Pattern-Matching as Operational Knowledge: Why Expertise Requires Documentation

Or: What Rock Climbing Taught Me About How All My Work Actually Functions

The Realization

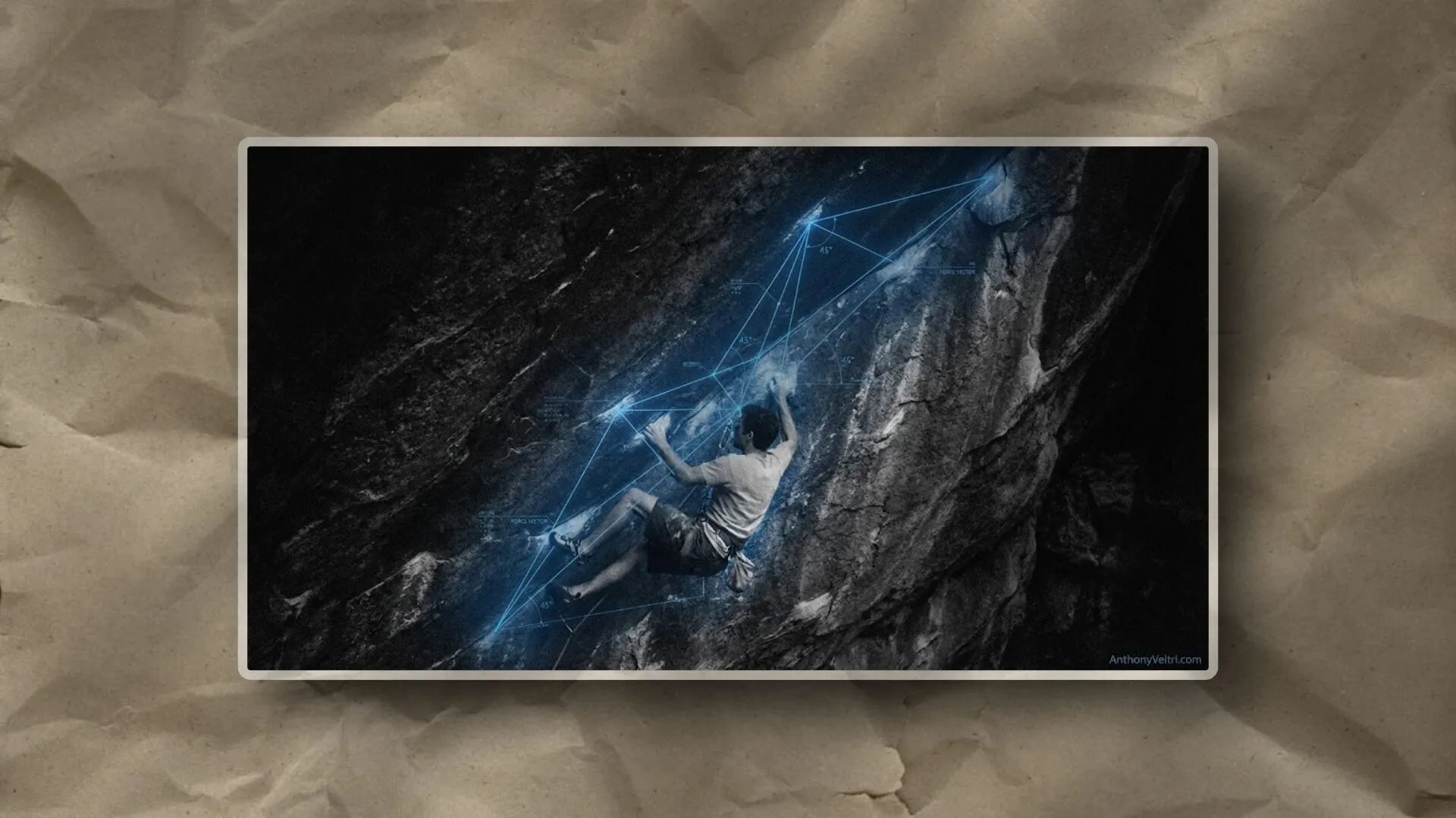

I was writing about bouldering recently. How practicing hard moves close to the ground lets you build muscle memory and recognition so that when you encounter similar patterns 40 feet up, your body knows what to do without conscious analysis.

