Field Notes: What The Katrina Book Was Really For

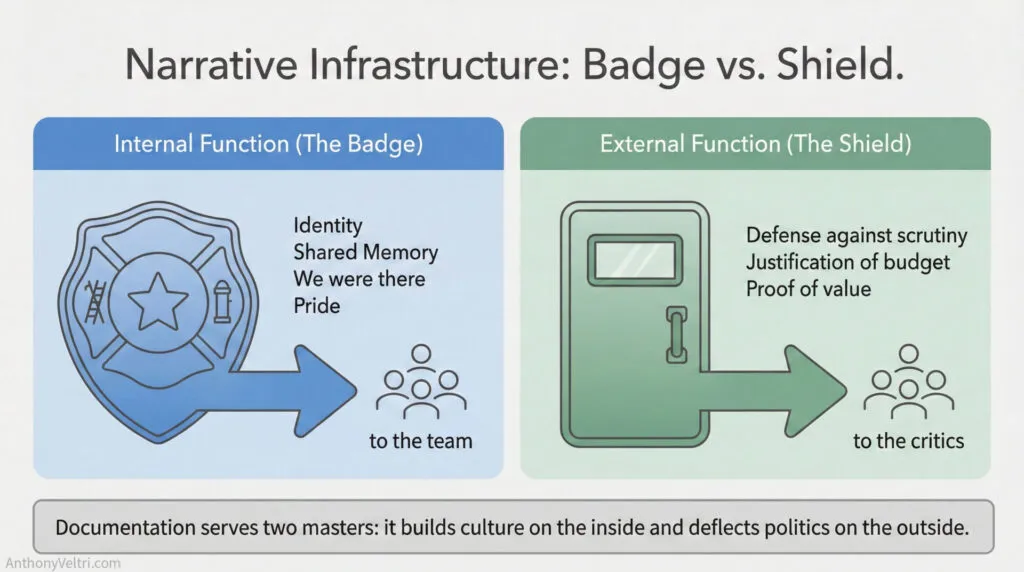

Doctrine Claim: Technical work creates value – narrative work defends it. This field note explains why “doing the job” is not enough if you cannot explain the job to the people who sign the checks. The “Katrina Book” was not a souvenir – it was narrative infrastructure designed to protect the team from political decay.

I did not go to the Gulf Coast to write a book. I went to help.

The book came later, when I realized there was a gap that maps and RF alone could not close. It was not a coffee table project or a vanity piece. It was something closer to narrative infrastructure for a team that had gone a long way from home and then had to justify, to themselves and to others, why it had been the right thing to do.

This is the story behind that book and what it taught me about documentation, politics, and how stories carry risk and legitimacy.

The Quiet Politics Of Mutual Aid

On paper, the system for sending help across state lines is straightforward.

States have mutual aid agreements and memoranda of understanding so that when a disaster hits one region, teams from another region can deploy. For Hurricane Katrina, that meant people and equipment moving long distances under official orders.

In reality, it is never that simple.

When Rhode Island sent a USAR task force to the Gulf Coast, several things were true at the same time:

- The mission was real and needed

- Those same people were also needed back home

- Folks who stayed behind had to cover shifts, worry about risk on their own turf, and answer questions from the public

There is always a background chorus of:

- Who is covering us while you are gone

- What exactly are you doing down there

- Is this really the best use of our best people

The team received a welcome from the governor when they returned, and they deserved it. At the same time, there were quiet questions and second guessing about staffing and priorities that did not match what I had seen on the ground.

That disconnect is where the book really started.

I Was Not Sent There To Write

When I deployed with Rhode Island USAR, my role was technical.

I brought:

- The mobile mapping unit, a self-funded 26-foot box truck I had turned into a GIS and RF lab

- Geospatial capability they did not have in house

- A willingness to plug into whatever gaps they needed filled, inside the limits of my training

They brought:

- A proven task force with their own history, culture, and norms

- A very clear sense of mission

- A level of trust and interdependence that I could feel because they extended it to me

I was documenting the experience because that is how my brain works. I took photos, made notes, tracked where we were and what we were doing.

