Guarding the Room: A Hubbard Brook Story About Science and Funding

Know What Room You Are In: A Lesson From Hubbard Brook

Note:

This is one vignette from the 60th anniversary of the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest in 2015. Names and technical details are simplified to keep the focus on the pattern.

“I’m going to pull a trick on you,” I told her. “You’ll know it’s coming, but I want you to see what happens anyway.”

We were driving to the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest in fall 2015. She was a senior scientist stepping into a principal leadership role at one of the longest-running ecological research sites in North America. A big funding meeting was coming up, and she’d have maybe one real window to make her pitch.

I was there to help capture the site’s 60th anniversary on video. But first, we had to drive there, and during that drive she’d asked what I would do to prepare for that meeting. So we ran a quick simulation to see if we could catch that blind spot in action..

1. Context: Hubbard Brook at 60

Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest is one of those rare places where long-term science actually happens. Decades of data. Generations of scientists. A living record of how forests, water, and atmosphere interact.

Around 2015, for the 60th anniversary, I was invited to come up and help with video documentation and scientist communications. The scientist who picked me up was not a grad student or a junior hire.

She was stepping into a role that had once been held by a heavyweight like Dr. Gene Likens, one of the founders of the program at Hubbard Brook and an internationally renowned researcher. In a very real sense, she was part of that same lineage and pedigree, taking over a role that giants had built.

It was fall in New Hampshire. Not yet winter, but you could feel it coming.

One conversation on the drive up became a pattern I have used ever since.

2. The Car Ride: “Science Speaks for Itself” (It Does Not)

On the ride up, she told me about one of many Hubbard Brook research efforts:

- Using oxygen isotopes to age date groundwater and related processes.

- The significance of that work for understanding the system.

- How funding for Hubbard Brook and similar work was tight.

- A big meeting coming up with important funders and decision makers.

Somewhere between her office and the forest, we hit a familiar idea:

“We often assume the science speaks for itself.”

I pushed back.

“Science is mute. It does not speak for itself at all.

People like you speak for it. Stories speak for it. You still need to make the case.”

She asked what I meant.

So I told her I was going to show her, in real time, how this plays out.

3. The Setup: One Neutral Funder, One Shot

We talked through the upcoming meeting.

- There would be funders and senior people in the room.

- Some might be skeptical.

- Time would be limited.

- She would probably have one real shot to make her case before attention drifted.

I asked:

“Give me an example of someone who is not hostile, but not a cheerleader either.

Someone neutral. Curious. Maybe a little skeptical.”

She gave me a composite version of that person.

I said:

“Okay. I am going to play that person.

You make your pitch the way you normally would.

We both know I am going to pull a trick on you.

But I want you to see what happens anyway.”

She agreed.

We were still just driving up the highway.