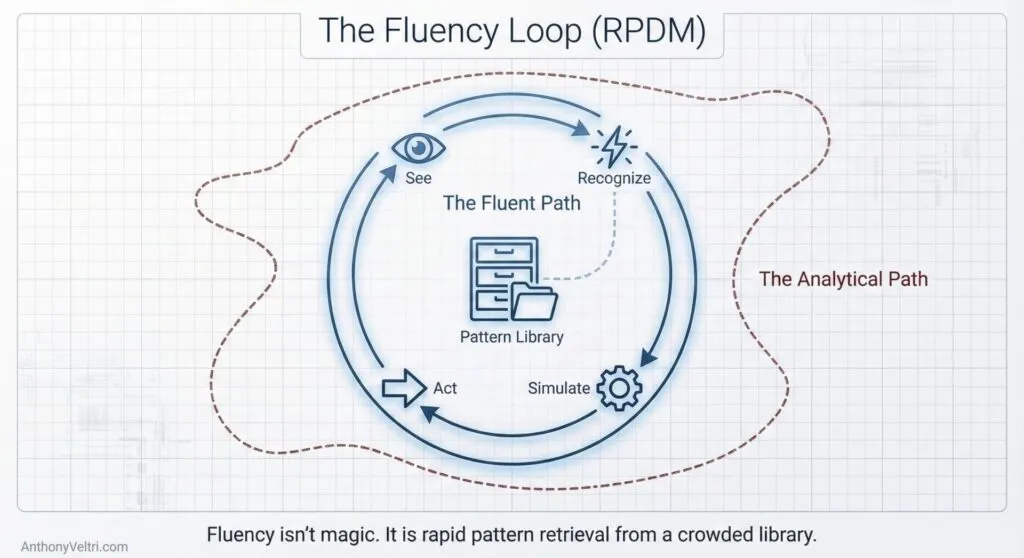

Then I realized: that’s not just bouldering. That’s pattern-matching. That’s recognition-primed decision making (RPDM).

Then I realized it again: jiu-jitsu works the same way. You drill positions and transitions hundreds of times so that during live rolling, when someone starts a sweep, your body recognizes the pattern and responds before your conscious mind catches up.

