How Wildland Fire Actually Moves: A Guide To The Three Tier Dispatch System

When people picture wildland fire, they usually see flames, aircraft, and line gear.

What they do not see is the invisible network that moves people and aircraft to the right place at the right time.

In the United States, that network is a three-level (tier*) dispatch and coordination system:

- Local dispatch centers

- Geographic Area Coordination Centers

- The National Interagency Coordination Center at NIFC in Boise

Terminology Collision: “Tier” and “Type” are easy to invert

Some wildfire references label NICC as Tier 1 and local dispatch as Tier 3, while other explainers describe local dispatch as the first level of response. Because “tier” is overloaded and often inverted, I will name these levels by scope instead: local, geographic area, national.

This is not just a wildfire quirk. Different communities reuse simple labels for different dimensions. In IT support, “Tier 1” usually means first-contact support and escalation goes upward. In NIMS/ICS, “Type 1” is often the highest capability. I’m not claiming these systems are the same. I’m pointing out that the labels are inconsistent, so I’ll map by dimension instead.

Mapping move: Harmonize without tier numbers

When you are mapping across federated entities, treat “tier” as a dangerous label and map by the underlying dimension:

Designation / prioritization: Tier 1 vs Tier 2 assets (critical infrastructure programs)

Scope: local vs geographic area vs national

Escalation: first contact vs specialist vs expert

Capability: higher vs lower capability (example: NIMS/ICS “Type 1/2/3”)

If you work in tech or national security, this structure feels familiar. It is one of the cleanest real world examples of federated coordination that still delivers a coherent national picture.

This guide is my attempt to explain how it works in plain language, and how it shaped my own doctrine.

Along the way, I want to highlight one specific role inside this system that lives very close to modern air command and control work.

The lead plane pilot.

