Flying The Picture: What A Little Cessna Taught Me About Mission Systems

The legal limit is not the survival limit.

A flight plan can be legal but operationally suicidal. This briefing uses a “No-Go” decision from a Naval Aviator to explain the Compliance Trap in digital architecture. If you design your system to operate at 99% of its capacity, you are compliant (but you are also one gust of wind away from a crash). Better to be late on the ground than wrong in the air.

There is a joke among pilots.

“How can you tell if someone is a US naval aviator

Do not worry. They will tell you.”

In my case, I am not a naval aviator.

I am the other guy in that story. The one who went to flight school because his day job in infrastructure protection and airborne collection was giving him a picture that did not feel complete.

Why I Went To Flight School At All

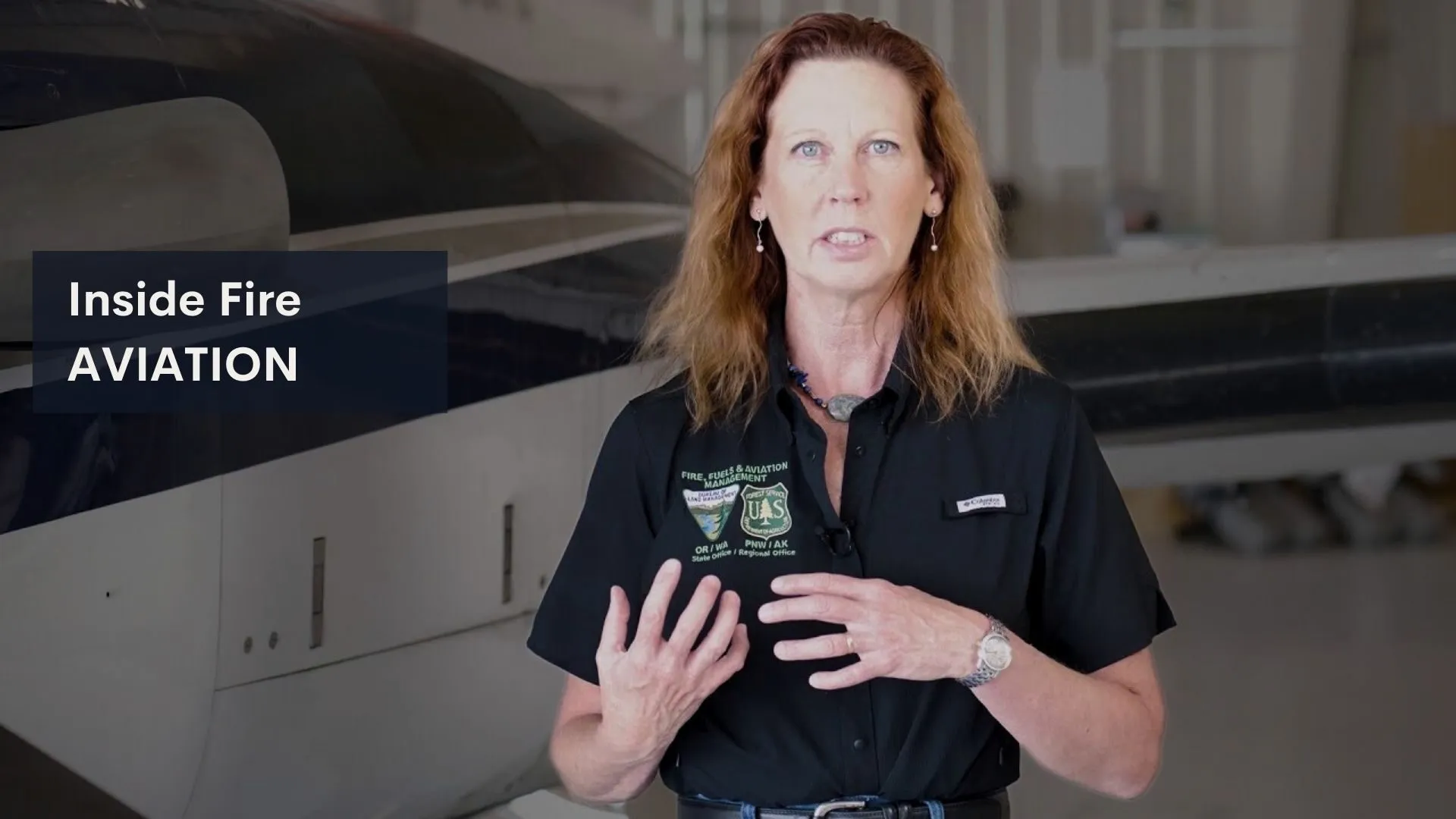

At the time, I was working for DHS on programs that depended heavily on airborne collection.

