The Scalpel vs. The Swiss Army Knife: When Solo Integration Beats Federation

A refinement of Doctrine 01: Federation vs Integration in Mission Networks

The Conventional Wisdom

Integration is brittle. Federation is resilient.

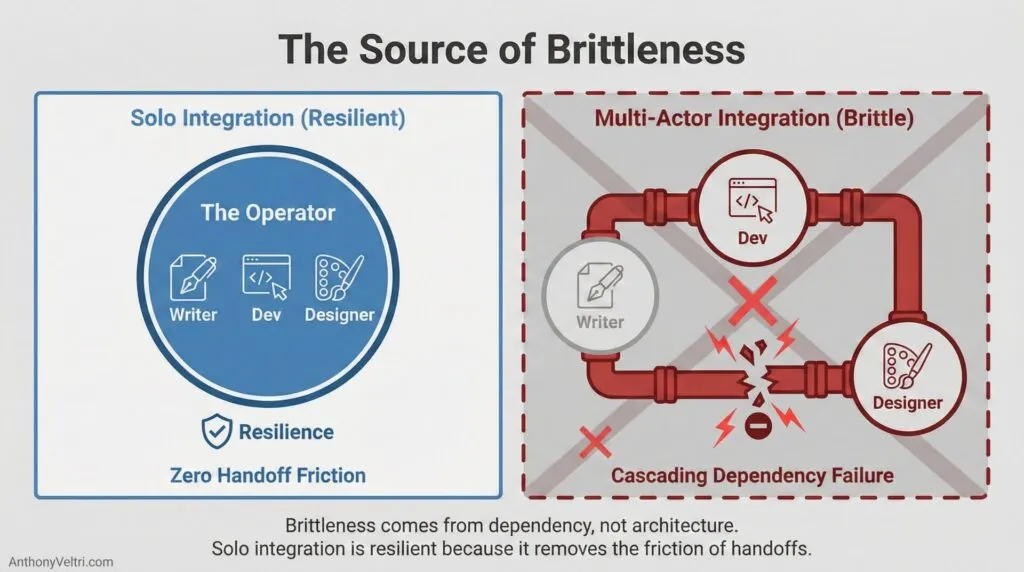

This is what every systems architect learns. Integration creates tight coupling, single points of failure, cascading breakdowns when one component fails. Federation distributes risk, enables graceful degradation, scales more easily across organizational boundaries.

For multi-actor systems, this wisdom holds. But there’s a critical variable most people miss: how many actors are actually in the system.

The brittleness of integration isn’t inherent to the architecture itself. It emerges from multi-actor dependency. When you remove that dependency, the conventional wisdom breaks down.

The Missing Distinction: Actor Count Changes Everything

Think of it this way:

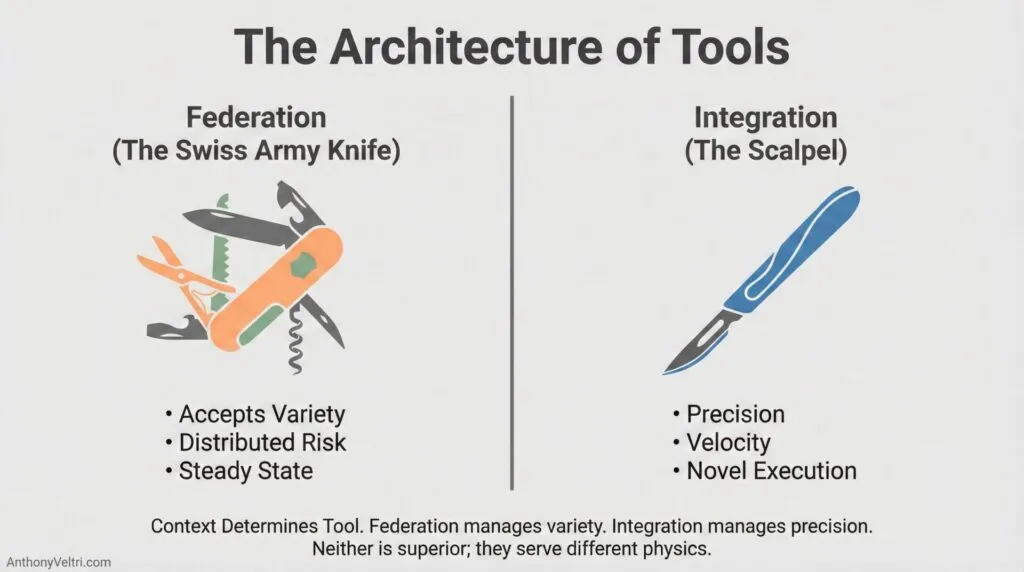

Federation is a Swiss Army knife. It meets everyone where they are. It accepts variety and bears the cost of that acceptance. It scales gracefully because adding new participants doesn’t require re-architecting the whole system. It’s the right tool for steady-state operations where you have training, task books, protocol, and distributed sovereignty.

Integration is a scalpel. It’s the exactly right tool for exactly the right job. It trades flexibility for precision and performance. It’s fragile if misused or applied to the wrong context. It doesn’t scale beyond the operator’s capacity. But in the right hands, for the right surgical operation, nothing else comes close.

The critical question isn’t “integration or federation?” It’s “how many actors, and what kind of work?”

Solo Integration: High Velocity, High Resilience

The 16-day infrastructure sprint that built this documentation platform would have taken an agency 6-9 months. But here’s what that number doesn’t show: I wasn’t learning WordPress from scratch or figuring out relational databases for the first time. I’ve been building e-commerce platforms since 1999, starting with a specialty rock climbing business (bouldering gear) that I ran out of my parents’ garage using Miva Merchant. Back then I was learning vendor relationships, price negotiation, relational databases, and the early Wild West of web development where you could accidentally encode session IDs into URLs and pull up someone else’s shopping cart.

The 16-day sprint was organizing and executing 20 years of accumulated stories, not learning the skills to tell them. The spikes in certain domains (web platforms, database design, content architecture) have grown close enough together that they approximate flat competence. I didn’t hand off between writer, designer, and developer because I’ve been all three for two decades. I wrote the doctrine entry, generated the graphic, configured the WordPress fields, wrote the caption, established the cross-references. All in one flow. No handoffs. No context loss. No waiting.

The difference isn’t the 16 days. It’s the 20 years of learning how not to blunt the scalpel. Specialty tools work not just because you keep them sharp – sometimes they’re disposable because you can’t actually keep them sharp. Your expertise is in using them without dulling or breaking them. Learning to cut without applying torque to the blade. Cutting in a straight line (which seems easy until you try it). Never prying, not even a little bit.

An agency would take 6-9 months because they’d be learning, coordinating, and negotiating handoffs. I took 16 days because I learned over two decades which cuts to make, which work not to take on, and how to deploy integrated capability without breaking it through misuse.

This is overnight capability, not overnight success. The 20 years of learning how not to blunt the scalpel came with costs most people don’t see: the cognitive load of maintaining competence across domains, the isolation of operating in a pattern few understand (try finding someone to help with troubleshooting your ecommerce side business in 1999), the inability to just ‘do your job’ when you see systemic problems others miss. And like the scalpel itself, this capability comes with trade-offs addressed later in this piece – it doesn’t scale, it can harm the operator if overused, and it’s fragile if misapplied.

Where Integration Breaks: Multi-Actor Dependency

The brittleness everyone warns about? It shows up the moment you introduce multiple actors with distributed authority.

Committees are my natural enemy, not because the people are bad, but because they treat execution like a deposition. They represent interests rather than executing work. That is federation energy applied to a context where I am trying to operate integrated, and it grinds everything to a halt. Committees are fine for governance, but fatal for novel execution.

Work projects that require approval chains, compliance frameworks, multiple stakeholder buy-in. All of these force federation whether you want it or not. The velocity drops tremendously compared to personal projects. Not because I’m bad at federation, but because the coordination overhead is real and unavoidable.

This is where integration actually becomes brittle: when you have multiple actors who each hold authority, when sovereignty is distributed, when one person’s delay cascades across the entire operation. If the designer quits, content production stops. If the developer leaves, nothing can ship. If systems are tightly coupled and one person breaks, everything breaks.

The brittleness isn’t the integration architecture. It’s the multi-actor dependency structure underneath.

