Reusable architectural, leadership, and workflow patterns that stabilize systems and accelerate mission tempo #

Doctrine Claim: Systems fail when every problem is treated as unique. High-tempo organizations survive by recognizing patterns: “This is a federation problem,” “This is an interface problem” Then we apply pre-validated solutions. This Annex is your library of structural shortcuts.

1. Purpose of the Pattern Library #

Patterns are reusable solutions to recurring problems.

They give you:

- shorthand

- predictability

- shared vocabulary

- architectural discipline

- leadership consistency

- reduced cognitive load

Patterns accelerate thinking because they let you recognize the shape of a problem instantly.

This annex collects the patterns that appear repeatedly across:

- mission systems

- bureaucratic systems

- high visibility workflows

- data pipelines

- distributed teams

- federated environments

This is your toolbox.

2. How to Use This Pattern Library #

Each pattern includes:

- Name

- Problem

- Pattern description

- Where it applies

- Example (iCAV or FRN)

- Failure mode if ignored

- Cross links to doctrine

Each pattern is standalone and reusable.

Patterns are intentionally short so that your expansion posts can go deep when needed.

3. The Patterns #

Below are the foundational patterns recommended for your doctrine.

We can add more at any time.

Pattern 1: Two Owner Interface #

Problem:

Boundaries fail because nobody owns both sides.

Pattern:

Every interface must have two named owners, one upstream and one downstream.

Applies to:

APIs, schemas, workflows, approvals, handoffs, leadership coordination.

Example:

In FRNs, once owners were defined for each stage of the workflow (editorial, legal review, leadership approval, formatting, publication) the thrash disappeared.

Failure mode:

Conflict, drift, finger pointing.

Cross links:

Annex C, Human Contracts, Data Contracts.

Pattern 2: Intent First #

Problem:

Teams optimize for tasks, not outcomes.

Pattern:

Start every boundary, workflow, or decision by stating the intent.

Applies to:

FRNs, ingest design, partner coordination, mission activations, leadership communication.

Example:

In iCAV, clarity of operational intent allowed analysts to act without waiting for approval.

Failure mode:

Misalignment, rework, political drift.

Cross links:

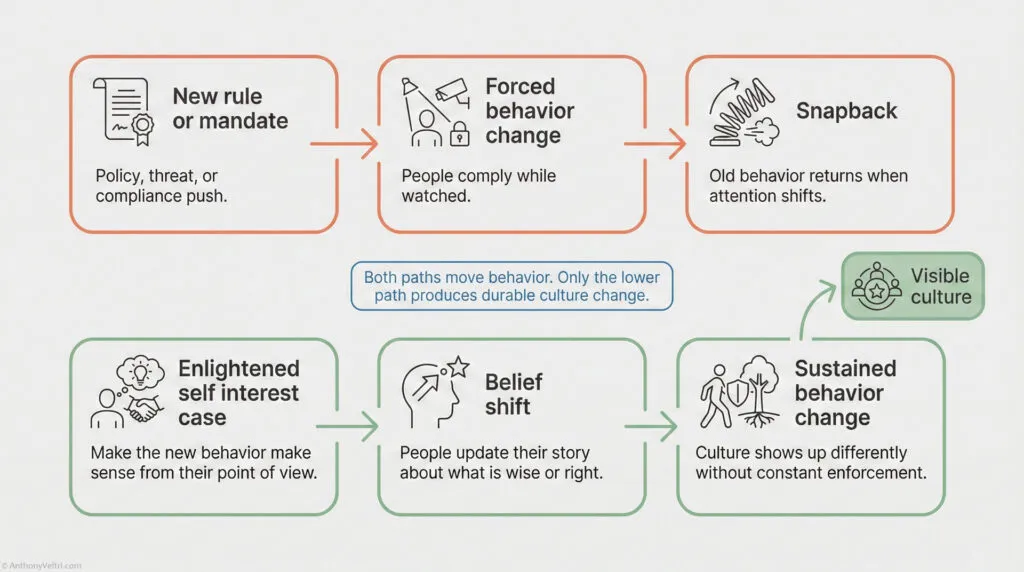

Clear Intent, Commitment vs Compliance.

Pattern 3: Minimum Viable Publication #

Problem:

Teams freeze when requirements are disrupted.

Pattern:

Define the smallest acceptable output during degraded conditions.

Applies to:

Data ingest, FRNs, reporting cycles, compliance tasks, partner feeds.

Example:

During FRN crises, the team stabilized quality by defining what absolutely had to be correct vs what could be fixed later.

Failure mode:

Deadline failure, panic escalation.

Cross links:

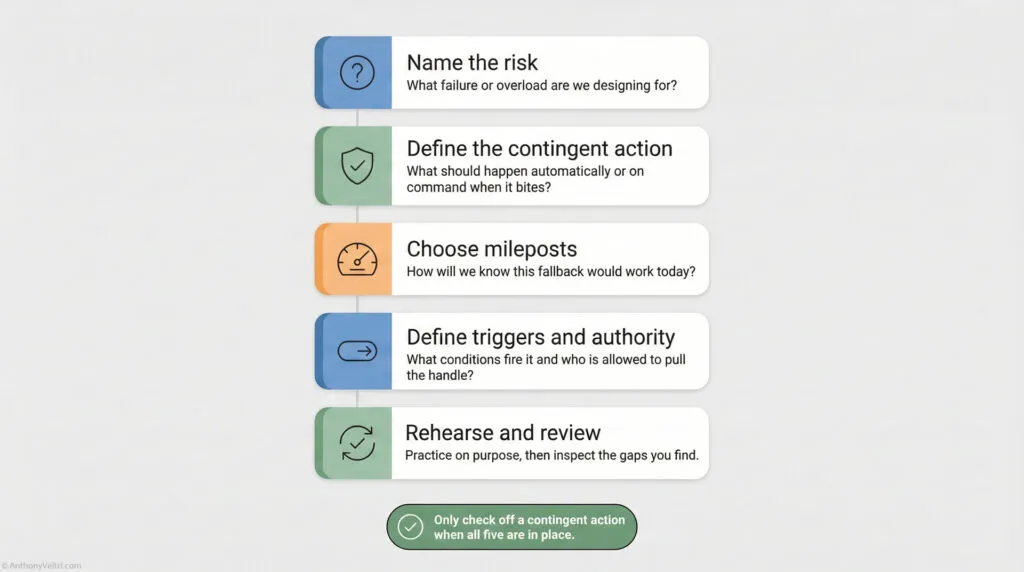

Degraded Operations, Prevention–Contingency Matrix.

