Gates That Matter: Task Books, Checkrides And Real Safety

There are only two kinds of gates in a system:

- The ones everyone passes

- The ones where “no” is a real option

The first kind produces compliance.

The second kind produces safety.

I learned that two different ways.

When The Task Book Actually Means Something

In wildland fire, the task book is more than a form.

If you want to be:

- A Sawyer

- A firefighter type 1

- A crew boss

- A dispatcher or Incident Commander

you carry a task book.

The book lists real tasks you must perform under real conditions. Not just once, but enough times that qualified people are willing to sign their names next to yours.

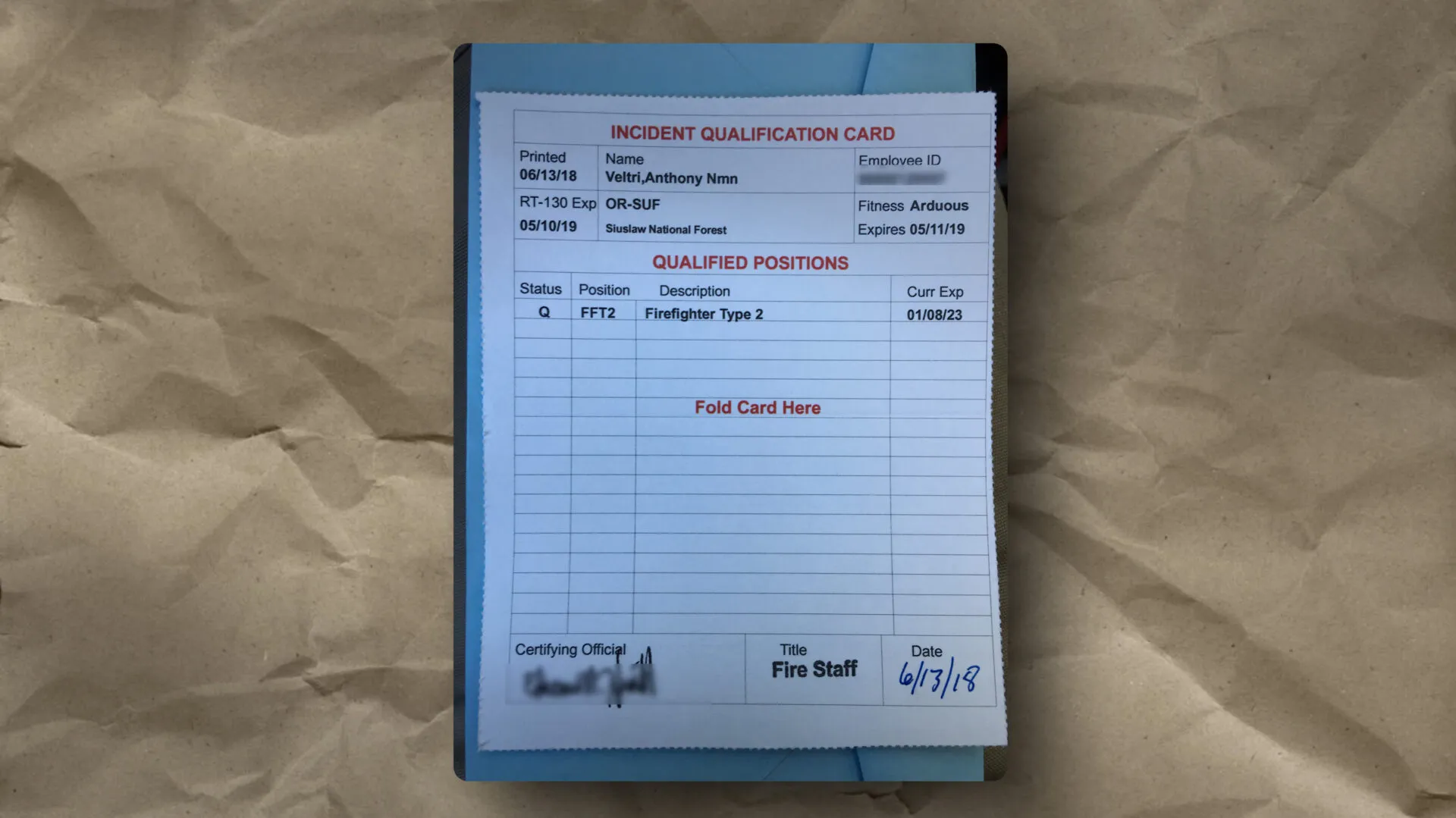

In wildland fire, taking the course is only the first step. You can sit through S classes, collect certificates, and carry an open taskbook in your line pack, but none of that makes you qualified. Until a certifying official has watched you do the job, signed the taskbook, and accepted responsibility for your performance, you are still a trainee. The red card is brutally honest about that. It does not list your potential or your coursework. It only lists the positions where someone with authority has been willing to put their name on the line and say, “This person can carry this level of responsibility and keep people safe.”

When someone signs off your task book, they are saying:

- “I have seen this person do this for real”

- “I am willing to stake my reputation on their readiness”

On incident, that matters.

When you hand over command from one IC to another at the end of an operational period, the system is trusting that task book. You can swap people across agencies because the gate meant something.

If the task book were just a training attendance sheet, the whole Incident Command System would be a lie.

The Checkride I Am Glad I Failed

My flight training gave me the same lesson from a different angle.

On my first checkride for my private pilot license, I passed every part of the profile.

- Steep turns

- Slow flight

- Stalls

- Navigation

- Radio work

On the way back, the examiner pulled the throttle.

“Engine out.”

It was a maneuver I had practiced. I picked a field. I worked the checklist. I set up the glide.

I would have landed long.

It was not a catastrophe scenario, but it was not good enough to certify me to handle that for real.

Everything else on that ride was fine. That one maneuver was not.

So I failed.

It hurt. It cost time and money. It also did exactly what a safety gate should do.

It forced me to admit that I had treated emergency procedures like another line item.

The examiner had not.

He treated that maneuver as the line between:

- “Safe enough to carry people”

- “Not yet”

I went back to my instructor and focused almost entirely on emergency work.

The second checkride went very differently.

More important than the pass was the mindset change:

- I stopped assuming that passing a gate was inevitable

- I started viewing every signature as a serious claim

Safety Culture vs Compliance Culture

In a compliance culture:

- Gates exist to document that training was offered

- Failing someone is rare and socially awkward

- People treat signatures as “I was there”

In a safety culture:

- Gates protect people who are not in the room

- Failing someone is painful but acceptable

- People treat signatures as “I stand behind this person”

Wildland fire task books and honest checkrides are small but powerful examples of a safety culture.

They slow people down in training so that reality does not slow them down in a body bag report.

Why This Matters For Mission Systems And Air Networks

For mission systems, including air networks, the same idea applies to:

- System certifications

- Role qualifications

- Data and interface approvals

You can either:

- Rubber stamp them to keep projects moving

- Or let “no” be a real answer until things are actually ready

The doctrine for me is:

- Use as few gates as possible

- Make the ones you keep matter

- Accept the cost of “not yet” when a gate is not honestly passed

That is what keeps pilots, crews, controllers and end users alive when your systems touch the real world.

Last Updated on November 26, 2025