Stewardship vs. Optimization: Preserving What Cannot Be Allowed to Fail

Why mission-critical systems require stewards, not just managers #

Organizations optimize for efficiency. Leaders optimize for performance. Stewards optimize for preservation of mission-critical capability.

The distinction matters because stewardship and optimization often point in opposite directions. Stewardship accepts higher cost and lower efficiency to preserve what cannot be allowed to fail.

Stewardship answers two threshold questions:

Is it mission critical?

Can the mission survive if this fails?

Is it fungible?

Can we replace this capability easily if we lose it?

If the answer to either question is no, the capability requires stewardship.

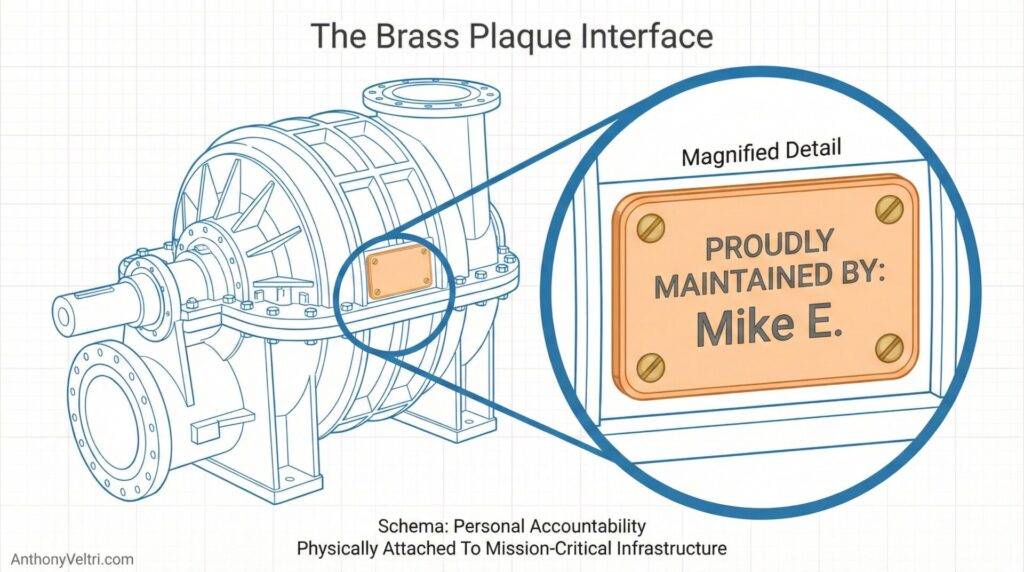

Lived Example: The Brass Plaque at Hoover Dam #

The brass plaque with a name means something fundamentally different than “Maintained by Facilities Department.” It represents personal accountability physically attached to mission-critical infrastructure.

You probably shouldn’t outsource your ability to swim to somebody else.

