Regime Recognition and the Cost of Asymmetric Errors: When Post-Hoc Learning Beats Theory-First

Scene: Dreaming in German

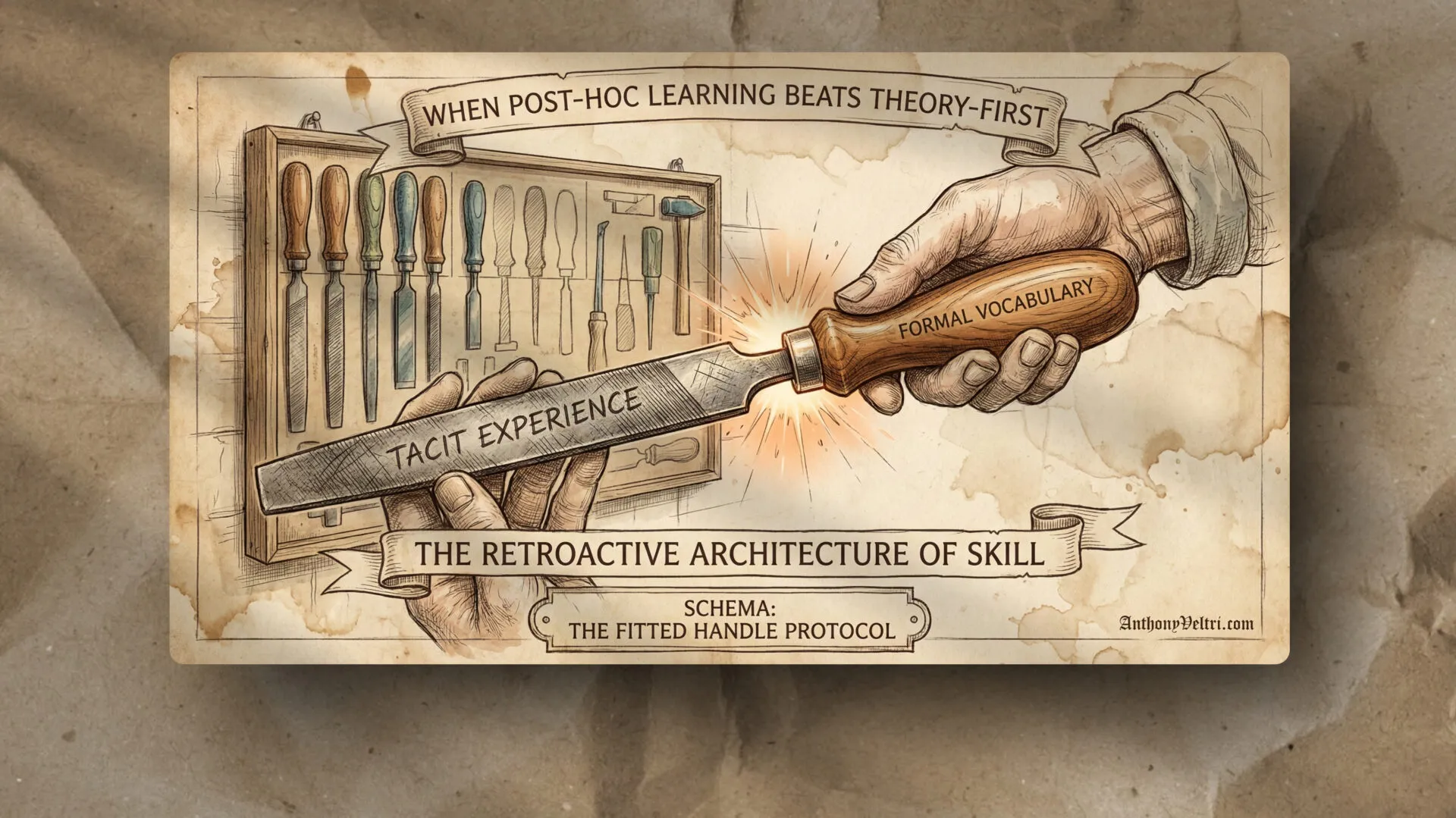

I’m describing a pattern: capability-first builds operational tools, and post-hoc theory (learning the formal framework after developing capability) provides handles that make those tools transferable.

I started dreaming in German. Not just thinking in German during conversations or while reading, but actual dreams where German was the native language of my subconscious. Not all the time, but enough to notice and remember the dream when I awoke. That’s when I realized something had fundamentally shifted.

I’d spent six years studying Spanish in high school and college. Theory-first. Verb conjugation tables. Grammar rules. Structured curriculum. I learned it “the right way.” Result: I could conjugate verbs and read some sentences, engage in basic A1-level conversation, but didn’t think in Spanish. Didn’t dream in Spanish. Decades of that “second language” sitting there, mostly unusable and unused.

But German, French, and Italian, which I’m learning now through immersion and use, work differently. I encounter the language, I try to use it, I make mistakes, I correct them. Then I learn the grammar terminology to describe what I’m already doing. When I learn “dative case,” I’m not learning a brand new concept. I’m learning the formal name for something I’m already doing (mostly) correctly in context.