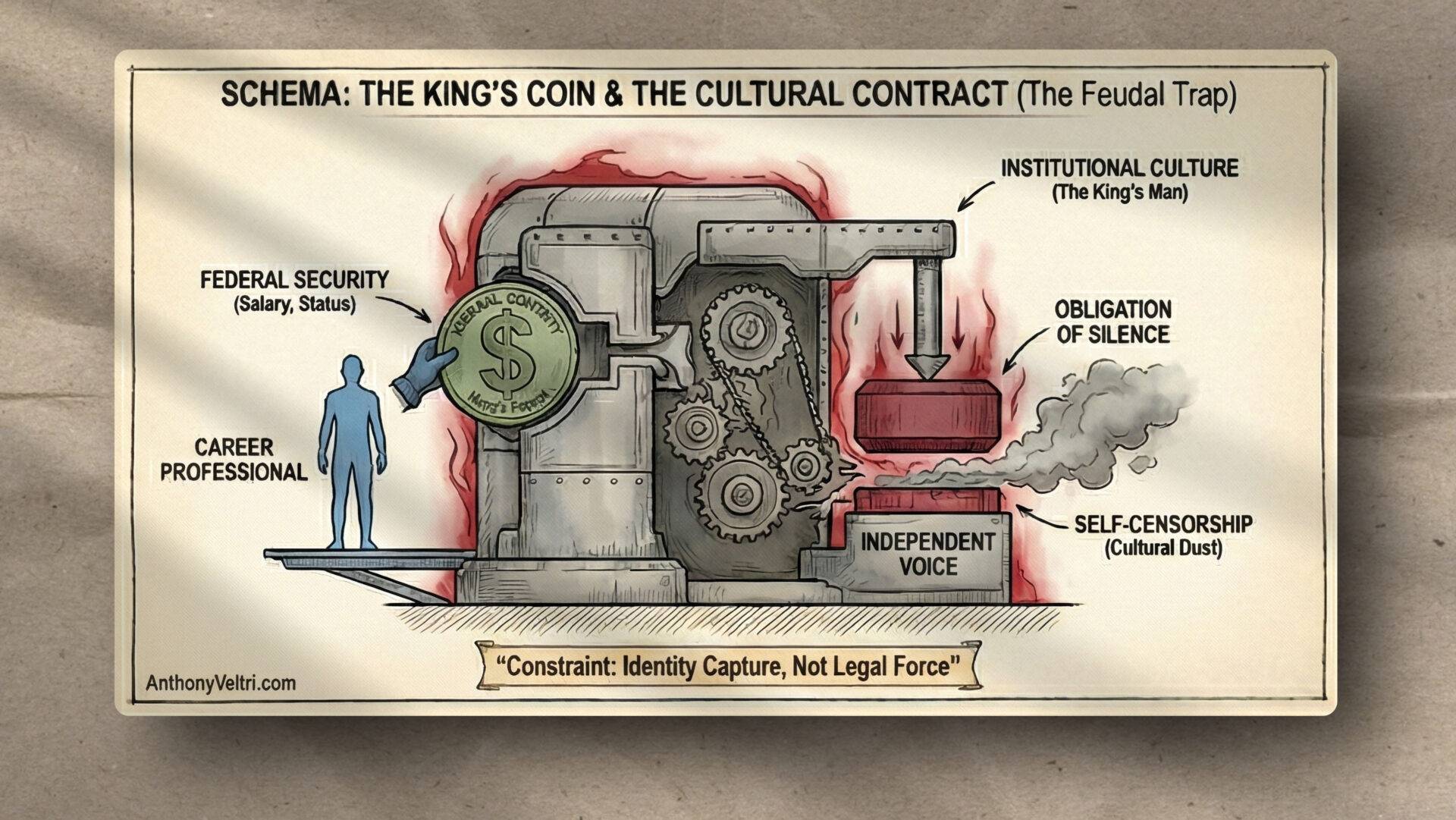

But Jiu-Jitsu taught me something else about patterns: sometimes your environment makes you blind to your own parameters.

I Didn’t Know I Was Short

I literally did not know I was in the lower quintile for height until I started Jiu-Jitsu in my late 40s.

For 45 years, I had no idea.

I was a climber. In climbing, the environment makes height irrelevant. It’s a trade-off: being tall gives you reach, but being short lets you fit into crunched positions that spit taller climbers off the wall. Moreover, it is something that even beginners can take advantage of. Because the environment offered solutions for every body type, my height was invisible to me. I wasn’t “masking” it. It just wasn’t a variable that mattered.

But Jiu-Jitsu is different. Especially when you are a white belt (and especially when you are ME as a white belt).

Yes, a skilled small person can dominate a large but unskilled (or low-skilled) person. Skill eventually overrides attributes. But when you’re a white belt, before you have patterns to recognize and counter, physics is the only law that matters. When you are trying to retain guard or lock up a triangle choke against a resisting opponent, you can’t “technique” your way out of the fact that your legs are shorter than their torso.

The environment stripped away the blindness. It forced me to acknowledge a parameter (my height) that climbing had allowed me to ignore for decades.

The Bigger Pattern

This is the bigger realization: everything I do works this way.

The session hijacking bug I stumbled upon in 1999 taught me patterns about client-side trust that shaped how I approached zero trust architectures 15 years later. The mobile mapping unit deployments during disaster response taught me patterns about equipment staging. The SQL query I learned for photo distribution taught me relational thinking.