At some point it clicked:

This is not just for me. This needs to be a record that the team can carry home.

Not because anyone asked me to, but because I could see the shape of the problem they were going to face when they got back.

Scrutiny From Back Home

From the outside, a USAR deployment can look abstract.

People see:

- Crews leaving for a distant disaster

- Overtime lines on a budget

- An empty apparatus bay or familiar faces missing from their usual shifts

What they do not see is:

- The work in the rubble

- The cross-team coordination

- The long days and short nights

- The emotional toll of seeing that much damage up close

When the team came home, they got an official welcome. There were speeches and acknowledgements. That matters.

It did not erase the questions:

- Was sending a Rhode Island task force to the Gulf Coast the right call

- Who paid what price while they were gone

- What exactly did they accomplish down there

Those questions are not evil. They are the natural outcome of a complex system with limited resources. The problem is that the people who actually went are usually too tired and too modest to build their own defense against shallow criticism.

So the risk is real: the work is done, the cost is paid, and the story decays. The next time someone proposes sending a team, the shadow of those questions hangs over the decision.

Deciding To Build A Book Instead Of Just A Folder

I could have given Rhode Island USAR a folder of photos and notes and called it a day.

Instead, the more I watched and listened, the more it felt like the right shape for this record was a book:

- Something physical they could hold, hand to family, or leave in the station

- Something they could send to officials, funders, and skeptics who asked “What did you actually do down there”

- Something that honored the group, not me

So I started to structure what I already had:

- Chronology of the deployment

- Who was there and in what roles

- Where we operated and under what conditions

- Photos that showed people working, not posing

- Context for someone who was not there, so they could follow the story

The goal was never “Anthony writes a book.” The goal was “Rhode Island USAR has a solid, tangible artifact that helps them hold their own narrative.”

In my head, I was not the author so much as the archivist and layout guy.

Learning To Print A Real Book In 2005

There was another timer running in the background.

Rhode Island USAR had a Christmas party coming up in 2005, just a few months after we got home. The idea of having something ready for that event was both terrifying and exactly right.

This was before Kindle, EPUB, and easy print-on-demand. If you wanted a real book, you had to understand things that most people never think about:

- Leading and kerning, so the text is readable at scale

- What a galley is in the publishing sense, not just a ship

- How pages sit in a physical binding, and why the pages near the center need extra space from the spine so you can actually read the inner edge

- The difference between RGB on a screen and CMYK on paper, and how to prepare images and layouts accordingly

I had to learn:

- Adobe InDesign well enough to do real layout work

- How to set margins and gutters so the middle pages did not vanish into the spine

- How to prepare galleys the printer could use

- How to work with color in a way that would survive the press

It was a massive amount of technical production work on top of everything else, but it matched how important the project felt.

The result was that by the time the Christmas party came around, there were galleys in people’s hands. Not a vague promise of “one day we will have a book,” but actual printed pages they could touch, flip through, and recognize themselves in.

That moment mattered to me. It meant:

- The story did not disappear into my hard drive

- The team saw that their work was important enough to justify a real artifact, not a quick Word report

- All the invisible skills, from GIS and RF to layout and color, came together in service of something simple and human: “We were there.”

What The Book Did For The Team

The book gave the task force several practical things.

1. A shared memory that was not just in their heads

After a deployment, memories scatter. People remember different details, and over time individual stories drift.

By putting it into a single artifact, the team had:

- A reference they could all point to

- A way to bring newer members into “this is part of who we are as a unit”

- A way to remember not just the highlights but the grind

2. A response to “Was this worth it”

When someone asks “Was it worth sending you all the way down there” you can answer in person. That works once or twice.

A book lets you answer that question hundreds of times without reliving the whole thing:

- Hand it to the person asking

- Let them see for themselves the scale of the work and the conditions

- Let them notice things they would never pick up from a two minute conversation

It does not end all criticism, but it changes the footing. You are no longer defending yourself with vague phrases. You are pointing to evidence.