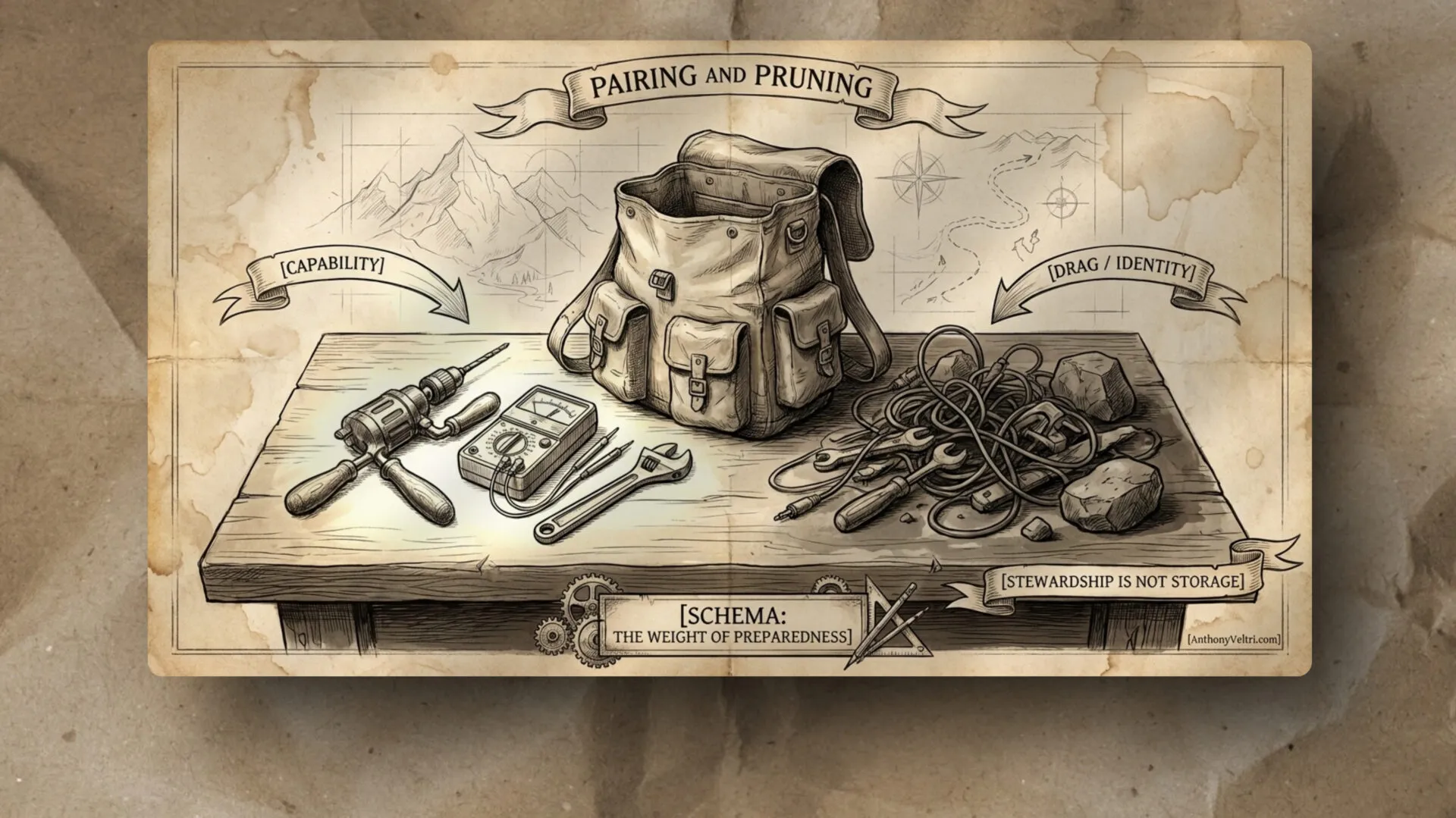

Stewardship vs Ownership: Time Horizon and Fungibility #

Anyone can own something. In a disposable society, most things are owned for disposal rather than protracted use.

If the organizations you interact with are ephemeral, there is no need for stewardship.

Seasonal businesses (Christmas trees, fireworks stands) may steward knowledge of how to sell, but they do not steward the things. They optimize for the season, dispose of inventory, and start fresh next year.

Stewardship requires three conditions:

- Non-fungibility: The capability cannot be easily replaced

- Criticality: The mission cannot survive without it

- Time horizon that extends beyond the current operator

“Saving it for the next guy” matters when you ARE the next guy.

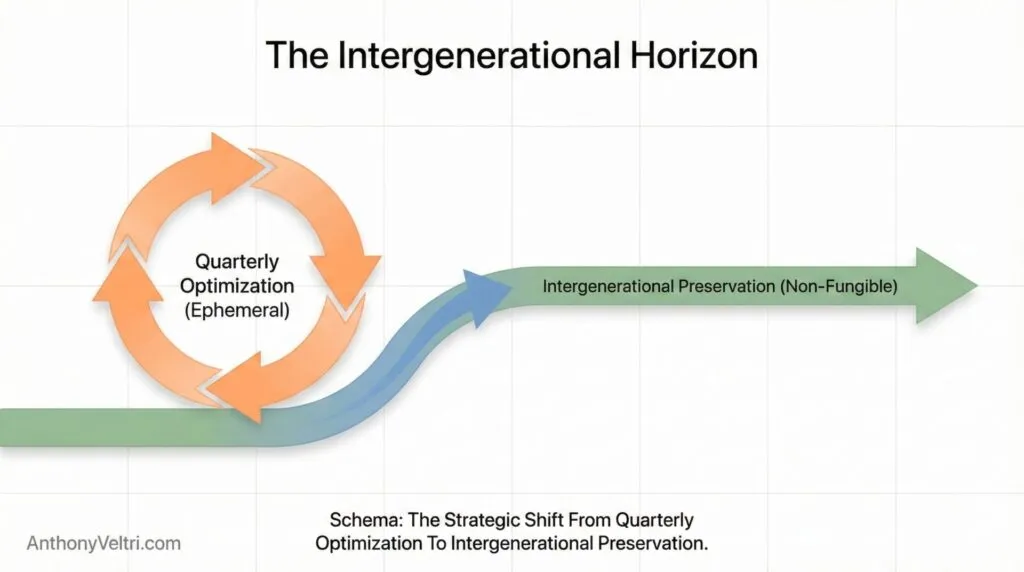

Business Terms: Intergenerational Thinking (Knowledge Continuity) vs Quarterly Optimization #

Organizations manage to different time horizons:

Quarterly/seasonal horizon:

- optimize for this quarter

- manage for this report

- efficiency over preservation

- can rob from the year to pay the quarter

Intergenerational horizon:

- manage for the heir who will inherit this

- cannot abdicate responsibility

- preservation over optimization

- cannot uninherit the consequences

The king who cannot abdicate the throne cannot live for a 4-year election cycle. The heir inherits the good AND the bad.