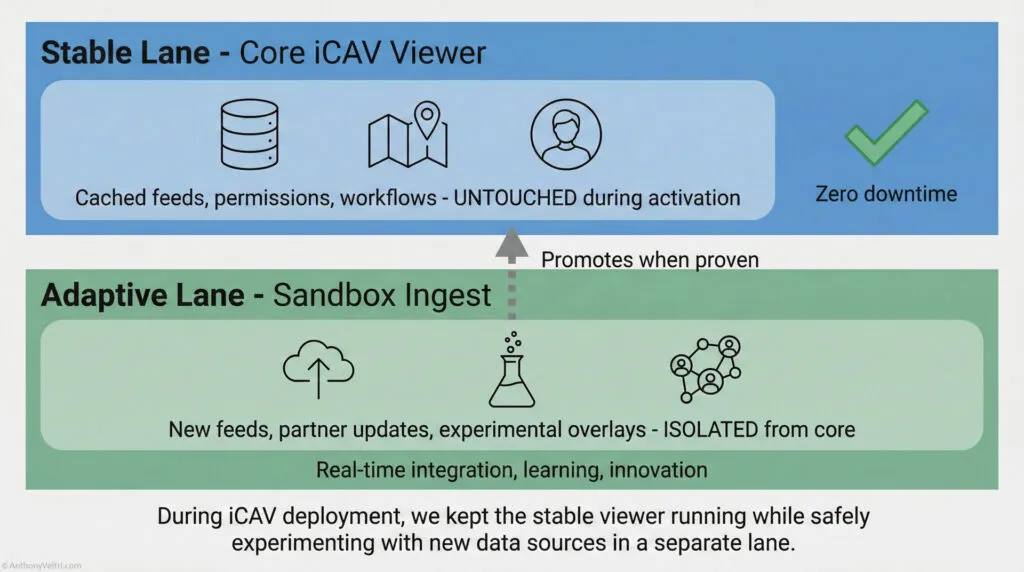

Pattern 4: Last Known Good #

Problem:

Live systems break under drift or outage.

Pattern:

Cache and serve the last known valid state when new data is unavailable.

Applies to:

iCAV ingest, dashboards, reporting, partner feeds.

Example:

iCAV’s cached layers allowed operations to continue even when partners were offline.

Failure mode:

Blind spots, downtime, inaccurate decision making.

Cross links:

Contingent Design, Emergent Resilience.

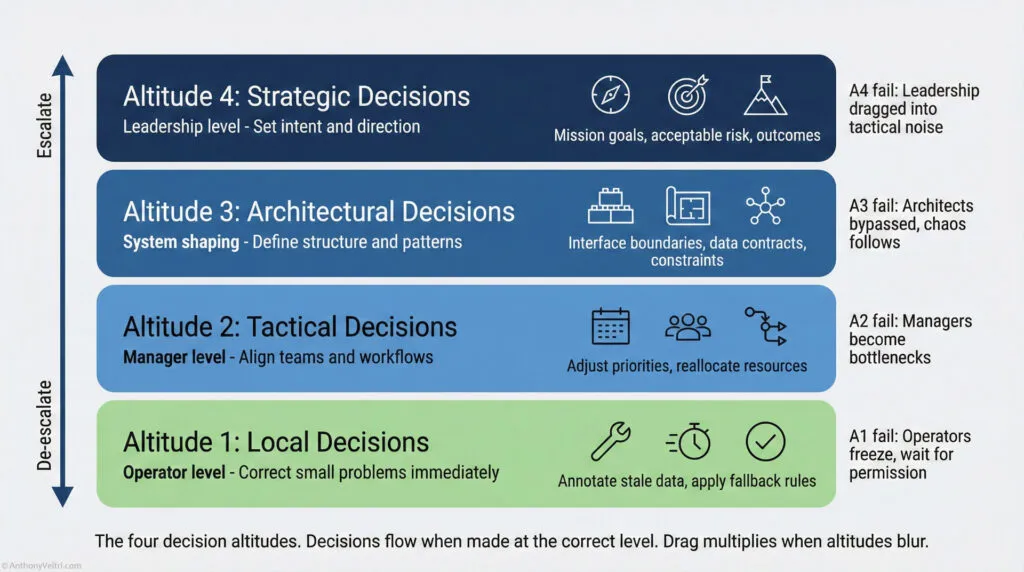

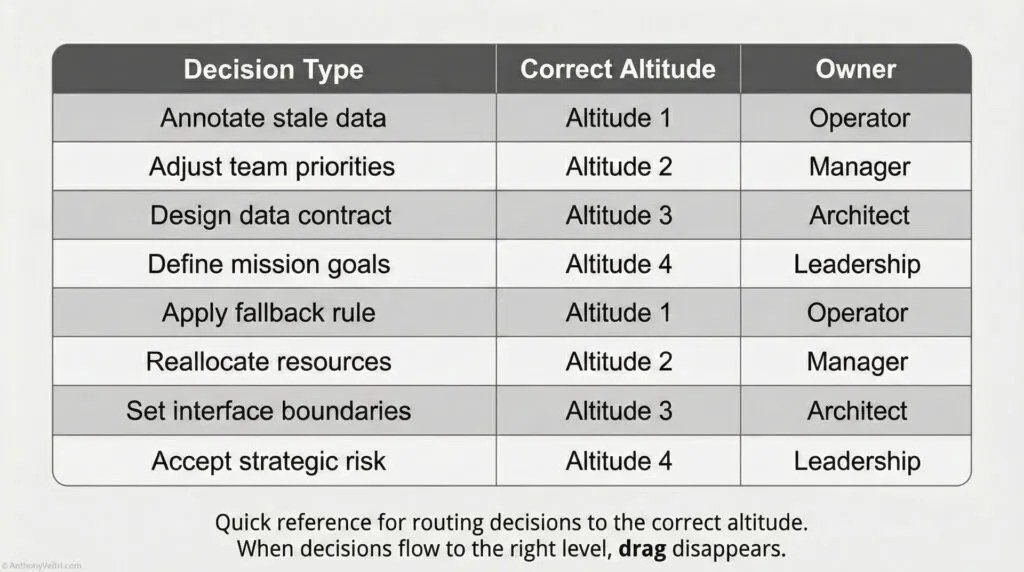

Pattern 5: Tight Loops for Operators, Wide Loops for Leaders #

Problem:

Leaders get pulled into minor issues. Operators wait too long for approval.