Taking Flight: A Lead Plane Pilot’s View

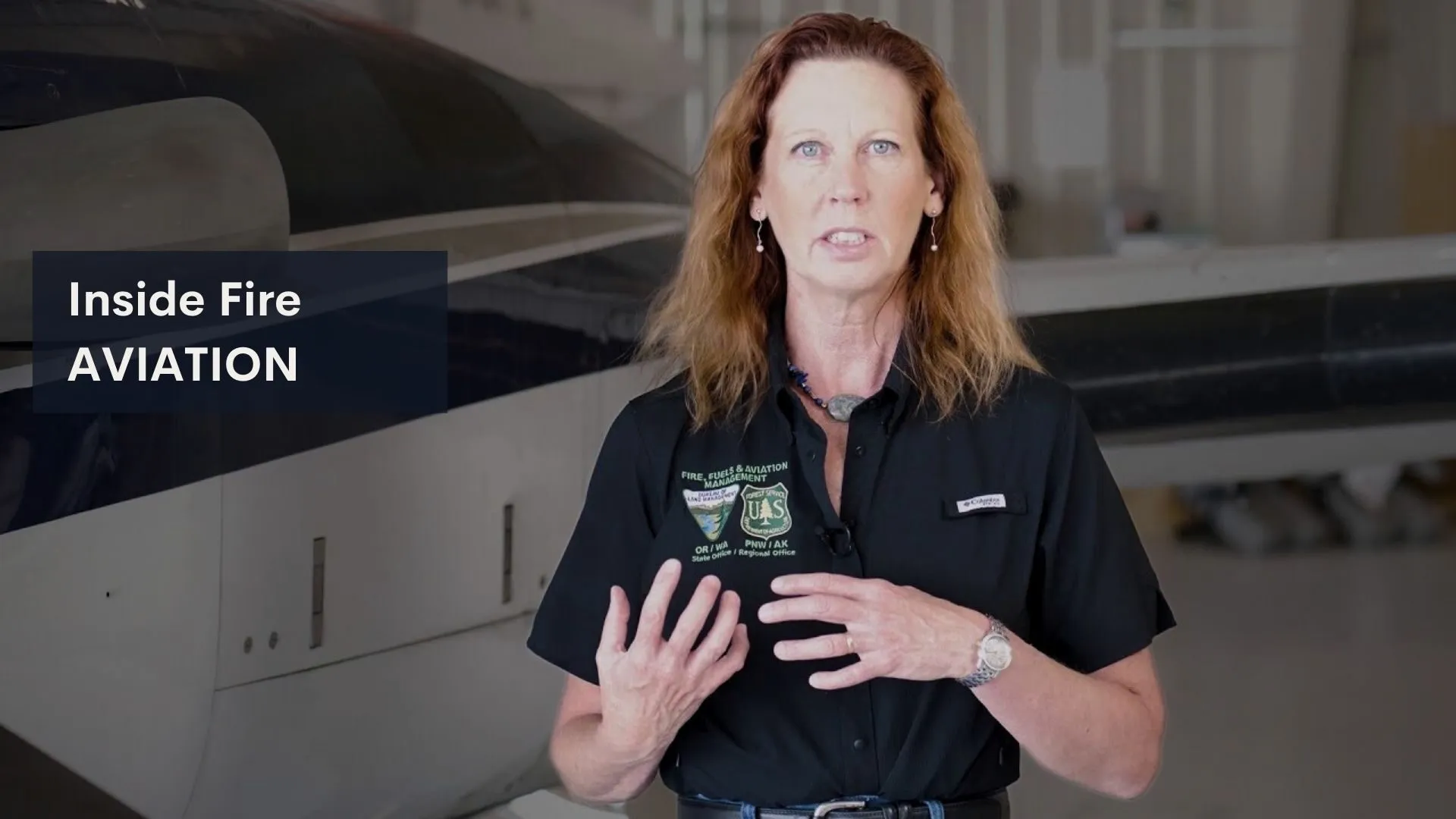

I had the privilege of interviewing Mary Verry, a fixed-wing program manager and lead plane pilot for the U.S. Forest Service, and of producing the public video that came out of that interview.

Originally published by the U S Forest Service on YouTube. Watch or share their version here.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HmdTQyq3jFU

“My name is Mary Verry and I’m a pilot for the U.S. Forest Service.

I’ve been with the Forest Service just shy of 21 years.

My current title is Fixed Wing Program Manager for the Pacific Northwest and Alaska.”

Her territory on paper is Washington, Oregon, and Alaska.

In reality, in her role as a lead plane pilot, she can be sent anywhere in the country:

“We go nationwide from Alaska all the way down to Florida, and everywhere in between.”

What she said next gets at the core pattern I want to underline.

“Aviation, in and of itself, is a support organization.

We’re always supporting something or somebody.”

In the Forest Service firefighting world that means:

- The lead plane supports the air tankers

- The air tankers support the ground firefighters

- The whole aviation stack supports the incident objectives that are set on the ground

Everything is nested support. No aircraft exists as a solo hero.

What A Lead Plane Actually Does

Mary’s summary of the lead plane role is deceptively simple.

“A lead plane is simply an aircraft, such as this King Air, that finds escape routes for the retardant airplanes, or the fire bombers.

We go in first, we find the escape route.

We support them and we’re there for their safety.”

That sounds basic until you imagine the environment:

- Mountainous terrain

- Variable winds

- Smoke that hides ridgelines and powerlines

- Multiple aircraft stacked in a Temporary Flight Restriction

- Ground crews maneuvering under that same airspace

In practice, the lead plane pilot:

- Enters the fire traffic area ahead of the tanker

- Confirms terrain, winds, and hazards

- Coordinates with ground resources on drop locations and sequencing

- Demonstrates the run so tankers can fly it safely and repeatably

- Maintains a mental model of escape routes if something goes wrong

On paper, you could imagine “saving money” by sending tankers without a lead plane.

In reality, the lead plane is the human interface between doctrine, the National Airspace System, and the chaotic reality of smoke, terrain, radio congestion, and human fatigue.

That is air command and control in miniature.

The Three Level Dispatch System: How Fire Actually Moves

Mary’s aircraft does not launch in a vacuum. It is plugged into a three level dispatch system that quietly coordinates tens of thousands of fires and movements every year.

Local Dispatch, Where Fire Actually Starts

Every wildland fire begins as a local problem.

A lightning strike. A downed power line. A campfire that got away.