This is the stewardship threshold: Are you managing for things that cannot be uninherited?

System Terms: Self-Reliance When External Dependencies Fail #

In rural or isolated contexts, you cannot always count on a plumber or tradesman to be available. You have to be able to take care of things yourself.

The best way to take care of things is to not break them in the first place.

This is the “saving it for the next guy” principle. Often, you are the next guy.

If a machine breaks on the night shift, leaving it for the next guy to fix means leaving it for yourself.

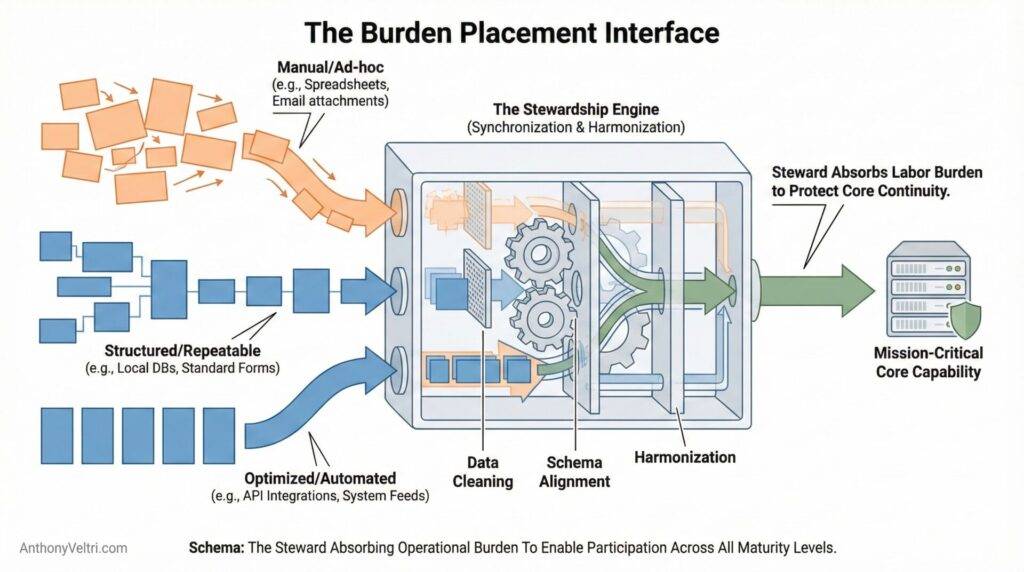

Business Terms: What Stewardship Costs and Enables #

Stewardship is more expensive than optimization:

- higher cost

- lower efficiency in the short term

- burden placed on the steward, not the parties

But it enables:

- sovereignty (capability independence)

- overcompliance protection

- mission continuity when systems fail

- participation across maturity levels

When parties bring something to a steward regardless of their capability level or maturity, the steward invests the time to handle it properly. This is the burden placement principle.

Steward’s Translation Layer. When a low-maturity office provides messy data, the Steward doesn’t send it back with a list of “Compliance Errors” (placing the burden on the party). The Steward cleans the data while providing the party with the template for next time. This is the “Burden” (doing the manual labor of harmonization to protect the Party’s tempo).

The alternative: Make each party responsible for their own capability maturity. This is efficient. It also creates barriers that prevent less-mature entities from participating. Federation collapses into exclusion.