Pattern:

Operators run fast, small loops. Leaders run slow, strategic loops.

Applies to:

FRNs, portfolio reviews, architectural decisions, escalations.

Example:

In FRNs, once leadership stopped making formatting requests during late stage review, operator tempo increased.

Failure mode:

Decision drag, micromanagement.

Cross links:

Decision Altitudes, Leadership vs Management vs Supervision.

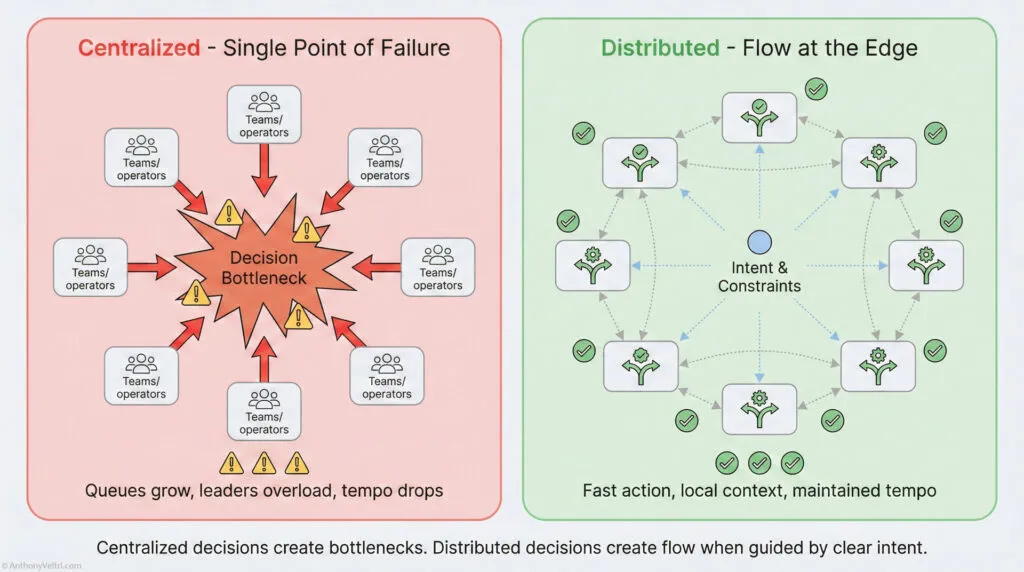

Pattern 6: Default to Autonomy Within Boundaries #

Problem:

People wait when they do not need to.

Pattern:

Empower operators with freedom inside clearly defined boundaries.

Applies to:

Mission systems, editorial workflows, engineering teams.

Example:

iCAV analysts corrected map issues instantly because the boundaries were clear.

Failure mode:

Escalation overload, lost tempo.

Cross links:

Commitment vs Compliance, Distributed Decisions.

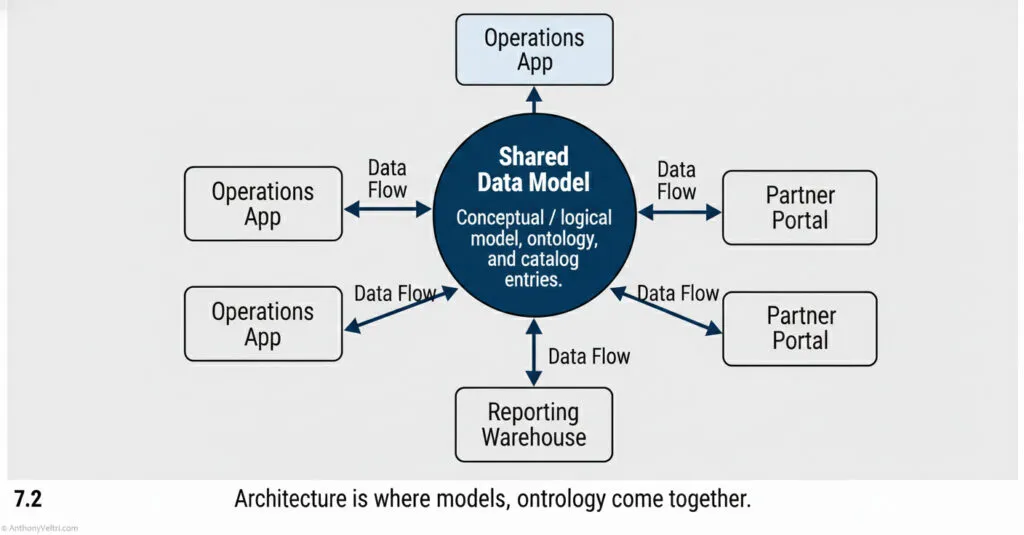

Pattern 7: Single Source of Meaning #

Problem:

Multiple groups interpret the same field or rule differently.

Pattern:

One canonical definition for data, intent, or correctness.

Applies to:

FRNs (perfect example), schemas, status fields, reporting metrics.

Example:

FRN workflow stabilized when the team created unified definitions for fields that leadership had previously altered mid cycle.

Failure mode:

Contradictory outputs, leadership thrash.

Cross links:

Data Contracts, Human Contracts.

Pattern 8: Fallback First #

Problem:

Systems assume everything works perfectly.

Pattern:

Design fallback behavior before designing the primary path.

Applies to:

Ingest, APIs, publication workflows, partner coordination.

Example:

iCAV always accepted partial truth, not just perfect truth.

Failure mode:

Total collapse under minor failures.

Cross links:

Contingent Design, Prevention–Contingency Matrix.

