Field Note: When Everyone Uses the Same Words But Means Different Things: Why Integration Fails When Vocabulary Collapses

The previous Field Note (Integration Confusion) diagnosed the pattern: why we keep building technical connectors but getting operational chaos. This note provides the vocabulary to understand the root cause.

It connects the abstract concepts from Annex L to the specific operational failure modes we see in daily government work (showing where ontology, schema, and cognitive models actually break systems in practice).

The reality is, you can operate for years without these terms. In a single office, words like ‘ontology’ or ‘schema’ often feel like academic distractions. You don’t need them to run a team.

But the moment you need to federate across sovereignty boundaries, these distinctions stop being academic and become mission-critical. Without this vocabulary, it is almost impossible to diagnose why integration keeps failing even when the connectors work.

The most dangerous moment in a project is when -everyone- nods in agreement.

Disagreement is safe because it is visible. The real threat is Vocabulary Collapse: the illusion of agreement where “Urgent” means “5 Minutes” to Sales but “2 Weeks” to Engineering. This briefing argues that before you write code, you must write a glossary. True integration doesn’t just connect wires; it connects dictionaries.

Scene: The Restaurant – A Cognitive Schema Everyone Knows

You walk into a restaurant. You know the script without thinking about it:

- Check in with the hostess

- Maybe wait at the bar if there’s a delay

- Get seated at a table

- Server comes over, takes your order

- Food arrives

- Check comes

- You pay and leave

You didn’t study this. You absorbed it through pattern exposure. This is a cognitive schema (your mental model of expected sequences, roles, and meanings in context).

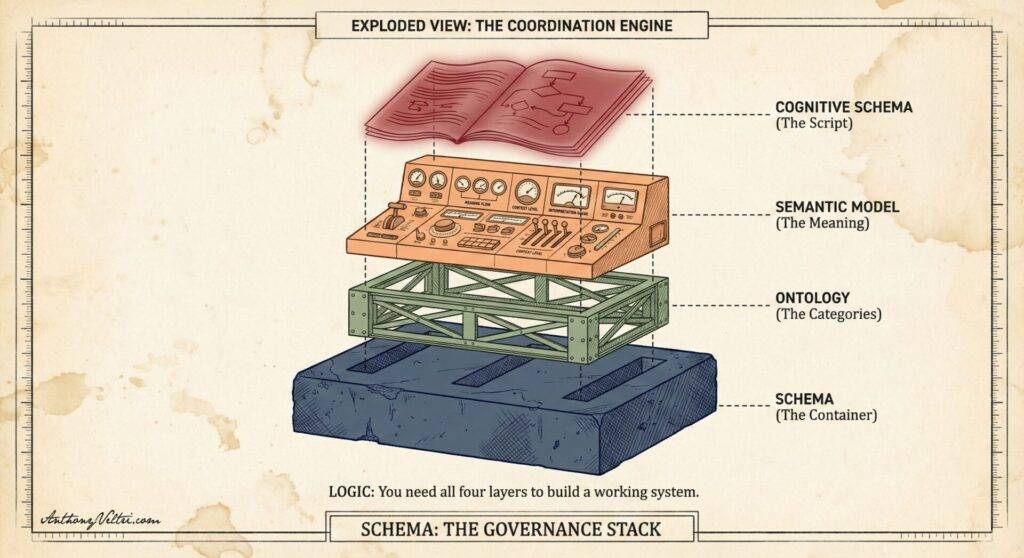

Now let’s break down what’s actually happening beneath that smooth operational flow:

Cognitive schema (the operational script):

- Expected sequence: Check in → wait → seat → order → eat → pay → leave

- Role relationships: Hostess controls seating, server handles food and payment

- Conditional branches: Bar if wait is long, skip if table ready immediately

- Contextual rules: Tipping expected, lingering acceptable after meal, server can interrupt conversation to take order

Ontology embedded within (what things fundamentally are):

- Entities: Hostess, Server, Table, Menu, Order, Payment

- Properties: Table.capacity, Order.status, Server.assigned_section

- Relationships: Server serves multiple Tables, Table has one active Order at a time

- Rules: What makes something a “seated party” versus “waiting party”? Can a table be both occupied and available? What properties must exist for an Order to be “complete”?

Semantic model (what things mean in context):

- Role meanings: Server can interrupt conversation for order, hostess cannot seat before full party arrives

- State transitions: Table goes from Available → Waiting → Seated → Occupied → Cleaning → Available

- Business rules: Cannot seat party larger than table capacity, cannot rush payment until meal complete

- Contextual meanings: “We’re ready to order” means different things said to hostess (ignored) versus server (triggers action)

Database schema (if you were building a reservation system):

- Tables: restaurants, tables, reservations, orders, menu_items, payments

- Field types: table_id INT, capacity TINYINT, status VARCHAR(20), seated_at TIMESTAMP

- Foreign keys: reservations.table_id → tables.table_id

- Constraints: NOT NULL on required fields, UNIQUE on reservation confirmation codes

Why this matters operationally: When you walk into an unfamiliar restaurant, you’re pattern-matching your cognitive schema against reality. If they match, you operate smoothly. If they don’t (order at counter instead of being seated, pay before eating instead of after), you experience cognitive friction until you update your schema.

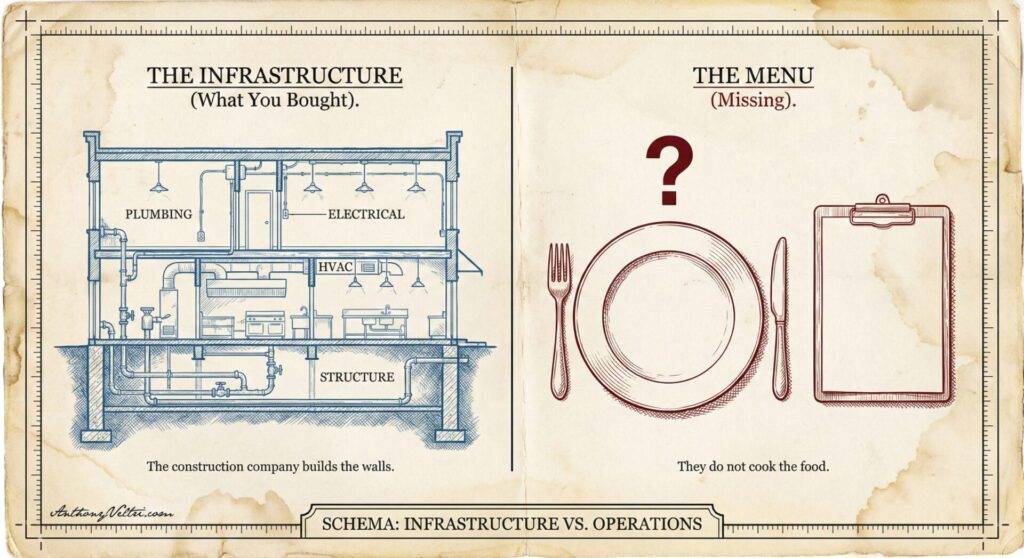

The Construction Company Doesn’t Run Your Restaurant

Now imagine you’re opening a restaurant. You hire a construction company. They:

- Build the restaurant structure

- Design the interior layout

- Hook up utilities (water, electricity, gas)

- Get the occupancy certificate from the city

The building is ready. You move in. Then you realize:

- Nobody developed your menu

- Nobody trained your staff

- Nobody set your coupon policies

- Nobody got your health department certification

- Nobody established rules for how long gift certificates are valid

- Nobody created protocols for handling food allergies

If you went back to the construction company and said: “I don’t understand why this coupon that I want to be only valid for breakfast is being used by my staff for lunch and dinner,” they would look at you like you needed to sit down. That’s not their job. That’s your operational governance.

In the physical world, this distinction is obvious. There’s a bright line between building construction and restaurant operations.

In the IT world, this line is genuinely unclear. When executives ask “isn’t that what we already paid for?” when talking about governance infrastructure, it’s not really their fault. Microsoft 365 is marketed as “your business suite – run your business on this.” That language doesn’t explicitly say “therefore you need nothing else,” but it strongly implies completeness.

The construction company provides the building. Microsoft provides the tenant (the digital building). Your organization provides the apps and tools (the kitchen equipment, the point-of-sale system). Nobody budgets for the operational governance layer (the menu, the staffing protocols, the health certification, the business rules that make it all work together).

That’s the gap. And when organizations federate (multiple restaurants coordinating, multiple agencies working together, multiple companies post-merger), that gap becomes mission-critical.

Break: Why Federation Requires Formal Vocabulary

Solo teams don’t need these terms because shared cognitive schemas work through proximity and repetition. When your team sits together, shares context, and operates from the same mental models, informal vocabulary is fine. “The project status thing” works when everyone knows which thing you mean.

Federation breaks that assumption. You cannot rely on shared cognitive schemas across sovereignty boundaries. Different organizations, different missions, different histories, different mental models for “how things work.”

In a single office, these four concepts blend together seamlessly. You don’t need to distinguish them to get work done.

But under the pressure of federation, they pull apart. If we don’t name them individually, we can’t see which one is breaking. We just demonstrated all four in the restaurant example; now let’s look at how they manifest in actual government failure modes.

Note on structure: We’ll use the Scene/Break/Schema pattern once here to establish it, then let it repeat naturally throughout the examples without calling it out each time. Watch for how the same four concepts (ontology, schema, semantic model, cognitive schema) show up differently in each operational context, and watch for how the absence of vocabulary discipline causes each failure mode.

The Four Concepts That Federation Forces Apart

Ontology: What things fundamentally are. What makes something a “project” versus an “initiative”? Can something be both? What properties must exist for something to count as “active”? This is about agreed definitions of categories and their relationships.

Ontology example: Office of Communications treats “FRN” as public announcement requiring security review and inter-agency deconfliction. Field office treats “FRN” as procedural requirement enabling mission work to proceed. Same term, fundamentally different understanding of what the entity is. One sees it as risk to be managed, the other sees it as gate to be cleared. Integration fails because they’re not actually talking about the same category of thing, even though the schema (fields, tracking systems) might map perfectly.

Schema: How we structure information for storage and transmission. Fields, tables, data types, required versus optional, foreign key relationships. This is the container architecture.

Semantic model: What things mean in context. What states can Project.status transition through? What business rules govern valid changes? When does “blocked” require escalation versus just documentation? This is the scoreboard that shows the numbers.

Cognitive schema: Mental model of expected patterns. Your operational script for “how coordination meetings work” or “how approval processes flow” or “how incidents get managed.” This is the lived experience of how work actually happens.

Note on cognitive schema versus culture: Cognitive schema is not the same as organizational culture, though they’re related. Culture is your values (what you care about, what you prioritize). Cognitive schema is your operational script (the sequence of actions you expect, the pattern you execute). You can have the same culture (safety, accountability, mission focus) but completely different cognitive schemas for how coordination meetings run or how approvals flow. Culture tells you why to coordinate. Cognitive schema tells you how coordination actually happens in practice.

These four concepts do different work, but in practice they blend together until federation forces them apart.

Schema: Federal Register Notifications and the Package Tracking Problem

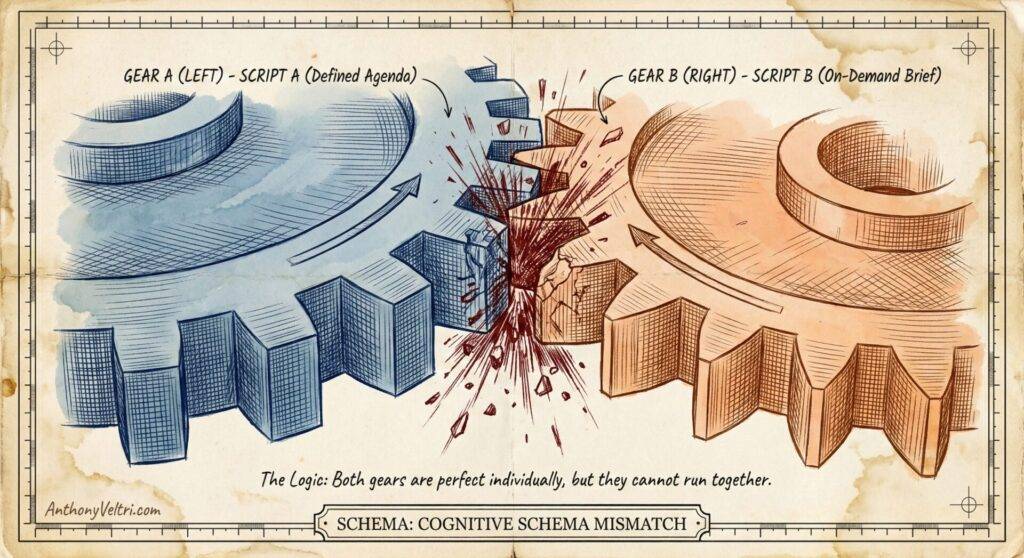

Scene: The Cognitive Schema Mismatch

Forest Service Washington Office, policy coordination with USDA Office of Communications. Fifty to a hundred people on the call. Sometimes more. Every week.