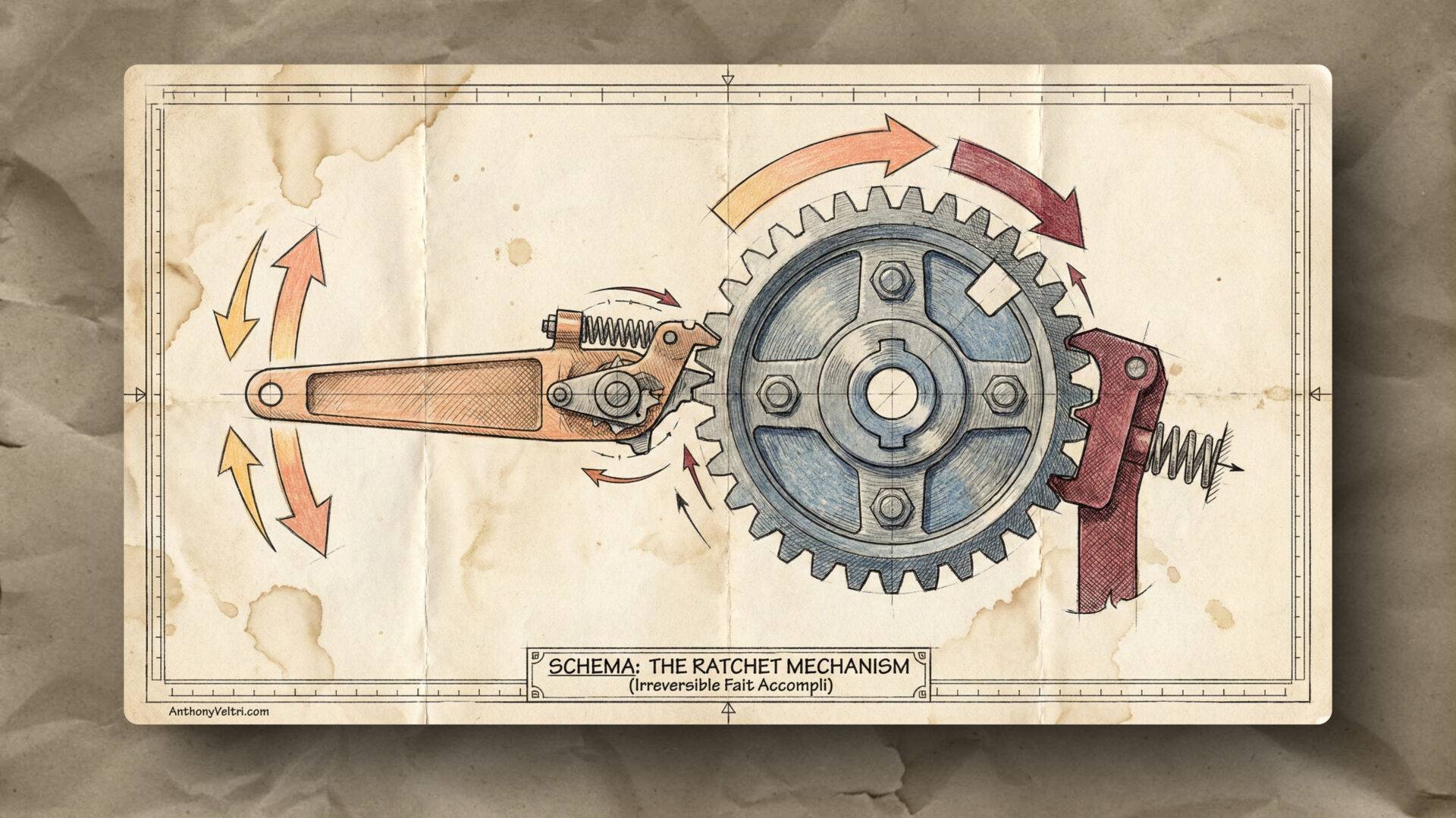

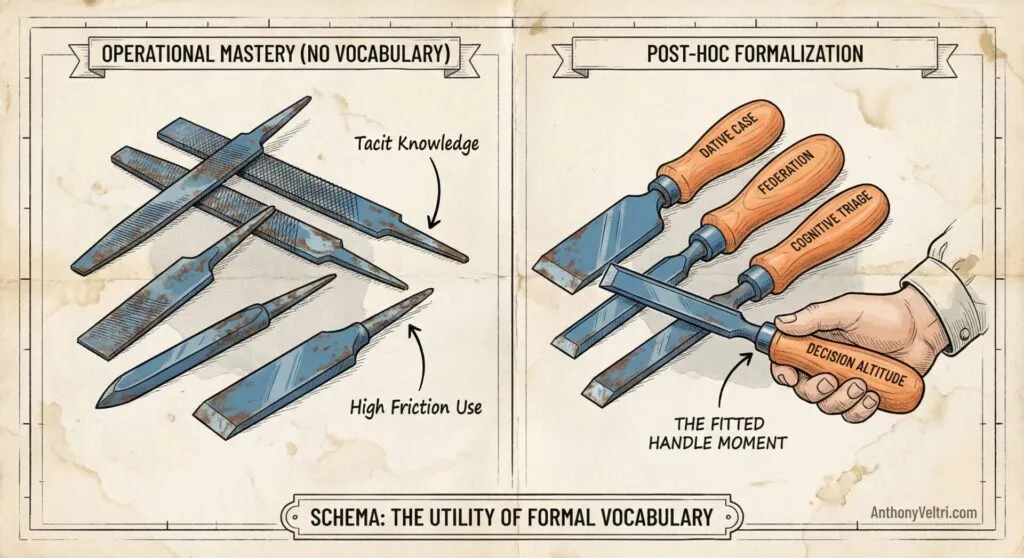

The German dreaming moment made me realize what post-hoc learning actually provides. It’s like having chisels and files that you’ve used for a lifetime and mastered, but without fitted handles. As you may know, a rat tail file can be fitted into a handle or not. You can use it either way. But with a handle, the tool becomes vastly more effective. Many hand tools are like this.

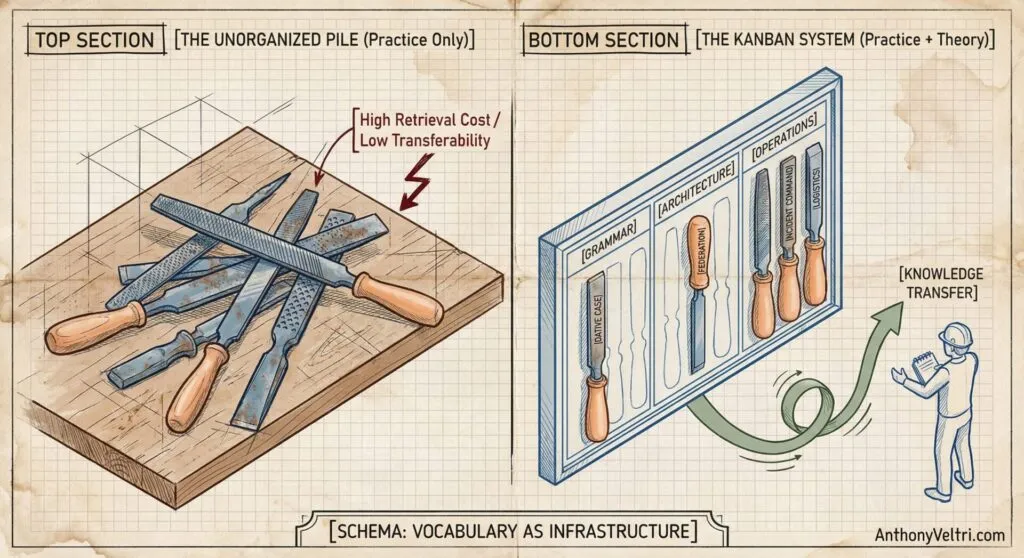

Post-hoc learning the definitions was like getting fitted handles for all these tools I’d been using handleless my entire operational life. But it wasn’t just handles. It was also a way to organize them, kanban style (like a shadow board for the mind). The formal vocabulary gave me structure. It let me see which tools served which purposes. It let me explain to someone else not just what I was doing, but why, and how they could do it too.

Two realizations hit me. First, the theory was actually fairly easy to learn once I had sufficient operational mastery. The German grammar made sense because I’d already internalized the patterns through use. Second, having the formal vocabulary made me incredibly more effective at explaining these concepts to other people. My wife. My children. Colleagues who were trying to understand federation problems or disaster response patterns.

That didn’t happen by accident, but I didn’t necessarily cause it on purpose either. It was just the realization that I could unlock the ability to communicate with a giant slice of people just by picking up new handles for the tools I’d already mastered. The watershed moment wasn’t learning new skills. It was learning the names for skills I already had, and discovering that the names were the transfer mechanism.

Break: The Handbook Doesn’t Always Describe Reality

The Spanish experience taught me what happens when you learn theory-first. You get the handles, but you don’t have the tools to attach them to. Six years of verb conjugations didn’t give me conversational fluency. It gave me terminology for capabilities I didn’t possess.