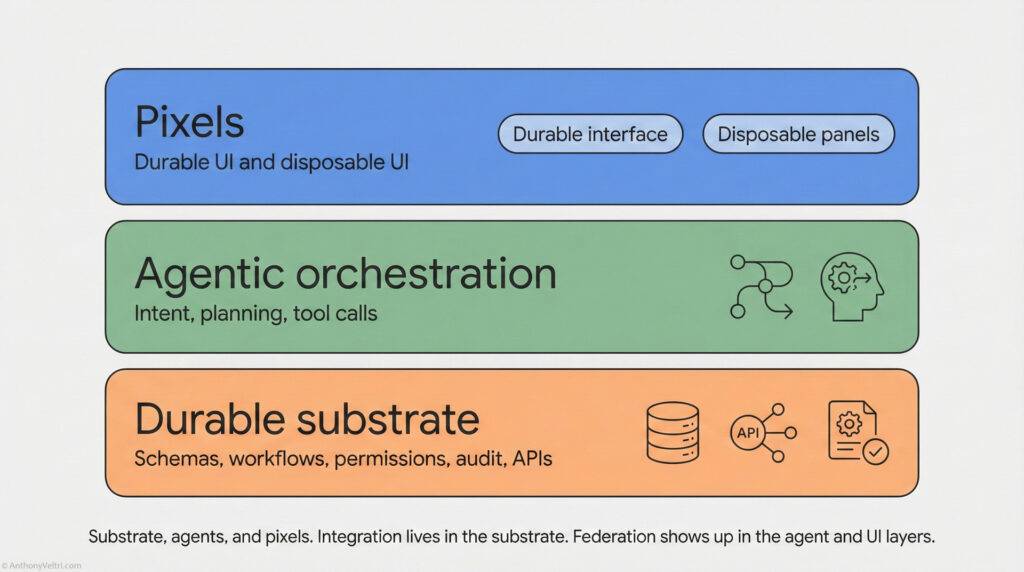

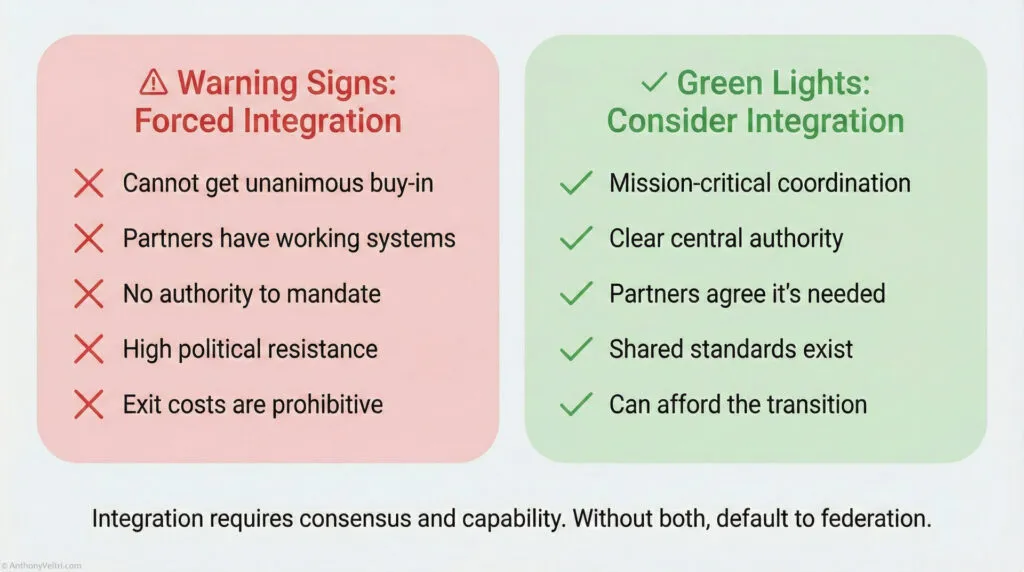

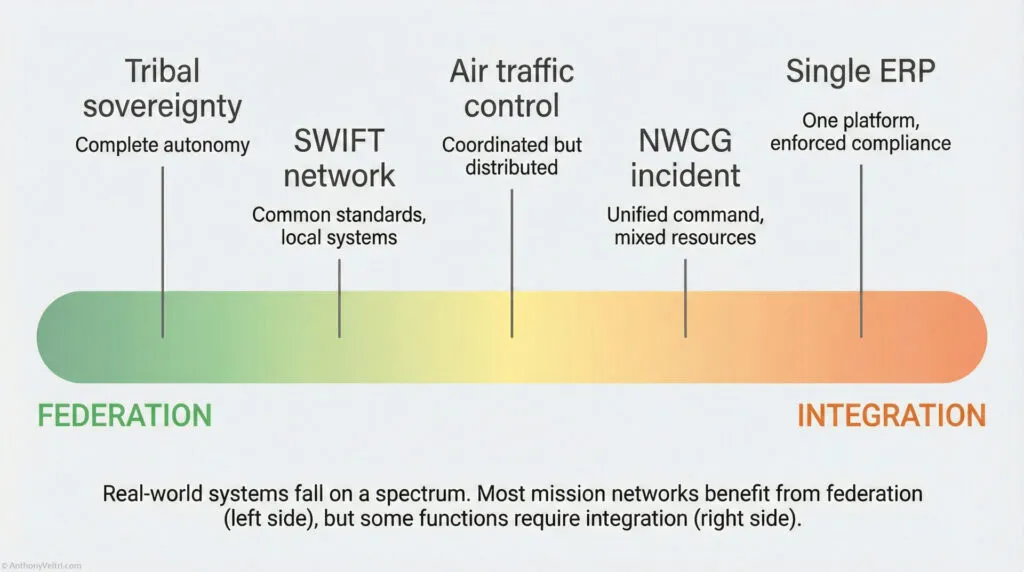

Pattern 9: Federated First, Integrate Only When Necessary #

Problem:

Centralization increases fragility and political resistance.

Pattern:

Allow diversity at the edge, harmonize in the middle, display at the top.

Applies to:

Mission networks, governance, FRN multi team contributions.

Example:

iCAV succeeded because partners kept their own systems and still fed the picture.

Failure mode:

Resistance, delays, brittle architecture.

Cross links:

Federation vs Integration.

Pattern 10: Drift Detection #

Problem:

Silent degradation causes failure before anyone notices.

Pattern:

Actively monitor for time drift, schema drift, content drift, process drift.

