Field Notes: Why Facts Don’t Change Minds: Motivation And Story Frameworks For Leaders

Stop Presenting, Start Guiding: How To Use Story Patterns To Drive Behavior Change

When I started doing more video and training work inside government, I realized something important.

The hardest part was not cameras.

It was not editing.

It was not even nervous talent.

It was this:

I could give people accurate information and they still would not care enough to change.

If you are a government leader, a program manager, or a technical expert who suddenly finds yourself on camera or at the front of a room, you have probably felt this too.

You get fifteen minutes on the agenda to explain something you have spent years learning. You pour all the right facts into the slide deck. You check every policy box. You do everything “right” and still walk away with the sense that nothing shifted.

This field note is about two simple frameworks that helped me get past that wall when I was scripting messages for government officials and, later, for business owners. I also want to be clear about something. I have built messages that sounded good and still did not move anything important. In a few cases, I realized later that I had told a cleaner story than the underlying system actually deserved. This note exists in part so I do not repeat that pattern, and so you do not either.

- A motivation spectrum based on how people like to learn.

- A story pattern that has been in use since long before PowerPoint.

You do not have to be a communications professional to use these. In fact, they work best when the person using them is a domain expert who cares deeply about what they are trying to change.

Original video is old, but advice is timeless. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hE-5ObXIaGI

A Quick Word On “Advanced”

I want to be honest up front.

These frameworks are more advanced than the basic planning patterns in the Government Video Guide and the safe beginner on camera ritual.

With many government audiences, I could barely get people to consistently use the basic FAQ, should ask, and “what you really want to know” triad. That alone is transformative if you take it seriously.

The motivation and story frameworks in this note are for those moments when:

- You are willing to put in real practice.

- Your organization is willing to support the effort.

- You are trying to move more than metrics. You are trying to move beliefs and behavior.

If that describes you, keep reading. If not, feel free to come back to this later.

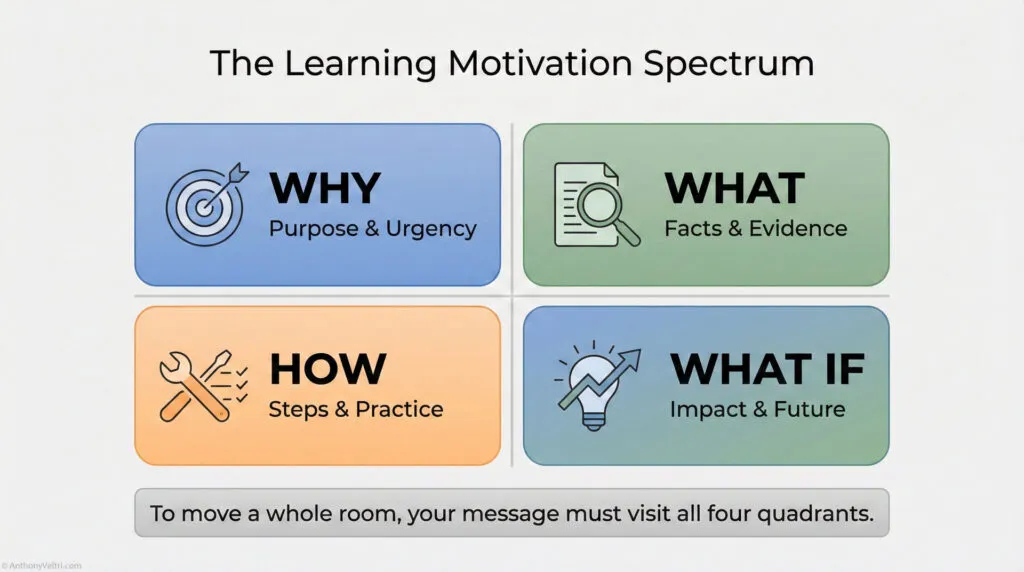

Framework 1: Why, What, How, What If

The first framework is a simple way of thinking about how people are motivated to learn. It is loosely based on classic motivation research, but I do not use it as a formal psychological model. I use it as a design lens.