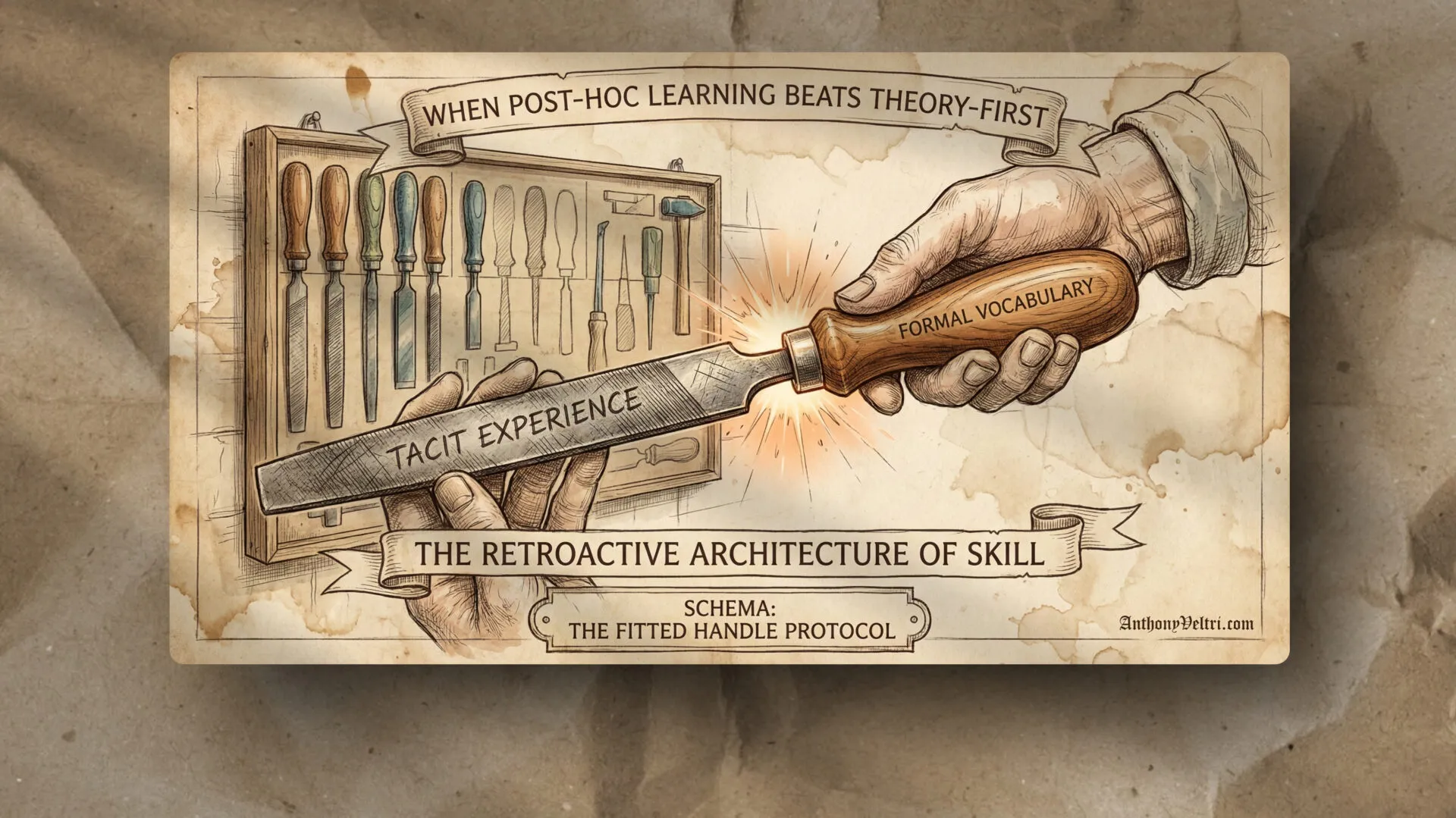

I’ve been operating through pattern recognition my entire career. I just didn’t have vocabulary for it until now.

And here’s the uncomfortable part: I assumed everyone works this way.

And if I didn’t know I was short for 45 years, what other patterns have I built without realizing they’re patterns? What other adaptations feel routine to me but are actually specialized responses to constraints I don’t consciously recognize?

How Operational Fluency Actually Works

Gary Klein spent decades studying how people make decisions under pressure. Firefighters, ICU nurses, military commanders. He used the term “expert” to describe them, but I’ve always been uncomfortable with that word.