Applies to:

Ingest systems, FRN revisions, code, workflows, legal compliance.

Example:

FRN failures often emerged because fields silently changed and no one detected drift.

Failure mode:

Late stage breakdown, crisis escalation.

Cross links:

Data Contracts, Interface Ownership.

Pattern 11: Escalate by Altitude, Not Emotion #

Problem:

People escalate based on frustration instead of correct authority.

Pattern:

Escalation must follow altitude logic. Operator issues go operator to manager, not operator to leadership.

Applies to:

All mission and bureaucratic environments.

Example:

FRN chaos reduced when escalations followed a predictable path instead of reaching leadership prematurely.

Failure mode:

Leadership overload, political heat, decision paralysis.

Cross links:

Decision Altitudes.

Pattern 12: Clarity Beats Precision #

Problem:

Teams optimize the small details and miss the point.

Pattern:

Clear intent and boundaries matter more than perfect detail.

Applies to:

FRNs, data ingest, user stories, mission briefs.

Example:

iCAV analysts needed clarity on what mattered, not pixel-exact correctness.

Failure mode:

Perfectionism, rework, lost tempo.

Cross links:

Clear Intent, Commitment vs Compliance.

Pattern 13: Golden Dataset Spine #

Problem:

Multiple systems report different answers for the same question. Leaders argue about which report is right instead of what to do.

Pattern:

For any high-value domain, define a golden dataset that acts as the authoritative spine. Give it a clear scope, a named owner and a published schema. All applications become clients of that spine.

Applies to:

Critical infrastructure views, incident records, asset inventories, key performance metrics, shared reference data.

Example:

Instead of each iCAV consumer maintaining a separate infrastructure list, a curated infrastructure dataset becomes the single approved source for “sites we show to decision makers,” with clear rules for inclusion and update.

Failure mode:

Five versions of reality. Endless reconciliation, political fights over whose report is “right,” and ad hoc spreadsheets acting as shadow golden sources.

Cross links:

Golden Datasets, Portfolio Thinking, Single Source of Meaning, Data Contracts.

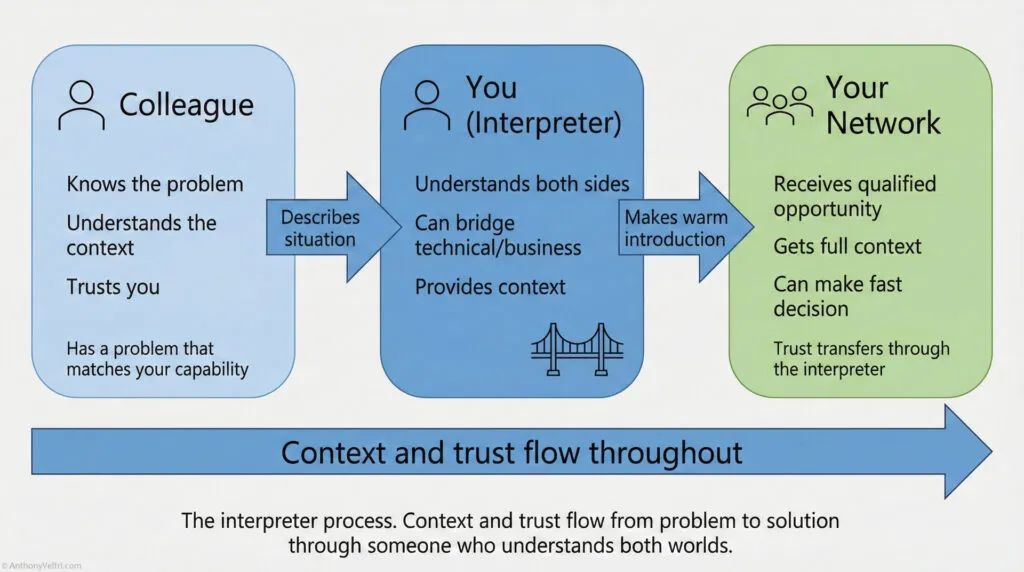

Pattern 14: Human As Interface Detector #

Problem:

Critical information flow depends on one over responsible person who bridges tools, teams or layers in their head and calendar.

Pattern:

Treat any human who routinely glues systems together as a sensor. Wherever they are the only interface, either formalize that boundary (API, contract, role) or redesign so the system carries its own messages.

Applies to:

Mission systems, FRN workflows, cross team handoffs, stakeholder briefings, alliance coordination.

Example:

A branch chief who spends mornings configuring servers and afternoons briefing executives on the same system exposes missing integration and unclear contracts. Those stress points mark where new interfaces and roles are needed.

Failure mode:

Single point of failure, burnout, opaque decisions and a system that collapses when that person burns out or leaves.

Cross links:

Interfaces Break First, Interface Ownership, Human Contracts, Decision Altitudes.

Pattern 15: Roles As Protocols (Task Book Model) #

Problem:

Roles are defined as job titles or personalities, not as repeatable functions. People cannot be swapped across teams or agencies in a crisis.

Pattern:

Define roles as protocols with observable behaviors and shared expectations. Use task book style qualification: real tasks, observed in the field, signed off by qualified peers. Design so a qualified person from another unit can plug in after a briefing.

Applies to:

Incident management, operations centers, editorial and review roles, product ownership, portfolio governance.

Example:

NWCG task books for Incident Commander, dispatcher or helicopter manager define the role so clearly that an IC from another agency can take over at the end of an operational period and continue seamlessly.

Failure mode:

Non portable roles, dependence on local “heroes,” stalled operations when one person is unavailable and steep learning curves any time you shift people.

Cross links:

Commitment Outperforms Compliance, Leadership vs Management vs Supervision, Federation vs Integration, Decision Altitudes.

Pattern 16: Honest Freshness #

Problem:

Data ages unevenly across partners and systems. Visuals pretend everything is current even when parts of the picture are stale.

Pattern:

Accept and display uneven freshness. Track update times, show them in the interface, and treat “age of data” as a first-class field so decision makers can weigh quality explicitly.

Applies to:

Geospatial layers, incident dashboards, partner feeds, compliance reports, any federated data product.

Example:

In iCAV, some partners updated infrastructure data frequently and others sent DVDs sporadically. Instead of hiding the gap, the system can show age indicators or quality codes so operators know which regions are running on older truth.