Sensors on platforms. Imagery. Flights through complicated airspace.

On paper, it sounded straightforward.

- Task the aircraft

- Gather the data

- Push it into the system

In the meeting room, the questions were straightforward enough.

- “Why can we not just fly today”

- “Why is this area not covered yet”

- “It is 2010, are we really still limited by weather”

I knew enough to repeat the stock answers about safety and constraints. I did not feel them in my bones.

So when an opportunity appeared to train at Dulles Aviation in Manassas, Virginia, I took it.

The US Marine Corps was contracting part of their initial flight training there. I joined in on that train, did the work, and continued beyond the twenty four hours they required. Eventually I earned my private pilot license.

On paper, that is a hobby.

In reality, it rewired how I think about mission systems that depend on anything in the sky.

The Flight Plan That Looked Fine On Paper

To finish your private pilot license, you need to complete a multi leg cross country flight.

I had one planned from Dulles Aviation. It was a common route the school used.

If you know Washington DC airspace, you know that you live inside a bowl of rules.

- SFRA

- ADIZ

- Restricted areas

- Prohibited zones you do not want to blunder into by mistake

On the sectional chart, the route was legal. The lines went around what needed to be avoided. It was tight, but tight in the way a lot of entry level cross country routes are.

A friend of mine from high school was also getting his license. Another friend from the same circle had gone a different way. He is a naval aviator. Rotor wing. A hotshot by any measure. He flew with a unit whose alumni include astronauts and some of the best helicopter pilots on Earth.

When someone asked if he was going to follow the astronaut path after announcing his assignment to the new unit, he answered:

“I prefer to keep my flying between zero and fifty feet AGL.”

He looked at the cross-country flight plan that the school had blessed.

He did not try to impress anyone.

He just shook his head.

“Nope. I would not do this at all. This is bounded by too much airspace you do not want to be close to. All it takes is one inattentive moment in turbulence and now you are having a conversation you do not want to have.”

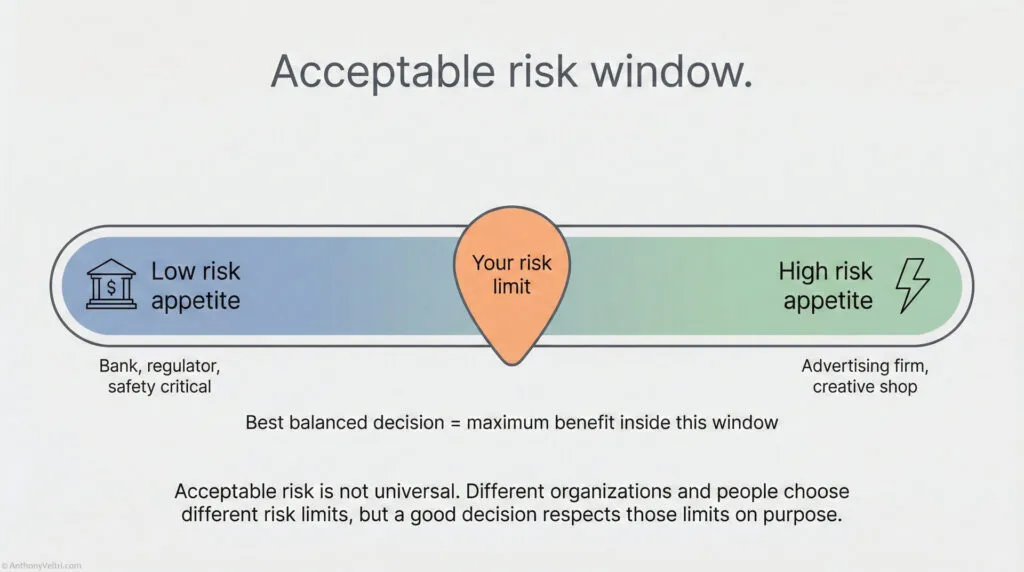

The flight was technically correct.

From his perspective, it was operationally brittle.