The first people to act are usually routed through a local dispatch center. Depending on whether you count all local dispatch offices or only interagency dispatch centers, you’ll see figures like 200+ or 250+ local dispatch centers nationwide.

From the perspective of a local dispatch center:

- They take the initial report

- They send the closest engines, crews, and aircraft

- They track resources as they arrive, work, and return to base

- They juggle multiple incidents at once during busy periods

If they have enough people and aircraft to handle things, it stays local.

If they do not, they ask for help.

The important pattern here is closest forces plus local context. The local center knows:

- Who has been on the line for 14 hours and needs rest

- Which helicopter has maintenance coming due

- Which roads are washed out and which are barely passable

In my doctrine language, local dispatch is where clear intent and degraded operations live in the same room. The picture is messy and incomplete, but decisions cannot wait.

Geographic Area Coordination Centers

When fire activity outgrows what local dispatch can handle, resource requests escalate to the next tier.

The United States is divided into 10 geographic areas, each with a Geographic Area Coordination Center, or GACC.

GACCs:

- See everything inside their region

- Prioritize which incidents get scarce resources

- Move crews and aircraft between incidents and states

- Coordinate with state agencies, tribal partners, and federal units

Between local dispatch and the GACCs, tens of thousands of fires (50-70k estimated) are coordinated every year.

From a pattern point of view, a GACC is where portfolio thinking shows up in fire operations:

- You cannot send the only available Type 1 crew to every fire

- You cannot assign the same aircraft to three complexes at once

- You must weigh risk, values at risk, and forecasted fire behavior

The GACC has to answer questions like:

- Which fire gets the heavy air tanker

- Which incident has to make do with smaller aircraft or none at all

- When do we pull resources off a contained fire and send them to a new start

It is not purely top down. Local dispatch and incident commanders still own their piece. But once resources are scarce, the GACC becomes the broker of reality.

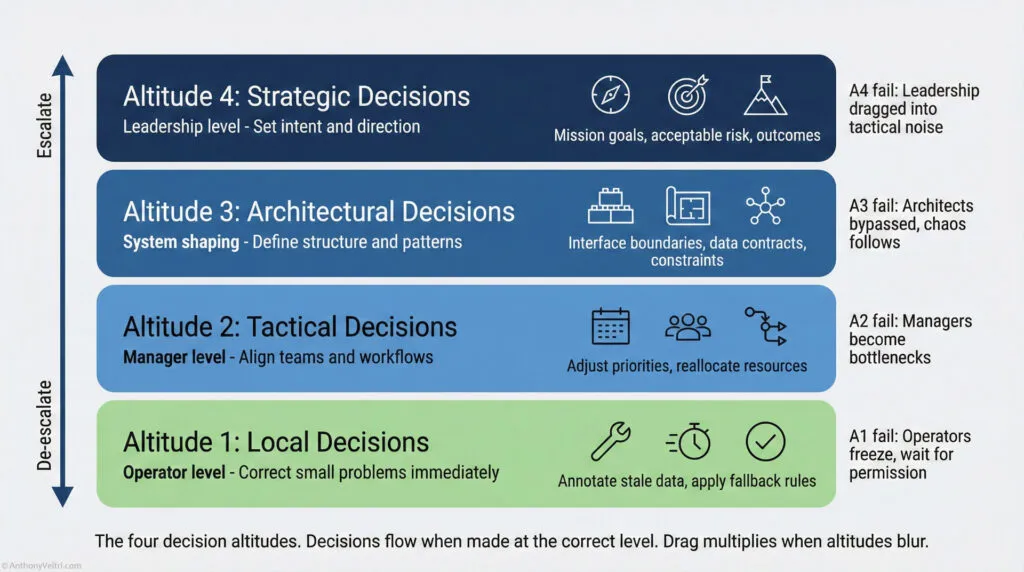

In my language, this is decision altitudes in action.

- Local: “Can we hold this flank by dark”

- GACC: “Which fires get scarce aircraft over the next 72 hours”

Both are valid. They just happen at different altitudes.

NICC And NIFC, The National Picture

Above the GACCs sits the National Interagency Coordination Center, or NICC, located at the National Interagency Fire Center in Boise.

