Sphere and Spikes: Building What You Need Without Becoming a Specialist

Competent Enough to Know What to Learn Next

The Photo Distribution Problem

There’s a GoPro time lapse somewhere in my files showing (found it!) three hours of work compressed into ninety seconds. My wife and I are standing over a drafting table that used to belong to Princeton University (still has the brass plate), spreading out school photos and trying to figure out who gets what envelope.

Three hours of work, compressed to 90 seconds (silent time lapse). Matching student photos to family distribution packets when one parent might have three kids and one child might have two parents at different addresses. Excel couldn’t think relationally. We apparently couldn’t either, so we spent an afternoon wearing nitrile gloves over a drafting table that used to belong to Rutgers.

The problem was simple to state and infuriating to execute: get the right photos to the right families. But families don’t organize neatly. Some parents have one kid, some have three. Some kids have one parent picking them up, some have two parents at different addresses, some have a grandparent or guardian in the mix. I needed to produce a distribution list that answered one question: who needs to receive a photo packet, and which kids’ photos go in it?

Most people in my situation would have delivered a box of photos to the school and let them sort it out like a lost and found that gets cleaned out at the end of the year. That would have been easier. But I knew these photos meant something to those parents, and I’d put real work into creating them. I wasn’t going to see them distributed willy-nilly or end up unclaimed in some bin. Proper stewardship meant getting them to the right people, even if that meant hours of sorting work over a drafting table.

Excel fought me the entire way.

I ended up with some combination of VLOOKUP functions and pivot tables and probably a few desperate concatenation formulas, building queries that would tell me which parents were connected to which children and vice versa. It worked, barely, but maintaining it was an awkward balancing act. Every time I needed to check something, I was rebuilding the same relationship logic: show me all parents connected to this child, show me all children connected to this parent. The data existed. Excel just didn’t want to think relationally.

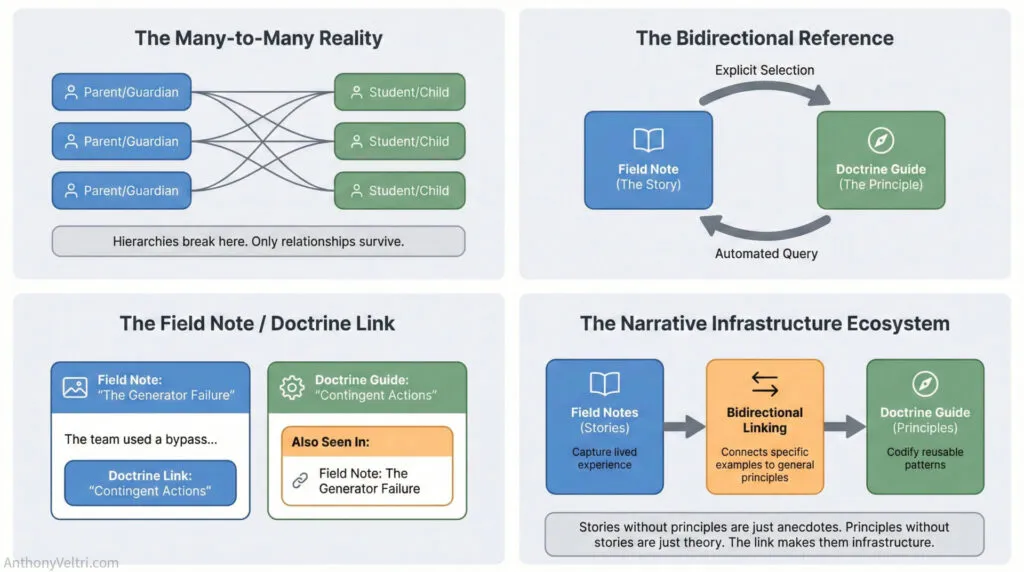

What I didn’t realize at the time was that I’d just learned how many-to-many relationships work by brute force trial and error. One parent, many children. One child, many parents (or caregivers). The relationship goes both ways, and you need to be able to query it from either direction. This is basic relational database stuff, but I wasn’t thinking in those terms. I was just trying to distribute photos without driving myself insane.

