When Data And Applications Divorce: Separating The Two Without Tearing The System Apart

In architecture circles, “decouple data from the application” often gets repeated like a spell.

Say it enough times and you start to believe that separating data from applications is always good and never painful. In real systems, it is more complicated. Separation can unlock federation, resilience and swappability. It can also introduce new failure modes and complexity if you do it without a clear reason.

I have lived on both sides of that line.

On the iCAV side, where we had to federate critical infrastructure data from many partners and keep it usable over time.

On the wildland fire side, where tight integration in a narrow domain sometimes justified keeping data and logic very close together.

The point of this doctrine is simple.

Do not separate data and applications because it sounds modern. Do it when the system you are building actually demands it.

When Data Is The Asset And Apps Are Just Lenses

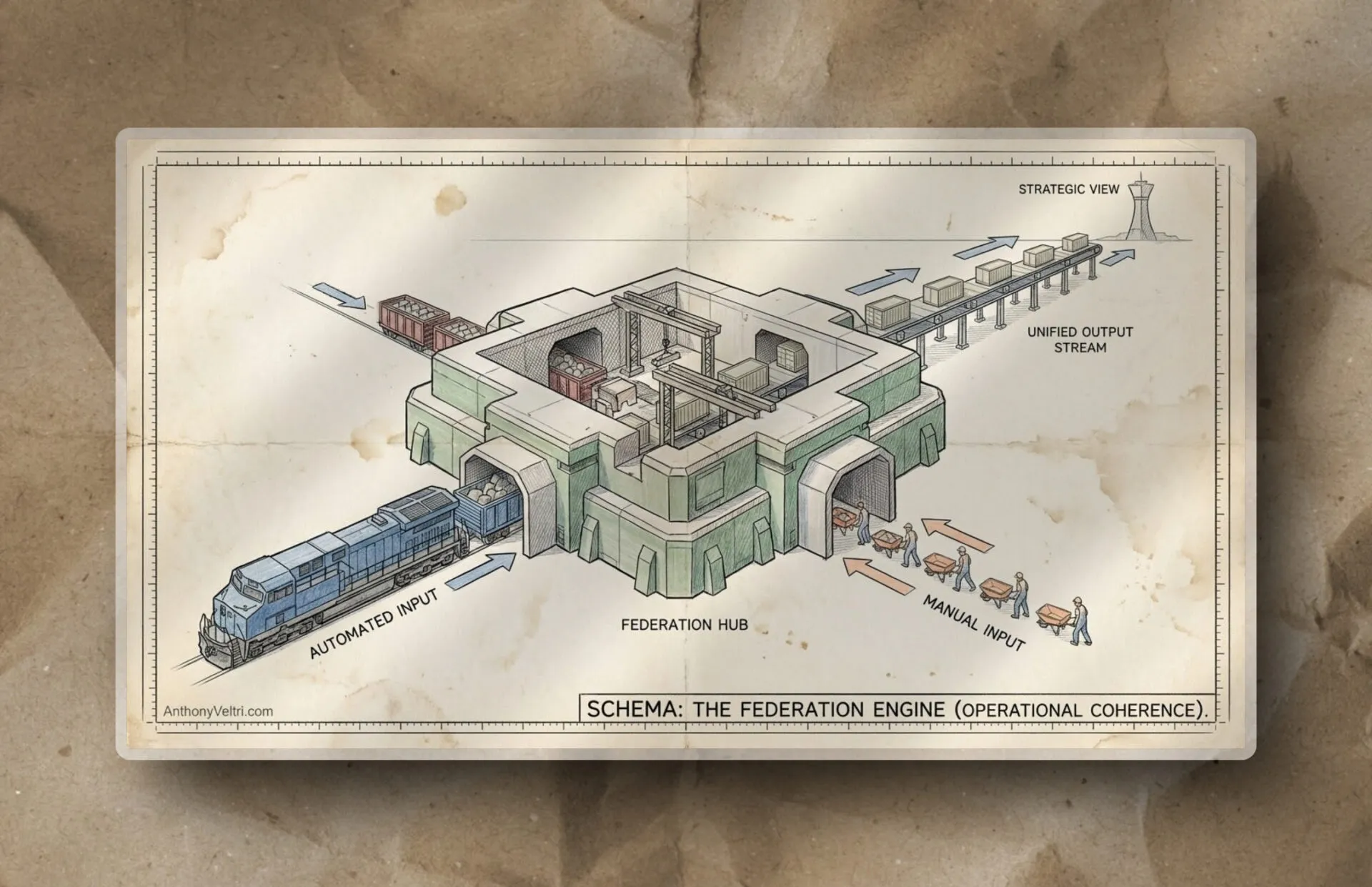

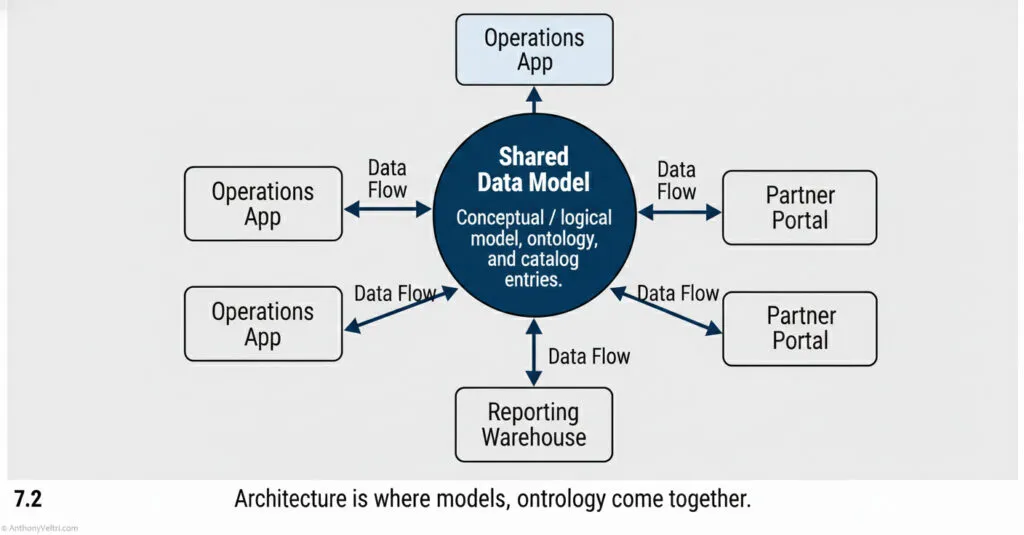

Architecture as Service: By providing a standard “Hub” and “Connector” pattern, we allowed partners to plug in at their own speed, rather than rebuilding the pipe every time. Golden Datasets and The Golden Hub. In a federated system, you cannot centralize everything. Instead, you create a “Shared Data Model” (Blue Center) that acts as the Golden View, while partner systems (Grey Boxes) retain their local data.

In iCAV, the data was the main character.

The platform pulled information about the 19 critical infrastructure and key resource sectors of the time. Finance, transportation, power generation and more. The providers included federal agencies, tribal nations and local municipalities. Each had different systems, habits and levels of maturity.

The applications were lenses.

- A viewer for decision makers in a command center

- Analytics tools for planners and analysts

- Reporting outputs for senior leadership

- Interfaces for partners who wanted to push and pull information

If we had bound the data tightly to one of those applications, the system would have become hostage to that one tool. Every new viewer or analysis job would have required invasive surgery. Every time a partner wanted to consume the data in a different way, we would have had to duplicate logic and storage.

