning happens.

Sell it, donate it, recycle it, gift it, or release it.

If the scenario is rare and the consequence is small, you do not need to warehouse the solution in your house.

Constraint-based versus exception-based environments

Not all environments require the same redundancy threshold.

A constraint-based environment has predictable variables, full-service access, and urban connectivity. Think: office building, suburban home with next-day delivery, conference room with IT support.

An exception-based environment has unpredictable variables, remote location, and self-reliance requirements. Think: rural winters at minus-18°F, disaster response, wildland fire deployment, remote federal field work.

The calculus is different.

Someone in suburban Atlanta might tell themselves “but what if there is an ice storm and I need that backup generator,” when the actual frequency is once every 15 years and the consequence is “wait a few days for power to return.”

I live in a climate where it routinely goes below zero Fahrenheit. Sometimes double-digit minus. At minus-15°F, water pipes freeze fast. Batteries in your car do not like that very much. Even the lithium ion booster packs do not work at those temperatures. So you need one that lives in the car and one that lives in the house where it stays warm.

That is not paranoia. That is coverage for real, recurring constraints.

The test: How many times in the last three years have I actually needed this category of redundancy versus how many times did I imagine I might need it?

If the answer is “I have never actually needed it but I keep imagining scenarios,” you are probably in a constraint-based environment pretending to be in an exception-based environment.

If the answer is “I have used this multiple times and the consequence of not having it was mission failure or safety risk,” you are genuinely in an exception-based environment and your redundancy threshold is legitimately higher.

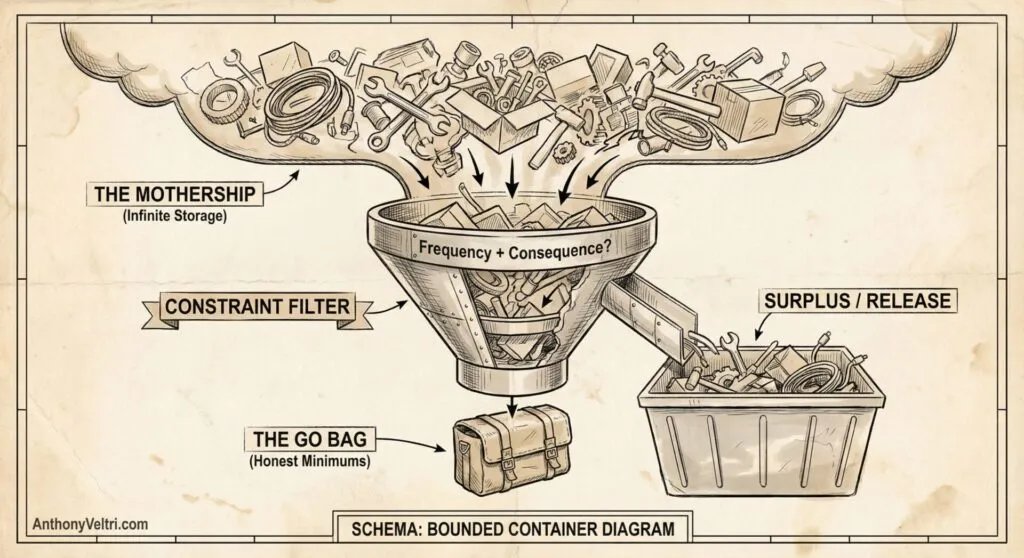

Bounded Containers as Diagnostic

The Go Bag reveals actual minimums through real use.

When I pack for a field job, I cannot bring the entire shop. I bring what I know I will need. One of everything. Maybe a backup for high-consequence items. That is it.

The Go Bag is honest in a way the Mothership is not. The Mothership has infinite expansion room (at a cost that accrues interest). The Go Bag has weight limits, size limits, and the forcing function of “I have to carry this.”

So here is the diagnostic: use existing containers to test actual minimums.

The process:

Identify a functional category. Hand tools. Video cables. Fasteners. Camera gear. Pick one.

Choose the best existing container for that category. Not a new container. Existing inventory. A toolbox. A bin. A bag. A drawer.

Dump the entire category in one place so you can see it all.

Fill the container with the items that pass the frequency/consequence test.

Everything that does not fit is surplus. Sell it. Donate it. Release it.

If you later discover you need something you released, you can add it back. But you also have to remove something else to make room.

Does this work for non-field categories?

Yes.

I have one set of tools that lives in the chicken house area (aka the chicken palace). Another set lives with the lawn mower and snow blower. Those are location-based kits. Different places. Different functions. That makes sense.

The house itself needs a small tool kit so I do not have to walk out to the chicken palace every time I need a screwdriver.

But outside of those bounded kits, we are talking about excess. The Mothership should not be an infinite reserve. The Mothership should be bounded kits plus a small amount of strategic surplus.

The container is the forcing function. If it does not fit, you do not need it, or you have multiples.

The Go Bag plus home coverage rule

For categories where I do field work, the rule is:

One Go Bag (field kit, complete and ready)

One home duplicate (covers household use)

Anything beyond that is surplus unless it serves a different location or a different capability.