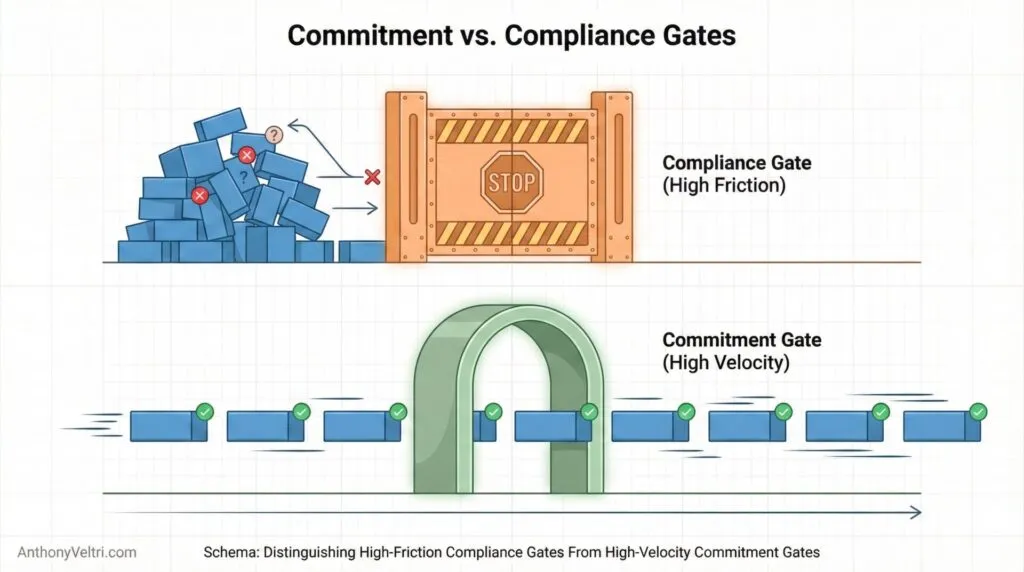

System Terms: Commitment Gates vs Compliance Gates #

Compliance gate:

- almost zero cost for admission

- high friction every time you pass through

- requires verification, documentation, approval each time

- optimizes for control

Commitment gate:

- higher price of admission (building trust, establishing patterns)

- near-zero friction once admitted

- operates on internalized standards

- optimizes for velocity

Stewardship enables commitment gates. By investing in capability-building and trust establishment, the steward reduces friction for future interactions. Most tasks operate through commitment gates. Only the most critical require compliance gates.

Without stewardship, everything defaults to compliance gates. Efficiency in verification, inefficiency in execution.

Detecting When Stewardship Is Missing #

Early warning signs that something mission-critical is being treated as just another managed resource:

Time Horizon Contraction #

- managing for this quarter instead of next decade

- optimizing for this report instead of mission continuity

- efficiency metrics replace preservation metrics

Optimization Replacing Preservation #

- backup capacity repurposed for operational use

- emergency capacity multipurposed for routine work

- inherited capability traded for short-term gain

Things That Cannot Be Uninherited Being Treated as Disposable #

- infrastructure with no replacement path

- expertise with no succession plan

- interfaces with no ownership continuity

When you start managing for efficiency and optimization instead of intergenerational pass down, stewardship has been lost.

Why Organizations Fail at Stewardship #

The Multipurpose Failure Mode #

Organizations see dedicated capacity as underutilized capacity and multipurpose it for routine work.

The circus safety net was never meant to be used. It existed for emergency only. The old climbing maxim was “the leader must not fall” because hemp ropes would snap.

Strike Teams are organizational safety nets. They exist for mission-critical response when primary capacity fails.

The failure mode: Managers multipurpose Strike Teams for routine work because they appear underutilized.

This is like using a fire extinguisher to wash car tires. Yes, it pressurizes water. Yes, it could do this. But now the extinguisher needs recharging and maintenance.

What happens when emergency capacity is multipurposed:

- distraction from mission focus

- capacity exhaustion

- mission cheapening (routine work displaces critical work)

- degraded emergency response when actually needed

Choosing not to build in-house is often an act of stewardship for the Strike Team’s limited capacity. Protecting them from being consumed by work that should be handled through other mechanisms.

Some things you just don’t want to multipurpose.