So we chose to separate.

We treated the data services and models as their own product and treated applications as clients of that product. The separation was not perfect, and it evolved over time, but the intent was clear.

That gave us several advantages.

- Many consumers, one spine. Multiple tools could read from the same underlying structure without forcing each other’s release cycles.

- Longevity of the data. We knew the data about infrastructure and incidents would outlive any particular viewer or user interface.

- Room for sovereignty. Partners could keep their systems, expose agreed slices of data at interfaces and still contribute to a shared picture.

- Focused security work. We could treat the interfaces as the primary security surface instead of trying to harden every consumer and producer equally.

In that kind of environment, coupling data to any one application is a long term liability. The data becomes trapped inside someone’s model of the world. Your only choices are to rewrite that app, or to build an ever growing ring of fragile integrations around it.

What Happens When Apps Own The Data

Most organizations start with applications owning the data because it is the easiest way to begin.

You buy or build a tool. It comes with its own schema and storage. You add some workflows. You point users at it. On day one, nothing seems wrong.

The trouble shows up later.

- You want to add a second tool that needs the same data. You now have to synchronize two copies or write a fragile bridge.

- Two departments buy different tools that both contain overlapping slices of the same reality. Neither is authoritative. Reports disagree.

- You want to expose data to external partners without giving them access to the entire application. Suddenly you are hand crafting extracts and manual feeds.

You slowly grow a “Frankenstein” architecture.

Pieces of reality are scattered across many applications. Nobody trusts any single view. Humans become the interface as analysts and project leads reconcile and reformat information over and over.

At that point someone says “we need a data centric architecture.”

They are not wrong.

They are also late.

The real doctrine question is not whether data centricity is good. It is when the system is ripe for it, and whether you are ready to treat data as a first class product, not just as exhaust from applications.