NICC is the national focal point for:

- Coordinating the mobilization of resources for wildland fire and other incidents

- Monitoring fire activity across the country

- Setting national priorities when demand exceeds supply

The national system is explicitly three-tier:

- Local dispatch centers

- Geographic Area Coordination Centers

- NICC at NIFC

That three-tier model is what allows resources to move from the East Coast to the West Coast, or from Alaska to Florida, when the situation demands it.

At NICC, specialists:

- Watch multiple geographic areas at once

- Track national preparedness levels

- Work with the National Multi Agency Coordinating Group (NMAC) on high level prioritization

If you are used to data centers and control rooms, the feel is familiar.

Screens. Maps. Phones. Headsets. Decision boards.

The difference is that the “objects” being moved are not packets or virtual machines. They are:

- People and aircraft

- Crews and equipment

- Each with fatigue, maintenance, and risk profiles

This is the tier where my doctrine about portfolio thinking and decision drag comes into play.

- If NICC hesitates too long on a national move, multiple fires suffer

- If they move too fast without good information, they strand resources in the wrong region

The system is designed to reduce that drag, not by pretending uncertainty is gone, but by giving decision makers clear roles, doctrine, and playbooks.

Fire Aviation And The Airspace Stack

Inside this three tier dispatch system sits another layer that is particularly close to the world of airspace control and deconfliction.

Fire aviation.

When you have multiple aircraft, multiple incidents, and shared airspace, things can go bad very quickly if coordination is sloppy.

The National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG) publishes the Standards for Airspace Coordination, PMS 520. It standardizes safe, consistent approaches to airspace issues in the context of fire and land management responsibilities, and it helps people navigate the complexities of the National Airspace System around incidents.

In practice, that means:

- Temporary Flight Restrictions around incidents

- Fire Traffic Area procedures

- Defined roles like Air Tactical Group Supervisor and Airspace Coordinator

- Required training and task books for those roles

When you talk to someone like Mary, you feel the importance of this system in your bones.

She is not just “flying a King Air.” She is:

- A node in a doctrine driven airspace system

- A human sensor and decision maker at the edge of that system

- A translator between ground intent and aircraft capabilities

“Everybody that is involved in aviation is in support of something else.

When somebody on the ground lets us know that we helped them out, that is the rewarding part.”

It is not about the aircraft for its own sake. It is about the effect for crews on the ground and communities downstream of the fire.

Pipelines, Commitment, And The Human Side Of All This

One thing Mary highlights that does not always show up in technical diagrams is how people actually get into these roles.

“Right now, aviation is a really dynamic profession.

There is a huge demand for pilots in all facets of the industry, especially in the firefighting world.”

She talks about the real barriers:

- The expense of training

- The need to move for opportunities

- The importance of taking jobs that are not the dream, but still move you closer

Her advice to young people is simple and practical:

- Get close to the aircraft. Get a job at an airport, any job.

- Take an introductory flight. Those first two or three flights will tell you if you actually love it.

- Use scholarships and loans wisely. There are more of them than people realize.

- Be willing to change your dream. Your first goal may not be your final destination.

There is a direct parallel here to the way the system treats qualifications.

Task books, check rides, recurring training.

The system does not run on raw enthusiasm. It runs on people who have put in the time, passed the gates, and proven they can be trusted when things are genuinely bad.