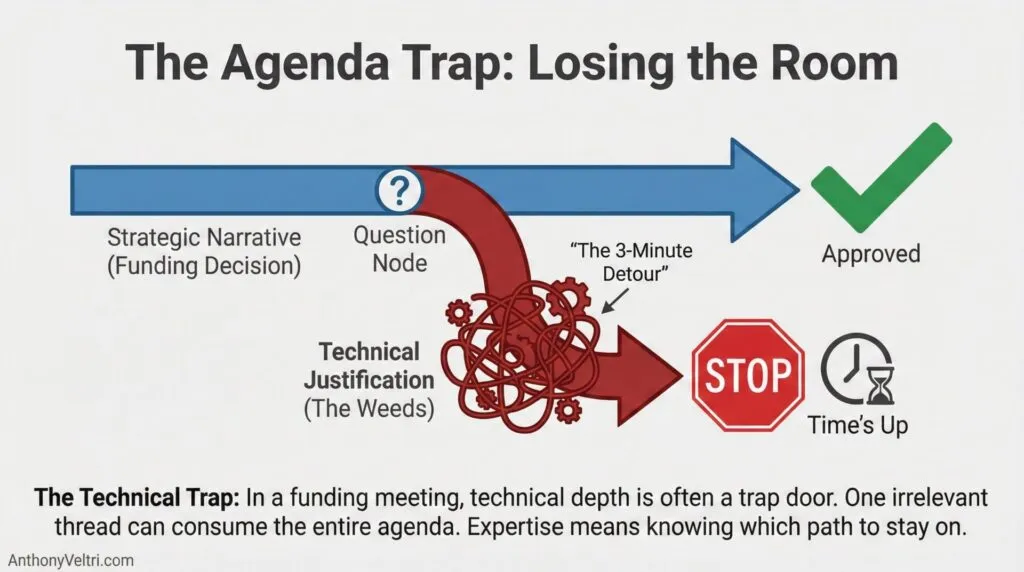

4. The Pitch and the Trap: Oxygen Isotopes as Bait

She started her pitch:

- Why the research matters.

- How Hubbard Brook’s long-term data is unique.

- What insights could be unlocked with this funding.

- What was at stake if the work stopped.

She did a good job. It was clear and earnest.

Then she wrapped up:

“So that is why this is important work for us and for Hubbard Brook.

I would be happy to answer any questions.”

Now it was my turn.

I raised my hand, in character as the neutral but not easy funder:

“Yes, I have a question.

How did you choose that particular oxygen isotope for your analysis?”

She knew a trick was coming. We had literally just discussed that.

But she is a scientist. And scientists are trained to answer questions.

So she answered.

- Why that isotope was the right baseline.

- How it compared to other choices.

- The rationale, the methodology, the validation.

She was thoughtful, confident, and completely in her element.

Two or three minutes went by.

Then I said:

“Time.

That is the meeting. That is your shot. What happened?”

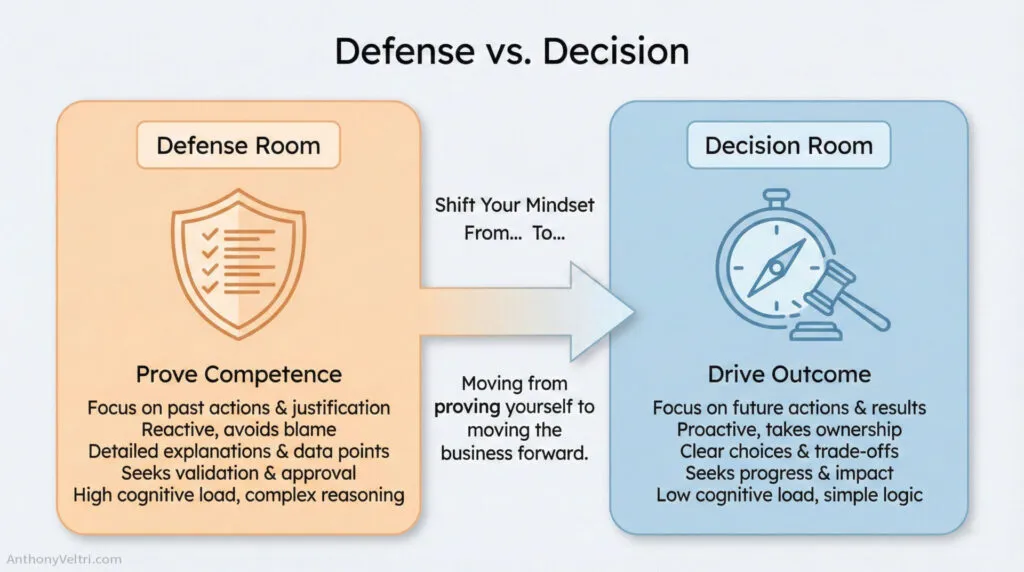

5. The Diagnosis: Defense Conditioning

We pulled apart what had just happened.

She already knew the answer:

- We had talked about how little time she would have with these funders.

- We had agreed she needed to guard that time fiercely.

- I told her I would hypnotize her with a technical question, and she still walked straight into it.

