Guardrails, Not Gates: Designing Systems That Bend Without Breaking

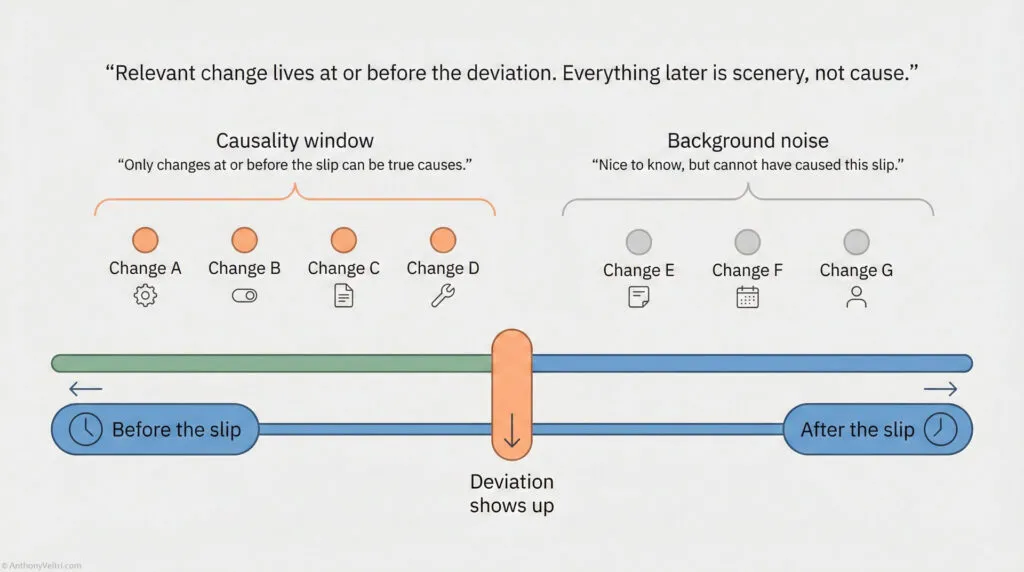

There is a quiet failure mode in complex systems. It happens when every risk becomes a gate.