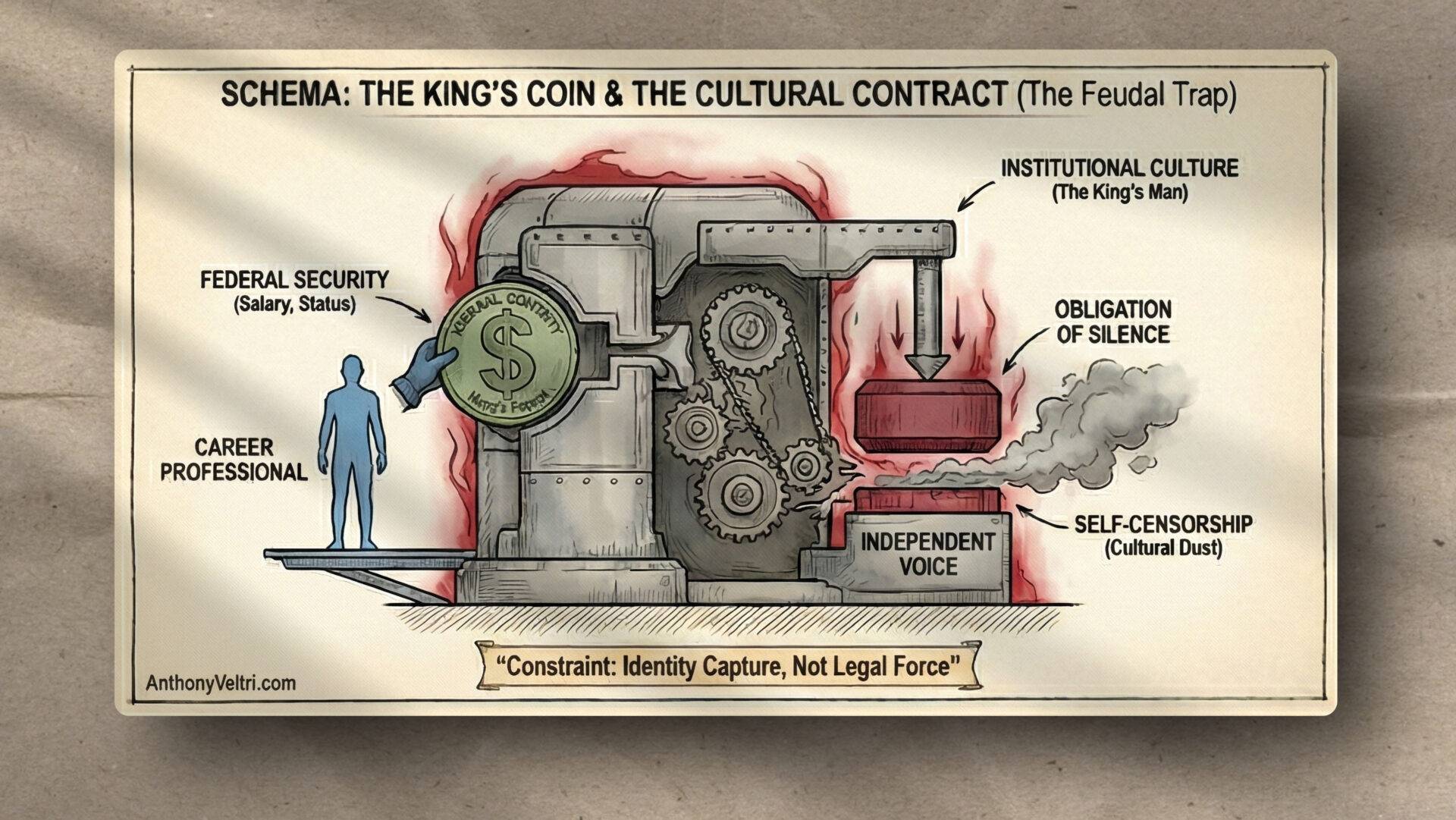

When Optimization Kills Stewardship #

Failure Pattern: Process as Solution to Culture #

The U.S. Forest Service’s Yellow Card Safety Empowerment program (launched 2010-2011, still in official use today) addresses a real problem: temporary and seasonal employees who felt they couldn’t challenge unsafe conditions because they thought they were competing for permanent positions.

The optimization solution: Issue yellow cards that employees can present to any supervisor to stop unsafe work without repercussions. The card grants explicit permission to halt operations when safety is at risk.

The optimization thinking: We need a measurable, trackable safety initiative that empowers employees (other organizations may call this Stop-Work Authority or Safety Authorization in lieu of “empowerment”).

What the card has accomplished: The program has likely prevented incidents. When employees have used the card as intended, work has stopped and hazards have been addressed. Any single person protected by this intervention represents a success worth celebrating.

How the program is celebrated: The yellow card is enshrined in the 2024 Master Agreement between the Forest Service and its union. It’s official policy. Managers are required to print and distribute cards annually. The program is presented as a safety achievement, a demonstration of the agency’s commitment to employee empowerment.

What very few recognize: The card’s existence reveals the problem it was designed to solve still exists.

What the card reveals: If you need a physical talisman to grant you permission to say something is unsafe, you have a broken culture. The card is a process solution to a stewardship problem.

The yellow card addresses the symptom (employees afraid to speak up) without addressing the cause: a structural hiring system that creates perverse incentives.

The structural problem:

Temporary and seasonal employees don’t just feel expendable. They are competing for permanent positions through a system with no direct ascension path.

How federal hiring actually works:

Temporary work may count as experience for a full-time position, but there are generally no direct conversion paths. Temporary employees cannot apply for slots reserved only for current temporary workers, because most vacancies are open to a wider applicant pool. They return to the same applicant pool as everyone else, where they will be evaluated like everyone else.