Not because she was careless or naive.

And certainly not because she was unqualified. This was someone picking up the same kind of responsibility that a giant like Likens once carried. The point was not to shame her (we were laughing about the “trick” the whole time). It was to show that even people with that level of pedigree and training are vulnerable to the same trap. But they could learn to identify and avoid that trap as well.

She answered the question because she respects the data. In a scientific review, that integrity is her shield. I just had to show her that in a funding room, that same integrity could be used as a weapon against her time.

From the first committee meeting to the final PhD dissertation defense, we are conditioned:

- A question is a test of competence.

- You prove your worth by answering it thoroughly.

- The more technical the question, the more your brain lights up:

“Finally, something in my lane. Let me show them I know what I am doing.”

That reflex is valuable in:

- Peer review.

- Technical conferences.

- Defense rooms.

In a funding or decision meeting, that same reflex becomes a liability.

One irrelevant technical question can hijack your only window

to talk about what actually matters.

Why the work should continue and what it enables.

The question about oxygen isotopes was not malicious.

It was just off mission for that meeting.

6. The Fix: Detect and Defer

We started talking about what to do differently.

The goal was not to make her hostile or evasive.

The goal was to give her a third option between:

- Oversharing technical detail, and

- Stonewalling.

We came up with a pattern.

6.1 Detect the bait

Ask yourself, silently:

- Is this question central to the decision in this room?

- Or is it interesting but tangential?

If it is central, answer it clearly and briefly.

If it is tangential, you need to park it.

6.2 Defer with respect

We practiced language like:

“That is a great technical question, and there is a lot to unpack there.

I would love to dig into it with you after this meeting.

For now, I would like to keep us focused on the funding decision and what it unlocks.”

Or:

“Short answer, we chose that isotope because it is the standard for this kind of analysis.

I can walk you through the references and calibration later if you would like,

but I do not want to use our limited time here on lab details.”

The structure is always:

- Acknowledge the question.

- Give a one sentence answer if needed.

- Redirect to the purpose of the meeting.

- Offer a follow up channel (side conversation, email, later session).

You are not dodging. You are guarding the room.

In hindsight: What struck me wasn’t that she fell for the trap… everyone does. It was how quickly she pivoted. She didn’t get defensive or make excuses. She immediately dissected the mechanic so she could use it. That is the mark of a true Principal Investigator.

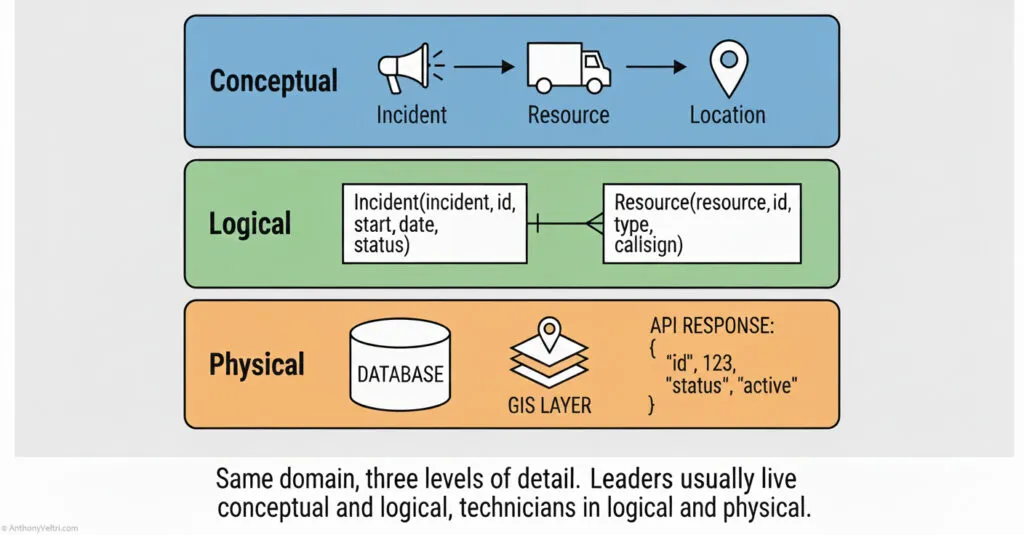

7. The Doctrine: Know What Room You Are In

The deeper lesson here is simple:

You must know what kind of room you are in

and what that room is actually for.