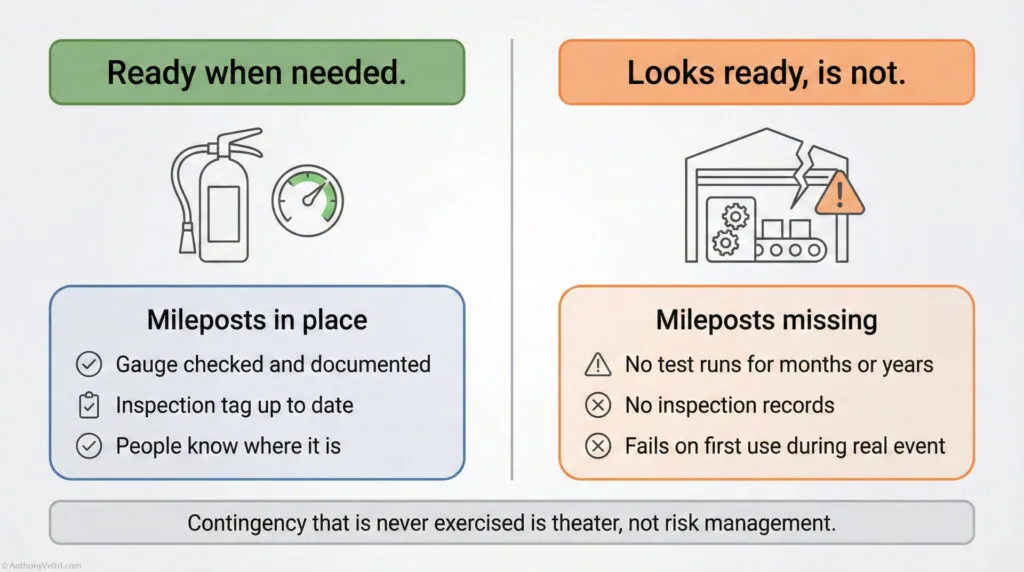

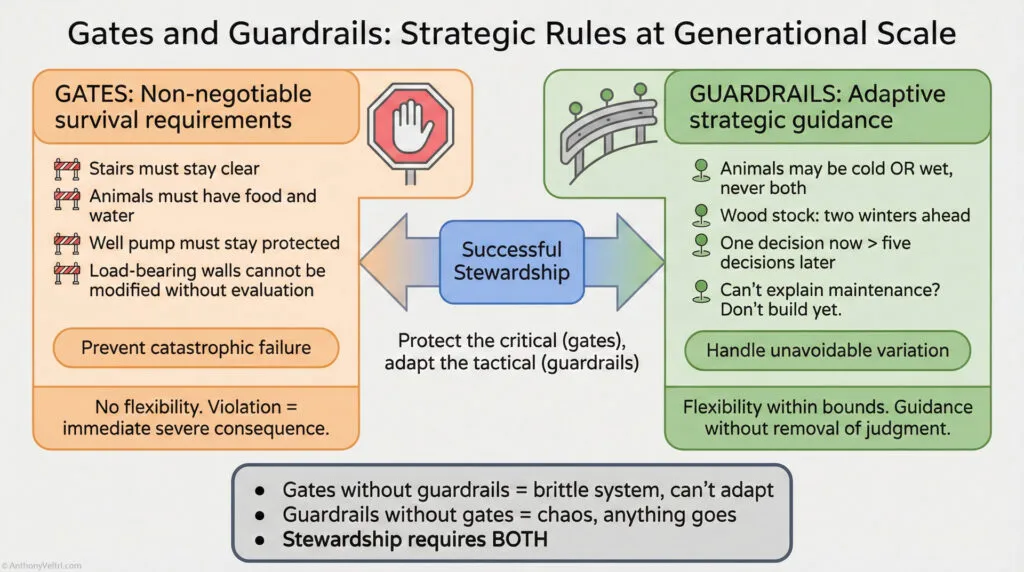

A gate is a hard stop. You may not proceed until you satisfy this checklist, this committee, this form. Gates have their place. Nobody wants to remove all gates from an air traffic control system or a nuclear plant.

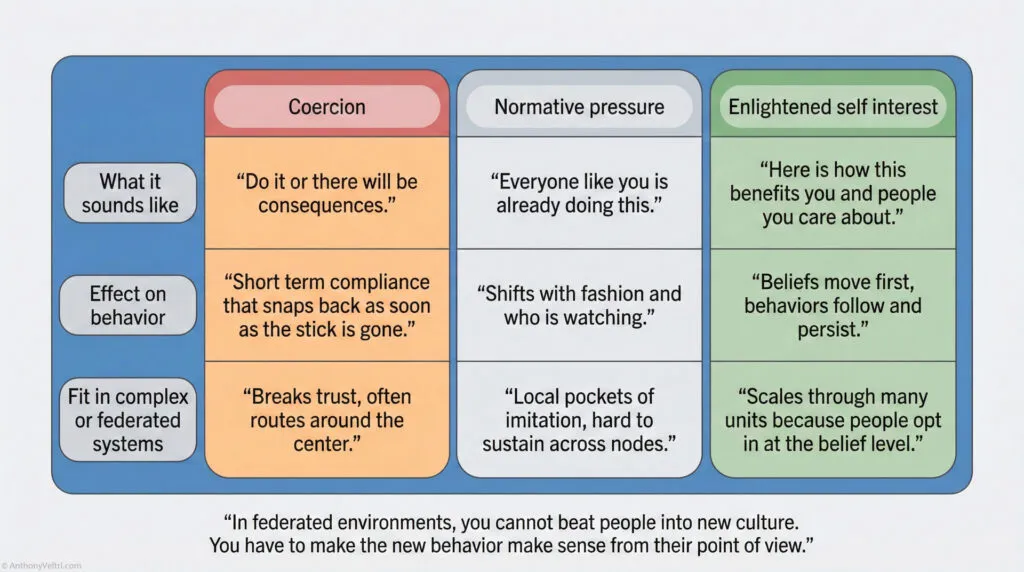

The problem starts when everyday work is littered with gates that were originally written for exceptional situations. Over time, people learn to route around them. Work moves into spreadsheets, shadow systems, and side conversations. The official process is honored on paper. Reality splits off into something else.

A guardrail works differently. It defines a boundary and a fall zone, then leaves freedom inside that zone. You know where the edge is. You know what happens if you cross it. Inside the rail there are many valid paths, not just one.

In my architecture work across Homeland Security, wildland fire, and civilian agencies, guardrails have consistently outperformed gates.

When we moved iCAV from Mount Weather to Stennis, the temptation was to gate every change. The system was critical for infrastructure and incident awareness. Outages were politically visible. The Change Advisory Board could have turned into a giant red stop sign.

Instead, we defined a few non-negotiables.

- Data integrity and security could not be compromised.

- There had to be a credible rollback plan.

- Partners needed continuity of access even if they did not care which data center they were hitting.

Inside those constraints, we allowed teams to experiment and iterate. We documented patterns that worked and encouraged reuse. The CAB became more like a guardrail steward than a gatekeeper. We did not eliminate risk. We made it visible and manageable.

