This guide defines “Truth as a Product.” It argues that data must be owned, scoped, and contracted, not just stored.

This page is a Doctrine Guide. It shows how to apply one principle from the Doctrine in real systems and real constraints. Use it as a reference when you are making decisions, designing workflows, or repairing things that broke under pressure.

Every complex system eventually trips over the same problem.

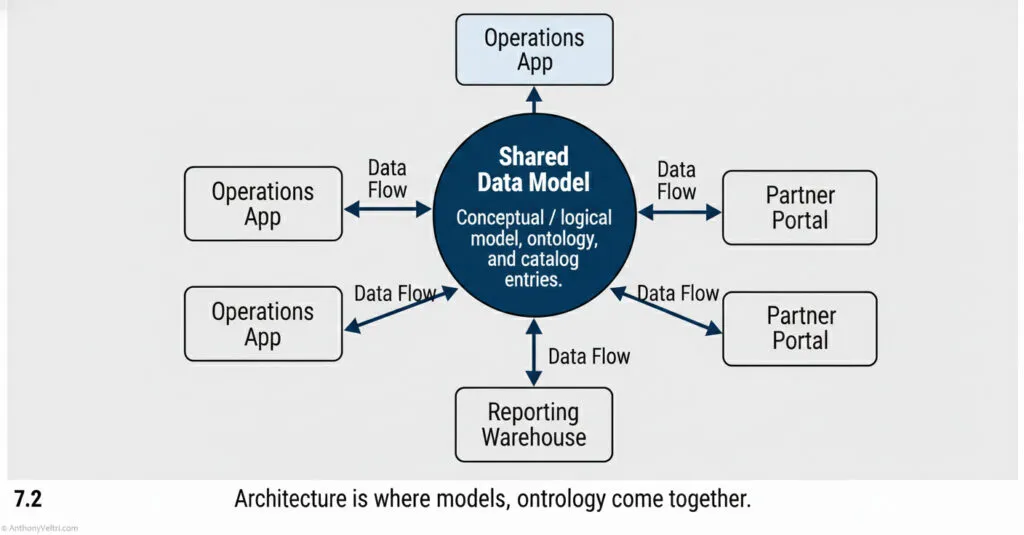

Different teams build different tools. Each tool has its own database. They all describe overlapping pieces of reality. At some point leadership asks a simple question, and five reports come back with five different answers.

At that moment, someone says “we need a single source of truth.”

Sometimes what they really need is a golden dataset.

A golden dataset is not a magic database in the sky. It is a deliberately curated representation of a specific slice of reality that your organization agrees to treat as authoritative for a defined purpose.

It is the place where truth is supposed to live for that domain.

It is also work. Real work.

Exhaust Versus Product #

Most organizations treat data as exhaust.

Applications generate data as a side effect of doing things. Logs pile up. Tables grow. Spreadsheets multiply on shared drives. People export, copy, transform and forget.

If you ask “who owns this data,” you get a list of application names or vendor logos instead of a human being.

Golden datasets flip that relationship.

Data is the product. Applications are just clients.

You are no longer saying “whatever lives inside this tool is the truth.” You are saying “this curated structure, with this schema, this lineage, and this stewardship, is our truth for this domain.”

That difference sounds subtle. It is not.

With exhaust, nobody is clearly accountable for quality. With product, someone is.

What Makes A Dataset “Golden” #

A golden dataset is not just the biggest pile of data. It has a few specific properties.

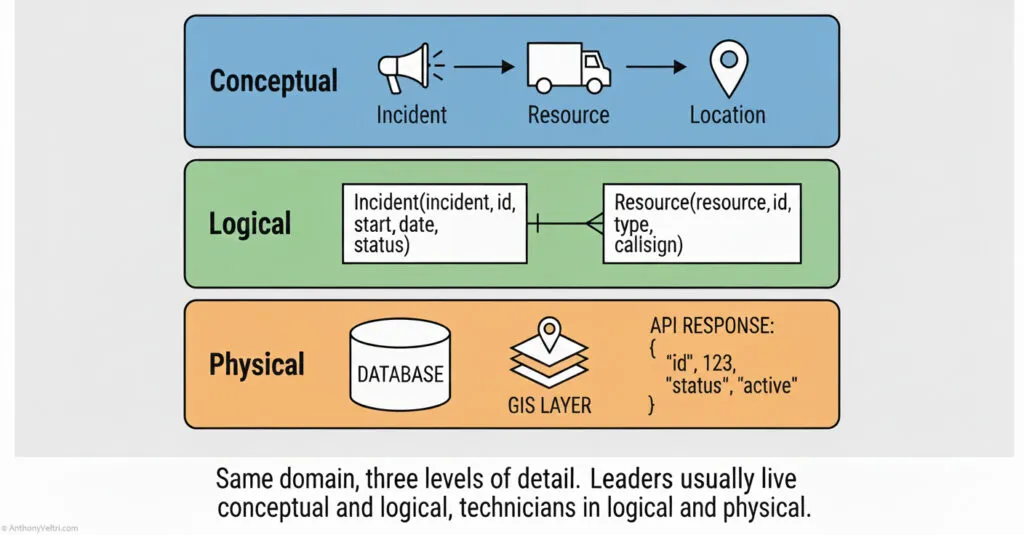

- Clear scope.