The meeting runs like this: they scroll through a list of reporting entities. When they get to your name (or your office/role), they ask about a Federal Register notification. You don’t know which one until your name is called.

Not “you didn’t know the day before.” Not “you didn’t see the agenda in advance.”

You didn’t know the question until you were live, on the spot, in front of fifty to a hundred people who had their own deadlines, their own leadership chains, their own mission dependencies.

My cognitive schema going in: “They’re going to tell me what they want to be updated on, and I will make sure I can update them on these things.” Standard coordination meeting pattern. I’ve been in hundreds of these.

Their cognitive schema: “We have very important executives on this line, and they are going to decide in the moment what they want to hear about.”

The mismatch: I was expecting a coordination meeting with defined agenda items. They were running an on-demand briefing where the agenda was whatever executives needed that moment. Both patterns are legitimate in their contexts. But walking into their pattern with my expectations was like walking into a restaurant, expecting to be seated by the hostess, but instead they hand you an apron and chef’s hat and tell you you’re needed in the kitchen.

I recognized it immediately. It was awful. I executed the mission every week, but only by brute-forcing the preparation. The pattern fundamentally relies on infinite human preparation to cover for finite systemic ambiguity.

So you prepared for everything. Every week. Five hours of coordination meetings beforehand to cover every possible question about every active FRN in your pipeline. And you weren’t alone. Subject matter experts, regional leadership, Office of General Counsel, Tribal Relations staff, all doing the same preparation cascade.

This wasn’t because people were lazy. This was because of a cognitive schema mismatch combined with semantic conflicts hidden beneath apparently compatible schemas.

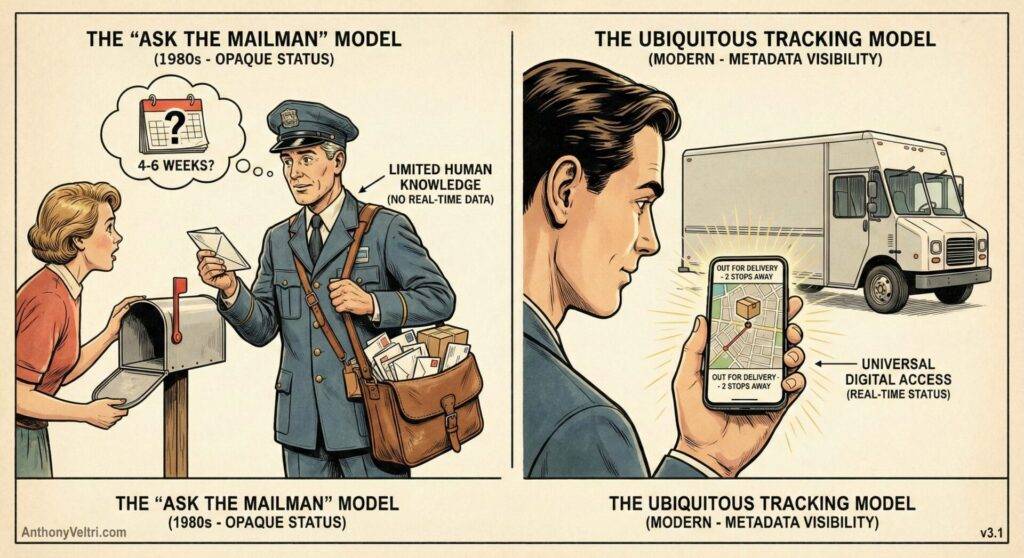

The Package Tracking Analogy

Let me explain the semantic conflicts using a metaphor everyone understands: package tracking.

Forty years ago, if you mail-ordered something from a catalog, the instructions said: “Allow 4-6 weeks for delivery.” You’d mail your order. Then you’d wait.

Imagine a kid checking the mailbox on day 2, asking the mail carrier: “Is it here yet?”

Day 3: “Is it here yet?” Day 4: “Is it here yet?”

The mail carrier knows:

- What’s in the mail bag today (the packages physically with them)

- General delivery tempos (4-6 weeks is normal for mail order)

- That pestering them won’t make packages arrive faster

The mail carrier does not know:

- Exactly where your specific package is right now

- Why it might be spending extra time at a sorting facility in Cincinnati

- Whether it’s delayed or just within normal delivery window

For some people, “I put that in the mail for you” was good enough. They understood the system had inherent delays and checking daily was pointless.

For others, the uncertainty was maddening. They wanted to know: Is it moving? Is it stuck? Is it lost? Should I be worried?

Fast forward to today. We have real-time package tracking. FedEx, UPS, Amazon. You can see:

- Package accepted at origin facility (Jan 10, 2:15 PM)

- Departed origin facility (Jan 10, 8:42 PM)

- Arrived at sorting facility in Memphis (Jan 11, 4:23 AM)

- Departed Memphis (Jan 11, 10:15 AM)

- Out for delivery (Jan 12, 7:30 AM)

- Exception: Delivery rescheduled due to weather (Jan 12, 2:45 PM)

This is exception-based tracking. The system automatically flags when something deviates from expected flow. You don’t need to pester anyone. The infrastructure produces visibility as a default behavior.

Mail carriers around the world probably rejoiced when tracking became available, because they stopped being asked questions they couldn’t answer.

The FRN System Was 1980s Mail Tracking in 2025

Now back to Federal Register notifications.

Field offices send FRNs for naturalist review, technical review, legal review. They know these reviews take time. 4-6 weeks is normal for some stages.

Analysts maintain tracking systems (initially Excel, later SharePoint). They know:

- What’s “in the mail bag” (what FRNs are in the system)

- General tempo for each review stage

- Current status based on last manual update

Analysts do not have real-time access to:

- Why a naturalist review is taking longer (is the naturalist in the field? on vacation? waiting for lab results?)

- Whether an FRN at Office of General Counsel is being actively reviewed or sitting in queue

- If Tribal consultation is progressing or stalled

Executives want to know: Is it moving? Is it stuck? Should I be worried? Is someone forgetting about this?

The semantic conflict: What does “updated” mean?