Theory-first assumes the framework will teach you the thing. Here are the rules, now apply them. But language doesn’t work that way when you’re actually using it. Native speakers violate formal rules constantly. Idioms don’t follow grammar logic. Context determines meaning. I was trying to apply constraint-based learning (here are the rules, follow them) to an exception-dominated domain (people use language in ways that routinely violate the formal rules).

The handles without tools problem shows up everywhere, not just in language learning. I’ve watched people complete formal project management training and then fail to manage actual projects because the methodology didn’t map to operational reality. I’ve seen people study disaster response theory and then freeze in actual emergencies because the handbook didn’t describe what was actually happening in front of them.

Theory-first works when the theory accurately maps to operational reality. When the rules describe what actually happens. When the constraints hold. But most interesting work happens in exception-dominated environments where the handbook is aspirational rather than descriptive.

Practice-first with post-hoc formalization works differently. You develop the tools through operational use. You learn what works through friction and feedback. Then you learn the formal vocabulary that lets you organize those tools, explain them to others, and see connections across domains.

This is what I realized when I started dreaming in German. I wasn’t just learning a language. I was learning the correct sequence: develop capability first, then learn the formal framework that describes and organizes that capability.

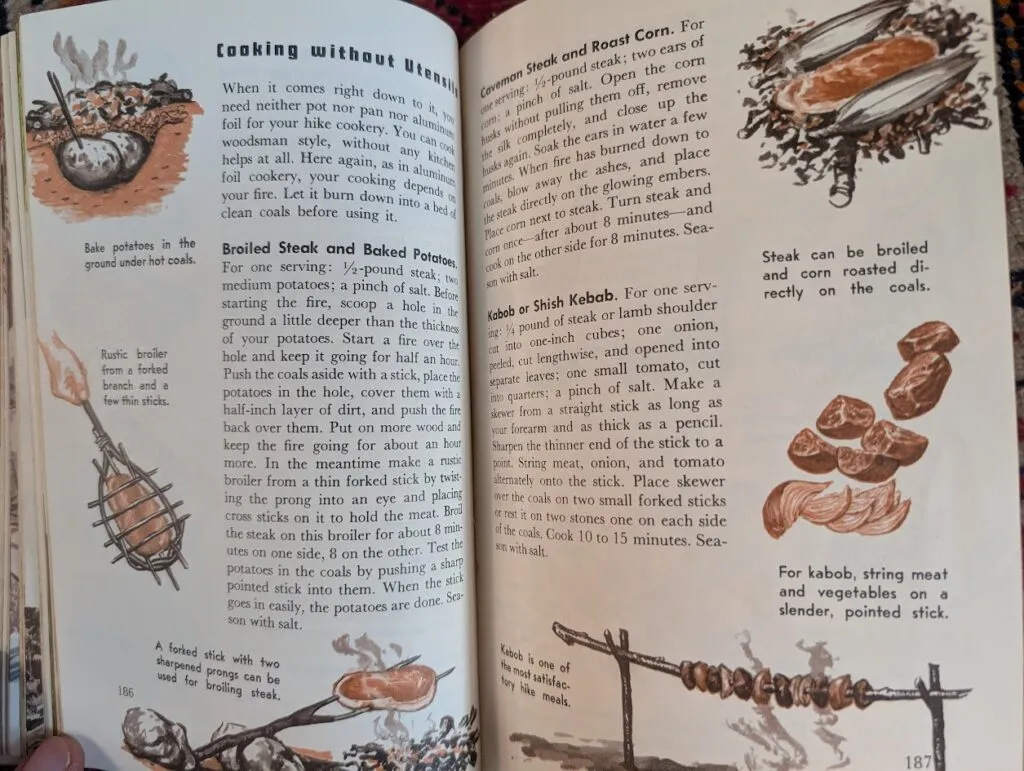

The Boy Scout Handbook and Regime Recognition

I grew up believing the rules described reality. I memorized the Norman Rockwell illustrated 1959 Boy Scout Handbook as a child. I wanted to follow the handbook, follow the regulations, learn the whole system. I thought if we just followed the manual, everything would work.