3. A way to honor the reality, not the Hollywood version

Disaster work is often flattened in public imagination into extremes: either hero worship or failure.

The book could show:

- The boring parts that are still essential

- The small acts of competence that never make the news

- The team eating in strange places, fixing vehicles, solving problems that seem mundane until you realize the context

In other words, it could show the work as it is, which is the most respectful way to treat it.

How It Changed Me

From the outside, the Katrina book might look like a side project. To me, it was the start of a pattern I have repeated in other domains.

A few things it taught me.

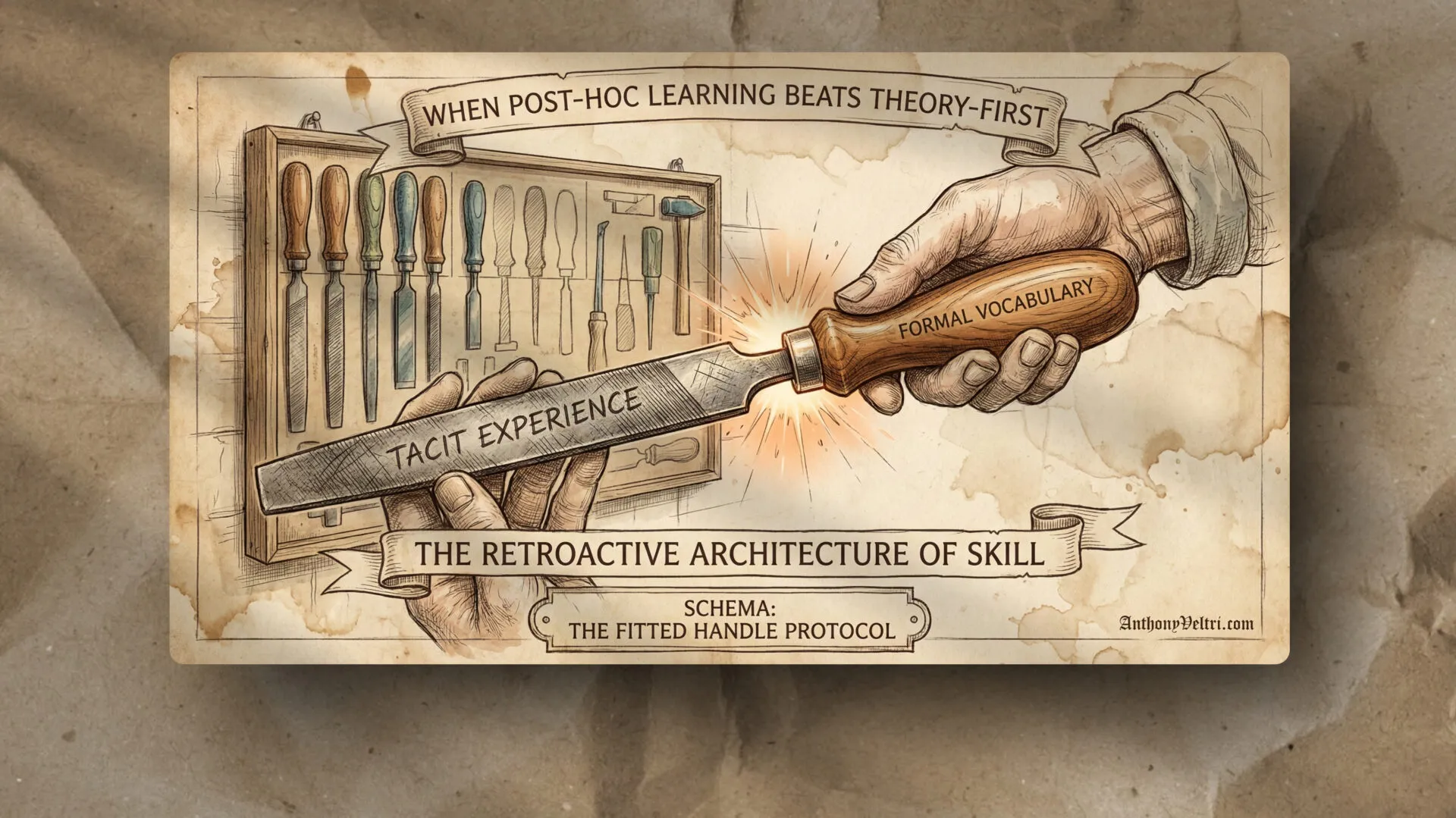

1. Technical systems alone are not enough

The mobile mapping unit, the RF lab, the WiMAX backhaul, the VoIP routing. All of that mattered.

None of it answered:

- “Who were we out there”

- “What did we actually do”

- “How do we explain this to people who were not there”

The book taught me that:

You can build technical infrastructure and narrative infrastructure in parallel, and both are required if you want the work to survive politically and culturally.

Later, the Government Video Guide and my testimonial frameworks are very much in that same family.

2. Documentation can be a form of care

Writing the book was not neutral. It was a way of saying:

- Your effort matters enough to record

- Your story should not be left to someone who was not there

- You deserve to be able to show your kids and colleagues what you did

It is easy to treat documentation as a chore. In this case, it was almost pastoral. It was an act of care toward a team that had made room for me in their orbit.

3. I have a habit of building the missing system without being asked

No one assigned me “write a book about this deployment.” There was no line item for it.

I saw the gap between:

- The reality of the deployment

- The scrutiny and questions waiting back home

Then I did what I tend to do:

- Sketched a structure (a book)

- Filled it with the right content

- Learned how to lay it out, prepare galleys, and get it printed in time for the 2005 Christmas party

- Handed it back to the people who actually owned the story

Sometimes this habit has hurt me, when I build systems for people who cannot or will not care for them.

In this case, it felt right.

What The Katrina Book Was Really For

If I strip the whole thing down to one sentence, the Katrina book was for this:

So that when someone in Rhode Island wondered whether sending that team to the Gulf Coast had been a good idea, there was more than a shrug or a sound bite to answer them.

It was for:

- The firefighters and medics who went

- The staff who stayed behind and covered

- The families who had someone gone for that stretch of time

- The future decision makers who might need evidence that mutual aid is not just an abstract policy

It was not primarily for the public. It was not for the news cycle. It was not really even for me.

It was infrastructure. Narrative infrastructure.