People tend to cluster in four groups when it comes to learning something new:

- Why people

- What people

- How people

- What if people

No one is just one thing, but most of us have a dominant mode. If you design your content without thinking about these modes, you will reliably lose parts of your audience.

1. Why people

These are the people who want to know:

- Why this

- Why now

- Why them

They need to understand the reason they are being asked to spend time or attention on a topic.

If you skip the “why” and jump straight into instructions or details, this group will disengage. They are not being difficult. They are trying to understand whether this is worth doing at all.

2. What people

These people want to know:

- What exactly is this

- What is the source of the information

- What makes it credible

They are often your scientists, analysts, and policy staff. They care about provenance and definitions.

If you give them a slick story without any “what” underneath it, they will not trust you. They need to see that you know what you are talking about.

3. How people

This is the group that wants to know:

- How do I do this

- How does this work in practice

- How do I apply it on Monday morning

They are your implementers and procedure experts. If you leave out the practical details, they will nod politely and then go right back to what they were doing before.

4. What if people

These are the “big picture” thinkers.

They want to know:

- What does this mean for me

- What does this mean for my unit or my agency

- What does this change about our options

Entrepreneurs and business owners cluster heavily here. They listen to every message with one underlying question:

“Is this going to move the needle for me”

Some senior government officials think this way too, but many rose through roles that rewarded adherence to policy and procedure. They were promoted because they were exceptional at “how” and “what.”

When you talk to them in their official capacity, you mostly meet their “how” and “what” selves, not their “what if” selves.

Designing Messages With The Motivation Spectrum

When I build a message for government or business audiences now, I deliberately walk through all four modes.

For example, imagine a time management initiative inside an agency.

- For the why people, you frame the problem.

- Why this is urgent.

- Why their current patterns are hurting them or their teams.

- For the what people, you define the new approach.

- What it is called.

- What processes and tools are actually changing.

- For the how people, you provide concrete steps.

- How to set up the new system.

- How it will work with existing policy and software.

- For the what if people, you spell out impact.

- What it will mean for their workload.

- What it could unlock for their mission if they stick with it.

You do not need four separate talks. You need one message that hits each mode at least once in a way that feels genuine.

Positive And Negative Motivators

There is a second layer that sits on top of that spectrum.

People are motivated by:

- Positive affiliation

- Positive power

- Positive accomplishment

And they are also motivated by the negative versions:

- Fear of failure or negative accomplishment

- Fear of negative power or loss of control

- Fear of negative affiliation, being excluded or seen as not pulling their weight

You can use this ethically to tell the truth about both sides.

Back to the time management example:

- Positive accomplishment

- “If you master this approach, you will reliably end your day with the most important work done instead of whatever screamed the loudest.”

- Negative accomplishment

- “If you do not get a handle on this, you will continue to burn time on low value tasks and the strategic work will always slip to the edges.”

- Positive affiliation

- “If your whole team adopts this, you will spend less time apologizing for dropped balls and more time doing the work you actually signed up for.”

- Negative affiliation

- “If only a few people adopt it, they will become the bottleneck for everyone else and resentment will grow.”

Used well, this is not manipulation. It is clarity.

Used badly, it absolutely can become manipulation. If you:

- Hide real risks

- Exaggerate benefits you cannot deliver

- Or use fear of exclusion just to keep people in line

You are naming both the future they want and the future they genuinely want to avoid. You are doing it in plain language that ties to their actual world, not abstract slogans.