There are defense rooms:

- PhD committees.

- Technical review panels.

- Methodology workshops.

In those rooms, going deep on isotopes may be exactly the right move.

There are decision rooms:

- Funders deciding whether to renew your grant.

- Executives deciding whether to continue your program.

- Policy makers deciding which station survives the budget.

In those rooms, every minute spent defending a technical choice is a minute not spent:

- Showing what the work will change.

- Connecting it to the funder’s priorities.

- Making it clear what happens if the work stops.

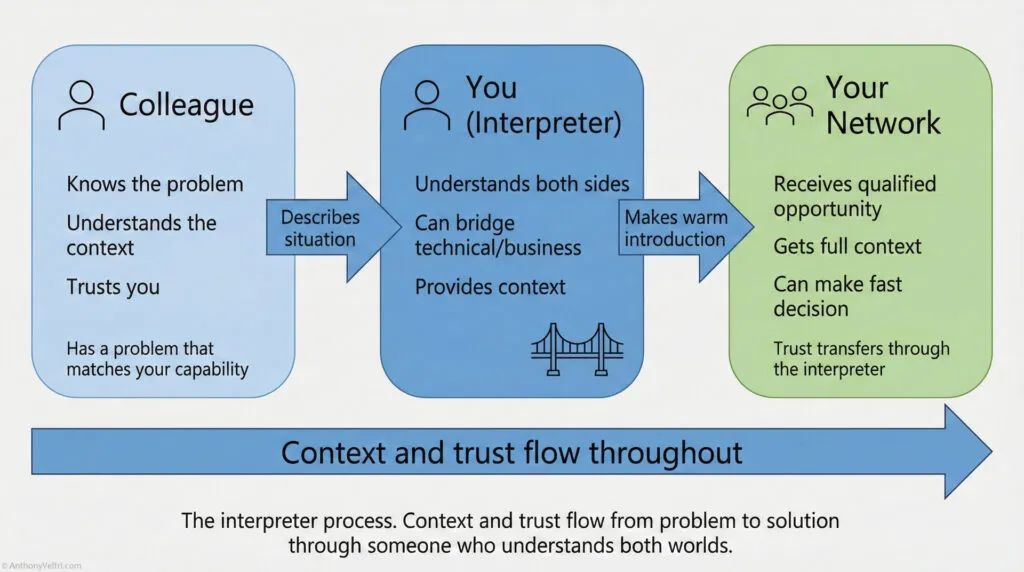

Scientists are rarely taught how to switch modes.

They bring the defense reflex into decision rooms,

and then wonder why decisions do not go their way.

8. Epilogue: Interviews, Legacy, and Why It Still Matters

The drive ended. We reached Hubbard Brook.

I was brought in as a videographer to document the physical archive. But the real work became the interviews. These scientists had decades of operational knowledge about long-term ecosystem research: how you maintain data integrity across generations of researchers, how you preserve context that isn’t in the published papers, what gets lost when funding disrupts continuity.

The interview approach wasn’t improvised. Early in my federal career as a physical scientist (2008), we received anti-elicitation training designed to prevent foreign intelligence from extracting sensitive information through casual conversation. Most people sat through it with glazed eyes. I found it fascinating.

I inverted the methodology. The same techniques that prevent unwanted knowledge extraction work brilliantly for constructive knowledge extraction when you have legitimate access and mission alignment. It’s the Perry Mason effect, but used for good.

I designed the interview protocol to extract tacit knowledge. The questions weren’t just “tell me about your research.” They were structured to capture operational patterns: decision points, failure modes, what worked when standard approaches didn’t.