Failure mode:

False confidence. People act on maps or metrics that look current but silently lag reality, leading to bad allocation, missed risk and broken trust when discrepancies surface.

Cross links:

Federated First, Last Known Good, Drift Detection, Data Contracts.

Pattern 17: Duplication As Signal #

Problem:

Multiple teams invest in overlapping data or projects without coordination. Everyone treats duplication as waste, not as a diagnostic.

Pattern:

Treat repeated effort and overlapping datasets as signals of missing portfolio governance or golden spines. When you find duplicate investments, ask what shared product or standard they are quietly voting for with their budget.

Applies to:

LIDAR and remote sensing programs, analytics projects, microservices sprawl, internal tools that replicate features.

Example:

Overlapping LIDAR flights by different units within the same agency reveal a latent need for a shared elevation product. On fires, the same players voluntarily coordinate aviation and perimeter data because the risk is obvious.

Failure mode:

Chronic waste, incompatible datasets, and political turf battles over whose tool survives, instead of a clear decision about what deserves golden treatment.

Cross links:

Portfolio Thinking, Golden Datasets, Federation vs Integration.

Pattern 18: Agent Of Agents (AI At The Interface) #

Problem:

Federated systems drift apart faster than humans can monitor. Analysts become manual glue between many feeds and tools.

Pattern:

Place AI agents at key interfaces to observe, compare and summarize across systems. Let them propose mappings, flag divergences and predict freshness issues, while humans retain judgment and ownership.

Applies to:

Multi system data pipelines, alliance level information sharing, monitoring partner feeds, schema reconciliation.

Example:

An AI agent watches several incident feeds, detects potential duplicates and naming differences, and surfaces a simple “possible match” list to human operators instead of expecting people to eyeball every incoming record.

Failure mode:

Either no automation at all and humans drown in reconciliation work, or opaque AI that silently edits reality and destroys trust because its actions are invisible and unowned.

Cross links:

Data Contracts, Interface Ownership, Federated First, AI Governance (future annex).

Pattern 19: Mission Scoped Standardization #

Problem:

Either everything is forced into one standard, creating resistance and fragility, or nothing is standardized and shared work collapses.

Pattern:

Standardize narrowly where life safety or core mission outcomes demand it. Allow federation elsewhere. Make the “standardized slice” explicit and tied to a specific mission, not a vague desire for neatness.

Applies to:

Ammunition and magazines, medical standards like FHIR, incident records, core reference codes, aviation safety data.

Example:

NWCG agencies that are normally federated voluntarily conform to shared incident, aviation and resource ordering standards for fires, while keeping their home business systems and records independent outside that domain.

Failure mode:

Either over centralization that partners quietly work around, or under standardization where critical functions like aviation safety depend on “whatever the local system does.”

Cross links:

Federation vs Integration, Useful Interoperability, Golden Datasets, Commitment vs Compliance.

Pattern 20: Partnership Sovereignty Guardrail #

Problem:

External partners fear that sharing data or accepting support will turn into loss of control over their community or mission.

Pattern:

Make sovereignty a first class design constraint. Define what remains under local control, what is shared, and how shared resources are governed. Model relationships as partnerships, not master servant abstractions.

Applies to:

Disaster response, tribal and municipal partnerships, NGO and relief coordination, alliance environments.

Example:

In Bay St Louis, the pastor accepted supplies but rejected an external organization’s attempt to manage all resources, including those already on site. A better pattern would have defined “you own what you bring, we own local context, we co-own the plan.”

Failure mode:

Resistance, slow or blocked data sharing, public pushback, and brittle relationships that fracture under pressure.

Cross links:

Federation vs Integration, Human Contracts, When You Cannot Force Compliance.

Pattern 21: Commitment As Ritual #

Problem:

Commitment is treated as a feeling or speech, not as a concrete, testable behavior.

Pattern:

Encode commitment into visible rituals and artifacts that require real effort. Use check rides, task books, briefings, and after action reviews that demonstrate commitment through action, not slogans.

Applies to:

ICS roles, technical leadership, editorial review, portfolio governance, onboarding, disaster response, training programs.

Example:

NWCG task books turn “I am committed” into a sequence of real tasks observed and signed off by qualified peers. The signature is a public statement: “I have seen this person perform under real conditions and I stake my name on it.”

Failure mode:

Leaders give speeches about commitment while systems reward compliance and box checking. People say the right words, then fail under stress because nothing in the system ever demanded real proof.

Cross-links:

Commitment Outperforms Compliance, Roles As Protocols, Leadership vs Management vs Supervision, Human Contracts.

Pattern 22: Staging Areas Are The Wrong Time To Start Trust #

Problem:

Partners first meet each other in the parking lot of a disaster. They are forced to negotiate roles and sovereignty in the middle of chaos.

Pattern:

Build relationships, doctrine and expectations before the crisis. Use exercises, pre-season meetings, MOUs and shared training so that by the time you hit the staging area, you are executing a known playbook, not inventing one.

Applies to:

Disaster response, wildland fire, alliance operations centers, cross-agency projects, NGO and vendor coordination.

Example:

In Bay St Louis, described in “Katrina, A Journey of Hope,” a relief organization arrived with trucks of supplies and tried to take control of all resources on site, including those already organized by the local church. The pastor had to defend his community’s sovereignty on the spot. With pre-existing agreements and shared doctrine, that conversation would have been a check in, not a confrontation.

Failure mode:

Power struggles at the edge of the disaster, slow ramp up, duplicated effort, offended locals and brittle partnerships that fracture as soon as stress hits.

Cross-links:

When You Cannot Force Compliance, Partnership Sovereignty Guardrail, Federation vs Integration, Human Contracts.

Pattern 23: Pre Commit To Degraded Modes #

Problem:

Systems and teams assume full functionality. When something breaks, nobody knows what the “good enough” version looks like, so they either freeze or improvise under stress.

Pattern:

Define degraded modes in advance. Decide what you will still do, what you will stop doing and what the minimum viable output is when inputs, tools or staff are compromised. Write this into playbooks and rehearse it.

Applies to:

iCAV ingest, FRN publication, incident reporting, dashboards, alliance communications, any time-bound workflow.