They are hoping their good work gives them a unique advantage. It rarely does.

The rational response to a broken system:

Temporary employees take risks to prove they deserve permanent positions. They work harder. They complain less. They accept dangerous assignments. They don’t challenge supervisors.

This is not irrational behavior. This is the rational response to a system where:

- performance is visible

- hiring pathways are opaque

- standing out might help

- formal credentials matter more than field performance

The absurdity of the hope:

This would be equivalent to dressing in a suit and tie and waiting outside an investment bank, hoping that’s how you get hired.

Or showing up at an NFL combine practice field in full gear, hoping they’ll let you in because you look the part.

If your name’s not on the list, you’re not getting in. Performance in the field doesn’t cut you to the front of the hiring line.

What the card doesn’t fix:

The card gives employees permission to refuse unsafe work without repercussions.

It does not create pathways from temporary to permanent employment.

It does not eliminate the incentive to take risks to stand out.

It does not change the fact that temporary employees are competing for positions through a system that largely ignores their field performance.

The optimization trap:

The agency optimized for a safety mechanism (the card) without addressing the employment structure that creates the safety problem. The card treats the symptom. The hiring structure is the disease.

It’s like celebrating a Band-Aid over a wound that needs debridement. The surface is covered. The underlying infection remains.

The optimization paradox:

- Metric: Cards distributed, cards used, incidents prevented

- Reality: Need for cards persists across decades

- Success: Employees feel safe pulling the card

- Failure: Employees still need the card to feel safe

The card creates a procedural bypass around the cultural problem. It does not fix the cultural problem.

The stewardship gap:

In a healthy safety culture, the card would become unnecessary. Employees would challenge unsafe conditions without needing explicit permission. Supervisors would invite challenge without requiring a formal mechanism.

The card’s continued necessity, decades after implementation, indicates the underlying stewardship failure persists. The process works. The culture hasn’t changed.

Stewardship would look like: Field supervisors thinking “I need to look out for these people. I do not want them getting hurt because they think they’re going to impress me.” Not: “We have a card for that.”

Failure Pattern: Optimizing Emergency Capacity #

A manager optimized data storage by repurposing backup drives for operational use. This improved storage utilization metrics.

The problem: When field teams needed working copies for offline use, no backups existed. They had to take primary systems offline or create workarounds.

What happened: She improved metrics in one area (storage utilization) at the expense of metrics she wasn’t measuring (operational continuity, field team productivity).

The stewardship failure: Backups exist to protect mission capability when primary systems fail. Optimizing them away treated emergency capacity as inefficient rather than essential.

The Hoarding Trap: Distinguishing Stewardship from Gatekeeping #

The failure mode: People claim “stewardship” when they’re really gatekeeping.

“We can’t give you access to this data. We only have one copy. We are the stewards of the data, so you’ll have to wait.”

(Translation: We repurposed the other copies for our own projects, and now we’re using “stewardship” language to justify not sharing.)

How to Distinguish Stewardship from Hoarding #

Stewardship:

- invests in capability-building so others can participate

- enables sovereignty

- distributes capability while protecting critical infrastructure

Hoarding:

- concentrates control

- creates dependency

- uses scarcity to justify gatekeeping

The Handoff Problem: Hero Stewards as Single Points of Failure #

The brass plaque says “Mike E.” What happens when Mike retires?

Many organizations have zero overlap between departing and arriving personnel due to HR rules: cannot hire a replacement until the position is vacated.

Two weeks of overlap is exceptional. One week is rare.

Some knowledge cannot transfer in a week. Maintaining 70-year-old alternators at Hoover Dam is not something you can hand off in a brief transition period.

The hero steward pattern is a single point of failure.

The Transition Must Be Celebrated, Not Just Processed #

The departing steward must not feel they are losing their identity or agency. This is a graduation.

Organizations that treat stewardship transitions as mere HR events rather than knowledge continuity events create recurring handoff failures.

Society celebrates these transitions less than it did in the past. This is a structural vulnerability.

The “Continuity Log.” is a concept to explore: A Steward doesn’t just hand off a password; they hand off a record of the why behind the architecture. If HR rules prevent overlap, the “Stewardship Burden” includes the creation of a High-Fidelity Archive that allows the “Next Guy” to step in without a 6-month learning curve.

The Malicious Incompetence Trap: When Non-Stewards Exploit Stewards #

A second failure mode emerges when some parties recognize they can offload work onto stewards by producing substandard output or simply waiting.

The pattern: Organizations with data stewards, interface stewards, or quality stewards create an unintentional incentive structure. Non-stewards learn that if they produce low-quality work or incomplete deliverables, the steward will invest the time to bring it up to standard.