It looks like casual conversation. It’s actually structured knowledge extraction with a thorough game plan. The approach only falls apart when someone treats every question like a deposition. Short of that level of defensiveness, it works like magic.

The resulting interviews became vital records – not just for the documentary, but as institutional memory for the research station and reference material for government funding decisions. The scientists told me afterward that articulating those patterns in the interviews helped them see their own work differently.

Over the weekend, I had the chance to:

- Interview Dr. Gene Likens and other scientists whose work defined the place.

- Capture stories about acid rain, forests, watersheds, and long-term experiments.

- See firsthand what happens when a community of researchers sticks with a landscape for decades.

Those interviews are a record of something rare.

An experimental forest that has outlived multiple funding cycles, fashions, and crises.

8.1 How Hubbard Brook leadership experienced the project

This is the same scientist from the car ride story above, recorded at the end of our rain-soaked, then sunny 60th anniversary weekend. Ten years ago I did not have language like ‘science is mute’ or ‘guard the room’ yet, but you can hear the pattern underneath how she describes the work and where she places the value.

In this short reflection, Dr. Lindsey Rustad talks about what it was like to bring me in cold for Hubbard Brook’s 60th anniversary, why she trusted me to handle the media side so she could focus on the science, and why she tells other research leaders to let me do my job and not micromanage the process. She also highlights what mattered most to her in the end: capturing the stories and people that never show up in Nature or in the methods section, but are what actually built the place.

The conversation in the car is just one vignette.

But it captures a pattern I see everywhere:

- Brilliant people.

- Important work.

- Meetings where the wrong question eats the whole agenda.

If you care about the survival of places like Hubbard Brook,

you cannot just be good at “the science”.

You have to get good at guarding the room.

8.2 A night of salamanders and stormlight

One of my favorite moments that weekend never showed up in any formal report. I asked Dr. Gene Likens about his most memorable night at Hubbard Brook, and instead of talking about a big discovery, he told a small story about salamanders, a storm, and his late wife.

It is exactly the kind of memory that explains why people devote their lives to a place, and exactly the kind of story that almost never makes it into the scientific record.

8.3 The physical memory of a forest

Behind the scenes there is another layer of story that rarely gets shown. Hubbard Brook is not only a set of plots and graphs. It is a physical archive of bottles, tree cores, and samples that reach back more than half a century.

A quick walk through part of the Hubbard Brook archive. Each bottle and core represents years of work and a continuous record that cannot be recreated if support collapses.

In recent years, funding uncertainty has put places like this under real pressure. When a site like Hubbard Brook is defunded, it is not just new experiments that disappear. The continuity of that physical record is at risk too.

Epilogue 2: The Physical Memory of a Forest

You guard the room to protect the questions we haven’t thought to ask yet. Ten years later, here’s why that skill matters more than ever:

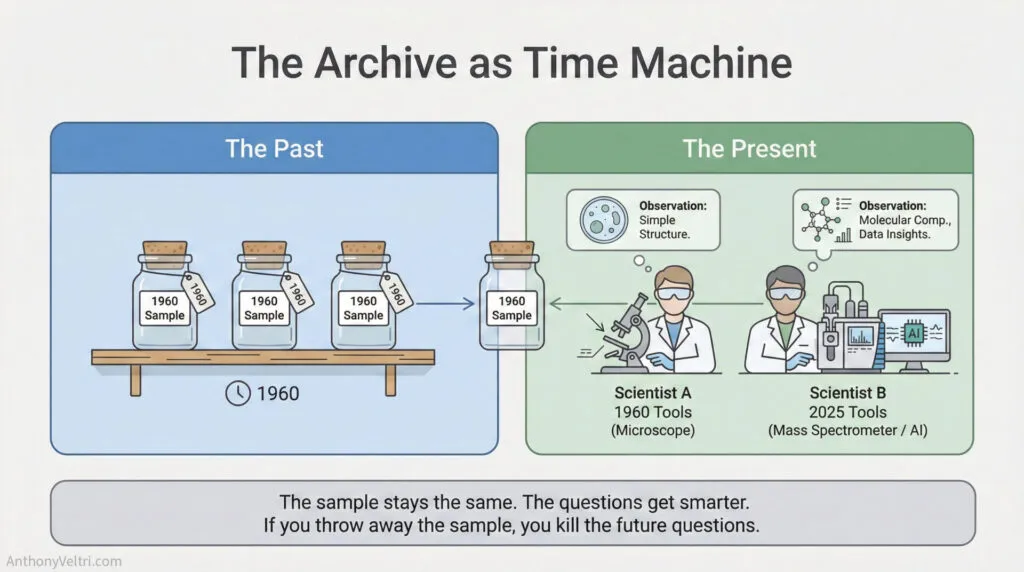

There is one more layer to the Hubbard Brook story that rarely makes it into the funding deck, but it should. We don’t keep physical samples to verify old numbers. We keep them because we don’t know what questions we’ll need to ask in 50 years.

The Archive as Time Machine: (if you haven’t watch the archive video, scroll up or click, here) The Hubbard Brook Physical Sample Archive is a building filled with thousands of bottles of water, soil, tree cores, and more dating back to the beginning of the study.

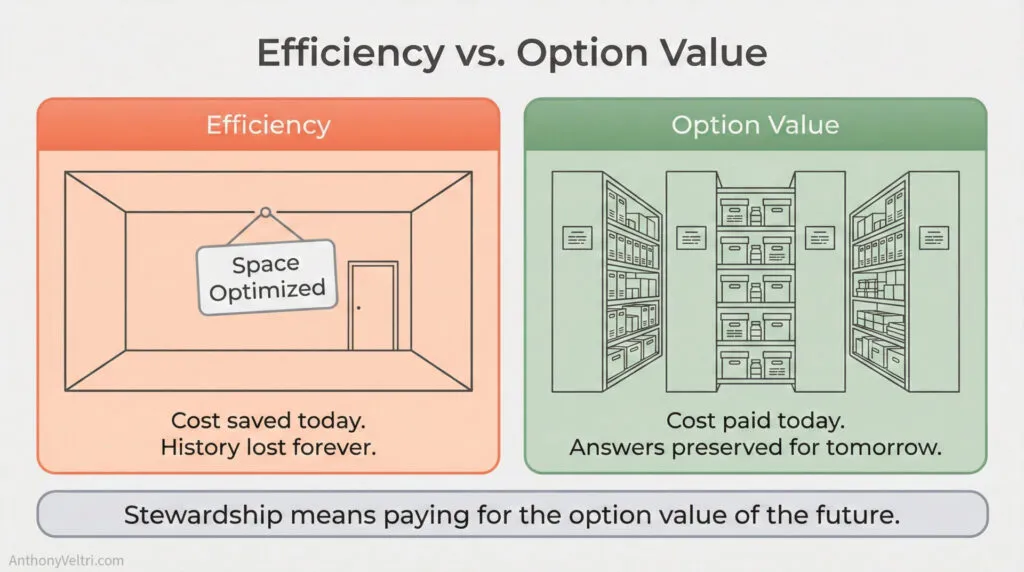

In an efficiency-obsessed world, this archive looks like a cost. It takes up space. It requires climate control. It requires cataloging. A consultant looking at a spreadsheet would ask: “Why are we storing water from 1965? We already measured it. We have the data.”

That question fundamentally misunderstands the nature of science.

As Dr. Lindsey Rustad explains, we don’t keep the samples just to verify old numbers. We keep them because we don’t know what questions we will need to ask in 50 years.

When those water samples were collected in 1965, we had no way to measure PFAS contamination. Today, with modern mass spectrometry, we can test those same bottles for forever chemicals and establish baseline contamination levels from before widespread PFAS use. That timeline is irreplaceable.