Doctrine Parallels: What This System Taught Me

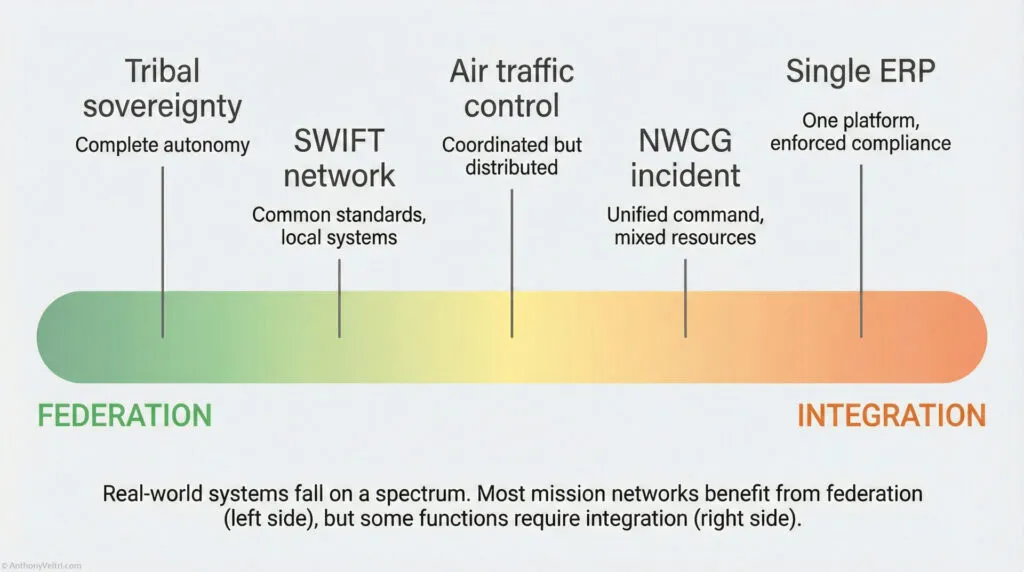

The fire system sits in the middle of the spectrum: “Coordinated but Distributed,” just like Air Traffic Control. It balances local sovereignty with national power.

The Lesson: Successful systems are often integrated locally (for control) but federated globally (for scale).

Working in and around this system shaped several of my core principles.

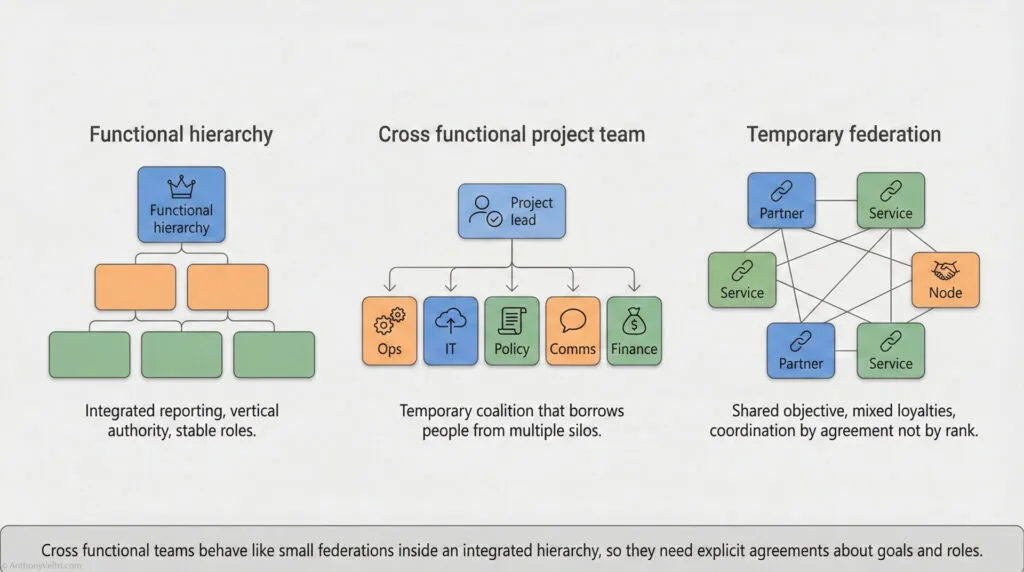

1. Federation, Not Forced Centralization

- Local dispatch, GACC, and NICC are distinct sovereign nodes

- Each has its own responsibilities and authority

- The system works because they are wired together by clear contracts, not because someone tried to erase their boundaries

That is why I talk so much about federation vs integration.

You do not need a single monolithic control center to get a coherent picture. You need well defined interfaces between nodes that respect each other’s sovereignty.

2. Clear Roles And Task Books

- NWCG position task books define what it means to be qualified

- Once you are signed off, you can plug into any incident in that role

- The system does not care whether you came from Forest Service, BLM, or Park Service once you are wearing the vest

That is task books turn commitment into swappable competence.

It is a human version of strong interface contracts. You are not just “Dave who is pretty good on radios.” You are a recognized role with known capabilities and responsibilities.