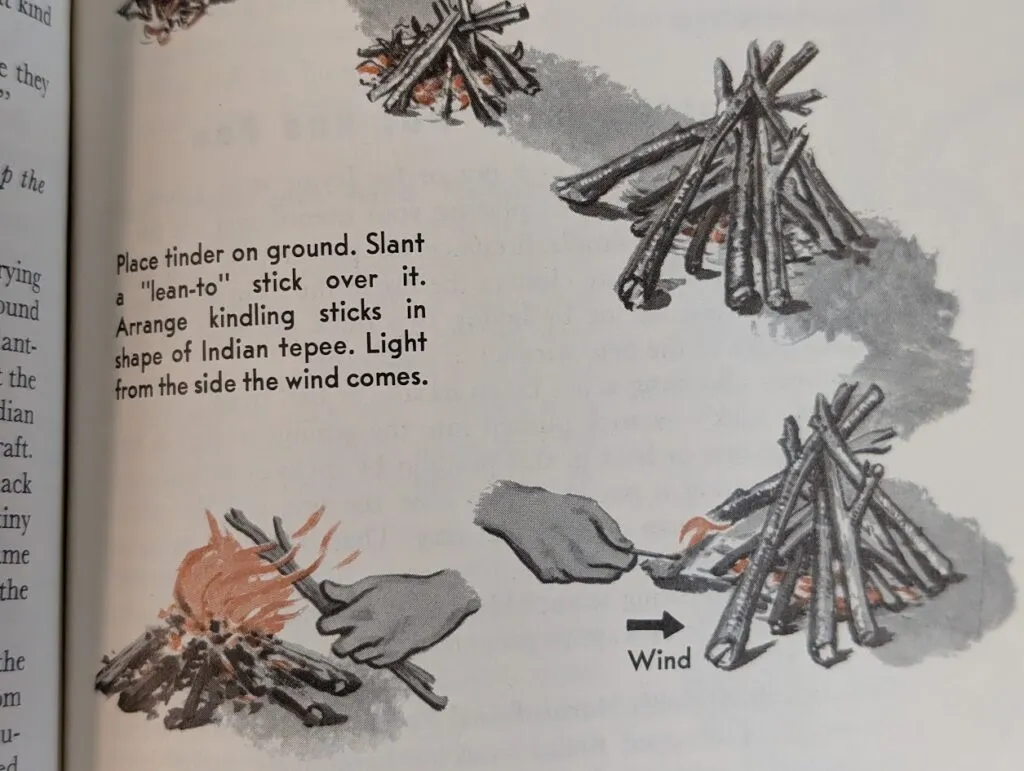

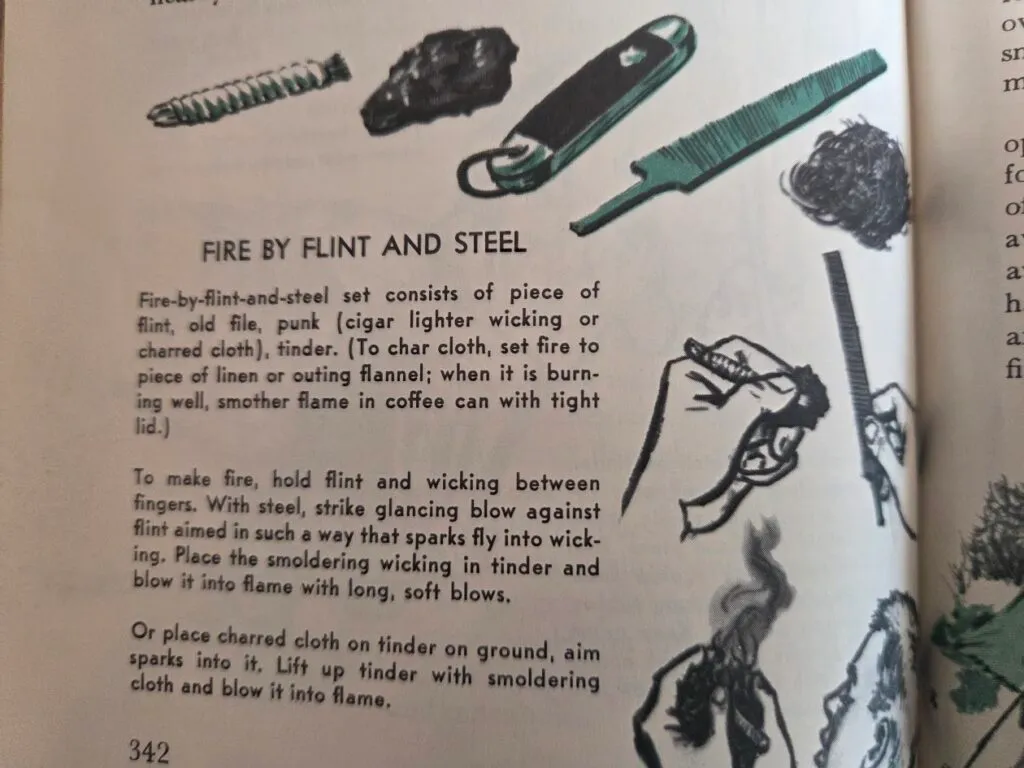

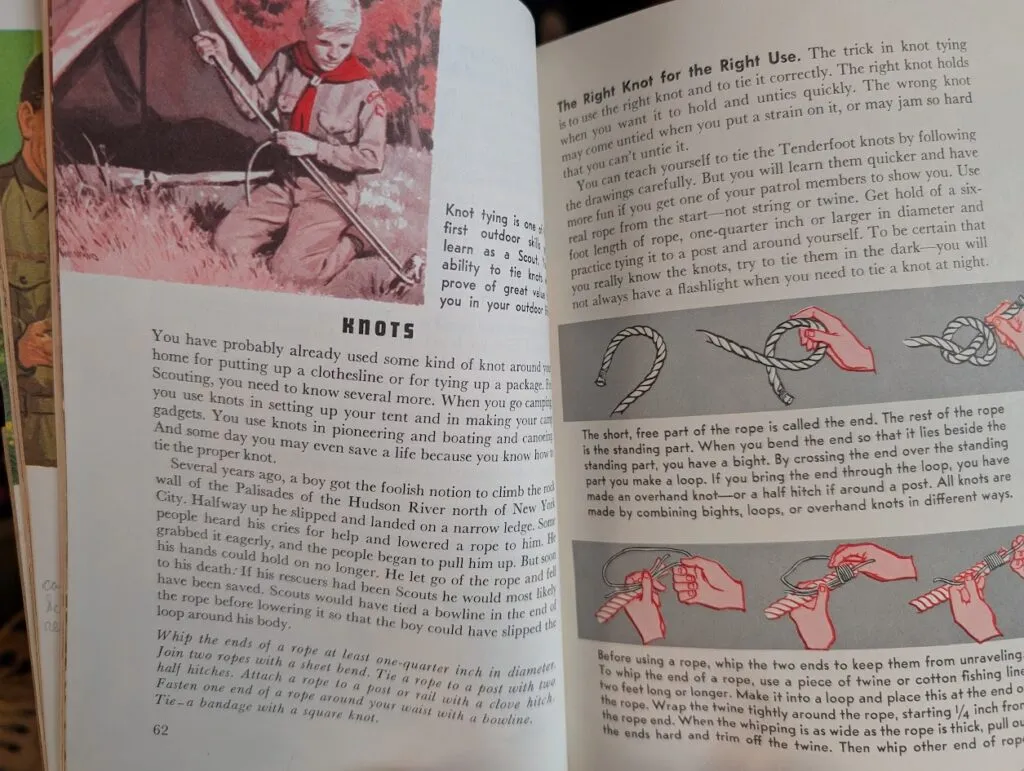

The handbook was beautiful. Clear illustrations. Step-by-step instructions. Safety procedures. Knot-tying techniques. First aid protocols. Fire-building methods. It all made sense on the page. The world the handbook described was orderly, predictable, constraint-based. Do these steps, get these results.

But operational reality didn’t always match the handbook. Not because the handbook was wrong, but because it described ideal conditions. The friction bow fire-starting technique works beautifully when you have dry wood, proper technique, and patience. It works less beautifully when you’re cold, the wood is damp, and you’re trying to get a fire started before dark. The handbook told you what should work. Experience told you what actually worked in degraded conditions.

Author’s Note: My copy of this handbook is the 1959 edition, though I read it decades later. Even as a kid, I noticed a jarring delta between the illustrations and the reality on the ground.

In the book, the uniform is depicted as essential utility gear: worn completely, correctly, and rigorously by everyone, even while building bridges or hiking. In my actual experience, even at large multi-troop gatherings, almost no one possessed a complete uniform, and absolutely no one wore it as “utility” gear in the field.

For years, I chalked this up to “times changing.” I assumed that in 1959, the operational reality matched the book. But looking back through the lens of Regime Recognition, I wonder if that was ever true.

It is likely that the handbook always functioned as an aspirational document (a description of a Constraint-Based Ideal) while the actual scouts on the ground always operated in an Exception-Based Reality of mismatched socks, lost neckerchiefs, and practical adaptation. The gap isn’t time; the gap is the difference between the map and the terrain.

It wasn’t until much later in life that I learned to look at people’s behaviors instead of just their stated rules. Actions really do speak louder than words, especially when you’re transitioning from a constraint-based environment to an exception-based environment.

The transition happened gradually. Small operational experiences where the handbook approach didn’t work. Situations where following the procedure precisely would have failed, but adapting based on observed patterns succeeded. Watching experienced people violate handbook protocols systematically and get better outcomes than the handbook predicted.