Example:

A publication team agrees that in a degraded mode they will release a stripped-down FRN with validated core fields only, defer non-critical formatting and commentary, and log what was skipped for later correction. This prevents total deadline failure when one part of the process is down.

Failure mode:

All or nothing behavior. Minor outages cause full stop, or ad hoc shortcuts get taken without shared understanding, leading to finger pointing and loss of trust in outputs.

Cross links:

Minimum Viable Publication, Fallback First, Last Known Good, Prevention–Contingency Matrix, Degraded Operations.

Pattern 24: Proudly Maintained By #

Problem:

When ownership is anonymous, commitment decays and systems quietly rot. Nobody feels personally responsible for long-term health.

Pattern:

Make stewardship visible and personal. Attach names to critical systems, datasets and workflows so there is a clear human owner who can say “this is mine” with pride.

Applies to:

Mission systems, golden datasets, critical services, run books, key interfaces, hardware assets.

Example:

On a Hoover Dam turbine, a brass plate reads “Proudly Maintained By Mike E.” It is not a sticker or a temporary tag. It is a permanent declaration of stewardship. Mike becomes a known guardian of that system, not an interchangeable resource.

Failure mode:

Everything is “owned” by a team, a department or “the organization.” Excellence disappears into the crowd. When something fails, blame bounces around and nobody feels shame or pride in the result.

Cross links:

Commitment Outperforms Compliance, Commitment As Ritual, Interface Ownership, Human Contracts.

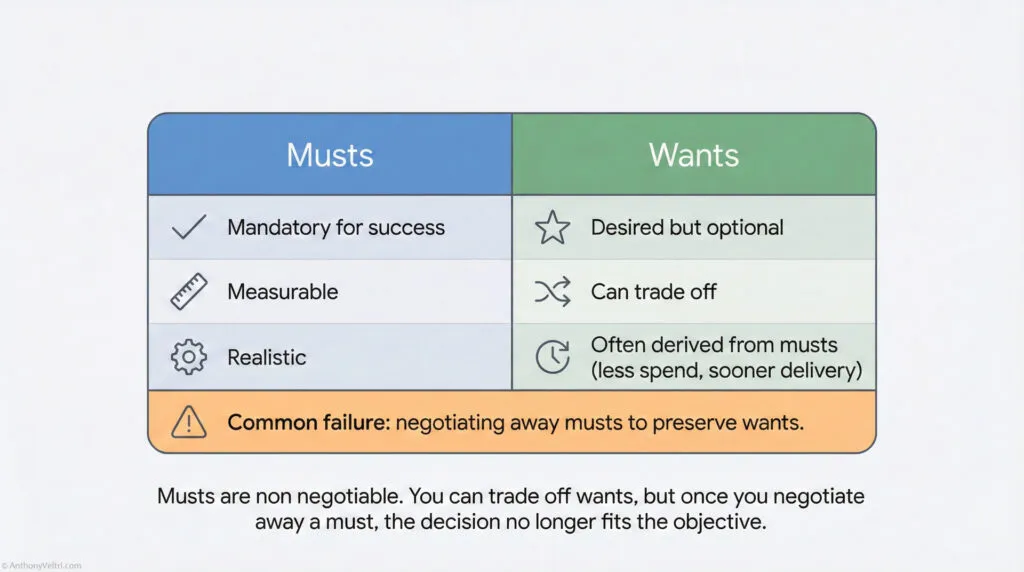

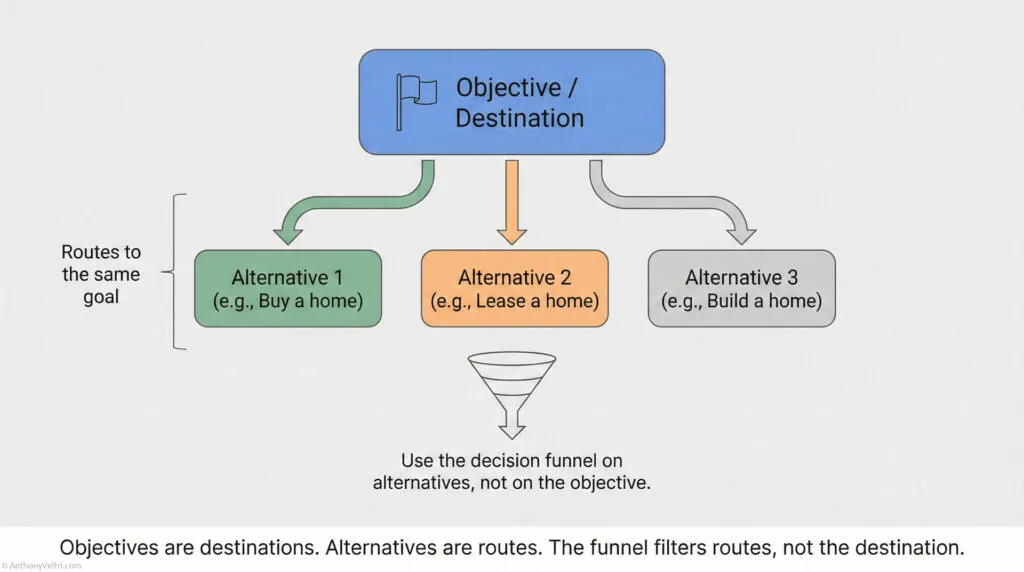

Pattern 25: Outcomes First, Alternatives Second #

(Government and operations version, there is one for private industry as well)

Most conflict in public work is either “we want different outcomes” or “we want the same outcome in different ways.” Calling it a personality issue makes it harder to fix.

Core Distinction #

1. Conflict over objectives (public outcome, end state)

People disagree about what success is.

Examples:

- During a wildfire, one group frames the objective as protecting communities and critical infrastructure, while another frames it as maximizing acres treated for long-term ecosystem health.

- In a permitting program, leadership wants maximum throughput and reduced backlog, while a compliance office prioritizes zero findings in audits, even if that slows processing.

That is an objective conflict. Different end states.

2. Conflict over alternatives (methods, tactics, implementation)

People agree on what success is, but disagree about how to get there.

Examples:

- Shared objective: “Reduce permit processing time without increasing error rate.”

- Alternative A: Reassign staff from inspections to help at intake.