Why I Prefer “Fluency” Over “Expert”

To me, “expert” feels like a title. It implies a crown, a credential, or a summit you’ve reached. In my experience (whether on the mats in Jiu-Jitsu or in federal server rooms), thinking you’ve reached the summit is usually the fastest way to get humiliated.

I prefer the word fluency.

When you are fluent in a language, you don’t diagram the sentence structure in your head before you speak. You don’t look up the conjugation tables. You just speak. You hear a wrong note and you correct it instinctively.

Klein’s research (specifically his work on Recognition-Primed Decision Making) provides the mechanical definition for this fluency. He argues that what we call “expertise” isn’t about raw intelligence or accumulating credentials. It’s simply about the size of your pattern library.

The Recognition Mechanism

Here’s the mechanism:

Encounter: You see a situation (a server lag, a specific grip in Jiu-Jitsu).

Match: You match it to a file in your library (“I’ve seen/heard/felt this before”).

Simulate: You run a quick mental check (“If I do X, Y happens”).

Execute: You act.

There is no “expert” crown here. Who credentials pattern recall? Nobody. There is no university degree for “having seen a lot of weird PHP bugs.” You don’t get a certificate for recognizing a specific hip movement in grappling.

You just get fluent.

The difference between a novice and a proficient operator isn’t that the operator is smarter. It’s that the operator has a crowded file cabinet, and the novice has an empty one.

My Crowded File Cabinet

I am not claiming to be a guru. I am simply claiming that after 25 years of shipping crash pads, debugging code, and deploying federal systems, I have a very crowded file cabinet.

But the real trick isn’t the storage. It’s the retrieval.

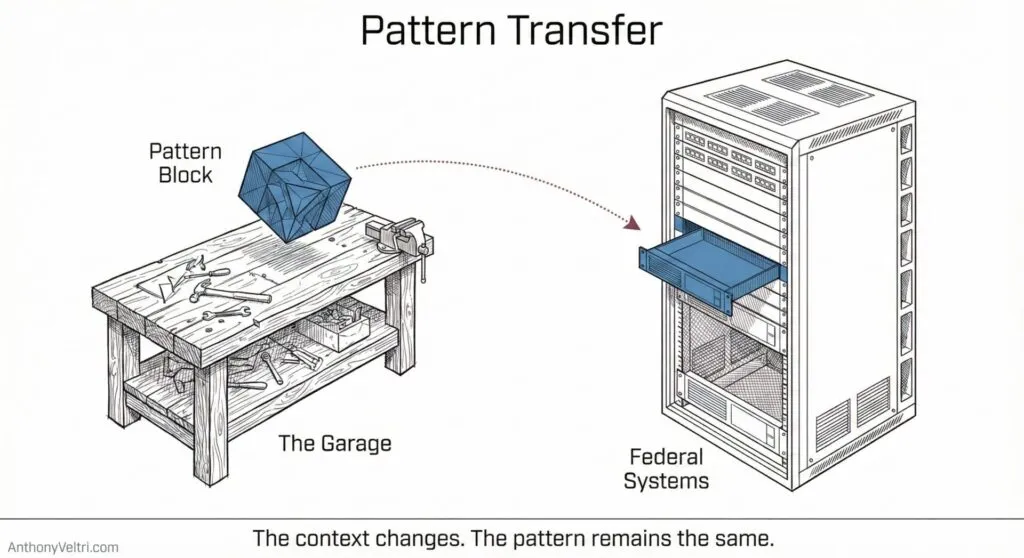

Most people file their experiences by category: Climbing goes in the sports folder. Coding goes in the work folder. I’ve realized my system is indexed differently. I cross-reference everything by mechanism.

The “Session Hijacking” file isn’t stored under Technology. It’s stored under Trust Boundaries, right next to the files for Disaster Response and Jiu-Jitsu Defense.

That cross-indexing is what looks like magic from the outside. It’s not magic. It’s just a retrieval system that ignores domain labels and looks for structural matches.

