Interfaces Break First: Designing For Partial Truth

Every messy mission system has one reliable pattern:

The interfaces break first.

They break:

- Technically, when schemas drift or feeds choke

- Politically, when caveats collide

- Socially, when trust is not there yet

You see it clearly any time you try to connect worlds that were never designed for each other.

When Systems Touch Without Consent

At DHS I saw this in several places:

- National systems consuming data from tribal nations and local governments

- Disaster response trying to treat church parking lots as formal staging nodes

- The Federal Register touching internal drafting, legal review and public expectations

In each case, someone tried to treat the boundary as if it were just another internal function.

It never was.

A tribal data steward does not work for DHS.

A pastor in Bay St Louis does not report to a relief NGO.

External reviewers of a Federal Register notice do not answer to the drafting team.

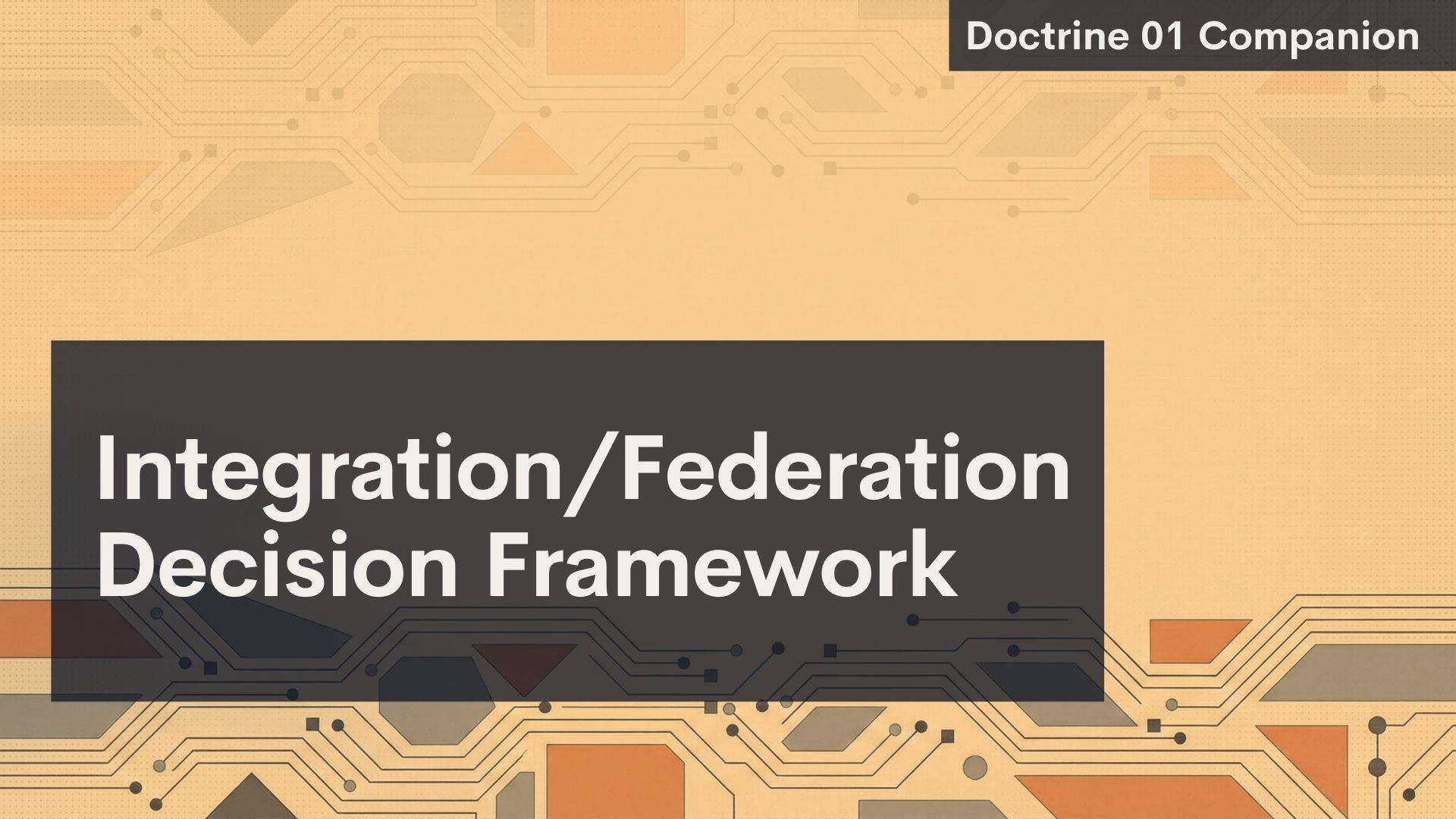

From an interface perspective, those are federated nodes, not internal components.

If you design the interface as if you own both sides, you will break it.