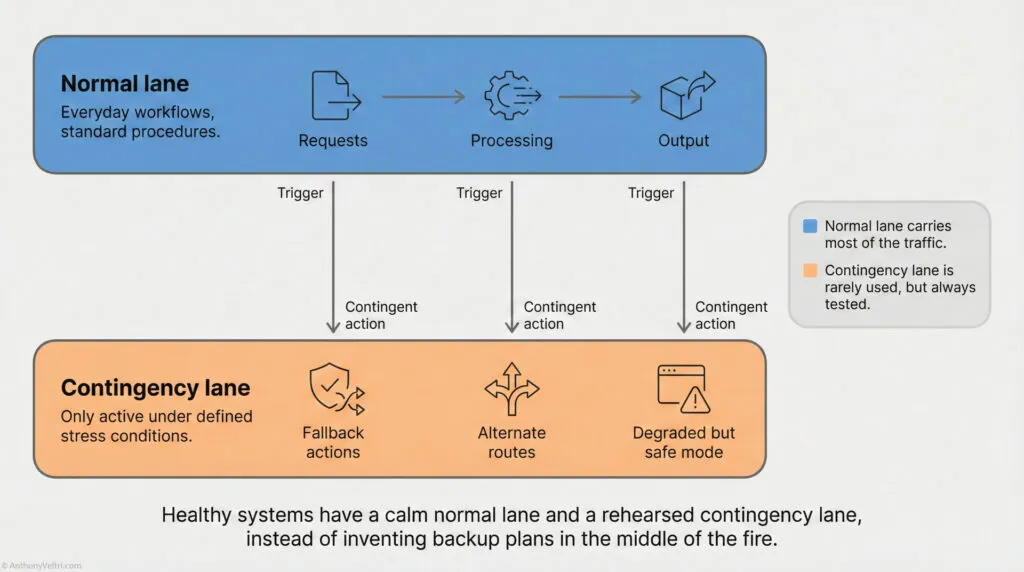

3. Degraded Operations As The Normal Mode

Fires start with incomplete information:

- Aircraft go unavailable

- Radios fail

- Roads wash out

- Plumes do things that models did not predict

NICC and the GACCs still have to make national level decisions.

You do not get to wait for a perfect national picture. You design and rehearse degraded modes on purpose.

That is why I care so much about concepts like:

- Last known good

- Fallback first

- Minimum viable publication

Fire and aviation taught me that if your system only works in ideal conditions, it does not really work.

4. Decision Altitudes And Portfolio Thinking

- Local dispatch focuses on immediate life safety and containment

- GACCs focus on regional priorities and resource sharing

- NICC and NMAC focus on national portfolio risk

When those levels blur, bad things happen. When they are clear, the whole machine can move with surprising grace.

The same is true in any complex mission system. If everyone is arguing at the wrong altitude, you get delay, confusion, and risk without anyone being able to say why.

Why I Care Enough To Write This Down

At the end of her interview, Mary talked about what surprised her most over two decades with the agency.

“Overall, over the decades, the biggest surprise that has been really cool in working for the agency is the sense of family.”

“I think that the impact we have on future generations is the protection and the preserving of the natural resources.”

That line matters.

This system is not just about fire numbers, flight hours, or airtanker sorties. It is about:

- Protecting communities

- Protecting firefighters

- Protecting the landscapes that our kids will inherit

For me, this guide is not nostalgia.

It is about recognizing that some of the best thinking on large-scale coordination is quietly embodied in places like:

- NIFC

- GACCs

- Local dispatch centers

- Airbases and tanker pits

- Lead planes flying smoke filled valleys

Not just in white papers and strategy decks.

If you work in national security, critical infrastructure, or any high-tempo environment, there is a lot to learn from how fire and aviation manage:

- Scarce resources

- Incomplete pictures

- Multiple sovereign organisations

- High risk operating environments

This three tier dispatch system, and the aviation layer that rides on top of it, is one of the clearest real world examples of a federated, doctrine driven, high tempo network that I have ever seen.

It is where a lot of my doctrine comes from.

And it is why I take wildland fire so seriously when I talk about architecture, leadership, and mission systems in other domains.

Last Updated on January 19, 2026