How Pattern Libraries Get Built

Pattern libraries come from repetition under varied conditions. You need enough reps to recognize “I’ve seen this before” and enough variation to know when the pattern applies versus when it doesn’t.

Physical Pattern Libraries

Bouldering rehearsal. Jiu-jitsu drilling.

You practice the same moves hundreds of times so your body recognizes the situation and responds without conscious analysis. When you encounter an undercling in a dihedral corner, you don’t think through hand positions. Your body knows the pattern.

Technical Pattern Libraries

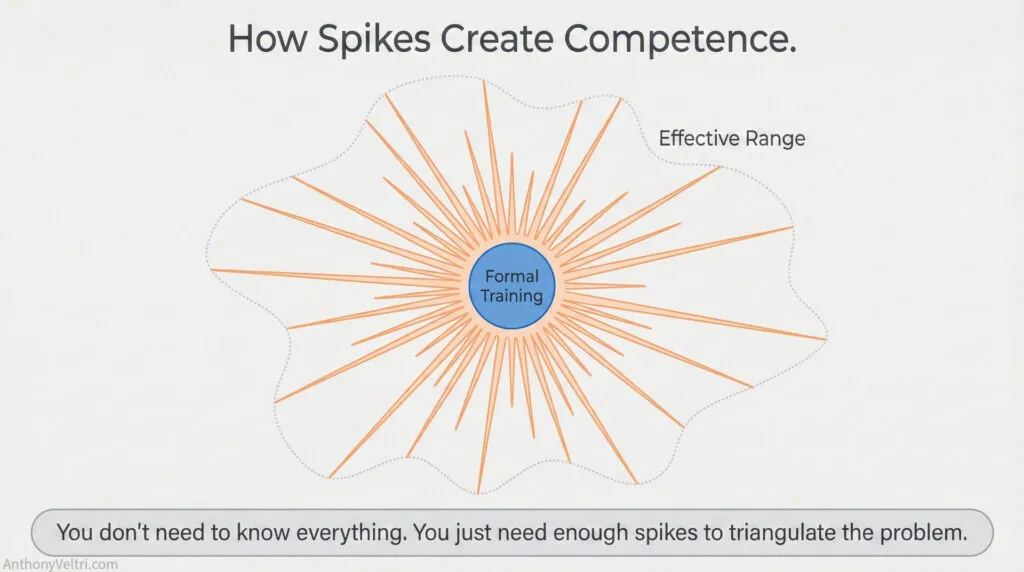

What I call Sphere and Spikes (broad general awareness with deep, specific spikes of proficiency).

You don’t become a deep specialist in everything. You acquire just enough patterns in a domain to recognize situations and respond effectively. I learned SQL inner joins because I needed them for a specific query. That pattern then applied to dozens of other problems. I didn’t need to become a database administrator. I needed enough reps to recognize “this is a relational data problem” and know which pattern applies.

Systems Pattern Libraries

The doctrine system and ANNEX F are explicit pattern libraries. “This is a federation problem.” “This is an interface ownership problem.” “This is a trust boundary problem.”

Recognizing the pattern lets you apply pre-validated solutions instead of treating every problem as unique.

The pattern library in ANNEX F isn’t my patterns. It’s a pattern library. Reusable solutions to recurring problems that show up across mission systems, bureaucratic environments, and high-visibility workflows. Use what applies to your context. Ignore what doesn’t.

Why This Matters for Documentation

Here’s where this connects to stewardship.