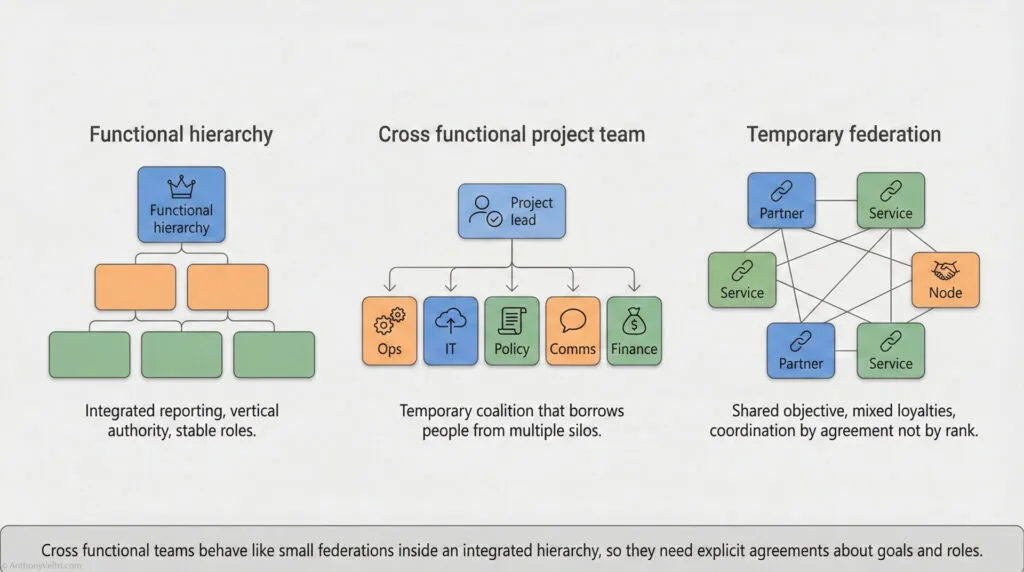

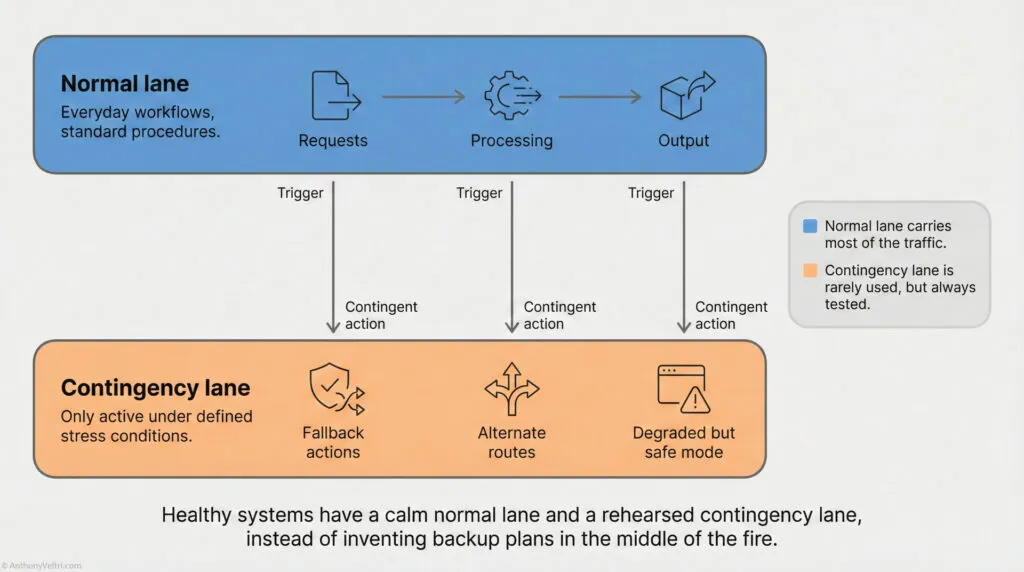

Partial Truth Is The Norm

Architectural Slack: Designing for the “Legal Limit” creates a Single Lane system. Respecting the envelope means building a “Contingency Lane” (Orange) so you have space to maneuver when the weather turns. Shifting Lanes: When the circumstances turns against you, you leave the “Normal Lane” (Efficiency) and enter the “Contingency Lane” (Survival). You cannot fly a “Blue Lane” mission in “Orange Lane” conditions. The Reality of Operations: In high-tempo systems, the “Normal Lane” (Perfect Data) is often blocked. You must design the “Contingency Lane” (Partial Truth) to keep the mission moving.

In iCAV, we rarely had full truth at a boundary.

- Some partners could give precise, fresh data

- Others could only give periodic snapshots

- Some fields were redacted for policy reasons

What we had was partial truth with caveats.

Trying to pretend that every feed was equal would have been dishonest. The right move was to:

- Accept that some truth is better than none

- Make the caveats visible

- Design clients to handle missing or older data gracefully

An interface that insists on complete, uniform truth will spend most of its life failing.

Classification, Caveats And “Need To Share”

In any serious mission network you also have classification and caveats.

- Some partners can see raw tracks

- Some can only see a filtered or delayed view

- Some cannot see certain sources at all

If you design the interface as “everyone sees everything,” you are designing for a world that does not exist.