Example: Data stewardship exploitation

A data steward is responsible for ensuring datasets meet quality standards before integration. Teams learn that submitting rough, poorly-documented data is faster than doing it properly. The steward will clean it up anyway.

What happens:

- steward workload increases exponentially

- teams stop investing in quality

- steward becomes bottleneck

- “stewardship” becomes servant work rather than capability building

How to distinguish stewardship from exploitation:

Stewardship:

- invests in teaching parties how to meet standards

- raises capability over time

- parties improve quality of submissions

- steward workload decreases as parties mature

Exploitation:

- parties submit progressively lower quality work

- steward does the work for them

- no capability transfer occurs

- steward workload increases over time

- parties become dependent rather than sovereign

Active Stewardship vs. Passive Service: A Steward is not a “Butler” who cleans up quietly. A Steward is an Architect who says: “I handled this for you today to keep the mission moving, but here is the pattern you must follow for next Tuesday.

The steward’s role is to shape contributions so they meet standards, not to do the work for parties who could do it themselves but choose not to.

CRUCIAL DISTINCTION: WEAPONIZED COMPLIANCE: It is vital to recognize that “malicious incompetence” is rarely overt failure; it often manifests as sophisticated, weaponized compliance.

In this scenario, the partner exploits the gap between tacit understanding and explicit instruction. They refuse to interpret the intent of a mission, forcing the Steward to explicitly define every single parameter of a task before they will act.

By prioritizing “avoiding doing the wrong thing” (compliance) over “doing the right thing” (contribution), they successfully shift the entire cognitive burden of task definition back onto the Steward while remaining protected by the letter of the rules. The Steward falls into the trap by accepting technical compliance as a substitute for genuine capability.

Interface Stewardship: Why Interfaces Require Special Treatment #

Systems can be owned. Most things break at interfaces, not within systems themselves.

Interfaces that do not have owners at both ends are especially prone to failure.

The interface requires a steward to connect those owners.

Owners of interfaces generally come with:

- different maturity levels

- different capacity levels

- different organizational priorities

The steward performs synchronization and harmonization to ensure:

- each party gets what they need

- each party can provide what they must

This is why interfaces get special treatment. Not because other things would not benefit from stewardship, but because interfaces are especially prone to failure when coordination responsibility is unclear.

Can Stewardship Be Distributed? #

Yes. This goes back to Commitment over Compliance.

In a compliance-based organization: “Don’t step on Sergeant Major’s lawn. Police your dang gone candy wrappers, trooper.”

In a commitment-based organization: People do not want to see their area dirty. Not only because they know it will bring consequences, but because they care about the space.

Everybody is a steward. Not just the designated role.

The Difference Between Babysitting and Stewardship #

Babysitting/Butler model:

- steward acts as domestic servant

- everyone else acts as hotel guests

- guests responsible only for showing up and paying

- guests contribute nothing

Stewardship model:

- everyone contributes

- participation at capability level

- shared responsibility for outcomes

In a home, people contribute. In a hotel, people consume.

Organizations scale the same way.

Stewardship at Scale: Distribution, Not Concentration #

As organizations scale from small offices to larger entities, people become incentivized for different things:

- preserving the mission

- ensuring organizational longevity

- optimizing for the quarter

- optimizing for the week

- optimizing for the next report

Where these time horizons conflict, it becomes easy to rob from the year or the decade to pay the quarter or the week.

Dunbar’s Number Applies to Stewardship #

Beyond a certain organizational size, a single steward becomes a functionary title rather than an actual role.

You need multiple stewards operating at appropriate scale.

A “NATO Steward” or “Forest Service Steward” at enterprise scale is a coordination role, not an operational stewardship role.

Effective stewardship at scale requires:

- stewards at appropriate span of control

- clear domains of stewardship responsibility

- coordination mechanisms between stewards

- escalation paths for cross-domain issues

What Stewardship Enables #

When stewardship is done right:

Work Products Fit Through Production Gates #

The steward shapes contributions so they meet standards, regardless of source maturity level.

People Develop Toward Commitment Gates #

Stakeholders internalize standards rather than requiring verification each time.

Mission-Critical Capability Is Preserved #

The things that cannot be allowed to fail have names attached and capacity dedicated.

Sovereignty Is Protected #

Entities can participate at their maturity level without being excluded or forced into premature standardization.

Culture Shifts from Compliance to Commitment #

Permanent supervisors think “I need to protect these people” not “we need process to prevent liability.”

Mission Continuity Extends Beyond Any Individual Operator #

The knowledge, capability, and accountability transfer successfully to the next generation.