Field office definition: “Updated = we added new technical information from the naturalist team, or we moved it to the next review stage”

Policy office definition: “Updated = we refined the legal language, or we documented a status change”

Office of Communications definition: “Updated = the status changed in our tracking system”

Executive definition: “Updated = I got visibility into current state recently enough that I trust this isn’t forgotten”

These aren’t just different thresholds on the same timeline. These are different types of “updated” with different operational meanings and different cost functions.

The Three “Delayed” Definitions

Similarly, “delayed” had completely different meanings depending on where you were in the process:

Field naturalist review stage (4-6 week window):

- Package tracking equivalent: “In sorting facility, expected delivery Jan 15-28”

- “Delayed” means: Past the 6-week expected window

- Cost of delay: Slightly pushes downstream timelines, usually absorbed by built-in slack

Office of General Counsel review (days/weeks):

- Package tracking equivalent: “Out for delivery, expected this week”

- “Delayed” means: Past the expected legal review completion date

- Cost of delay: Compression on Federal Register submission timeline, but still recoverable

Federal Register submission (hours/days):

- Package tracking equivalent: “On truck for final delivery today”

- “Delayed” means: Missed the 2 PM Eastern submission deadline

- Cost of delay: Lost a full week. If you miss Federal Register cutoff by one hour, you wait until the next publication window.

Executives asking “why hasn’t this been updated?” in week 2 of naturalist review: They’re seeing no visible movement and interpreting it as potential problem. Actually, everything is within expected delivery window and progressing normally. But without real-time tracking infrastructure, there’s no way to show them “it’s in the naturalist sorting facility, expected completion Jan 28, no exceptions flagged.”

The Heroic Analyst Who Became the System

About a year before this writing, the Forest Service moved from Excel tracking to SharePoint for FRN and Rules & Directives tracking.

The person who made this happen:

- Career USDA analyst with decades of service across multiple roles in the Forest Service, giving him operational insight into how coordination actually worked

- When SharePoint became available, he taught himself in production because it was interesting to him and he had the aptitude

- He built something that worked

- Then he became the system

Important distinction: This wasn’t Shadow IT (unauthorized system operating in secret). This was sanctioned but unsupported IT. The system was authorized, in production, depended upon for mission operations. But it was budgeted as “other duties as assigned” for an analyst, not as a maintained enterprise capability with operational support budget.

His deep operational knowledge (decades across multiple Forest Service roles, understanding how federal coordination flows actually work) made him the only person who could maintain the semantic translation layer. His expertise made him irreplaceable, which made the system fragile.

Not because he was truly irreplaceable (someone else could eventually learn SharePoint), but because his office had no backup. No apprenticeship period. No knowledge transfer plan. Federal hiring rules generally don’t allow “overlap hiring.” You often cannot hire the replacement until the seat is physically empty.

When he retires (which he’s been eligible to do for years), the system doesn’t just lose a worker. It loses its architect, its debugger, and its institutional memory. The organization could revert to manual Excel tracking, or try to hire someone who can inherit and maintain a system with no documentation of the governance logic embedded in its structure.

It’s like opening a restaurant location. The construction company delivered a fully equipped commercial kitchen – industrial stoves, refrigeration, prep stations, all connected to utilities and inspected by the city for occupancy. But nobody developed your recipes. Nobody trained your line cooks. Nobody established food safety protocols. Nobody created the operational systems that turn an equipped kitchen into a functioning restaurant. Then when your head chef (who learned everything through trial and error while operating) decides to retire, you discover you can’t actually serve customers anymore because all the operational knowledge was never documented or transferred.

This is worse than Shadow IT. Shadow IT operates outside approved channels but at least acknowledges it’s unsupported. This system existed in sanctioned production infrastructure (SharePoint, approved Microsoft tenant) but was never budgeted for as actual enterprise capability requiring maintenance resources.

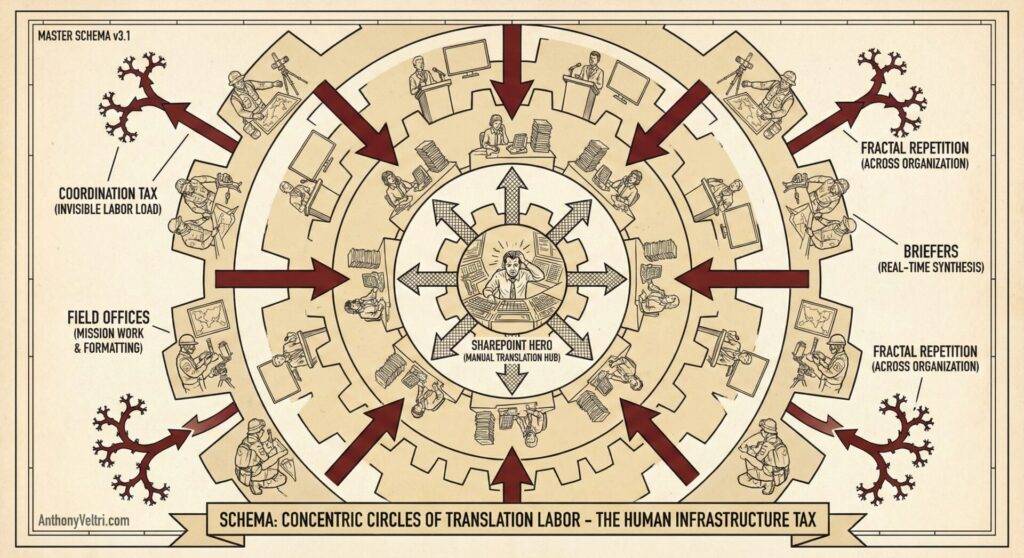

The Concentric Circles of Translation Labor

The SharePoint Hero wasn’t the only person doing invisible translation work. Everyone was.

Think of it as concentric circles of effort:

SharePoint Hero (center):

- Translating between field office definitions and policy office definitions inside the tracking system itself

- Manually investigating status when executives asked for updates

- Maintaining semantic consistency across entries when different people meant different things by the same terms

Analysts (next ring):

- Preparing for weekly coordination call by researching every possible question

- Coordinating with General Counsel on legal language

- Checking with Tribal Relations on consultation status

- Verifying with subject matter experts that technical details were current

- Tracking where each notification sat in regional approval chains

Briefers (next ring):

- Translating on the spot when executives asked unexpected questions

- Synthesizing information from multiple disconnected systems in real-time

- Maintaining composure while essentially being asked to be a human API

Field offices (outer ring):

- Translating their actual work (field research, scientific analysis, operational planning) into whatever format policy office expected

- Responding to status requests when they were in the middle of the actual mission work the FRN was supposed to enable

A Note on Fractal Topology: While this concept and graphic places our SharePoint Hero at the center, in reality, this pattern is fractal. Your organization doesn’t have just one center; it has dozens. Every department likely has its own solar system of translation labor orbiting a different “Hero” who is manually holding their specific process together. We are depicting one instance here, but this structure repeats itself across Finance, HR, Engineering, and Operations. The fragility isn’t isolated; it is distributed.