The Surgical Instrument Pattern

Recognition-primed decision making (RPDM) gives us a framework for when solo integration excels: low frequency, high consequence events. These are the novel operations. The one-time builds. The situations where there’s no task book, no established protocol, no training pipeline.

The Mechanism: Adjacent Synthesis

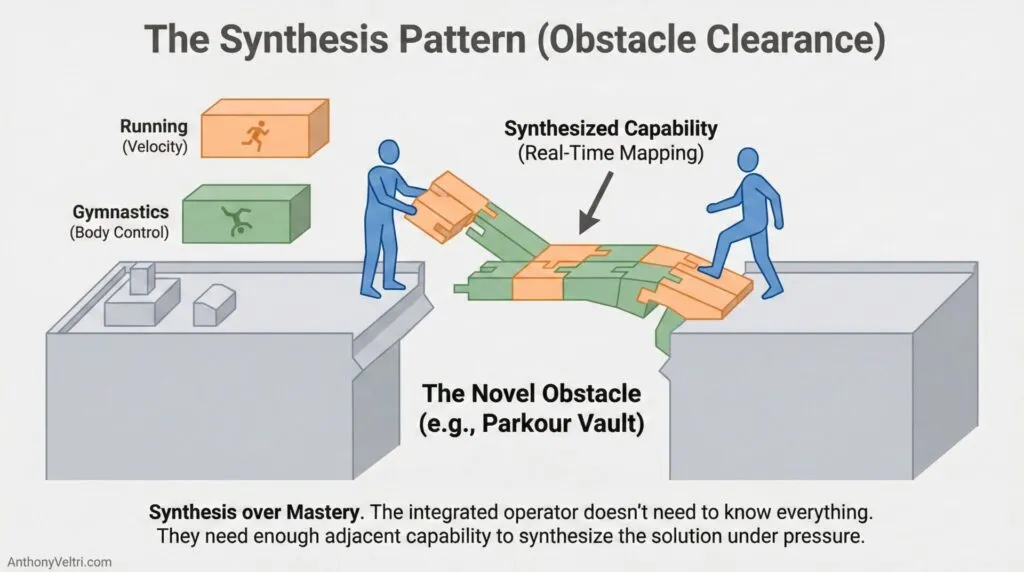

Here’s the critical distinction: You’re facing a 10-foot urban gap, and you don’t know Parkour. But you know Running. You know Gymnastics. You’re very strong with those adjacent skill sets. The mission isn’t about looking like a Red Bull traceur, you just need to make it across the gap.

You don’t need the vocabulary of a ‘kong vault.’ You synthesize the velocity from running and the body control from gymnastics to clear the obstacle. You map the physics of the vault in real-time.”

The integrated operator’s advantage isn’t that they “learn fast.” It is that they synthesize.

You don’t need complete mastery of a new domain before you start. You need enough adjacent capability that you can triangulate the required skill from what you already know, under pressure, when the stakes are real. You aren’t learning from scratch; you are mapping old patterns onto new territory.

The Evidence: Pattern First, Vocabulary Second Leading and kerning for book publishing? I didn’t know those terms. I didn’t know what “visual hierarchy” or “vertical rhythm” were called in typography. But I knew the physics of them from map design. I knew that if labels were too dense, the user got confused. I mapped that spatial instinct from the map to the page. I learned the proper terms years later, but I used the mapping immediately.

CMYK color separation? I didn’t know print theory. But I understood how to isolate signal bands in satellite imagery. To me, the “four-color process” wasn’t a new concept I had to memorize; it was just four specific signal bands I had to isolate. I treated the ink like data layers.

H.264 codecs and Rec. 709 color space? I didn’t go to film school. I didn’t know the language of “chroma subsampling.” But I understood pipe capacity and compression algorithms from server bandwidth management. I didn’t need to be a colorist; I just needed to treat pixels like packets moving through a constricted pipe.

This is why the scalpel pattern works operationally but creates evaluation friction.

Traditional credentialing asks: “Do you know the vocabulary of parkour?” The answer is: “No.” The integrated operator answers: “I don’t know the words, but I know the physics. I know running and gymnastics, and I can synthesize the mechanics of parkour from those domains to cross this gap right now.”