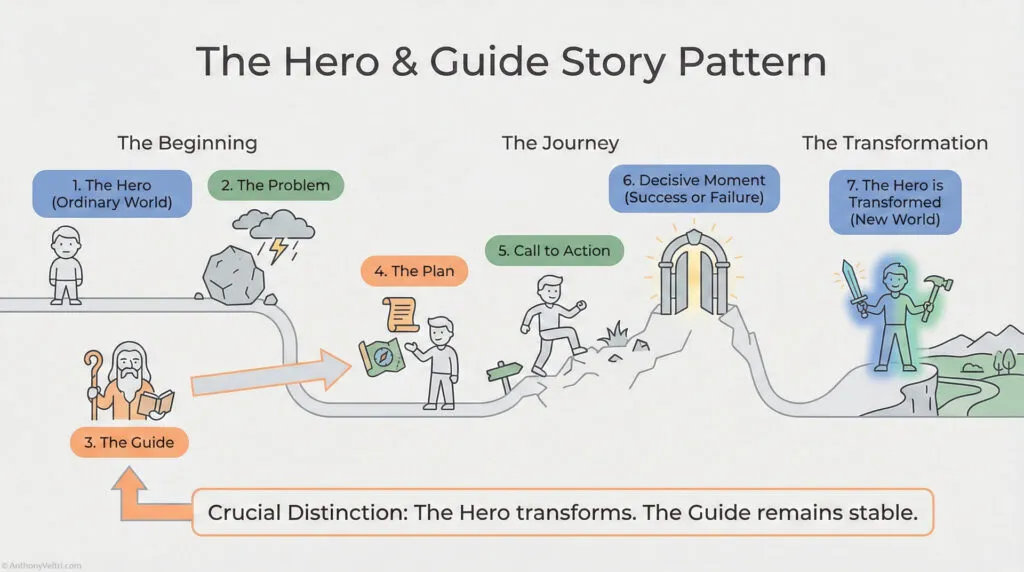

Framework 2: Hero And Guide Story Pattern

The second framework is older than any training course or marketing deck. It is a story pattern that shows up in:

- Ancient myths

- Religious narratives

- Hollywood films

- The stories we tell ourselves about our own lives

Different teachers name it differently. I use a simple version that most executives can memorize in a few minutes.

- A person – the hero

- Has a problem they cannot solve alone

- Meets a guide

- The guide gives them a plan

- The hero is called to action

- The hero faces a decisive moment

- Success or failure

- The hero is transformed*

- * The hero is transformed, but the guide is NOT. This is a critical distinction

You can map almost any blockbuster film to this. You can map many personal stories to it. It sticks in your head not because it is clever, but because humans are wired for story.

For me, the pattern lives in my head as one specific story from childhood. Every time I explain it, I mentally run through that film and its beats. I do not need a script because I am telling a story I already know.

That is the point.

If you are a CEO, an SES, or a program lead who deeply cares about your mission, you can adopt the same pattern. You are not memorizing lines. You are wrapping your real message in a structure your brain already recognizes.

The Big Mistake: Making The Agency The Hero

Here is where governments and businesses consistently go wrong.

They cast themselves as the hero.

- “Our agency did this.”

- “Our program accomplished that.”

- “We are the ones solving the problem.”

There are two problems with this.

First, as humans, we each like to imagine ourselves as the hero of our own story. When we see a message with a pre packaged hero that is not us, we get cognitive friction. There is a small but real “me versus them” reaction.

Second, and more importantly, the hero is not the strongest character in the story.

By definition, the hero starts incomplete. They are missing something at the beginning of the story that they gain along the way. They have to transform.

The strongest character is often the guide.

- The guide does not transform.

- The guide is stable.

- The guide carries knowledge and perspective the hero does not yet have.

- The guide exists to help the hero become who they need to be.

In your work, you want your citizen, your customer, or your internal audience to be the hero.

You want your agency, your program, or your product to play the guide.

None of this is a substitute for actually doing the work. If your program is not delivering real value, no amount of hero and guide framing will fix that. At best it will buy you a short grace period. Everything in this pattern works better when it rests on honest results.