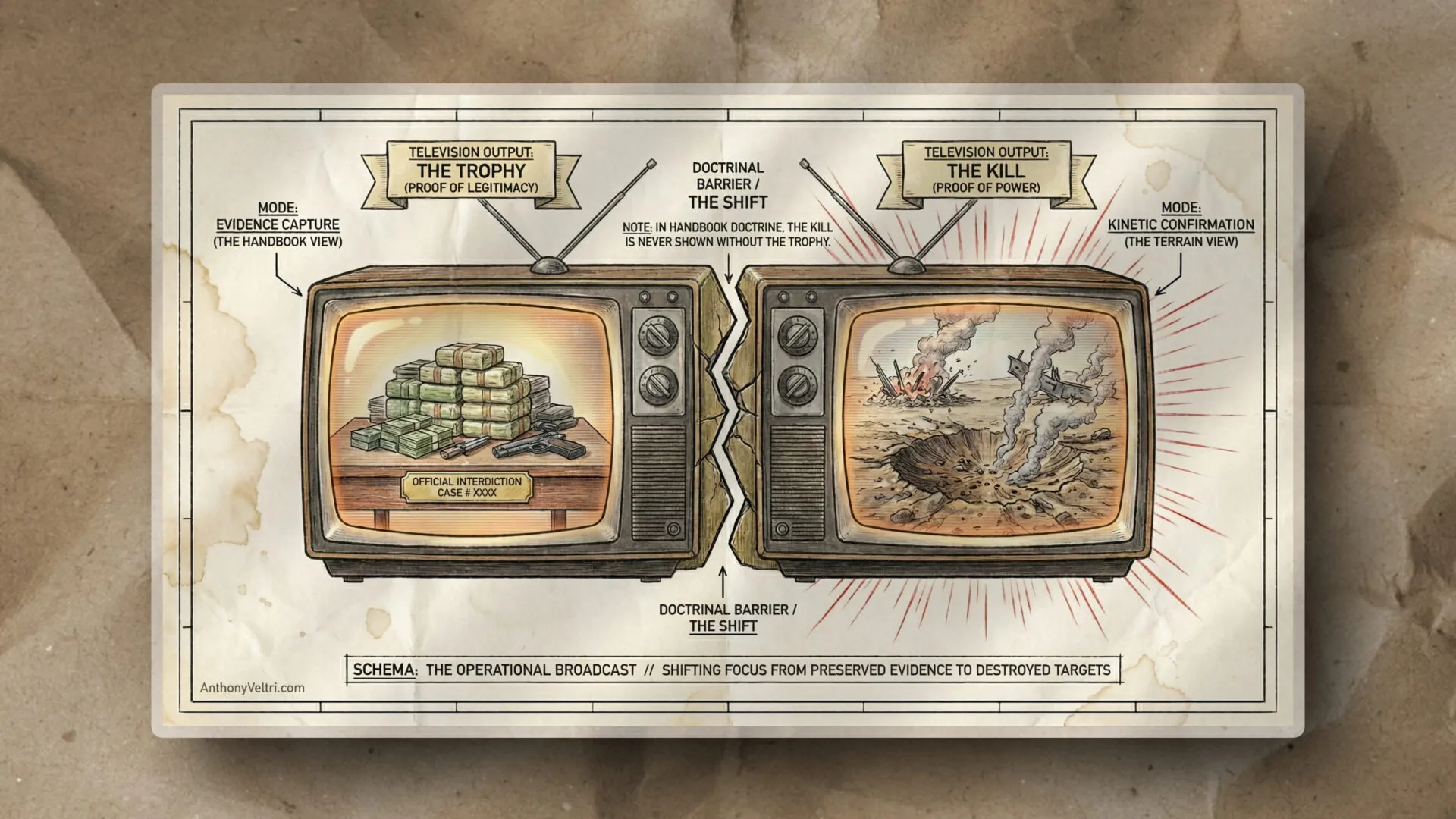

Badge and shield

This guide explains why this work of narrative presentation and shaping serves two purposes

Badge: What this work meant on the inside. How it felt to the team, what it signaled about who they were, and why they were proud of it. & Shield: What this work defended on the outside. The scrutiny, risk, or doubt it absorbed so that the team could keep doing the mission without having to fight the same battles over and over.

Badge: For the Rhode Island USAR team, this book became a visible record of what they actually did on the Gulf Coast, not just another certificate on the wall.

Shield: For state leadership and skeptical stakeholders, it became evidence that deploying the team was the right call and that their time away from home had measurable impact.

How This Connects To My Later Work

When I look at the Katrina book now, I see the early shape of things I do today:

- Documenting systems so they can be defended in budget meetings

- Building guides and frameworks so others can tell their story well

- Treating video and writing as part of the system, not as decoration

The Government Video Guide, the Video Testimonial Guide, and the doctrine I am writing now all sit on the same foundation:

- People do important work

- That work is fragile if it only lives in their heads or in technical logs

- Someone needs to build the narrative structures that let them show what they did, why it mattered, and how to decide wisely next time

The Katrina book was the first time I did that at scale for a team in crisis.

I am still learning how to do it in ways that do not grind me down. I am not done with that part of the story.

But I am glad that book exists, and that the people who went to the Gulf Coast have something to point to that says, very simply, “We were there.”

Last Updated on December 7, 2025