You can describe in one sentence what it represents. For example, “active wildland fire incidents in the United States,” or “approved critical infrastructure sites for iCAV display.” - Declared owner.

There is a named team or role that is responsible for the quality, evolution and availability of the dataset. Not just “IT.” - Published contract.

There is a schema, a set of definitions and rules about what each field means, how it can change and how often it is updated. - Known sources and lineage.

You can trace where the data comes from, how it is transformed and where it goes. There are no mysterious columns that “just showed up” one day. - Real consumers.

People and systems actually use it to make decisions. If nobody reads it, it is not golden. It is just tidy.

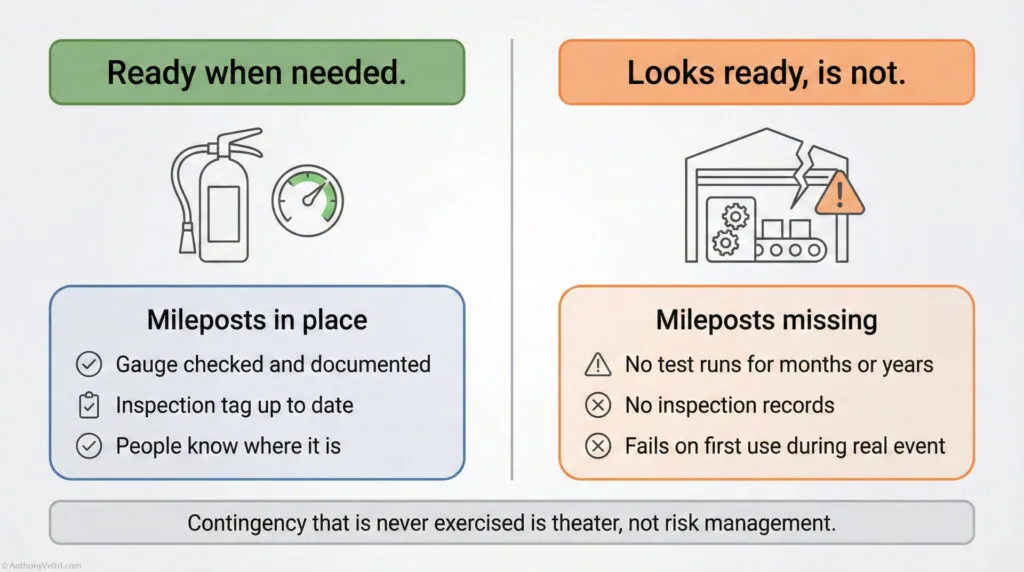

A golden dataset is not perfect. It has errors. It has lag. It has gaps. The difference is that those imperfections are visible and someone is on the hook to improve them over time.

iCAV And The Case For Golden Views #

In the iCAV world, we were halfway to golden datasets without using the phrase.

We pulled data from many partners about the 19 critical infrastructure and key resource sectors at the time. Some partners refreshed regularly. Others sent DVDs. Some had meticulously maintained GIS layers. Others had shapefiles that felt like archaeological artifacts.

We could not force everyone into a single master database. Sovereignty and uneven maturity made that impossible.

What we could do was define specific slices of the federated data that functioned as golden views for certain users.

For example:

- A curated layer of infrastructure sites that had passed basic validation.

- A set of incident records that met agreed criteria for display to senior leadership.

- Aggregated overlays that summarized risk without exposing all raw partner data.

Behind the scenes, we accepted that the underlying federation was messy. On the map, we offered decision makers a clearer spine to reason about.

A true golden dataset would have pushed that further. It would have:

- Named an owner for each slice, not just “the iCAV team.”

- Written down the rules for what made a site or incident “display worthy.”

- Published those rules back to partners so they could align their own feeds.

Even without the full structure, we saw the value. Every time we could say “this is the list we trust for this purpose,” arguments shifted from “which list is right” to “what do we do about it.”

That is the real point.

Golden datasets do not erase politics or uncertainty. They remove one level of noise so that the harder conversations can happen.

Wildland Fire, IRWIN, And Duplicate LIDAR #

The wildland fire community learned this same lesson the hard way.

It is easy to imagine each agency keeping its own incident records completely separate. Forest Service, BLM, Park Service, states, tribes. Each with its own tool, its own codes, its own history.

In practice, that breaks the mission. Aviation safety, resource ordering and interagency coordination all depend on everyone looking at the same core picture of where incidents are, what they are called and how they are evolving.

Systems like IRWIN exist because someone decided that “incident record” is a domain that deserves a golden dataset.