The Same Pattern, Different Domain

Fast forward a few years. I’m building a documentation system for the work I do, mission architecture and systems doctrine. I’ve written over twenty doctrine volumes, a dozen formal annexes, and I’m generating field guides (these blog posts) that document real-world applications of the principles. The whole point of the system is to connect theory to practice: doctrine entries contain principles, field guides describe how those principles played out in actual stakeholder situations or crisis response or infrastructure decisions.

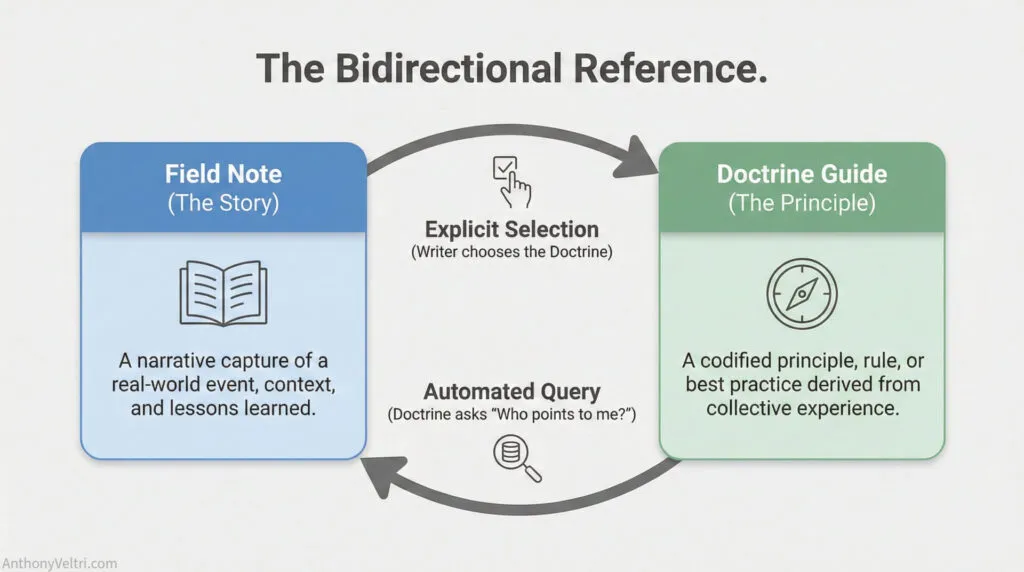

But I kept running into a problem. When I’m writing a field guide about some coalition-building challenge I faced, I want to reference the relevant doctrine principles. That’s the easy direction: field guide points to doctrine. But I also want someone reading a doctrine entry to see which field guides demonstrate that principle in action. That’s the reverse direction: doctrine points back to field guides. And one field guide might reference multiple doctrine entries, while one doctrine entry might be demonstrated across multiple field guides.

Sound familiar?

It’s the photo distribution problem again. Same structural pattern, different domain. Many-to-many relationships that need to be navigable from both directions.

Building the Infrastructure

This time I didn’t use Excel.I’m working in WordPress, and I knew there were tools that could handle this kind of relationship. I found Advanced Custom Fields, which has a relationship field type built specifically for connecting content types.

Here’s what I built: every field guide has a relationship field where I can select which doctrine entries or annexes it references. That’s the forward link, the easy direction. But then I wanted the doctrine pages to automatically display a list of all field guides that reference them. That’s the reverse query: show me everything that points to this item.

I solved it with a custom shortcode that queries the database: find all field guides where the relationship field includes this doctrine entry’s ID, then display them as a list. The shortcode sits at the bottom of every doctrine page, and it updates automatically whenever I publish a new field guide that references that doctrine. I don’t maintain the list manually. The relationship structure does the work.

Under the hood, this is conceptually similar to an inner join in SQL (which I’d learned for a different project entirely). You’re connecting two tables based on shared values and displaying the results. But I didn’t need to write SQL queries manually because ACF handles the database relationships at a higher level of abstraction. I just needed to know what needed to exist: bidirectional reference display that updates automatically.