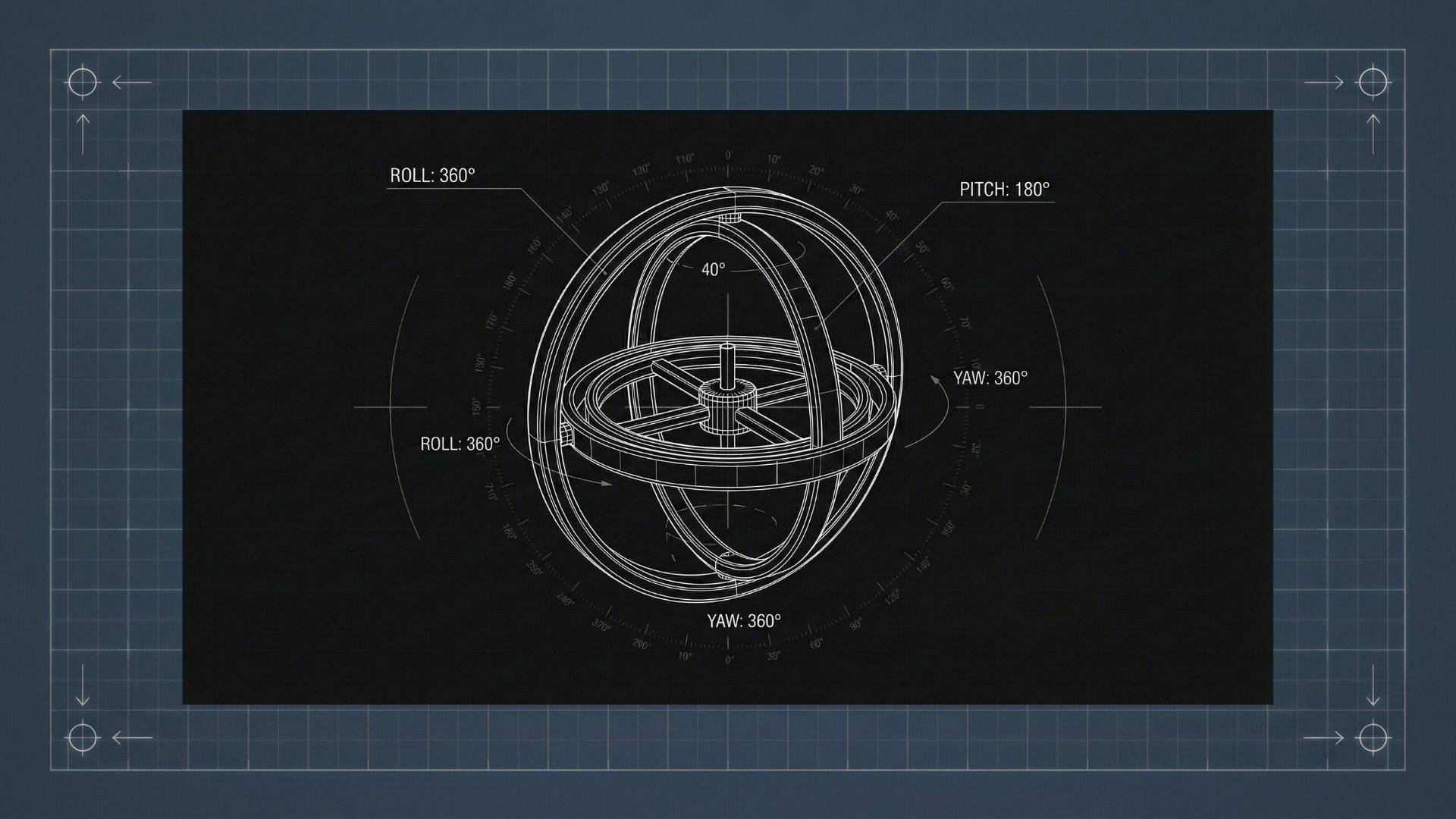

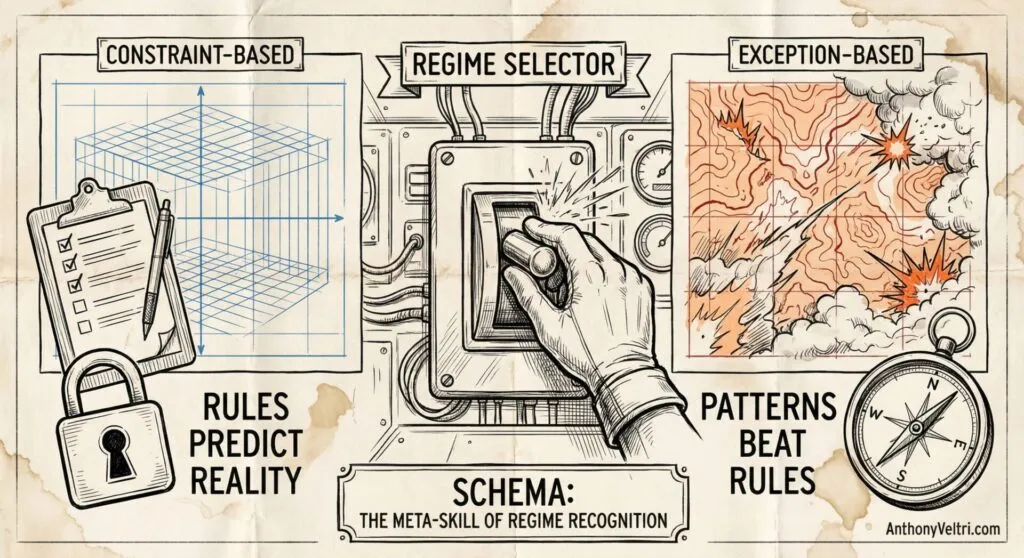

This is the distinction between constraint-based and exception-based environments that I had to learn operationally:

In a constraint-based environment, the rules describe what will happen. Violations are rare. The handbook maps to reality. Boy Scout training for knife safety, for instance. You teach proper grip, cutting direction, safety zones. The physics of sharp objects and human flesh are highly constrained. The handbook accurately predicts outcomes. Following the protocol prevents injuries. Theory-first learning works because the theory describes operational reality.

In an exception-based environment, the rules describe what should happen, but actual behavior may diverge systematically. The handbook becomes aspirational rather than descriptive. Wildland fire operations have procedures, but fire doesn’t follow procedures. Disaster response has mutual aid agreements, but disasters don’t respect jurisdictional boundaries or communication protocols.

I applied the same level of vigor to learning how to identify patterns of behavior as I did to memorizing the handbook. These are two different skill sets for two entirely different regimes (and by regime I mean set of circumstances, not political systems). But you can’t just know both. You have to recognize which regime you’re operating in and which analytical framework to apply.

The Boy Scout Handbook taught me constraint-based thinking. Operational experience taught me exception-based pattern recognition. The watershed moment wasn’t learning one was superior. It was learning to identify which regime I was operating in and applying the appropriate framework.

The Dangerous Gaps: Too New or Too Experienced

There’s a counter-argument I need to address directly. Post-hoc learning can perpetuate bad habits because you didn’t learn the correct technique from the start. This is true. Sometimes critically true.

Think about aviation. The most dangerous pilots are the ones who are so new that they haven’t learned how to effectively operate the aircraft and use the checklist yet. They have some capability, but not enough discipline or formal training to operate safely. The other, much smaller group, are those pilots who are so experienced that they don’t believe they need the checklist anymore. They’ve internalized the patterns so thoroughly that they start skipping formal verification steps. Both gaps kill people.