Everyone was paying the coordination tax because no shared semantic layer existed. And this was repeated across the organization. There were (and are) many Sharepoint Experts, performing “other duties as assigned,” and the organization relies on the heroic efforts of these contributors to deliver mission-essential data and analysis.

The system relied on individual competence to patch interfaces that should have been working but weren’t. When individual excellence becomes load-bearing infrastructure, you’ve built a system that doesn’t just depend on competence – it depends on competent people’s willingness to absorb ever-increasing burden.

The danger isn’t that it punishes competence, but that it creates fragility by relying on competent people to carry loads that should be distributed through proper interface design. Competent people become the path of least resistance for organizational dysfunction. The system learns to rely on them instead of fixing the actual interface problems.

The operational insight: When you see lots of people doing translation work, that’s a governance absence masquerading as individual effort. Schema conflicts look technical. Semantic conflicts look like data quality problems. Ontological conflicts look like categorization work. All three actually manifest as one or more exhausted analysts doing detective work that nobody sees and cannot be automated.

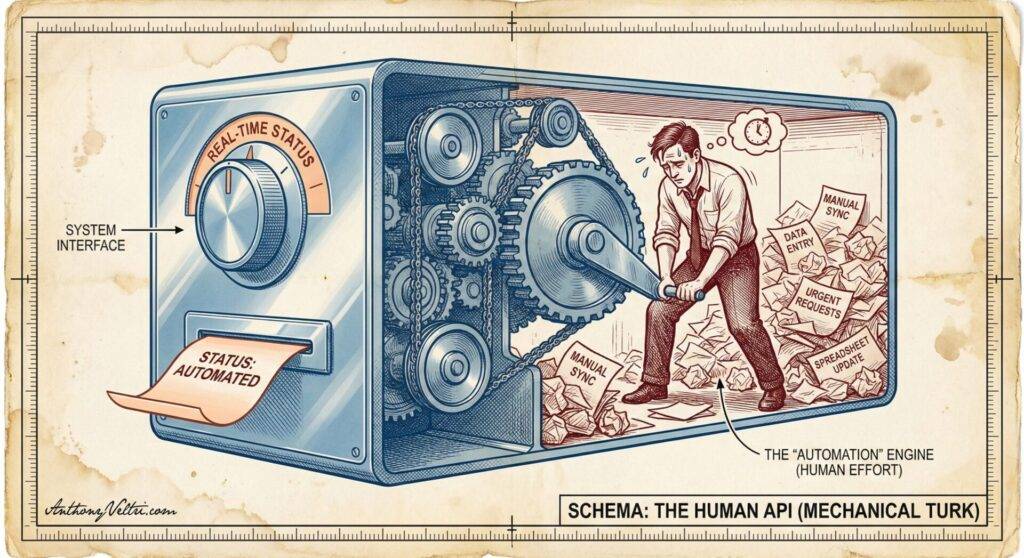

The Mechanical Turk “Real-Time” Tracking System

Here’s what made this sustainable (barely) for as long as it was:

Executives got real-time results. They’d ask a question on the coordination call. Within an hour or by end of day, they’d get an answer. From their perspective, the system was working. They had the visibility they needed.

What they didn’t see: The analyst who spent that hour doing manual detective work. Calling the field office. Checking with General Counsel. Looking up the naturalist’s schedule. Tracking down the Tribal Relations coordinator. Synthesizing all of that into a coherent status update.

This is what I call Mechanical Turk real-time tracking. It looks like a real-time system. It produces real-time results. But behind the interface is a human being running very fast to make it seem automatic.

Real-time tracking infrastructure wants to work once built. It produces updates automatically. Default behavior.

Manual detective work doesn’t want to work. It only produces results because someone is running very fast behind the scenes. It requires constant active human effort to maintain the illusion of systematic capability.

The exhaustion wasn’t just from hard work. Hard work building something valuable creates good exhaustion. Hard work being human glue in a system that lacks automation creates burnout.

And here’s the cultural problem: In government, you can say “the lake froze, we can’t take the boat out to collect samples” and everyone understands physical constraints. But saying “we can’t provide real-time status without building tracking infrastructure” sounds like excuse-making, not resource constraint recognition.

It’s rare as hen’s teeth to hear pushback to executives for things that aren’t physical laws of nature. So people just do it. They become human infrastructure. And the organization learns to expect it.

Why the Office of Communications Couldn’t Share Their Agenda

I need to be very clear here: The Office of Communications was doing exactly what they were charged to do.

They were the final line of defense for the Department’s public voice. They were protecting the Secretary’s intent, ensuring legal defensibility, and preventing policy collision (where one agency accidentally announces something that contradicts another).

They weren’t hiding the agenda to be difficult. They were hiding it because they lacked a mechanism to separate security from visibility.

Some Federal Register items contained sensitive announcements that couldn’t be visible before public release. This was legitimate. A real operational constraint. Data sovereignty that couldn’t be dissolved.

Without a federation architecture (like the FedEx payload/metadata separation model), the only way for them to ensure safety was to lock the doors. They were effectively acting as a manual firewall for the entire agency.

Their cognitive schema made sense from their perspective: Executives on the line with high-stakes decisions. Need flexibility to pivot to whatever is most urgent that day. Can’t broadcast questions in advance because that reveals what they consider high-priority (which itself can be sensitive information).

The problem: Two legitimate operational patterns in conflict, with no technical infrastructure to make both patterns work simultaneously.

What they needed was a system where:

- Field offices could see “FRN #402 exists and is in our queue” without seeing the sensitive content

- Executives could see “FRN #402 status: BLOCKED, owner: Region 3” without exposing what the FRN contains

- Office of Communications could maintain payload security while providing metadata visibility

That’s the “FedEx package” model from Integration Confusion: You don’t need to open the box to know the truck is stalled in Memphis.

What Actually Broke: Governance Absence

Nothing “broke” from a data perspective. The SharePoint system worked. The Excel system before it worked. FRNs eventually got published.

What broke was the analyst who had to go hunt this stuff down manually.

