Human Contracts Under The Air Picture

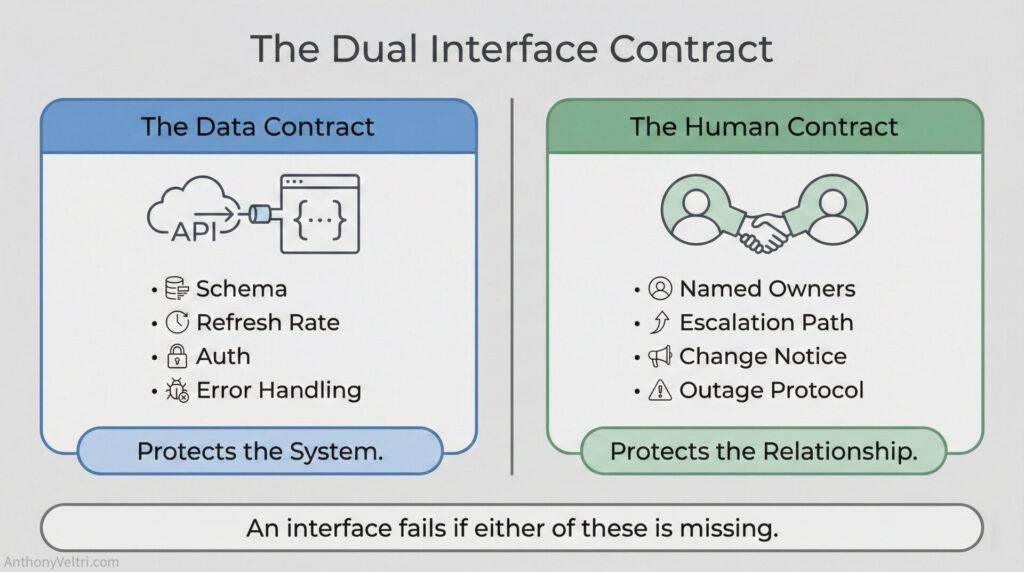

Every complex system has code, data and diagrams.

Underneath all of that, it has human contracts.

Not the legal documents, although those matter too.

I mean:

- Who trusts whom

- Who listens to whom under stress

- Whose word carries weight in a briefing

When human contracts are clear, systems can be messy and still work.

When human contracts are broken or absent, even perfect architectures will fail under load.

Pastor vs Relief Organization

The Bay St Louis church after Katrina is a simple example.

The relief organization arrived with:

- Trucks

- Supplies

- Procedures

The pastor and community already had:

- Local knowledge

- Informal supply chains

- A working social graph

There was no human contract.

The relief organization assumed:

- “We arrive, we are in charge of all the supplies”

The pastor’s response was blunt:

“We appreciate and need your supplies. What we do not need is your management of a reality you only understand on paper.”

Without a human contract that respected local sovereignty, the interface between systems became a power struggle.

No amount of logistics software would have fixed that.

Wildland Fire: The Positive Case

In wildland fire, the human contracts come first.

Before the big incidents, agencies have:

- Shared doctrine under NWCG

- ICS roles everyone respects

- Task books that turn commitment into observable performance

By the time crews and overhead arrive at a large fire, they already know:

- Who an IC is

- What a division supervisor does

- How decisions get made at briefings

They may come from different badges, but the human contract is clear:

- “On this incident, we follow this playbook”

- “These roles carry this authority”

- “We back each other inside this structure”

That allows multiple systems, agencies and vendors to work together with far less friction than you would expect from the outside.

Platforms And Systems Are Not Enough

In any mission network, including air systems, you can connect platforms technically and still fail operationally.

Platforms and systems can:

- Exchange data

- Render pictures

- Enable commands

They cannot decide:

- Which partner speaks first

- How a conflict between caveats is resolved

- Who has the moral authority to say “stop”

That is human work.

If you do not do it early, you end up trying to negotiate it in the staging area. Under stress. In public.

Designing Human Contracts On Purpose

When I think about human contracts under technical systems, I ask:

- Who are the real local authorities, not just the org chart names

- What have we agreed they control, explicitly

- What promises have we made each other about how we will behave in a crisis

- How will we handle disagreement when the clock is ticking

In coalition environments, that might be:

- Between nations

- Between different operational commands

- Between intelligence providers and operational users

The doctrine is simple:

“Write the human contract before you stress the technical system.”

If you do that, your platforms, feeds and tools have a chance to shine.

If you do not, you will end up with beautiful code on top of brittle relationships.

Last Updated on December 7, 2025