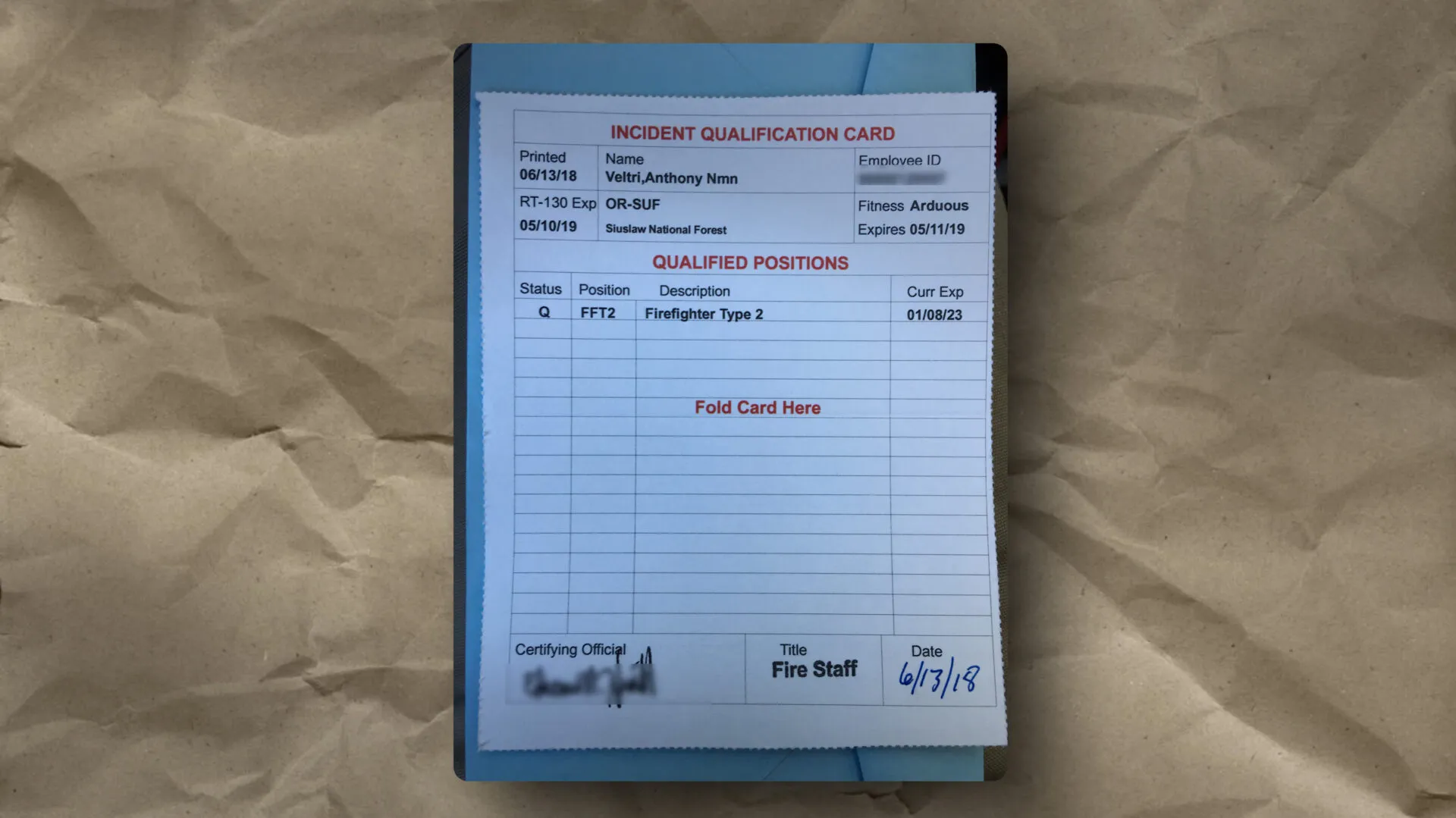

The wildland fire community unintentionally teaches the same lesson. NWCG has serious doctrine. When you move resources through ROSS or log an incident in IRWIN, you do not get to improvise on core fields. Aviation safety and life safety are on the line.

At the same time, that doctrine leaves room for local judgment. Incident commanders are not reading a script. They operate inside guardrails shaped by fatality investigations and hard won experience. The rules are strict where violation kills people. Elsewhere, they trust professionals to think.

My doctrine for guardrails over gates is this:

- Turn true existential risks into guardrails, not paperwork. Make the boundary vivid and the consequence clear.

- Design for adults (competent professionals), not children (an inexperienced person). Assume your professionals want to do the right thing, then give them a lane wide enough to maneuver.

- Measure behavior in the system, not only compliance with procedure. If the work is happening outside your process, your gates are not securing anything. They are only hiding the real system from you.

The Reality Gap: When you rely on gates, you measure the Blue Line (Standard). But if the work has moved to spreadsheets to bypass the gate, the Green Line (Actual Reality) deviates, and you are flying blind.

This applies as much to digital platforms as it does to organizations and families. If your cloud architecture has a different process for every small exception, you do not have a process. You have a museum.

Guardrails ask a harder design question. What must never happen. What must always be true. Then they get out of the way.

Last Updated on December 9, 2025