If we had only kept the data (the measurements we knew how to take at the time), we would be trapped in the knowledge of 1965. Because we kept the physical reality (the water itself), we can go back today with 2025 technology and ask 2025 questions of 1965 water.

The archive is not a storage unit. It is a time machine.

But when funding or infrastructure fails, that time machine is destroyed permanently.

In 2017, the Canadian Ice Core Archive at the University of Alberta lost 13% of its collection when a $4-million freezer system suffered a double malfunction. The refrigeration chillers shut down, and simultaneously, the monitoring system failed due to database corruption. Temperatures inside the freezer soared to 40°C (100°F). The melted samples represented more than 80,000 years of climate history from the Canadian Arctic. This was irreplaceable baseline data from glaciers that no longer exist in their original form.

As glaciologist Martin Sharp explained: “When you lose part of an ice core, you lose part of the record of past climates, past environments; an archive of the history of our atmosphere. You just don’t have easy access to information about those past time periods.”

Those samples can never be replaced. Future scientists will have a permanent gap in the baseline data they need to understand how our climate is changing. Questions we haven’t thought to ask yet (questions about atmospheric composition, industrial pollutants, or environmental changes we don’t even know to look for) can no longer be answered using that portion of the Arctic record.

This is what happens when we treat archives as costs instead of option value.

Destroying an archive to save money on rent is like paving over a seed bank to build a disco or golf course. You’re trading future adaptability for present efficiency

This is why you must Know What Room You Are In.

If you are in a Defense Room (technical), you can argue about storage protocols and cataloging methods.

But when you are in a Decision Room (funding), you are not arguing for storage space. You are arguing for the survival of the system’s memory. If you fail to guard that room (if you let the conversation drift into “efficiency” or “cost per square foot” without anchoring it in the option value of the future) the archive dies. And once it is gone, no amount of technical brilliance can bring it back.

Truth is slow. Efficiency is fast. You have to choose.

Ten years after filming the archive, the lesson has crystallized. If you measure a forest for three years, you see noise; if you measure it for thirty, you see the climate change. This briefing connects the physical stewardship of those samples to the digital stewardship of government data. We have enough innovators; we need more guardians willing to stand in the doorway and say “No” to the Good Idea Fairy.

(Note: The historical footage of the archive walk-through is located above in Section 8.3)

9. How to Apply This in Your Own Work

You do not need to be at an experimental forest for this to matter.

If you are a scientist, technical lead, or subject matter expert, try this:

9.1 Before your next big meeting

Write down, in one or two sentences:

- What this meeting is actually for.

- “Secure funding for year three.”

- “Get a go or no go decision on the next phase.”

- “Agree on which program gets priority.”

This is your North Star.

9.2 During Q and A

For each question, scan:

- Does answering this move us closer to that purpose?

- Or is it off on a technical branch?

If it is off-branch, use a variant of:

“That is an important technical detail, and I am happy to go deeper with you after this.

For now, I want to keep us focused on [decision or outcome].”

You will feel the pull to dive in. That is normal. That is your conditioning.

Your job is to notice it and choose differently.

9.3 After the meeting

Ask yourself:

- How much time did we spend on method versus mission?

- Did I let someone’s curiosity or ego steer us off the decision we needed?

- What language could I have used to park those questions sooner?

Turn that reflection into a small script you keep handy.

10. Science Is Mute, But You Do Not Have To Be

This Hubbard Brook story is not about one scientist or one car ride. It is about a structural reality:

- Meetings are short.

- Attention is shorter.

People who hold the purse strings are not grading you on your mastery of isotopes. They are deciding, quietly:

“Do I believe this is worth scarce money and political capital?”

You do not need to become a marketer or a politician.

You do need to:

- Know what room you are in.

- Guard the agenda.

- Answer the right questions, at the right depth, for the right audience.

That is not a betrayal of science.

It is the only way a place like Hubbard Brook survives long enough for the science to matter.

Last Updated on March 2, 2026