If you insist on playing the hero, two things happen:

- The audience struggles to see themselves in the story.

- You put yourself in a weaker narrative position without realizing it.

When you embrace the guide role, you gain clarity.

Your job becomes:

- Name the problem your hero is facing.

- Show up with empathy and authority.

- Offer a clear plan.

- Call them to action.

- Paint a picture of success and of failure.

- Help them become the kind of person who achieves the outcome.

That is true whether you are scripting a wildfire preparedness video, a cyber hygiene campaign, or a leadership message about culture change.

Combining Motivation And Story

The real magic happens when you start combining these two frameworks.

You can:

- Use the hero and guide pattern to structure your message.

- Use the motivation spectrum and positive/negative motivators to shape the content inside each part.

For example, in the “plan” portion of your story:

- Give the what people a name and definition.

- Give the how people a concrete next step.

- Give the why people a clear reason to care.

- Give the what if people a vision of where this could take them.

When you describe success:

- Tie it to positive accomplishment and affiliation.

- Show what it looks like to be the kind of team or community that did the thing.

When you describe failure:

- Name the real negative outcome without theatrics.

- Use it to highlight why the decision in front of them matters.

This does not require an expensive production. You can do it in an interview. You can do it in a town hall. You can do it in a short on camera message where you are just talking to one person on the other side of the lens.

Who This Is For

Inside government, there is a particular kind of official this works beautifully with.

They are:

- Deeply committed to the mission.

- Frustrated that status quo messages do not change anything.

- Willing to practice and get uncomfortable to become more effective communicators.

- Less concerned with “going along to get along” than with actually moving the needle.

These people are not the majority in any agency. They also tend to have outsized impact over time.

When they get a hold of these frameworks and start practicing:

- They naturally begin weaving motivational framing into their hero stories.

- They start talking about positive and negative outcomes in plain human language.

- Over time, they can do this extemporaneously. They do not need heavy coaching. The pattern becomes part of how they speak.

If you are one of those people, this is an invitation to treat message design as part of your craft, not as a task you bolt on at the end.

Where This Fits With The Other Government Video Work

At this point there are three related pieces in this cluster:

- Field Notes: What I Learned Writing The Government Video Guide

- The origin story and structure of the handbook I wrote for agencies that want to use video responsibly.

- Lessons from disaster response and high risk environments.

- Field Notes: Creating A Safe Beginner Space On Camera

- The pre shoot smartphone ritual and checklist I use to help normal people feel safe and confident on camera.

- How to behave like a guide on set.

- This field note: Motivation And Story Frameworks For Government Leaders

- How to design the actual message so it lands with different kinds of learners.

- How to position your audience as the hero and your agency as the guide.

You can think of it as layers:

- The Government Video Guide is the system and process layer.

- The safe beginner note is the human nervous system layer.

- This note is the story and motivation layer.

You do not have to master all three at once. But when you do, your odds of creating something that actually changes minds and behavior go up dramatically.

How To Start Using This Tomorrow

If you want a simple way to start, try this with your next message, whether it is a video, a briefing, or an all hands email.

- Write down the core of your message in one or two sentences.

- Ask yourself:

- Where am I speaking to “why”

- Where am I speaking to “what”

- Where am I speaking to “how”

- Where am I speaking to “what if”

- Identify the hero and the guide.

- Is the hero my audience, or have I accidentally made my agency the hero

- Add one honest sentence about:

- What happens if people act on this

- What happens if they do not

Then deliver the message and watch how people respond.

You do not need to say “I am using a motivation and hero framework” out loud. You just need to start thinking like a guide who understands how humans actually learn and change. The point is not to remove people’s choices. The point is to give them a clear, honest picture of what is at stake so they can choose with their eyes open.

If you do that consistently, you will not just be someone who “does video” or “gives briefings.” You will be the person who helped your audience cross from where they were to where they needed to go.

Last Updated on December 29, 2025