That does not mean every bit of fire related data is unified. It means there is an authoritative backbone for incident identity and status that others can hang from.

Contrast that with your LIDAR story.

Multiple parts of the same organization flew overlapping LIDAR over the same terrain. Regions. Ranger districts. National program offices. Grants. They were not talking to each other. Each set was “true” in its own narrow context. Together they formed a wasteful, fragmented picture.

On fires, those same players voluntarily coordinate around shared aviation and data standards. They know they cannot afford three versions of where the aircraft is or what the fire perimeter looks like.

What changed is not just technology. It is the decision to treat some domains as deserving of golden treatment and others as “everyone does their own thing.”

Golden datasets are not primarily about storage. They are about where you decide duplication is acceptable and where it is dangerous.

Where Golden Datasets Go Wrong #

There are failure modes too.

- Golden in name only.

A team declares their database “the golden source” but does nothing to improve governance or quality. Nobody agrees. Everyone carries on with their own copies. - Too broad a scope.

Someone tries to create a golden dataset for “all data about operations,” which is too vague to manage. The effort collapses under its own ambition. - No visible consumers.

A beautiful, well documented dataset is built, then nobody uses it because it was not aligned to any real decisions. It quietly decays. - Hidden coupling.

A golden dataset is used in so many places that changing it becomes impossible. People start taking copies to protect themselves from breakage. You are back where you started, but with extra ceremony.

These are not arguments against golden datasets. They are reminders that calling something “golden” does not make it so.

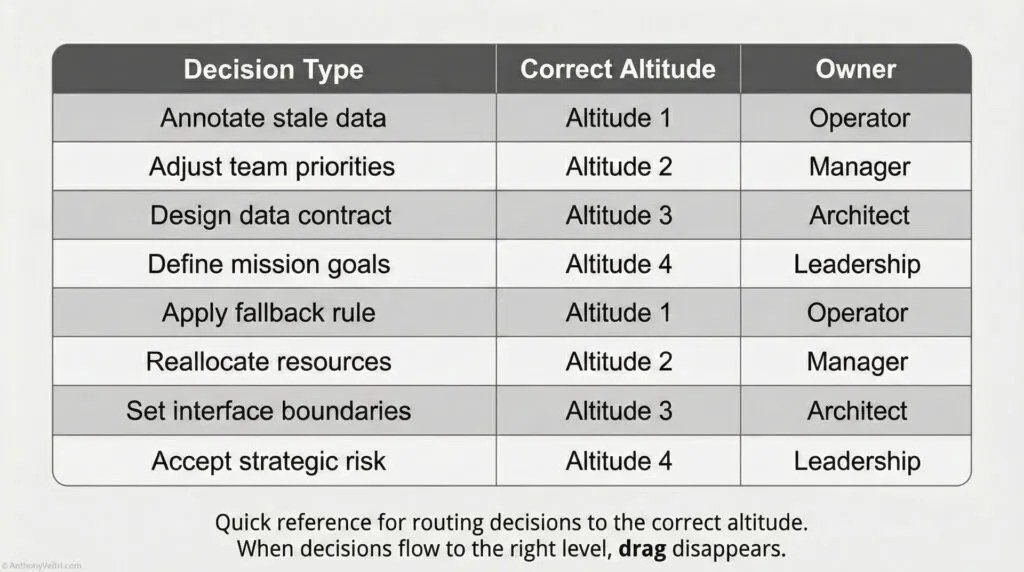

How To Decide What Deserves Golden Treatment #

You cannot turn everything into a golden dataset. Nor should you.

The litmus test I use is simple.

Ask:

- Where are we repeatedly reconciling different answers to the same question

- Where do disagreements about “what is true” slow down important decisions

- Where do we pay real money or risk because duplicated effort and confusion are normal

If the same domain keeps lighting up, that is a candidate.

In many organizations, obvious candidates include:

- Customers or partners

- Assets and infrastructure

- Incidents or cases

- Key performance metrics that drive funding and accountability

Examples from my world:

- Critical infrastructure and incident views in iCAV.

- Wildland incident records in IRWIN.

- Resource ordering in ROSS.

- Reader: what are some examples from your world?

Once you have considered this, ask one more question:

- Who will own this, not as a side job, but as a product

If you cannot name that person or team, you are not ready.

Doctrine: Treat Truth As A Product, Not An Accident #

Golden datasets are a discipline.

They require you to:

- Admit that not all systems are equal. Some deserve to be clients, some deserve to be the spine.

- Name owners who will shepherd the data over time, not just during the initial project.

- Live with the discomfort of choosing a single authoritative view when you know reality is always more complicated.

The payoff is that, in the domains you choose, you stop burning attention on “which version” and start spending it on “what now.”

In a world of federated systems, human sovereignty, overlapping missions and messy politics, that is about as much truth as you can hope to centralize.

Not everything should be golden.

What you deliberately choose to make golden should be treated as a real product, owned and cared for, not as exhaust that just happened to land in one place.

Last Updated on February 22, 2026