The system placed an ungodly burden on people doing detective work to maintain semantic consistency across incompatible definitions, operational tempos, and sovereignty boundaries.

The compounding drift pattern:

Week 1: Schema looks aligned. Everyone’s using SharePoint. Fields map correctly.

Week 4: Wait, “updated” means different things to different offices. We’re having definitional arguments.

Week 12: Turns out we’re not even tracking the same type of entities. Some “FRNs” are actually Rules & Directives. Categories were fuzzy from the start.

Week 24: Analyst is exhausted. System either collapses when they retire, or gets replaced with new system that will face same problems because governance was never addressed.

If you’re having the same definitional argument every 3 months, that’s not a communication problem. That’s a governance absence.

Governance means:

- Agreed definitions (ontology)

- Enforcement mechanism (schema constraints)

- Named steward (who prevents drift)

- Tempo alignment (when updates expected, what triggers escalation)

Without all four, you get drift. And heroic individual effort fills the gap until it can’t anymore.

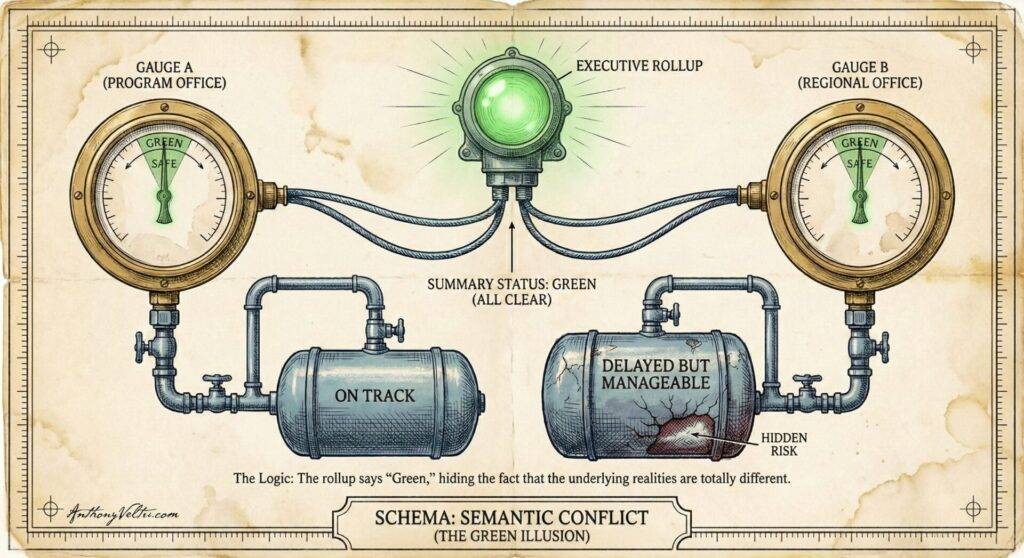

Project Status Rollup: Federal Program Office vs Regional Implementation

Quick example to show this isn’t unique to FRN world.

Federal program office tracks “projects.” By their definition:

- Ontology: Project = temporary initiative, defined start/end date, discrete deliverable

- Semantic model: “Green” = on track to deliver by deadline. “Blocked” = cannot proceed without external dependency.

- Cognitive schema: Weekly updates expected. Escalate yellows to leadership. Reds require executive intervention.

Regional implementation office also tracks “projects.” By their definition:

- Ontology: Project = ongoing program, continuous improvement, evolving scope

- Semantic model: “Green” = no escalation needed, but timeline might slip. “Blocked” = needs executive decision to choose direction between competing priorities.

- Cognitive schema: Bi-weekly updates. Yellows are normal (everything has friction). Only escalate reds.

Integration attempt: Both offices have project_id, title, owner, status, budget, timeline fields. Schema mapping is straightforward. Data flows without errors.

What actually happens:

- Dashboard shows numbers

- Leadership sees 47 projects, 32 green, 12 yellow, 3 red

- Leadership makes decisions based on rollup

- Decisions fail because “green” doesn’t mean the same thing across offices

Program office “green” projects are genuinely on track. Regional “green” projects might slip but don’t need escalation yet. When leadership treats them as equivalent, resource allocation goes wrong.

This is semantic conflict hiding beneath schema compatibility. The scoreboard displays. The numbers are “clean.” But the meaning is incomparable.

And when you try to force alignment (mandate everyone use program office definitions), you break regional operational patterns. They operate differently by necessity, not by choice. Their ongoing programs genuinely can’t be managed with temporary initiative logic.

The only sustainable solution: Federation architecture with shared semantic model. Regions keep their local systems and definitions. But when contributing to enterprise rollup, they translate their local “green” into standardized status with clear definitions that leadership can actually use for decisions.

That translation can happen systematically through Compass-X type infrastructure, or it can happen heroically through analysts doing manual spreadsheet gymnastics every week.

One scales. One breaks.

ICS Coordination: Same Forms, Different Operational Rhythms

One more quick example showing this happens everywhere sovereignty boundaries exist.

Incident Command System (ICS): All agencies use ICS 201 forms, 209 situation reports, standard terminology. Same forms, same fields, same official structure.

Different agencies treat these forms with different operational rhythms:

Some agencies: ICS 201 is living document, updated continuously as situation evolves. Current information expected at all times.

Other agencies: ICS 201 is snapshot-in-time, updated at operational periods (every 12 or 24 hours). Reflects conditions at time of operational briefing.

What happens in Unified Command: Agency A expects real-time updates, keeps checking Agency B’s 201, gets frustrated that it’s “stale.” Agency B is operating correctly according to their doctrine, updating at operational periods. Agency A interprets this as Agency B “not keeping up.”

This is cognitive schema mismatch. Both agencies are following ICS doctrine. But they have different patterns for how frequently the same form gets updated and what “current” means operationally.

Without explicit tempo alignment (governance), the coordination friction shows up as interpersonal conflict (“why aren’t they updating?”) instead of recognized pattern mismatch requiring negotiation.