That was one of my first real lessons in the difference between:

- “Legally allowable”

- “Operationally wise in the real sky with stress and wind and distractions”

Feeling The Wind In A Cessna 172

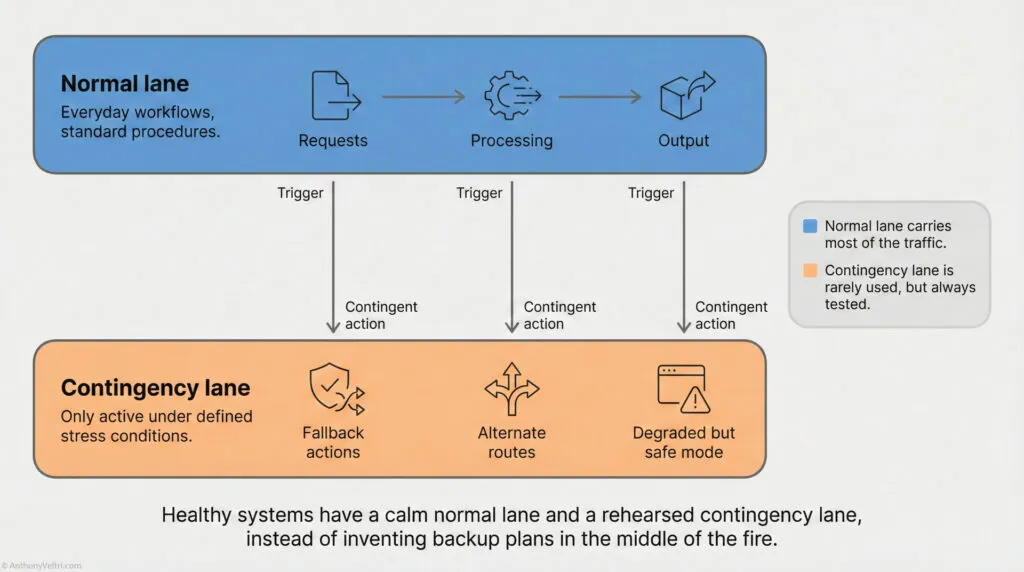

Architectural Slack: Designing for the “Legal Limit” creates a Single Lane system. Respecting the envelope means building a “Contingency Lane” (Orange) so you have space to maneuver when the weather turns. Shifting Lanes: When the air turns against you, you leave the “Normal Lane” (Efficiency) and enter the “Contingency Lane” (Survival). You cannot fly a “Blue Lane” mission in “Orange Lane” weather.

Flight training also adjusted my attitude toward “just fly the mission.”

It is easy, as an executive or architect, to talk as if the air is a static medium.

In the cockpit of a Cessna 172 on a gusty day, you learn quickly that it is not.

You feel the thermals, the chop, the subtle shifts that make the workload spike. You learn to read the horizon and your own stomach at the same time.

You learn how much attention it takes just to:

- Hold an altitude

- Maintain heading

- Keep track of checklists and radios

You also learn how narrow your mental bandwidth becomes when the air turns against you.

After those flights, hearing “we cannot fly today” or “the data will not be very good if we do” landed differently.

I no longer heard an excuse.

I heard a pilot or crew quietly saying:

- The risk envelope is wrong today

- The data quality will not justify the exposure

- The sky is in charge, not us

Once you have been thrown around enough by wind in a small aircraft, you stop treating air assets as simple push button services and start treating them as living, constrained systems.

The Checkride I Am Glad I Failed

I did not pass my checkride the first time.

It was a windy day. I had passed every part of the profile up to that point. Steep turns. Slow flight. Stalls. Navigation. Radio work.

On the way back, the examiner pulled the throttle and said, “Engine out.”

It is a maneuver you practice. You pick a field. You manage glide. You work the checklist and talk through your options.

I would have landed long.

We both knew it.

It was not a smoking crater scenario. But it was not good enough to sign a certificate that says “this person can handle this for real.”

Everything else on that ride was fine. That one maneuver was not.

So I failed.

It stung. It meant re scheduling. More time. More money.

It also exposed something far more important than a bruised ego.

I had treated the emergency procedures as one more item on the list. The examiner treated them as the line between “safe enough to be trusted with lives” and “not yet.”

I am grateful he did.

I went back to my CFI and focused almost entirely on emergency work.

- Engine out

- Glide planning under stress

- Abnormals and “what if” drills

Not because the FAA wanted more boxes checked, but because I did not want a weak link hiding inside my own skill stack.

That experience permanently colored how I look at any system that uses checkrides, task books or certifications.

If a task book is just a formality, you have a compliance culture.

If a task book can stop you from advancing until you are really ready, you have the beginnings of a safety culture.

I am very glad my first checkride examiner refused to sign my task book that day.

Why This Matters For Mission Systems

On the surface, this is just a story about flight training.

In reality, it changed how I approach any system where airborne platforms and ground systems have to work together.

It taught me to ask different questions.

Instead of:

- “Why did you not fly”

I ask:

- “What did you see in the weather picture that made this a bad idea”

- “What risk are you protecting us from today”

- “If we insist on flying anyway, what quality profile should we expect from the data”

Instead of assuming that:

- More sorties always equals more value

I learned to think about:

- Meaningful collection windows

- Fatigue, workload and how much bandwidth operators really have

- The difference between what the system diagram says and what the crew lives

It also made me a better translator.