Pilot training is very strict and regulated for exactly this reason. The entry path is controlled. You don’t just pick up a plane and learn by trying. You go through structured training that combines theory and practice in a specific sequence designed to prevent catastrophic failure modes.

The same applies to firefighter training, surgical residencies, structural engineering licensure, and other high-consequence domains. For certain things, yes, it’s very important to have a very defined learning path. You can’t just “figure out” how to perform surgery through practice-first learning. The consequences of bad habits are too severe.

But here’s the thing: most things people learn in their daily lives are not run like pilot training or firefighter training.

Most people who learned to use a chainsaw outside of shop class or outside of a forestry program probably aren’t doing it “by the book.” They learned from a neighbor, a family member, YouTube videos, trial and error. They might have developed bad habits. They might be holding it wrong, making dangerous cuts, or skipping safety protocols. Post-hoc learning the formal technique might reveal those bad habits, but it might also be too late. The patterns are already internalized. Note: Practice-First learning often has a higher “tuition cost” (minor injuries/failures) in exchange for deeper operational reality. Also, there is some survivor bias here, as we aren’t hearing from those who did suffer a grave injury as a result of not learning it by the book.

This is the legitimate criticism of practice-first learning. Without structured entry, you might develop operational patterns that work (you haven’t cut your leg off yet) but aren’t safe or optimal. You might not even know what you don’t know.

But here’s what the theory-first advocates miss: you come in midway to a lot of things. Most adult learning happens on the job, in context, without formal training pathways. Unless you’re learning to fly an airplane or become a firefighter, you’re often introduced to something midway through. You’re not treated as a beginner. You’re expected to pick it up and contribute.

My first disaster response wasn’t preceded by formal disaster response training. I learned in the moment, from people who were learning in the moment, during an actual emergency. My first federation architecture problem wasn’t solved after completing a formal course on distributed systems. I was handed the problem and expected to solve it with whatever tools and knowledge I could bring to bear.

This is how most operational knowledge gets transferred. Not through structured learning paths, but through on-the-job exposure with post-hoc formalization if you’re lucky enough to encounter it later.

Sometimes Handles-First Is Actually Correct

There’s another nuance here. Sometimes it IS appropriate to get the handles first, before the live tools.

Teaching a Boy Scout proper knife or ax safety can be done with the handles. You don’t need the live blade to learn the safety principles and techniques. You can practice proper grip, cutting motion, safety zones, body positioning with a training tool that won’t actually cut you. Then, once you’ve internalized the safety protocols, you transition to the live blade.

This is handles-first learning done right. The theory (here’s how to hold the knife safely) precedes the practice (now hold the actual sharp knife) because the consequences of getting it wrong are severe and immediate.

But even in this case, the handles-first approach only works because the theory accurately maps to operational reality. The physics of sharp objects don’t change. The safety protocols describe what will actually happen if you violate them. This is constraint-based learning in a constraint-based domain.

The problem with theory-first learning isn’t that it’s always wrong. The problem is applying it universally, including to exception-based domains where the theory doesn’t accurately describe operational reality.

The Kanban Space: Organization Adds Utility

When I said post-hoc learning gave me handles and a way to organize them kanban-style, I mean something specific.

Having the formal term doesn’t just give you a handle for an individual tool. It gives you a place for that tool in an organized system. The handle makes the tool fit in the kanban space, which provides an organized storage and retrieval system.

Before I had the formal vocabulary, I had operational capabilities scattered across my experience. I could solve federation problems, but I didn’t have a framework for organizing federation solutions. I could identify pattern-matching in my own decision-making, but I couldn’t explain it to someone else. I could operate effectively in exception-based environments, but I didn’t have language for why my approach differed from handbook-thinking.

Post-hoc, learning the formal terms did several things:

1. Organization: The vocabulary let me see which capabilities belonged together. “Federation” and “integration” aren’t just two words, they’re organizing principles for an entire class of architectural decisions.

2. Retrieval: When someone describes a problem, the formal vocabulary lets me quickly identify which tool applies. “That sounds like a federation problem, not an integration problem” retrieves the relevant operational patterns.

3. Connection: The formal frameworks revealed connections between domains I thought were separate. Federation principles in disaster response map to federation principles in software architecture map to federation principles in organizational design.

4. Transfer: The handles make the tools transferable. I can’t hand you my operational experience. But I can teach you the formal framework and help you develop your own operational patterns within that structure.

This is why the kanban metaphor matters. It’s not just about having tools. It’s about having organized tools that you can retrieve when needed and explain to someone else. The formal vocabulary is the labeling system that makes the kanban board work.

Without handles, I had a garage full of loose tools. Useful if I knew exactly what I needed, but hard to explain to someone else and hard to retrieve quickly under pressure. With handles and formal organization, I have a kanban board. Everything has a place. I can find what I need quickly. I can show someone else where things are and how they relate to each other.

That organizational utility is separate from the operational utility. The tools worked before I had handles. But the handles made them transferable and systematically accessible rather than buried in tacit knowledge.

When to Go Back and Learn Theory

So when should you go back and learn the formal theory after you’ve developed operational mastery? Not always. Sometimes the operational patterns are sufficient.

You should go back and learn theory when:

1. You need to teach others

If you’re going to transfer knowledge, formal vocabulary is the compression layer. You can demonstrate techniques, but without formal frameworks, people can’t abstract beyond your specific examples.

2. You’re encountering systematic failure patterns

If your operational approach works 80% of the time but fails unpredictably, formal theory might reveal what you’re missing. The framework can show you blind spots that operational experience hasn’t exposed yet.

3. You’re crossing into higher-consequence domains

If the stakes are increasing (more people affected, higher costs of failure, safety-critical applications), formal theory helps identify failure modes you haven’t encountered yet. This is the pilot checklist problem. Experience isn’t enough when the consequences are catastrophic.

4. You’re collaborating with formally-trained practitioners

If you need to work with people who learned theory-first, speaking their language improves coordination. You might have better operational intuition, but they might have frameworks that help structure the collaboration.

5. You’re trying to innovate beyond your operational experience

If you need to extrapolate to novel contexts, formal theory provides abstractions that might generalize better than your specific operational patterns. Theory can suggest possibilities your experience hasn’t encountered.

You probably don’t need formal theory when:

1. Your operational patterns are working consistently

If you’re solving the problems effectively and you’re not trying to teach others or scale your approach, handles might not add value. The tools work fine without formal organization.

2. The domain changes faster than theory can keep up

Some fields move so quickly that formal frameworks lag behind operational practice. Tech is often like this. Practitioners figure out what works, then academics formalize it years later. Learning the outdated theory doesn’t help.

3. The theory doesn’t map to your operational reality

If the formal frameworks describe idealized conditions that don’t match your actual context, learning them might constrain your thinking rather than expanding it. Sometimes operational knowledge is more accurate than academic knowledge.

4. You’re in a pure execution role with no teaching requirement

If you’re just doing the work and not transferring knowledge, post-hoc formalization might be unnecessary overhead. The handles don’t make the tools work better, they just make them transferable.

Here’s the key insight: for most adult learning, you’re introduced midway through. You’re not starting from a clean slate with structured training. You’re expected to contribute immediately, learn on the job, and formalize later if it becomes necessary.