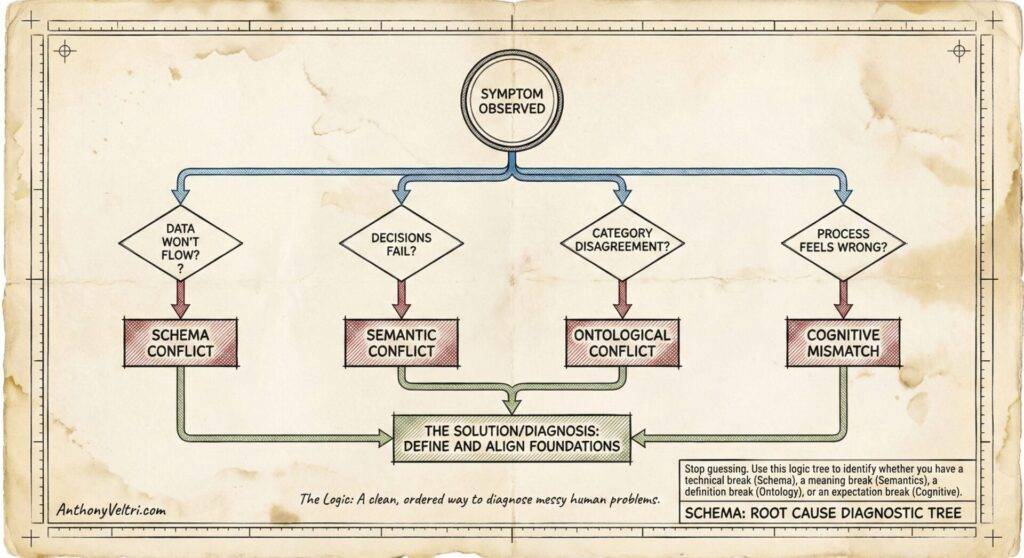

How to Diagnose What You’re Experiencing

Here’s a decision tree to figure out which type of conflict you’re facing:

Start with visible symptom, ask diagnostic questions:

Data won’t flow at all (import fails, API returns errors, CSV won’t load): → Schema conflict → Technical mapping problem → IT can solve with field transformations, data type conversions, ETL work

Data flows clean, but decisions fail (dashboard populates, no errors, but leadership can’t trust the numbers): → Semantic conflict

→ Same labels, different meanings → Requires governance: shared definitions, normalization rules, enforcement mechanism

Can’t agree what categories mean (endless debates about whether something is “project” vs “initiative,” “delayed” vs “on track”): → Ontological conflict → Fundamental disagreement about what things are → Requires conceptual alignment before schema mapping is even meaningful

Meeting feels wrong even when content is fine (everyone technically prepared, agenda exists, but process feels adversarial or exhausting): → Cognitive schema mismatch → Different operational scripts for how coordination works → Requires explicit tempo alignment, expectation-setting, possibly different meeting structure

All of the above + recurring definitional arguments (you solve it once, three months later you’re having same argument): → Governance absence → No enforcement mechanism, no named steward, definitions drift → Requires all four governance components: definitions, enforcement, stewardship, tempo alignment

Recognition-Primed Decision Making and Exhaustion

This connects directly to pattern recognition doctrine. In Recognition-Primed Decision Making (RPD), you’re matching current situation to stored patterns. When your pattern matches reality, you operate smoothly in pattern-recognition mode.

Cognitive schema mismatch breaks pattern recognition. Your stored pattern for “coordination meeting” doesn’t match reality, so you can’t activate the right schema. You’re forced into conscious/deliberate mode, manually processing every interaction instead of operating from pattern.

This is why it’s exhausting. Not just the 5 hours of prep (though that’s real). The exhaustion comes from uncertainty and inability to rely on patterns. You’re manually flying the helicopter instead of letting the plane fly itself.

If coordination should be straightforward but feels draining, check for schema alignment.

Government attracts dedicated people who will follow processes even when inefficient, which is often a feature (consistency, accountability). But it also means people normalize exhaustion as “just how hard work is” instead of recognizing when system design is making work unnecessarily hard.

The distinction: Hard work building something valuable creates good exhaustion. Hard work being human glue in a system that lacks automation is a system design problem.

When you can name “semantic conflict” instead of just feeling exhausted by endless definitional arguments, you can diagnose the real problem and stop trying to fix it with better slide decks.

What Actually Fixes This: Governance Infrastructure

Let me be very clear about what governance means operationally, because the term gets misused.

Governance is not:

- Bureaucracy for its own sake

- Meetings about meetings

- Documentation that nobody reads

- Permission gates that slow everything down

Governance is:

- Agreed definitions (ontology): What do we mean by “project,” “delayed,” “updated,” “blocked”?

- Enforcement mechanism (schema constraints): System won’t let you say “updated” without specifying type of update

- Named steward (ownership): Specific person/role responsible for preventing drift, resolving conflicts

- Tempo alignment (cadence): When are updates expected? What triggers escalation? How do different operational tempos coordinate?

Without all four components, governance stays theoretical. You document standards, then watch them drift because nothing enforces them.

The restaurant construction analogy makes this concrete:

The construction company provides the building (M365 tenant), gets the occupancy certificate (compliance baseline), hooks up utilities (SSO, email, basic collaboration).

You still need menu development, staff training, health certification, coupon policies, gift certificate rules, food allergy protocols. That’s operational governance.

When executives ask “isn’t that what we already paid for?” they’re not wrong to be confused. Microsoft markets M365 as “run your business on this Suite.” That language implies completeness without explicitly saying “you need nothing else.”

The expectation-setting problem is industry-wide. In the physical world, asking the construction company about your restaurant’s menu policies would be absurd. Everyone understands that distinction.

In the IT world, the line between infrastructure and operational governance is genuinely unclear.

Most federal IT is budgeted for the tenancy (the building, the utilities, the occupancy certificate) but not for the operational governance layer (the menu, the protocols, the training). Organizations think: “We bought M365, we’re done. Go do your work.”

It’s rare for an organization to budget for governance infrastructure (not IT security posture governance, but actual “how is this going to be used effectively and not break at the interfaces” governance).

What Enforcement Mechanism Actually Looks Like

Now let’s talk about what enforcement mechanism actually looks like in practice. Remember, governance without enforcement stays theoretical. You can document standards, train people, put policies in wikis – none of that prevents drift if the system allows people to bypass the standard.

An enforcement mechanism means:

- System constrains choices (can’t say “updated” without specifying type)

- Exceptions auto-flag (delays past threshold trigger automatic visibility)

- Rollups maintain meaning (no manual translation required)

- Schema enforces semantics (structure makes consistency automatic)

We built Compass-X specifically to be that enforcement mechanism – the health inspector that enforces the menu, the protocols that make the kitchen produce consistent food regardless of which line cook is working that day.

The benefit of Compass-X is that while most other solutions that offer governance require complete rip-and-replace, Compass-X installs governance infrastructure on your existing Microsoft tenant.