When air crews talk about turbulence, crosswinds, icing, minima, duty days and maintenance, I do not hear “technical noise.”

I hear constraints that should shape:

- How we plan collection

- How we fuse data

- How we talk to leaders about what is realistic

In other words, it helped me connect the air picture to the decision picture in a way that respects both.

How This Connects To Doctrine

Through the doctrine lens, this experience sits at the intersection of several principles.

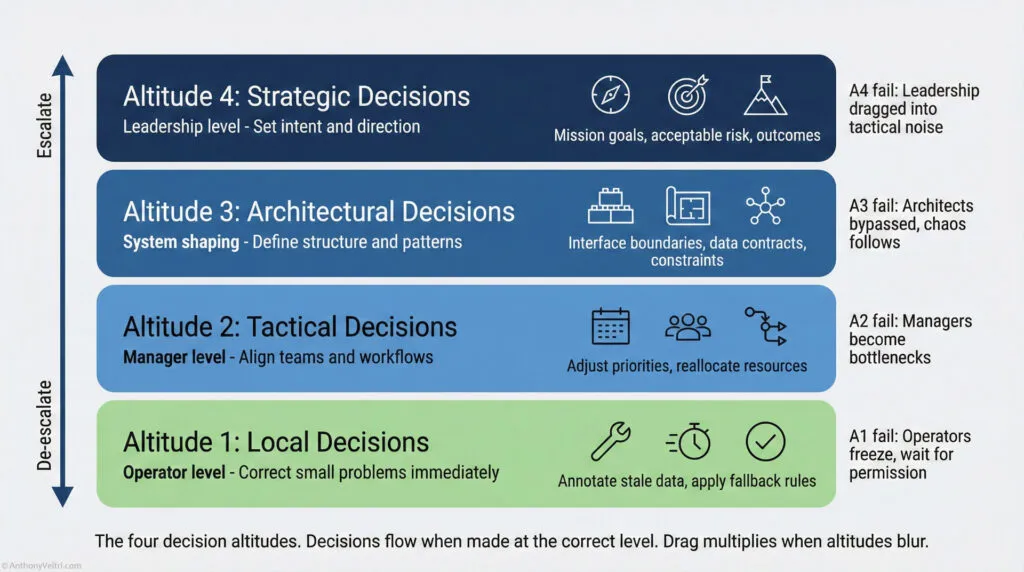

- Decision altitudes.

There are things you can see from the cockpit that an executive cannot see from a map, and vice versa. Respecting both altitudes matters. - Useful interoperability, not perfect interoperability.

Airborne collection does not always produce the perfect dataset the slide deck wants. The question is whether what you can fly today is useful, not perfect. - Commitment outperforms compliance.

A pilot who says “we are not flying today” when the pressure is on is not being difficult. They are protecting the mission and the people. That is commitment, not non compliance. The same is true of an examiner who refuses to sign a checkride when an emergency maneuver is not ready. - Human as interface detector.

If the only person who can translate between air crews and analysts is someone who has lived both worlds, that is a sign the organization needs better interfaces, not just a hero with earplugs and a headset.

It also shaped how I show up in rooms where air assets are just lines on a PowerPoint.

I am the person who will say:

- “Here is what this flight plan feels like from the cockpit”

- “Here is what this weather profile does to your collection plan”

- “Here is why that path looks legal but is not a good idea in real air”

Not because I know better than the pilots, but because I have just enough skin in that game to respect what they are telling us.

Why It Matters For High Tempo Air Networks

In high-tempo air networks, whether they are national or allied, the technology stack is easy to romanticize.

Radars, links, tracks, data fusing engines.

What does not show up as clearly on the diagram is:

- The human workload in the cockpit and the crew room

- The reality that sometimes the right answer is “not today”

- The need for people in technical leadership who understand that aviation is not a service you dial up, but a discipline that lives within physics and risk

That short stretch of time at Dulles Aviation did not make me a tactical expert.

It did something more modest and more useful.

It inoculated me against treating airborne collection as a magic tap you just turn on.

It taught me to trust crews when they say no.

And it gave me one more lens to connect the sky, the sensors, and the system picture in an honest way.

If you work in any world that depends on what happens between zero and fifty thousand feet, it is worth asking yourself:

- Who in this room actually knows what the air feels like

- And are we letting that reality shape our doctrine, or just our excuses

That is the gap I try to stand in. Not as an aviator telling war stories, but as a technologist who has spent enough hours in a small plane to know that the sky always gets a vote, sometimes several.

Last Updated on February 7, 2026