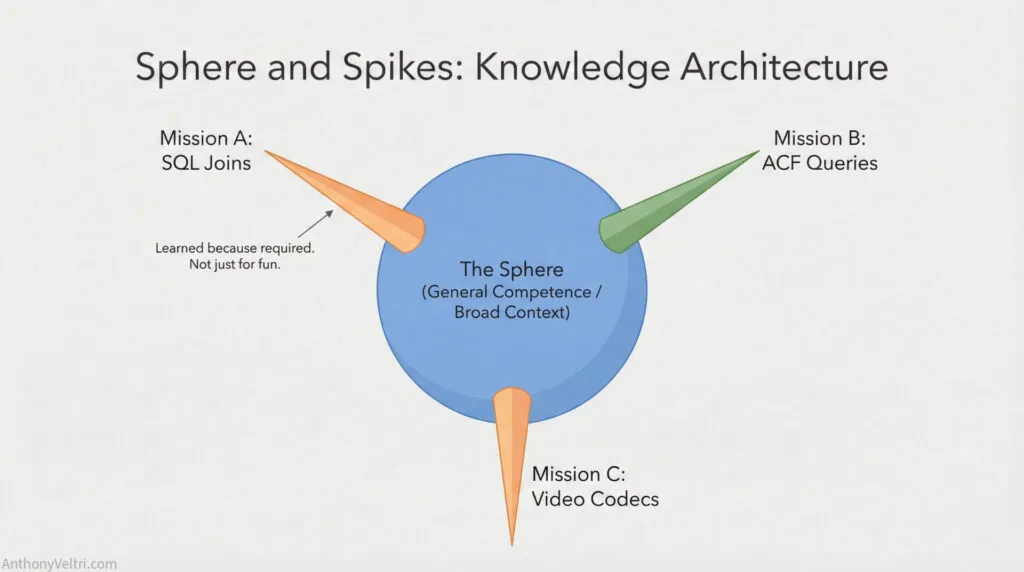

What I Couldn’t See for Myself

The sphere-and-spikes pattern is this: I maintain general competence across a technical domain (WordPress administration, database basics, query logic), but when a specific mission requirement appears, I drill down vertically into exactly what’s needed. I learned inner joins for one project because that’s what the requirement demanded. I learned ACF relationship fields for another project for the same reason. I didn’t systematically study database design. I learned what the mission required, then returned to the surface.

The spikes are evidence that the requirement was real. If you look at my knowledge map, you’d see broad shallow coverage across web infrastructure with sharp vertical spikes into inner joins, ACF relationship queries, WordPress shortcode development, custom schema creation. Each spike exists because I needed to build something specific and the baseline knowledge wasn’t enough. The mission drove the learning.

What makes this worth documenting (and what I couldn’t see myself until someone pointed it out, classic Johari window territory) is that the photo distribution problem taught me relational thinking without me realizing I was learning it. When I hit the same structural pattern years later in the documentation system, I recognized it immediately: this is a many-to-many relationship problem, I need tooling that handles this natively, Excel is the wrong tool, what’s the web equivalent?

I wasn’t starting from zero. I’d already fought this battle with school photos. I knew what the end result needed to look like because I’d prototyped it (miserably) in Excel. When I discovered ACF could handle those relationships without the pivot table nightmare, I knew exactly what to implement.

The field guide lesson here isn’t “learn ACF” or “learn SQL” or “master relational databases.” It’s that mission requirements are better teachers than curriculum. If you know exactly what needs to exist, you can reverse-engineer just enough technical knowledge to make it happen. You stay in your zone of proximal development because the requirement is clear and bounded.

I’m not a developer. I don’t write code for a living. But I’ve built real knowledge infrastructure because I had a clear picture of what needed to exist and I was willing to learn whatever technical constructs stood between me and that requirement. Sometimes that’s inner joins. Sometimes it’s ACF relationships. Sometimes it’s probably something I haven’t encountered yet, but when I do, I’ll have enough baseline competence to recognize what kind of spike I need to grow.