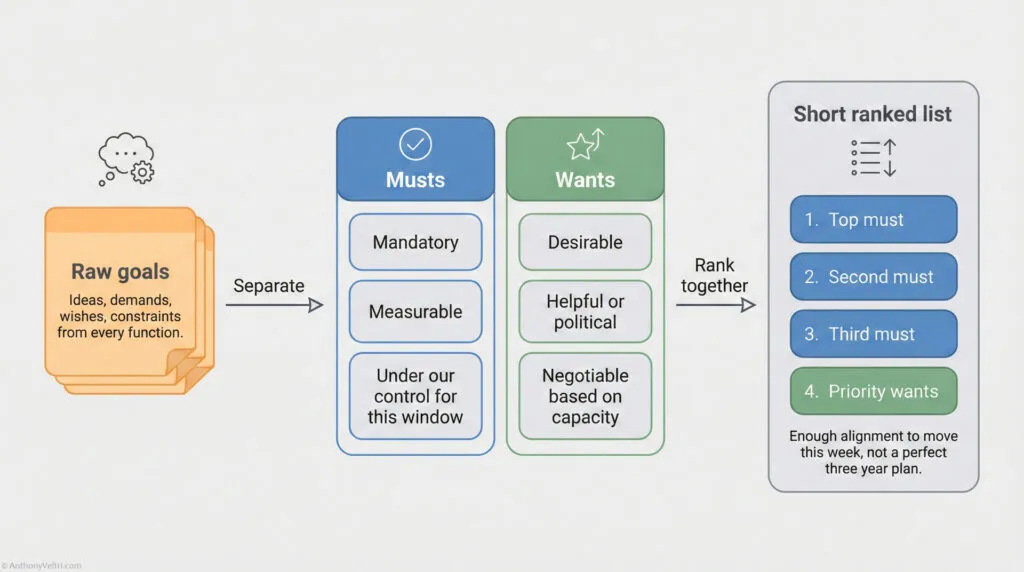

The real design problem is:

“How do we provide honest, useful partial truth at each boundary”

That requires:

- Understanding what each side can really share

- Making that explicit in data contracts

- Accepting asymmetry as normal, not as a bug

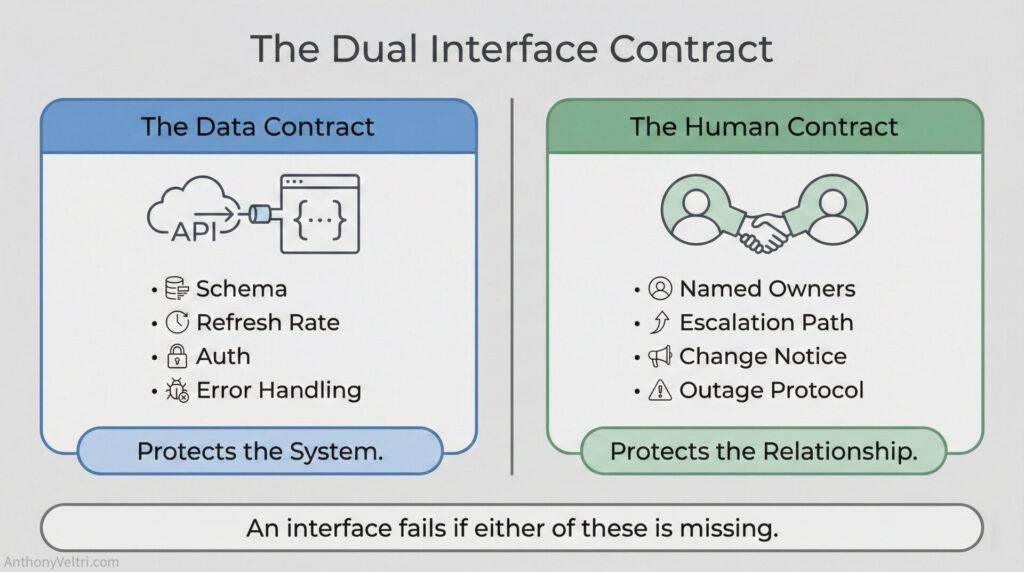

Human Contracts Before Data Contracts

Technical interfaces ride on human contracts.

The Bay St Louis pastor refusing to be managed by a relief org is a human contract failure.

There was:

- No pre-agreed understanding of who owned what

- No recognition of sovereignty

- No shared playbook for resource management

In wildland fire, the opposite is true. Agencies talk and exercise before the incident. They have human contracts about how they will behave when systems touch.

The same logic applies at technical boundaries.

You need:

- Named points of contact on each side

- Clear escalation paths

- Shared understanding of what “good enough” looks like

Only then do your JSON schemas and cross domain guards have a chance.

Design Rules I Use At Boundaries

When I design or critique interfaces, I use a simple checklist:

- Who owns each side of this boundary, by name

- What are they allowed to share, in reality, not on the org chart

- How stale is acceptable for each field

- How do we represent “I know something here but cannot share it”

- What is the fallback when this feed dies

If those questions cannot be answered, the interface is not ready for a crisis. It might be ready for a demo.

The doctrine lesson:

“Interfaces are not pipes between databases. They are negotiated truths between sovereign actors.”

Treat them that way and you will break fewer things when it matters.

Last Updated on December 7, 2025