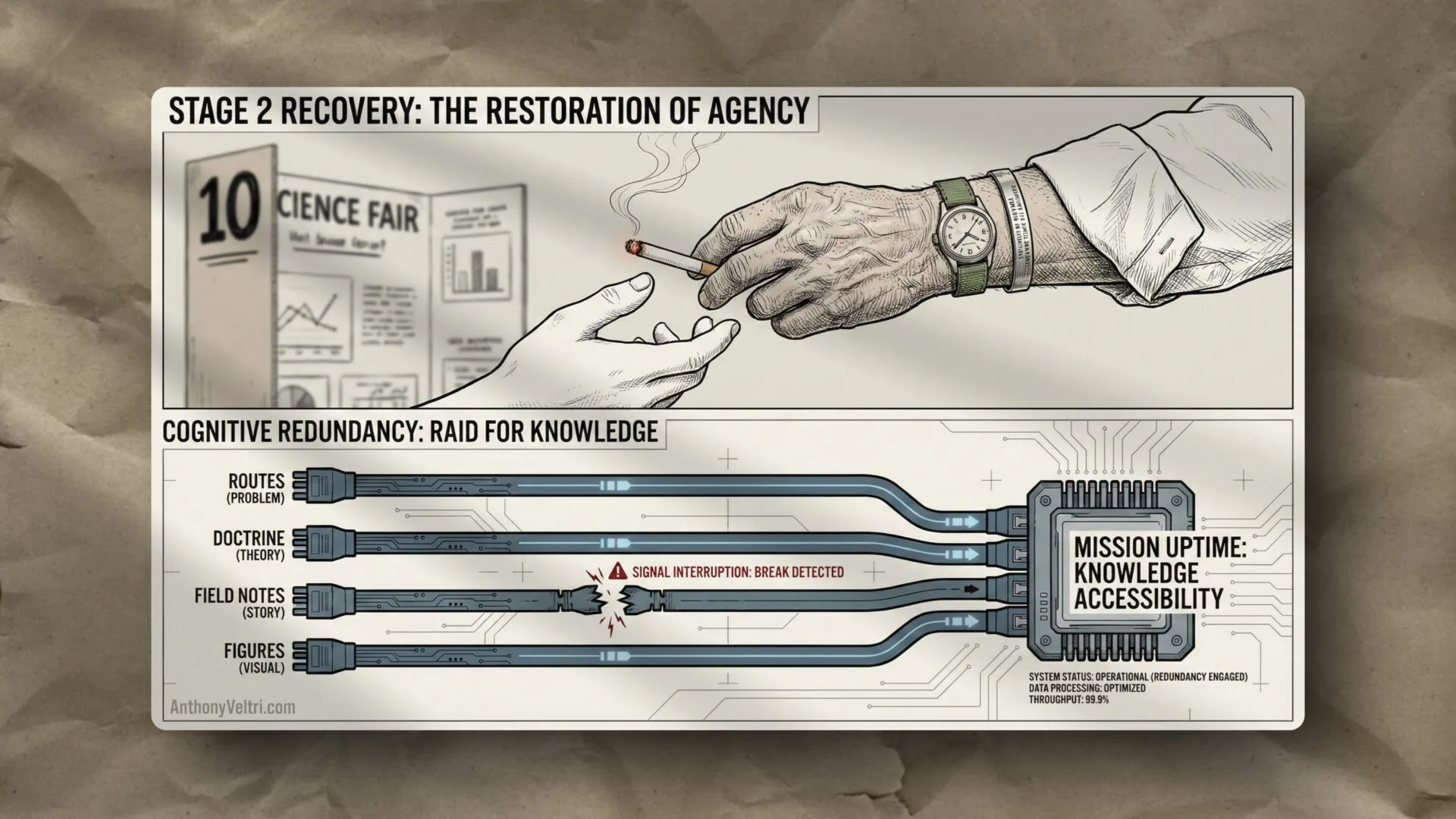

Klein’s research shows that operators build pattern libraries through sustained operational exposure. But here’s the problem: pattern libraries are tacit until someone documents them.

The Scythe Problem

When scythes were common tools, everyone who used them knew how to sharpen them. No one thought to write it down. Then scythes stopped being common, and that knowledge disappeared. Now people trying to revive scythe use struggle to figure out techniques that were once universal.

The Pyramid Problem

The same thing happened with pyramid construction. We can measure the pyramids. We can analyze the materials. But the tacit knowledge of how teams organized, how labor was coordinated, how tools were used? That’s gone. It was probably common knowledge to the people doing the work. Too obvious to document. Then it wasn’t common anymore, and we lost it.

The Universal Pattern

This is the pattern: when knowledge is tacit, it feels unnecessary to document until it’s too late.

Last Updated on December 22, 2025