If I have enough surplus to make another complete Go Bag, that is diagnostic information. Either I need that second Go Bag for a real reason, or I have been accumulating duplicates.

The test: Would I actually deploy with two complete kits? If no, the surplus goes.

The “skill stays” test

When you feel the anxiety spike, use this test:

If I lost this item in a fire, would I still know what to do?

If the answer is yes, the capability remains. You can rebuild the toolchain later.

If the answer is no, then you are not protecting capability. You are outsourcing capability to an object. That is a different problem, and the fix is training, not hoarding.

The “one good one” rule

Multiples are usually solved by a simple standard:

Keep one good one. Release the rest.

One good drill. One good tripod. One good bag. One reliable cable kit. One labeled bin of the odd adapters.

If you need redundancy, make it explicit and bounded:

One primary

One backup

Everything else goes

Bounded redundancy is preparedness. Unbounded redundancy is clutter dressed up as safety.

The “maintenance debt” audit

Every object you keep has a hidden bill.

It must be stored.

It must be found.

It must be protected.

It must be maintained.

It must be explained to someone else if you are not there. The cognitive tax of ‘Where did I put that?’ is a bill you pay every time you enter the shop.

Storage space and organization space are not the same thing. You can store a large number of wrenches in a cubic foot of milk crate. You cannot organize anywhere near the same number in that same cubic foot of space. The ratio is substantial.

The “Rent vs. Re-Buy” Calculation

The most common objection to pruning is the replacement cost. “If I get rid of this $50 part now, it might cost $80 to replace it in five years. Isn’t keeping it a hedge against inflation?”

Mathematically, usually no. Because objects pay rent.

They pay rent in square footage. They pay rent in organizational supplies. But mostly, they pay rent in Cognitive Load.

Every time you have to move a box of “just in case” items to get to the Christmas decorations, you are paying a toll. Every time you search for a tool and have to dig through three duplicates to find the working one, you are paying a toll.

If you store a $50 item for ten years, you have likely paid $200 in friction, space, and attention to keep it. Buying it again for $80 is not a loss. It is a discount compared to the decade of drag you avoided.

Do not value the object at its replacement cost. Value your space and attention at their current market rate. The space is almost always worth more than the junk occupying it.

A useful question:

Is this item still worth the maintenance debt it demands?

If an object is cheap to replace and expensive to maintain, it is a prime candidate for release.

Selling as Stewardship

Selling stuff properly takes time. Photographing. Listing. Managing inquiries. Packaging. Shipping.

For some items, that time is worth it. For others, it is not.

The triage:

High value: Worth the time to sell properly. List it. Manage it. Get the money.

Medium value: Consignment or estate sale if you have access. Otherwise, donate.

Low value: Donate immediately. The time cost exceeds the dollar return.

Everyone’s threshold is different.

My kids would look at something I consider low-value and say, “No, let me list that. I will take the money.” Their time is worth less than mine right now, so their threshold is lower. That is fine. That is shared stewardship in action.

But the principle holds: if the time required to sell something properly exceeds the value you would get from the sale, donating is better stewardship.

The estate sale reality check

If you do not do the work now, the value goes to zero later.

Estate sales price items high so they do not sell. Then they keep the unsold items and resell them at full value under different conditions. Your heirs get pennies, or nothing.

I have the luxury of time right now. My heirs will not.

So the question is not just “Is this worth money?” The question is “Am I going to do the work to extract that value, or am I going to leave that burden to someone else?”

Leaving it to someone else is not stewardship. It is deferred sorting.

If I am not going to sell it now, I should donate it now and let someone else get the use out of it. That is better than warehousing it indefinitely while telling myself I will deal with it later.

The Dwelling State Trap

Field work has natural closure. The job ends. You pack up. You go home.

Home projects do not. You start a project. You wait for a part. You get interrupted by another priority. The tools stay unpacked. The workspace stays occupied. Days turn into weeks.

This is the dwelling state. Projects in progress with no external deadline and no forcing function for completion.

The Mothership tolerates this in a way the field does not. In the field, you cannot leave your tools sprawled across someone else’s job site. At home, you can. So you do.

The result: permanent unpacked states. Tools that live in limbo. Projects that occupy space indefinitely.

The forcing function is shared space and shared literacy.

If the workspace is shared, other people see the sprawl. If those people have basic tool literacy, they have standing to ask, “When does this get packed up?”

That is not nagging. That is accountability.

If only one person knows what the tools are and what the project is, no one else can comment. The sprawl becomes invisible to everyone except the person doing the work. And that person is very good at justifying why it needs to stay unpacked just a little longer.

Shared literacy makes the dwelling state visible and creates natural checkpoints.

“Are you still working on this?”

“Do you need help packing this up?”

“Can we clear this space for something else?”

Those questions only work if the other person understands what they are looking like. Otherwise, it is just clutter, and clutter does not get questioned, it just gets tolerated.

Work-in-progress limits at home

In manufacturing, kanban systems use work-in-progress limits. You cannot start new work until you finish current work and return the kanban signal.

At home, there is no kanban. There is no external constraint. You can start as many projects as you want.

