Golden Datasets: The Tracks Everyone Trusts

High tempo systems live or die on one simple question:

“Which data do we treat as the truth when opinions differ?”

If everyone has their own private truth, you do not have a system. You have a debate club with better screens.

In my world, that has shown up as:

- Fire perimeters

- Critical infrastructure layers

- Federal Register notices

- Sensor feeds and operational layers in systems like iCAV

In an air picture context, it shows up as tracks. Which track is authoritative when different sensors disagree.

I call these golden datasets.

They are the sources of meaning that other systems and decisions depend on.

Not All Data Is Equal

When I worked on national geospatial viewers, we had many overlapping layers:

- Power plants

- Pipelines

- Transportation networks

- Protective buffers

- Incident footprints

For some questions, any reasonable dataset would do.

For others, it mattered a lot which dataset we treated as authoritative:

- “Is this facility officially designated critical infrastructure”

- “Which fire perimeter is the one we brief to senior leaders”

You do not want five different answers.

So we made explicit decisions:

- For this question, this dataset is golden

- It has a named steward

- There are rules for how and when it can change

- Other feeds can decorate it, but not contradict it silently

It is the same logic as a radar track of record. You can fuse and correlate, but at the end of the day you need a single representation that the system and humans will treat as “the” object.

Proudly Maintained By

The Hoover Dam turbine plate that reads “Proudly Maintained By Mike E.” is what a golden dataset should feel like.

It is not just technically correct.

It has:

- A name

- A steward

- A sense that someone has their hands and reputation on it

If nobody would be proud to put their name on a dataset, you should be very cautious about making it golden.

A golden dataset is not just “the table in the database that has the most fields.” It is the dataset that:

- People rely on under stress

- Someone owns emotionally and technically

- Has clear rules for update, correction and caveats

How Golden Datasets Work In Practice

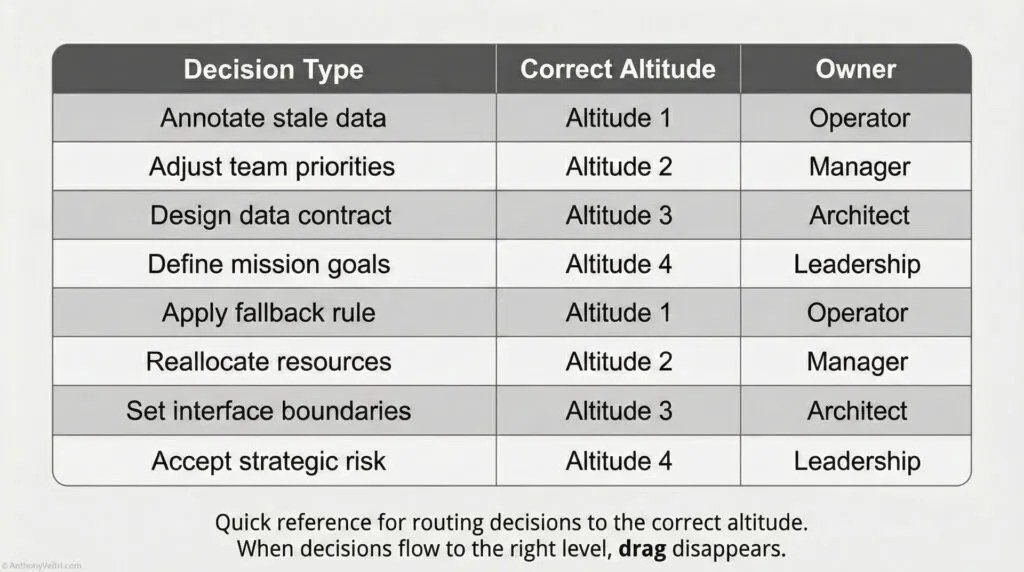

In practice, I treat golden datasets like this:

- Define the question.

“For what decision is this dataset golden”

Not “in general,” but “for this mission.” - Name the steward.

A person or tightly defined role, not “the data team.” - Document the contract.

- What fields are authoritative

- What is the cadence of update

- What caveats apply

- Expose freshness and limits.

A golden dataset can still be stale or incomplete. The difference is that you admit it. - Protect the interface.

Clients can add context. They do not silently fork the truth.

In iCAV, this meant clear ownership of critical infrastructure datasets and clear rules about how we ingested partner feeds around them. In wildfire, it meant respecting one perimeter as the briefing perimeter, even while other experimental or local products existed.