That answer doesn’t fit the form. But it builds the bridge.

The integrated operator isn’t someone who already knows everything. It’s someone who can synthesize what’s needed from adjacent domains (often before they even know the proper names for what they are doing), and deliver the result.

The Trade-offs: Scalpel and Swiss Army Knife Are Both Essential

Here’s the honest assessment without making this sound like damage or pretense:

The Swiss Army Knife (Federation):

- Meets participants where they are

- Accepts variety and different capability levels

- Bears the cost of coordination and translation

- Scales gracefully as you add capacity

- Resilient through distributed ownership

- Right tool for steady-state operations with established protocols

The Scalpel (Integration):

- Exactly the right tool for exactly the right job

- Maximum velocity and precision for novel work

- Requires complete end-to-end capability in the operator

- Doesn’t scale beyond operator capacity

- Can be harmful to the operator if overused

- Fragile if misused even slightly: trades sharpness for durability

Neither is superior. They’re different tools for different contexts.

And critically: you can’t use the scalpel unless you actually have the integrated skillset. Most people are forced into federation not by choice but by capability gaps. I can choose integration for certain work because I have the cross-domain skills to execute it. That’s not bragging, it’s explaining why the architecture is even viable.

The Stewardship of the Pattern

I struggle to write this. The imposter syndrome is strong in this one. Documenting this pattern feels arrogant: “here’s why I can do things others can’t” sounds pretentious even when it’s operationally true. But I realize there are other people who will come after me who operate this way and don’t have a framework for understanding it or articulating it.

If I can provide an example so they don’t have to reinvent the wheel, if I can pass down the tacit knowledge of “this is what’s going on for you, this is why you’re able to insert into these federated environments and pull something off in days that would take a committee half a year, here’s how you document it, here’s how you talk about it”… then the discomfort is worth it.

Because here’s the truth that sounds arrogant but isn’t: no one will understand this pattern except people who operate this way. Traditional evaluation frameworks don’t capture it. Panel interviews can’t assess it. Credentials don’t certify it. So either you document it through work product and provide the framework for others to do the same, or the capability stays invisible and everyone who has it thinks they’re an imposter.

What’s worse: keeping it in my head because I’m scared of what people might think, or putting it out there so it can help someone who needs the example?

The documentation is stewardship. Not ego.

Decision Framework: When to Choose Each Architecture

Operate integrated when:

- You’re solo or working with a small team of sidecar specialists with clear boundaries.

- The work is novel and doesn’t fit established playbooks.

- Velocity is critical and handoff friction would kill the timeline.

- You personally have the complete skillset required.

- The deliverable is bounded and doesn’t require ongoing multi-stakeholder operation.

Operate federated when:

- Multiple stakeholders with distributed authority are involved.

- The work is steady-state with established protocols.

- Scalability matters more than velocity.

- Training pipelines and task books exist.

- Sovereignty is distributed and must be respected.

- Long-term operation requires capacity beyond one person.

Context-switch between architectures when:

- Mission requirements change mid-stream.

- You’re operating in crisis environments where both modes are needed.

- Novel requirements appear inside established federated systems.

- You need surgical precision inside a larger coordinated effort.

The Katrina team demonstrated this constantly. We operated integrated for specific high-velocity novel builds, then plugged back into federated coordination for the larger mission architecture.

Refining the Doctrine

This refines Doctrine 01: Federation vs Integration in Mission Networks with a critical insight:

Integration brittleness is multi-actor dependency, not integration itself.

A solo integrated operator with complete end-to-end capability is actually highly resilient. No handoff failures. No coordination overhead. No dependency on others’ timelines. The brittleness only appears when you introduce distributed authority and multiple actors who must coordinate.

This doesn’t invalidate the original doctrine. Federation is still the right default for organizational systems serving multiple stakeholders. But it adds necessary nuance:

For solo operators or small teams with integrated capability, working on novel bounded deliverables where velocity matters, integration is the high-performance architecture.

The scalpel isn’t better than the Swiss Army knife. But when you need surgery, and you have a surgeon, use the scalpel.

This field note connects to:

- Sphere and Spikes: Building What You Need Without Becoming a Specialist (explains how integrated skillset develops)

Last Updated on January 17, 2026