Stress Testing the Principle #

When stewardship is introduced into an efficiency-driven organization, it creates specific friction points. These are not signs of failure: they are diagnostic signals that the system is shifting from a disposal mindset to a preservation mindset.

Friction Point 1: The “Single Point of Failure” (SPOF) Risk #

The Reader’s Thought: “If the mission depends on ‘Mike E’ and Mike is unavailable, the system fails. This is the opposite of a robust, redundant architecture.”

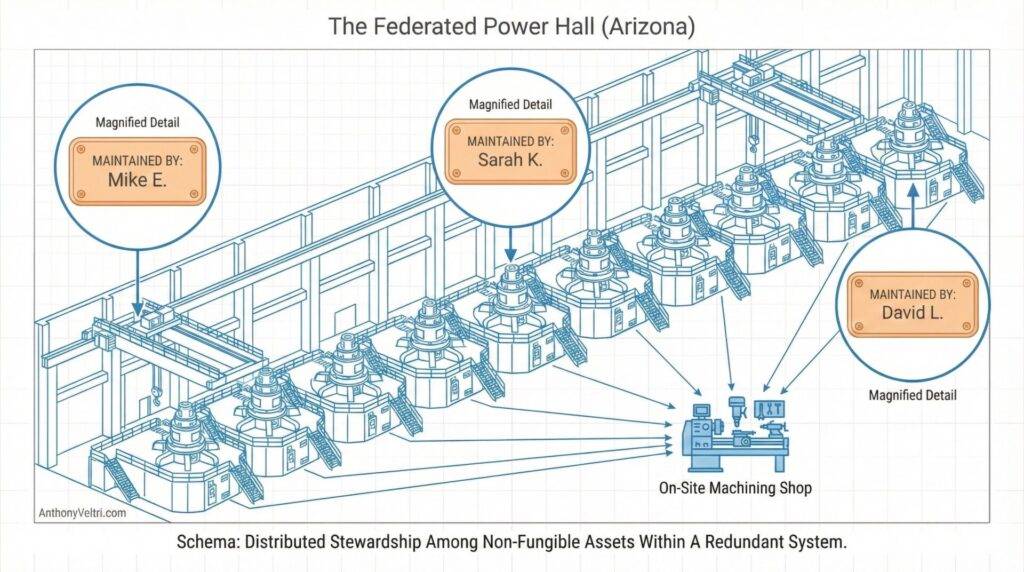

The Architecture: In the power generation halls of Hoover Dam, there are 17 main generators (9 on the Arizona side and 8 on the Nevada side). Mike E’s name is on one specific unit: other names are on the others. This is Distributed Stewardship.

While every technician possesses the fungible skills to maintain any unit in the hall (the fallback), the brass plaque ensures that every specific machine has a primary advocate. Stewardship is the remedy for the “tragedy of the commons”: it ensures that “everyone’s responsibility” does not become “no one’s responsibility.”

The “Mike E” model provides a Point of Accountability that prevents maintenance drift, while the on-site machining shop provides the Shared Capability that ensures the system survives the loss of any single individual. The brass plaque is the interface for Pride of Ownership: the machining shop is the interface for Mission Continuity.

Friction Point 2: The “Capacity Exhaustion” Concern #

The Reader’s Thought: “We manage five hundred SharePoint sites. We cannot afford a named steward for every digital resource in the enterprise.”

The Architecture: Stewardship is a high-cost strategy reserved for Non-Fungible and Critical capabilities. If a site is fungible (a standard team collaboration space), it should be managed for efficiency and disposal. If the site is the mission-critical interface (the single source of truth for a high-value portfolio), it requires a steward. You do not steward the grass on the lawn: you steward the foundation of the building.

Friction Point 3: The “Gatekeeping” Accusation #

The Reader’s Thought: “This is just giving a single person the power to say ‘No’ and labeling it as preservation.”

The Architecture: We distinguish between stewardship and gatekeeping via the Commitment Gate. A Gatekeeper optimizes for control: they want to verify your credentials every time you pass through (Compliance). A Steward optimizes for Mission Tempo: they invest the time to train you and establish shared patterns so they never have to verify you again (Commitment).

The Steward’s goal is to turn a “Party” into a “Peer.” Gatekeeping creates dependency: Stewardship enables sovereignty.

The Core Principle #

Stewardship is the organizational commitment that the mission outlives the operator.

The brass plaque on the generator is not decoration. It is accountability that cannot be abdicated, responsibility that cannot be uninherited, and capability that cannot be allowed to fail.

Stewardship accepts the burden so the mission endures.

Last Updated on February 22, 2026