But shared stewardship creates an informal limit. If the workspace is shared and the tools are understood, other people can see when too many things are in flight.

“You have three projects unpacked right now. Can you finish one before starting another?”

That only happens if shared literacy exists. Otherwise, it is invisible.

A practical process that works

This is the workflow I would actually use, not the fantasy version:

Pick one category. Not the whole house. One category: cables, camera gear, hand tools, camping, office supplies.

Pull it all into one visible pile. This is important. The pile tells the truth.

Choose the standard. “One good one,” or “primary plus backup,” or “this bin only.”

Sort fast, not perfectly.

Keep

Backup

Donate/Sell

Recycle/Trash

Unsure (small box, time-boxed)

Label and containerize the keepers.

Remove the donate/sell items the same day if possible. If not, schedule the removal like a real appointment.

Do one follow-up pass two weeks later. You will see things differently after living with the new shape.

Legacy, heirlooms, and the next generation

This is where pruning stops being a home organization project and turns into a stewardship decision.

Because the hidden fantasy behind a lot of accumulation is not consumerism. It is legacy.

A young man thinks: I will acquire good tools, good gear, good equipment. I will build capability. I will be ready. And someday this will all mean something. Someday it will all get passed down.

Then reality shows up.

If your children do not have the skill, the interest, or the temperament, the “legacy” becomes a burden. It becomes a garage full of decisions they did not make. It becomes the emotional weight of sorting your identity after you are gone.

Even worse, much of what we accumulate is utility-grade, not heirloom-grade. It is made to solve a problem in a particular era, with a particular set of standards, fasteners, batteries, connectors, software, and assumptions. Some of it will be obsolete. Some of it will be incompatible. Some of it will be junk the minute it is unplugged.

So the stewardship question becomes sharper:

Am I leaving them capability, or am I leaving them inventory?

Heirloom versus utility

There is a reason we have a word like heirloom. It implies rarity.

An heirloom is not “anything I owned that still works.” An heirloom is a small set of objects that carry durable meaning and durable usefulness.

Most things are not that. Most things are utilitarian. They are meant to be used hard and replaced. They are not an inheritance. They are consumables with a longer lifespan.

This is a relief when you accept it.

Not everything has to be saved in order to be honored.

The legacy is not the pile

This is the pivot:

The tools were never the legacy. The legacy is the judgment.

Knowing which tool matters under real constraints.

Knowing the difference between coverage and duplicates.

Knowing when redundancy is real versus when it is drawer-based anxiety.

Knowing how to solve the see-hold-turn problem in bad lighting and bad access.

Two lines I want to be able to reuse anywhere:

The best inheritance is not a garage full of tools. It is the ability to choose the right tool under constraint.

Legacy is judgment, not inventory.

That is why pruning can be an act of love rather than an act of loss.

What to pass down

If you want to leave something useful to the next generation, do it on purpose.

A small “ready kit” they can actually use One set. Labeled. Complete. Not a scavenger hunt.

A few true heirlooms Objects with a story and a function that will still matter.

The doctrine Write it down. A single page beats a thousand loose items.

what I kept

why it matters

what it is for

where it lives

what to do if you do not want it

Time and apprenticeship The best inheritance is not a drawer. It is a day together.

Not “here is my stuff,” but “here is how to think.”

The final test

A simple test makes the decision clean:

If my kids inherited this tomorrow, would it increase their capability or increase their burden?

If it increases capability, keep it and document it.

If it increases burden, it is not legacy. It is deferred sorting.

Stewardship means I do the sorting while I am still here, while I still understand the system.

Objections and reframes

“But I might need it.” Reframe: What is the actual probability, and what is the consequence? If both are low, you are paying rent for a hypothetical.

“It would be wasteful to get rid of it.” Reframe: Keeping it unused is also waste. Donating it transfers value to someone who will actually use it.

“I spent money on that.” Reframe: The money is already spent. The new question is whether you want to keep paying with space, attention, and maintenance.

“This reminds me of who I used to be.” Reframe: Keep a small, intentional set of identity artifacts. Do not let the entire tool inventory become a shrine.

What nimble looks like

Nimble is not empty. Nimble is responsive.

A nimble environment has these traits:

You can find what you need in under 60 seconds.

Your “ready kits” are obvious and complete.

The floor and surfaces stay clear by default.

You can pack for a trip or a job without scavenger hunting.

Your tools match your current life, not your previous life.

Closing

I used to think the climb was about filling the backpack. Acquire the tool. Add the redundancy. Be ready.

But real readiness is not a pile, and it is not a drawer full of duplicates. Real readiness is coverage, judgment, and the ability to solve constraints when you cannot see, hold, and turn all at the same time.

So I am pruning with respect, not contempt.

I am keeping what expands capability under bad lighting and bad access. I am bounding redundancy by location and consequence. I am keeping a small space for identity, and refusing to turn the entire shop into an altar.

Because the best inheritance is not a garage full of tools. It is the ability to choose the right tool under constraint. Because legacy is judgment, not inventory.

And because the bench is the lie.

The jobsite (and the home) is the truth.

Last Updated on January 12, 2026