The drafting table is still in the kitchen. We don’t use it for photo sorting anymore, but we kept it because sometimes you need a big flat surface to spread things out and see the relationships clearly. That’s true for school photos and it’s true for documentation systems and it’s probably true for whatever comes next.

Why This Pattern Matters

The sphere-and-spikes approach has emergent properties that aren’t obvious until you’ve been working this way for a while. Understanding these properties helps explain why this pattern persists (it works operationally) and where it creates friction (evaluation contexts that expect systematic knowledge).

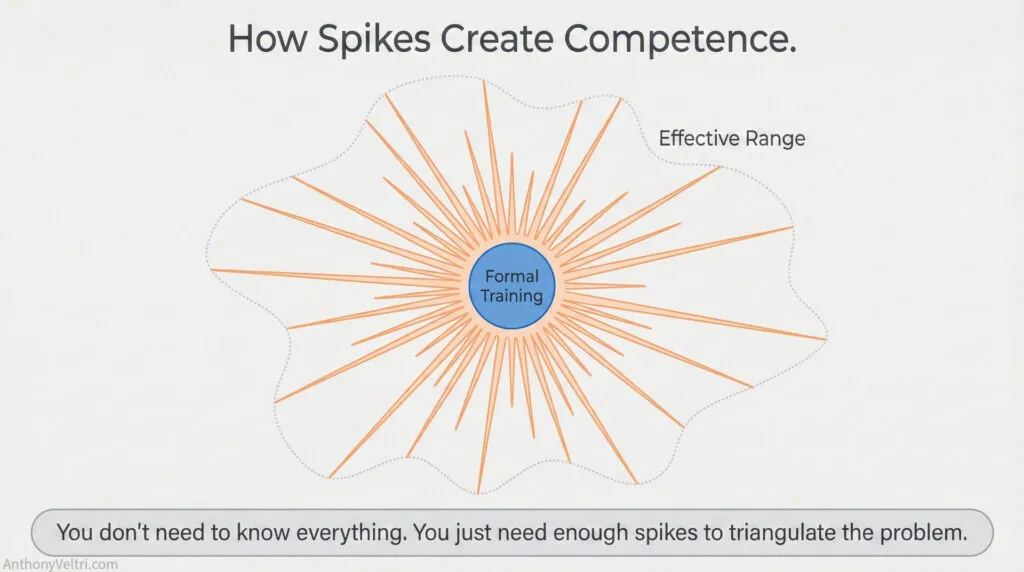

The Spike as Doorstop

Each spike wedges open adjacent territory you didn’t explicitly learn. When I learned inner joins for one specific requirement, I also gained conceptual access to outer joins, left joins, and relationship logic more broadly. The spike gives you leverage into neighboring concepts even though you only drilled down in one spot. You can reason about adjacent problems even if you haven’t formally studied them.

This is different from comprehensive study, where you learn things in systematic order. With spike learning, you enter from an unexpected angle (a specific mission requirement) and then discover you can navigate nearby territory because you understand the underlying logic. The spike acts like a doorstop wedged into a conceptual domain, keeping it accessible even after you return to baseline.

Multiple Spikes Approximating a Larger Sphere

Here’s where it gets interesting. If you have enough mission-driven spikes (inner joins, ACF relationships, WordPress shortcodes, custom schema design), collectively they start to create fuzzy competence across a broader domain. I don’t have systematic SQL knowledge, but I have enough spikes into database operations that I can navigate most database scenarios. The spikes effectively expand my baseline sphere without me having to study comprehensively.

Think of it like this: if you have one spike, you have deep knowledge in one narrow area. If you have ten spikes distributed across a domain, you start to approximate broader competence because the doorstop effect from each spike gives you conceptual access to adjacent areas. The surface between the spikes fills in through operational experience and pattern recognition. The radius of the sphere increases naturally as the spikes accumulate.

Assets of the Spikeball Pattern

This approach has real advantages in operational contexts:

Efficient evidence of capability: Each spike proves you can learn what’s needed under pressure. The spike exists because a mission requirement demanded it, which means you’ve demonstrated the ability to acquire targeted expertise when it matters.