The German language learning made this clear. I needed conversational capability immediately for travel and communication. I couldn’t wait to complete a formal grammar course before trying to speak. I learned enough to function, then went back and learned the formal structure when I realized I wanted to teach my kids or write more precisely.

The post-hoc formalization happened when I needed transferability and organization, not when I needed operational capability. The operational capability came first because that’s what the mission required.

This is why dismissing post-hoc learning as “perpetuating bad habits” misses the operational reality. Yes, sometimes you develop bad habits. Yes, sometimes those habits cause problems. But often, the alternative isn’t “learn theory-first with perfect technique.” The alternative is “don’t learn at all because no formal training pathway exists or is accessible.”

Most chainsaw users learned from whoever was willing to show them. Most disaster responders learned during disasters from other people learning during disasters. Most practitioners in most fields learned midway through, with incomplete context, from people who also learned midway through.

Post-hoc formalization is the mechanism for systematically improving that operational knowledge base. Not by replacing it with theory, but by adding formal organization and transfer mechanisms to capabilities people have already developed through practice.

Schema: When Each Mode Works

But stepping back, when does each learning mode actually work? Let me map this more clearly, because there are contexts where theory-first is the right approach and contexts where it’s catastrophically wrong.

| Feature | Constraint-Based Regime | Exception-Based Regime |

| Operational Reality | The rules describe what will happen. | The rules describe what should happen. |

| The Handbook | Descriptive: Maps accurately to reality. | Aspirational: Describes an ideal state; ignores friction. |

| Violations | Rare, noteworthy, and usually an error. | Systematic, frequent, and often necessary for success. |

| Learning Mode | Theory-First: Learn the rules, then apply them. | Practice-First: Develop pattern recognition, then formalize. |

| Failure Mode | Innovation Risk: “We’ve always done it this way.” | Chaos Risk: “Bad habits become permanent.” |

| Examples | Aviation, Manufacturing, Structural Engineering. | Wildland Fire, Disaster Response, Natural Language. |

Constraint-Based Environments (Theory-First Works)

- The rules describe what will actually happen

- Violations are rare and noteworthy

- The handbook maps to operational reality

- Formal training provides accurate mental models

- Examples: established manufacturing processes, well-regulated industries, stable technical domains

In constraint-based environments, learning the theory first is efficient. The framework is accurate. The rules predict outcomes. You can study the manual and then apply it with confidence that reality will match the description.

Exception-Based Environments (Practice-First Essential)

- The rules describe what should happen, but behavior diverges systematically

- The handbook is aspirational rather than descriptive

- Operational reality doesn’t match formal frameworks

- Pattern recognition beats rule-following

- Examples: disaster response, wildland fire operations, conversational language use, federation problems

In exception-based environments, the formal frameworks don’t match what you encounter operationally. You need to develop pattern recognition through practice, then learn the formal vocabulary post-hoc to organize and transfer what you’ve learned.

The Meta-Skill: Regime Recognition

But you can’t just know both learning modes. You have to know which environment you’re in and which approach to apply.

The meta-skill isn’t just knowing both frameworks. It’s regime recognition: identifying which kind of environment you’re in and applying the appropriate analytical approach. Going into a constraint-based planning meeting with exception-based thinking makes you look paranoid. Going into an exception-dominated operational environment with constraint-based thinking gets people hurt.

I learned this the hard way. I spent years trying to apply handbook logic to situations where the handbook didn’t describe reality. It wasn’t that I didn’t know the handbook. It was that I didn’t recognize I was in a regime where the handbook was aspirational rather than descriptive. Once I learned to identify the regime first, I could choose the right analytical framework. Constraint-based when constraints hold. Exception-based when they don’t.

This is also why learning language through immersion rather than formal study works better for me now. Formal Spanish instruction was constraint-based: here are the rules, apply them. But conversational language use is exception-dominated: native speakers violate formal rules constantly, idioms don’t follow grammar logic, context determines meaning. I was trying to apply constraint-based learning to an exception-based domain.

Immersion with German, French, and Italian forces exception-based learning first. I encounter violations of the “rules” constantly. Then I learn the formal grammar post-hoc as the constraint framework that describes the aspirational standard. But I already know how people actually speak, which is the operational reality I need to function in.

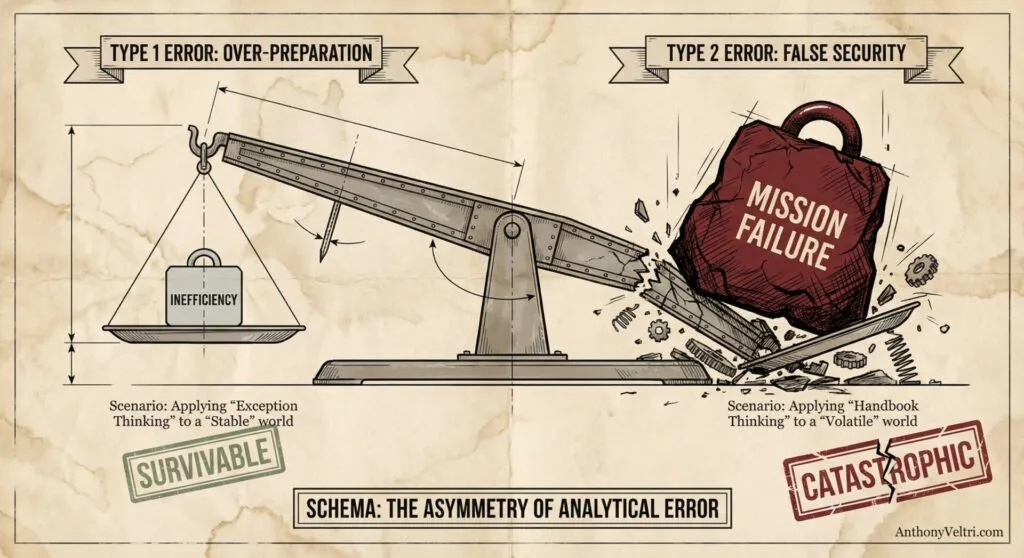

Asymmetric Error Costs

The failure modes have different consequences depending on which mistake you make.

If you apply exception-based pattern recognition in a constraint-heavy environment, you’re going to get a lot of noise and not much signal. You’ll see threats that aren’t there. You’ll over-complicate simple situations. You’ll waste resources preparing for violations that won’t occur. This is inefficient, but it’s not catastrophic. You’re over-prepared for a stable situation.

On the other hand, if you apply constraint-based thinking to an exception-dominated environment, you’re setting yourself up for catastrophic failure. You assume the rules will hold. You plan based on what “should” happen according to the handbook. When reality violates your assumptions, you’re not just unprepared, you’ve built your entire response on false premises.

Example: During disaster response, assuming mutual aid will arrive on schedule because that’s what the plan says. The plan is constraint-based. It describes what should happen in an orderly world. But disasters are exception-dominated environments. The roads might be impassable. The mutual aid jurisdiction might be dealing with their own emergency. Communications might be down. If you plan as though the constraints will hold, you’ve just created a single point of failure in your entire response.