This is critical: Not “most federal IT solutions” but “most federal IT solutions that offer governance.”

Sure, ServiceNow has governance. But now you’re in a whole new vendor ecosystem. Your Microsoft investment is still there, but you’re transitioning to completely new platform. New FedRAMP certification. New Authority to Operate. New compliance overhead. New training. New contracts.

Compass-X goes right on top of your existing M365 investment. No new vendor. No new certification requirements. No throwing away what you’ve already built.

It’s like the construction company having a sister company that says: “You have your building built, interior designed, utilities hooked up, occupancy certificate issued. Let me help you get your health department certification, hire the right people, develop your menu, establish your operational policies. We don’t replace what you’ve invested in. We add the operational layer that makes it all work together.”

[Screenshot showing Compass-X interface with status tracking, constrained status types, automatic exception flagging, and rollup that maintains semantic consistency]

Caption: This is what semantic discipline looks like when it’s enforced systematically rather than heroically. Status types are constrained by schema. Exceptions auto-flag when thresholds are crossed. Rollups maintain meaning without requiring an analyst to manually normalize incompatible definitions every week.

Action Items: What Each Audience Needs to Do

Data Teams

Use this vocabulary to diagnose failures. Stop trying to fix governance problems with ETL.

When leadership asks for integration and you build perfect field mappings but decisions still fail, that’s not a technical problem requiring better connectors. That’s a semantic conflict requiring governance.

Your job is to make data flow. But if “green” means different things in different systems, no amount of ETL sophistication will make that rollup decision-grade. You need to escalate to governance layer, not build more transformation logic.

Learn to recognize: “This looks like data quality issue, but it’s actually definitional mismatch.” Then you can point leadership to the real problem instead of absorbing blame for why the dashboard “doesn’t work” when technically it works perfectly.

Leaders

Budget for the restaurant operations, not just the building. Recognize heroic effort as system design failure signal.

When you see people working extremely hard to maintain coordination, that’s not evidence of dedication (though it is that). It’s evidence of governance absence.

The heroic effort you see isn’t a character flaw. It’s the system’s only defense against interface failures. When individual excellence becomes load-bearing infrastructure, you’ve built a system that creates fragility by relying on competent people to carry loads that should be distributed through proper interface design.

Budget for governance infrastructure. Not just the M365 subscription (the building), but the operational layer (the menu, the protocols, the training). That’s typically 15-20% of what you spent on the technology itself, and it’s what makes the technology actually deliver value.

If you’re funding integration projects every 2-3 years because the last one “didn’t quite work,” you’re not solving the wrong technical problem. You’re avoiding the governance investment that would make integration sustainable.

How do you fix cognitive schema mismatch without replacing everyone? You don’t change people’s mental models through training alone. You make the process explicit. Write down the operational script. Document the expected sequence, the role relationships, the decision points. Then enforce it through system design. When everyone can see “here’s how this meeting works, here’s what prepared means, here’s when escalation triggers,” they can adjust their cognitive schemas to match reality. The governance layer turns implicit expectations into explicit protocol that new people can learn and experienced people can rely on.

Architects

Build enforcement mechanisms, not just documentation. Make the system enforce what the standards promise.

You can document that “updated” requires specifying update type. You can train people on definitions. You can put it in the wiki. None of that prevents drift if the system allows people to bypass the standard.

Your job is to build systems where good behavior is the path of least resistance and bad behavior is harder than just doing it right.

Schema constraints. Required fields. Validation rules. Automatic exception flagging. These aren’t bureaucratic obstacles. These are enforcement mechanisms that let governance scale beyond heroic individual effort.

Don’t just translate between executives and engineers. Build systems that make semantic consistency automatic instead of requiring constant human correction.

Field Practitioners and Analysts

If you’re exhausted by coordination work that should be straightforward, this isn’t a personal capacity problem.

You’re not failing. The system is poorly designed.

Use this vocabulary to show leadership it’s a system design problem requiring infrastructure investment, not individual heroism.

When you’re doing 20 hours a week of detective work to answer “where’s this package?”, that’s not normal workload. That’s you being human infrastructure substituting for missing automation.

When you’re prepping 5 hours for a 30-minute meeting because you don’t know what will be asked, that’s not inadequate preparation. That’s cognitive schema mismatch making pattern recognition impossible.

You deserve systems that make your expertise valuable, not systems that burn your expertise as fuel to compensate for governance absence.

Show this field note to your leadership. Say: “This is what I’m experiencing. The exhaustion isn’t from hard work. It’s from being human glue in a system that lacks proper interfaces. We need governance infrastructure, not more overtime.”

How This Connects to Integration Confusion and Compass-X

Integration Confusion diagnosed the pattern: Why do organizations keep funding integration projects that fail to deliver decision-grade rollups?

This field note provides the vocabulary to understand root cause: Schema conflicts are visible. Semantic conflicts are invisible. Ontological conflicts are fundamental. Cognitive schema mismatches make everything harder. All of them look like they should be fixable with better technology, but they’re actually governance absences.

Compass-X is the proof that governance can be enforced systematically at scale rather than heroically by exhausted individuals.

The through-line:

- Without vocabulary (this note), you can’t diagnose what’s actually breaking

- Without diagnosis (Integration Confusion), you can’t see the pattern repeating

- Without seeing the pattern, you keep buying gym memberships (integration tools) when you actually need a diet plan (governance infrastructure)

Integration Confusion is the problem most organizations see first. They experience coordination pain. They fund integration projects. The projects technically succeed but operationally fail.

This field note is realizing you have a bigger problem. The integration isn’t failing because of bad technology. It’s failing because of governance absence hiding beneath apparently compatible schemas.

Compass-X is the solution infrastructure. Not because Compass-X is the only way to solve it (you could build governance without it if you had budget, time, and political will), but because systematic enforcement at scale requires purpose-built tooling. And unlike solutions that require rip-and-replace, Compass-X installs on your existing Microsoft investment.

Most people go to the gym to get fit. They see the pain. But they don’t realize they also need the diet plan. Integration tools are the gym membership. Governance infrastructure is the diet plan. You need both, but most organizations only budget for one.

Related Reading:

- Field Note: Integration Confusion (the pattern this vocabulary explains)

- Annex L: The Rosetta Stone for Data Teams (the theoretical foundation)

- Doctrine on Recognition-Primed Decision Making (why cognitive schema mismatch is exhausting)

- Doctrine on Federation vs Integration (when each approach applies)

Last Updated on February 11, 2026