Pattern recognition compounds: The school photos problem taught me relational thinking, which made the ACF spike faster to grow. Each spike makes the next one easier because you’re building meta-learning patterns. You’re not just learning inner joins or ACF relationships, you’re learning how to learn what’s needed.

Creative problem-solving: You often arrive at non-standard solutions because you’re not constrained by “proper” learning sequences. I came at the bidirectional reference problem from the photos angle, not from database theory, which meant I recognized the pattern in a different context than a formally trained developer might.

Adaptive capacity: You can grow new spikes as requirements appear rather than front-loading comprehensive study. This is particularly valuable in fast-moving environments where you can’t predict what knowledge will be needed six months from now.

Liabilities of the Spikeball Pattern

The same properties that make this approach operationally effective create friction in evaluation contexts:

Uneven knowledge creates blind spots: You might have deep inner join expertise but miss basic SQL concepts that everyone else assumes you know. The spikes are sharp but the valleys between them are real gaps.

Evaluation friction: Traditional interviews or certifications expect systematic knowledge. Your spiky profile is hard to assess in artificial contexts. When someone asks “what do you know about databases?” you don’t have a clean answer because you know specific things really well and other things not at all. Your knowledge map is spiky, not smooth.

Communication gaps: You might not know the standard terminology or frameworks others use, even though you can execute the work. You learned what you needed to accomplish the mission, which doesn’t always align with how the domain is formally taught or discussed.

Potential fragility: If a requirement falls between your spikes, you might not recognize you’re missing foundational concepts. The doorstop effect helps with adjacent territory, but there can be areas you simply haven’t touched and don’t know you haven’t touched.

The Evaluation Paradox

Here’s the critical insight: the spikeball approach is operationally superior but evaluatively opaque.

When you’re actually doing the work (building the ACF system, solving the photo distribution problem, architecting federation patterns), the spikes serve you perfectly. Mission requirements pull the right knowledge out of you at the right time. You learn exactly what’s needed, you apply it effectively, you deliver results.

But when someone tries to evaluate your capabilities in an artificial context (panel interview, technical screening, credential review), they’re looking for systematic knowledge. They want to know your overall competence across a domain, and your spiky profile doesn’t fit that assessment model. You can’t easily demonstrate what you know because what you know is distributed across mission-driven spikes rather than organized into formal categories.

The evaluation friction isn’t a bug in your learning approach. It’s a mismatch between how you build capability (mission-driven, incremental, evidence-based) and how organizations try to assess capability (credential-based, comprehensive, decontextualized).

This is why documentation infrastructure matters. Field guides like this one, comprehensive doctrine systems, archived work products, these are evaluation bypass mechanisms. They make capability visible without requiring you to perform pattern recognition on demand in an interview room. Someone can read this field guide, see the progression from photo distribution to ACF relationships, understand that you recognize structural patterns and learn what’s needed, and make an informed decision about your capabilities based on actual work product rather than quiz questions.

The spikeball pattern works. It’s efficient, it’s adaptive, it produces real results. But it requires you to build your own evaluation infrastructure because traditional assessment methods aren’t designed for it.

Technical Notes for the Curious

If you want to replicate the bidirectional reference system:

The relationship field in each field guide is a standard ACF relationship field pointing to the Doctrine and Annexes post types. The shortcode on doctrine pages queries all field guides where that relationship field includes the current post ID, then displays them as a linked list. The query itself is straightforward once you understand you’re looking for “posts of type field_guide where the relationship_field array contains get_the_ID().”

The learning curve isn’t the shortcode syntax (that’s well documented in ACF’s docs). The learning curve is recognizing that you’re solving a many-to-many relationship problem and selecting tools that handle that pattern natively. Once you see the pattern, the implementation is just following documentation.

I prototyped this in Excel first, which was miserable but clarifying. When you’ve built something the hard way, you know exactly what you’re looking for in a better tool.

Last Updated on February 13, 2026