The asymmetry matters. Mistaking an exception-based environment for a constraint-based one is more catastrophic than the reverse. False negatives (missing real exceptions, assuming rules will hold when they won’t) cause mission failure. False positives (seeing exceptions that aren’t there, over-preparing for a stable environment) just cause inefficiency.

This is why most of my operational work has focused on exception-based environments. Disaster response. Wildland fire operations. Federation problems that emerge because integration policies assume constraints that don’t actually constrain. These are contexts where handbook-thinking fails and pattern recognition becomes survival-critical.

Building Infrastructure for Multiple Learning Modes

My wife thinks the routes on my website are the most useful feature. Not the doctrine volumes, not the comprehensive frameworks, not even my favorite field notes. The routes. Because they look good visually, and because they help her solve a specific problem via an identified path.

She wants to learn how to light a fire with a friction bow and how to cook over coals. There are sections in that 1960s Norman Rockwell handbook that show exactly that. She doesn’t need to read the whole handbook. She needs those two sections, right now, for this specific purpose.

She notes that it’s unusual for someone like me (someone who wants to read the whole handbook and maybe even live by it too much) to also recognize that other people don’t learn that way. Hence the routes. Hence the bi-directional figure search. Hence building infrastructure that serves both the comprehensive learners and the just-in-time problem solvers.

I’m a “read the whole handbook” person who learned to build for “solve this specific problem right now” people. That recognition came from operational experience, not from theory. I watched people bounce off comprehensive documentation. I watched them search for targeted solutions. I built the infrastructure to serve both modes.

This connects to the post-hoc learning pattern. Some people need theory-first. They’re operating in constraint-based domains where the handbook maps to reality. Learning the framework first is efficient for them.

Other people need practice-first with post-hoc formalization. They’re operating in exception-based domains where the handbook doesn’t describe operational reality. They need to develop the tools through use, then learn the handles later.

The infrastructure I’ve built tries to serve both. The doctrine volumes for the handbook readers. The routes for the just-in-time problem solvers. The field notes for people who learn through operational narratives. The figures for people who think visually.

When Post-Hoc Learning Is Actually Superior

Post-hoc learning isn’t just “acceptable when theory-first fails.” In certain contexts, it’s actually the superior learning path.

When you learn theory-first, you’re constrained by the framework. You see problems through the lens the framework provides. You apply solutions the framework suggests. If the framework is accurate, this is efficient. If the framework is incomplete or wrong, you’re trapped.

When you learn practice-first, you develop pattern recognition unconstrained by formal frameworks. You see what actually works. You identify solutions the handbook didn’t anticipate. Then when you learn the theory post-hoc, you can evaluate which parts of the formal framework map to your operational experience and which parts are academic artifacts.

The German grammar I’m learning now makes sense because I can map it to patterns I’ve already internalized. When I learn about the dative case, I immediately recognize it as the formal description of something I’m already doing correctly. I can evaluate whether the “rule” actually describes usage or whether it’s an oversimplification.

Someone who learned German theory-first would have the opposite problem. They’d know the rule, but they wouldn’t necessarily recognize when native speakers violate it or why. The framework would constrain their understanding rather than organizing it.

This advantage shows up in operational work constantly. I learned federation versus integration through solving federation problems for years. When I finally encountered the formal terminology, I could immediately see which aspects of the academic frameworks matched my operational experience and which aspects were theoretical constructs that don’t survive field contact.

Someone who learned the federation theory first might implement solutions that follow the academic framework but fail operationally because the framework doesn’t account for real-world constraints.

Post-hoc learning lets you validate theory against practice instead of assuming theory describes practice.

The Fitted Handle Moment

When I started dreaming in German, I realized I’d crossed a threshold. The language wasn’t something I was translating anymore. It was something I was thinking in. The formal grammar I learned afterward didn’t create that capability. It gave me handles for organizing and explaining capability I’d already developed.

Those handles did more than just label the tools. They gave each tool a place in the kanban system. I could retrieve them when needed. I could show others where they were. I could see which tools belonged together and which solved different classes of problems.

That’s what post-hoc learning provides: not the tools, but the fitted handles and the organizational system. Not the capability, but the transfer mechanism and the retrieval structure. Not the operational mastery, but the framework that lets you teach what you know and systematically access what you’ve learned.

I’m finally learning English grammar now, during my study of German, Italian, and French. I can use verb tenses and cases properly in English. But I didn’t know what they were called until now. The theory-first critic would say I spent decades using my native language sub-optimally.

But I was using English correctly the entire time. I had operational fluency. The formal terminology didn’t make me better at English. It gave me the ability to analyze and teach what I was already doing correctly. It gave me compression and abstraction tools for knowledge transfer. It gave me a kanban board for organizing language concepts I’d been using without formal structure.

That’s the watershed moment. Not “I finally learned the right way to do this.” But “I finally learned how to organize what I’ve been doing all along, and how to explain it to someone else.”

Yes, sometimes post-hoc learning perpetuates bad habits. Yes, sometimes those habits cause problems. But the alternative isn’t always “learn theory-first with perfect technique.” Often the alternative is “don’t learn at all because no formal pathway exists.” Or “stay operationally incompetent because the theory doesn’t map to reality.”

The handles don’t make the tools work. But they make the tools transferable, explainable, and organizeable. They unlock the ability to communicate with people who learned differently than you did. They let you participate in formal discourse without abandoning operational validity. They give you a kanban board instead of a pile of loose tools.

Theory-first gives you handles without tools. Practice-first with post-hoc formalization gives you tools first, then fitted handles and organizational systems. In constraint-based environments where theory accurately describes reality, handles-first might be more efficient. In exception-based environments where the handbook is aspirational, tools-first is often the only path to actual capability.

The criticism that post-hoc learning is “backwards” assumes one learning sequence is universally superior. My operational experience proves otherwise. Sometimes you need to master the tools handleless before you can appreciate what the handles provide. Sometimes the formal framework only makes sense after you’ve internalized the operational patterns it attempts to describe. And sometimes you enter midway through with no formal training option, and post-hoc formalization is the mechanism that systematically improves practice-based learning.

I’m not arguing everyone should learn my way. I’m arguing that dismissing post-hoc learning as inferior ignores the operational evidence, the regime-dependent nature of learning effectiveness, and the reality of how most adult learning actually happens. The sequence matters less than the outcome: can you execute effectively, can you identify when your approach is failing, and can you transfer that capability to others when transfer becomes necessary?

When I dream in German now, the grammar terminology isn’t translating for me. It’s organizing concepts I’ve already internalized. That’s what post-hoc learning provides. Not translation, but organization. Not capability, but transferability. Not the tools, but the fitted handles and the kanban board that makes them systematically accessible.

The fitted handle moment is when you realize the formal vocabulary isn’t teaching you the thing. It’s giving you the infrastructure to teach the thing to someone else, and to organize your own capabilities so you can retrieve them when needed. That’s not backwards. That’s just a different sequence with different advantages depending on which regime you’re operating in and which phase of mastery you’re navigating.

Last Updated on February 20, 2026