Why This Matters For Air Pictures

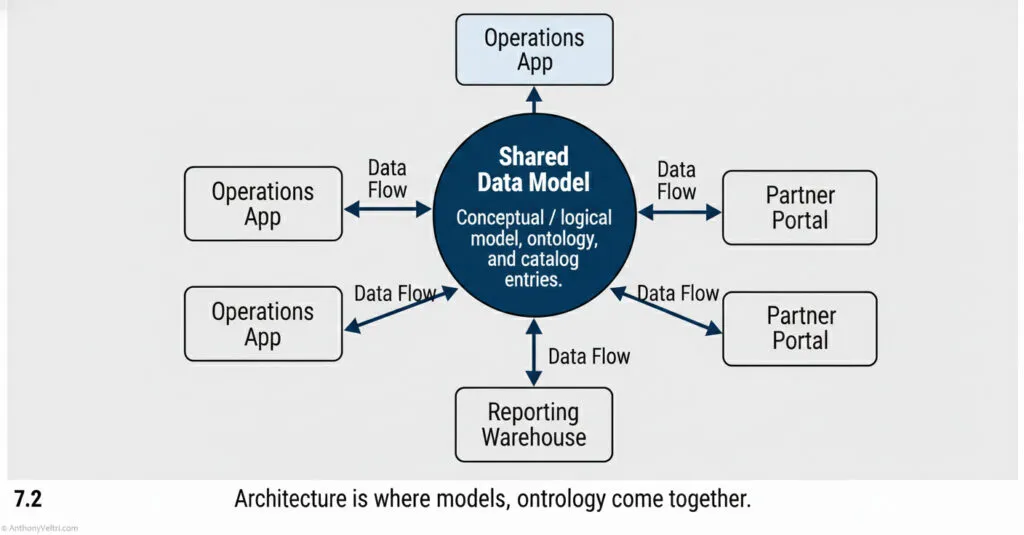

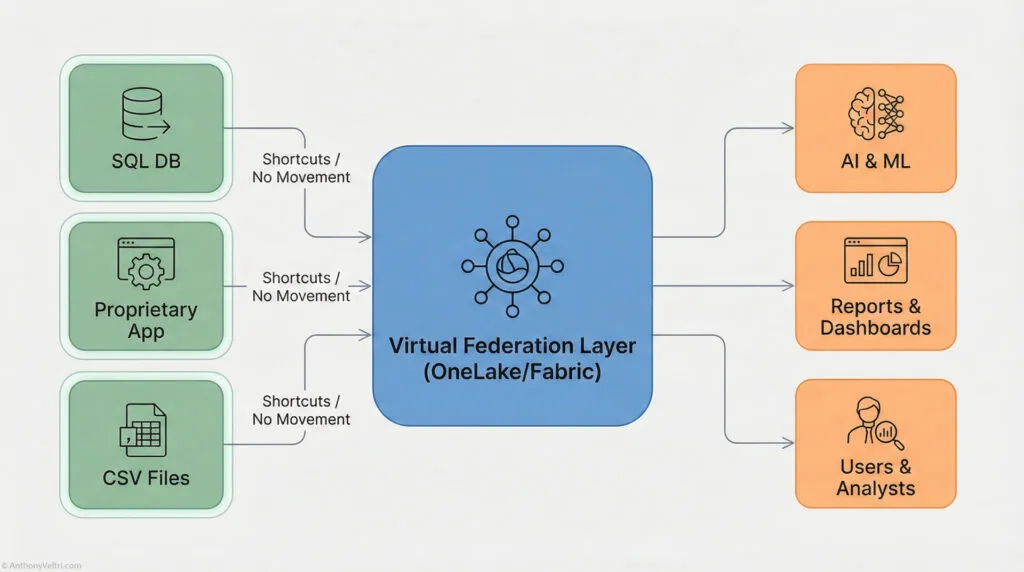

Golden Views over Federated Data: You don’t need to copy every sensor feed. You can build a “Virtual Federation Layer” (Center) that acts as the Golden View for the user, while the raw data stays where it is.

Translate this to an air network and you get:

- Golden tracks of record

- Golden identification statuses

- Golden reference grids and airspace definitions

You might have many contributing sensors and many consumer systems. You can only have a limited number of golden sources per question if you want coherence.

The doctrine point is simple:

“Treat key datasets like Hoover Dam turbines. Someone should be proud enough to rivet their name to them.”

Everything else can be derivative.

Last Updated on December 9, 2025