When Separation Is Exactly The Right Move

Separating data from applications is not a fashion statement. It is a response to specific conditions.

It is the right move when at least some of the following are true.

- The data will outlive any one application.

Critical infrastructure, fire history, patient records, alliance level tasking. If you know the information will matter beyond the lifetime of a single tool, you should not bury it inside that tool. - There are or will be multiple consumers.

If you already have more than one viewer, report, or analytics pipeline relying on the same facts, you are asking for trouble with app owned data. - Sovereignty and federation are real.

When you work with partners who cannot or will not adopt your application, but who are willing to exchange data, separation is what lets you respect their sovereignty while still building a coherent picture. - You need a golden source, not five conflicting ones.

If leadership is arguing about which report is right, not about what to do, you have a data product problem. Separation lets you put clarity at the spine instead of at the edges. - You anticipate tool churn.

In long lived programs, applications come and go. If you have separated data correctly, you can retire or replace a tool without losing your history or tearing apart the rest of the system.

Under those conditions, holding onto application owned data is like anchoring your house to a parked car. It feels stable at first. It ends badly as soon as anything needs to move.

When Keeping Data Close To The App Still Makes Sense

The flip side is just as important. There are domains where aggressive separation is premature or actively harmful.

Some examples.

- Small, focused tools with one clear consumer.

A single purpose application used by one team, with no realistic need for external consumption, may not benefit from a separate data layer. The extra hops add operational risk without enough payoff. - Embedded and real time systems.

In systems where timing is measured in microseconds and resources are constrained, you often keep data and logic together by design. The “database” may be a carefully structured memory region. Splitting that into a separate service would break the core constraints. - Exploratory products where the domain is not stable.

If you are still discovering what the product is and the data model changes weekly, a heavy, centralized data platform can slow you down. You might prototype with tight coupling and extract a data product later once patterns stabilize. - Domains where version alignment is life critical.

There are cases where the code that uses the data must track the data version so closely that separation adds risk. You have to be very deliberate here, but blindly inserting a shared data layer can create hidden incompatibilities.

The test is not “do we like microservices” or “do we want to say data lake in a slide deck.”

The test is:

- Will this separation make the system more honest, more resilient and easier to reason about

- Or will it simply create new places for things to break while everyone still behaves as if the applications own the truth

NWCG And The Places Where Tight Coupling Is Worth The Cost

In the wildland fire community, data and applications are not always neatly separated either.

Some parts are moving in that direction, especially where incident records and resource ordering need to be consumed by many tools and agencies. Systems like IRWIN function as shared sources of truth in that sense.

In other parts, the tight coupling between role, tool and data is intentional.

When a dispatcher uses a specific local console, or an air attack supervisor uses a particular pattern for logging events during a drop run, you are dealing with a small, tightly scoped interaction between a human and a tool, under time pressure. The point is not to make that data universally consumable in the moment. The point is to keep aircraft and crews alive.

Later, some of that data will be abstracted into shared systems, reviewed and standardized. In the heat of an operational period, you accept local coupling because the cost of abstraction would be paid in attention and seconds, not in budget.

In other words, the wildland fire community uses both patterns.

- Data centric approaches when they need shared history, cross incident analysis and multi agency visibility.

- Tight coupling when the unit of work is a human plus a tool plus a very specific task, where abstraction would only add latency.

The doctrine is not “always separate.”

It is “separate where the lifespan and sharing requirements demand it, and keep things close where local performance and safety do.”

Doctrine: Choosing Where The Real Spine Lives

If I had to compress this into a simple rule for myself, it would be this.

- Put your spine where your system most needs truth to persist.

If your system lives or dies on shared situational awareness, put the spine in shared data.

If your system lives or dies on the real time performance of a single crew with a single tool, put the spine in that interaction and integrate it later.

In practice, that means asking a few hard questions early.

- What parts of our information must stay coherent across tools, agencies and time

- Which consumers and producers are we willing to break if we change a given schema or interface

- Where are we secretly using humans as glue between applications that should be clients of a common data product

If you find that the same reality is being re entered, re reconciled and re argued across many applications, you already have your answer. The data wants a life of its own. Your job as an architect is to give it one.

If, on the other hand, you find a small, high focus domain where splitting logic from data would mostly add bureaucracy and points of failure, you can allow yourself to keep them together for now. The key is that you make that choice consciously, and you revisit it whenever the context changes.

You cannot integrate your way out of sovereignty. You also cannot federate your way out of every local responsibility. Separating data from applications is not about winning a design argument. It is about putting stability, truth and ownership where your system actually needs them.

Last Updated on December 7, 2025