- Alternative B: Introduce a triage queue and automation, keep inspectors in the field.

- Shared objective: “Maintain an accurate common operating picture for this incident.”

- Alternative A: One centralized incident GIS product everyone must use.

- Alternative B: Let each agency maintain its own system and publish into a shared view.

That is an alternative conflict. Same outcome, different routes.

Fast Diagnostic For Public Sector Context #

When a meeting gets tense, you can run this 3 step test:

- Can we state the outcome in one sentence we all agree on?

- If no, you have objective conflict.

- If yes, you probably have alternative conflict.

- If we temporarily freeze the outcome, what options are actually being debated?

- If people can clearly name competing options to reach the same outcome, it is about alternatives.

- Who has the authority to set the outcome here?

- Program manager, incident commander, agency lead, portfolio board, etc.

- If the answer is fuzzy or political, you have a decision rights problem on top.

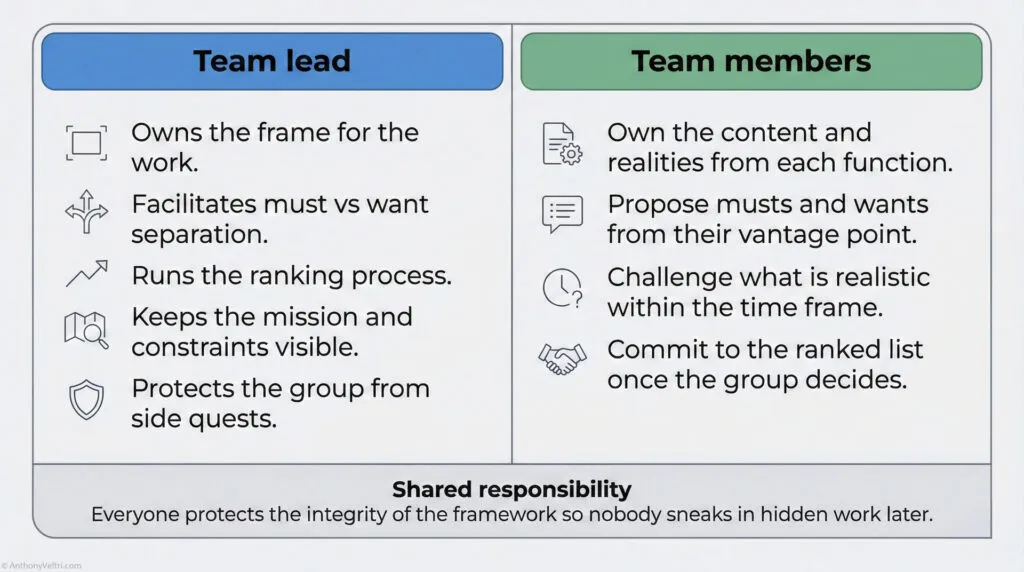

Move Set For Leaders In Public Operations #

A. When the conflict is about alternatives #

You keep the outcome fixed and open up the route.

- Anchor the shared outcome.

- “We agree the outcome is to cut average inspection wait time from 90 days to 30 days without increasing serious defects, correct?”

- Name the alternatives in plain language.

- “You are arguing for a dedicated surge team. You are arguing for process automation and reassigning part of existing staff.”

- Look for three kinds of resolution.

- Combine

- Example: Short term surge team plus parallel work to automate the top 20 percent of common cases.

- Sequence

- Example: Start with low risk automation for simple cases, then, once stable, consider shifting staffing.

- Third option

- Example: Pilot a joint “front counter” with another department rather than moving people permanently.

- Combine

- Keep it about public value, not personal worth.

- “We are not voting on whose approach is smarter. We are choosing the approach that best serves the outcome.”

B. When the conflict is about objectives #

You stop treating it as a planning argument and name it as a strategy and policy decision.

- Surface the competing objectives.

- “It sounds like half the room is optimizing for speed of service. The other half is optimizing for zero audit flags. Those are two different outcomes.”

- Clarify who sets the objective.

- “Under our charter and policy, who actually owns this call? Is it the department head, the portfolio steering group, or this program manager?”

- Let the decision owner set the outcome after hearing input.

- “We have heard the tradeoffs. As the program owner, I am setting the objective as: reduce the backlog by 50 percent in 12 months, with a hard cap on serious errors at current levels.”

- Reset the conversation to execution.

- “Now that the objective is set, our work in this group is to find the best combination of alternatives to hit it. We are not reopening the outcome every meeting unless the owner explicitly does so.”

- Kill the quiet non agreement pattern.

- The public sector version of “Gary” is the unit that nods in meetings, then slow rolls the work and later says, “Well, we never really agreed with that direction.”

- Your counter move:

- “If you have concerns with the objective, this is the time to raise them. Once the decision owner decides, our standard is that we execute professionally, even if it was not our preferred choice.”

Common Failure Modes This Pattern Targets #

- Policy fights disguised as process arguments.

- People argue about forms, systems, or staffing models when they actually disagree on who should be served first, what risks are acceptable, or what success means.

- Polite agreement, practical resistance.

- Everyone says “Yes, that makes sense” in the room, then behaves as if a different outcome was chosen.

- Personality story instead of structure story.

- “Legal and Operations just never get along.”

- That story hides the real issue: different outcomes, unclear decision rights, or unresolved tradeoffs.

- Decision by drift.

- No one wants to own the choice, so backlog, risk, or public frustration grows until something breaks and forces a decision.

4. Pattern Template (Paste Ready) #

Pattern Name

Problem:

Pattern:

Applies to:

Example:

Failure Mode:

Cross Links:

5. Cross Links to Entire Doctrine #

The Pattern Library supports:

- Annex A: Human Contracts

- Annex B: Data Contracts

- Annex C: Interface Ownership

- Annex D: Decision Altitudes

- Annex E: Prevention–Contingency Matrix

- All 20 Principles

Patterns are the connective tissue that make your doctrine actionable.

6. Doctrine Diagnostic – For Reflection: #

Begin recognizing the patterns in your daily work.

Where do you see:

- drift

- unclear ownership

- escalation chaos

- leadership thrash

- schema instability

- missing fallback

- over centralization

- unclear intent

Apply the pattern.

Normalize the solution.

Stabilize the system.

Last Updated on December 5, 2025