When You Choose Integration over Federation On Purpose

Federation is my default. Integration is my exception.

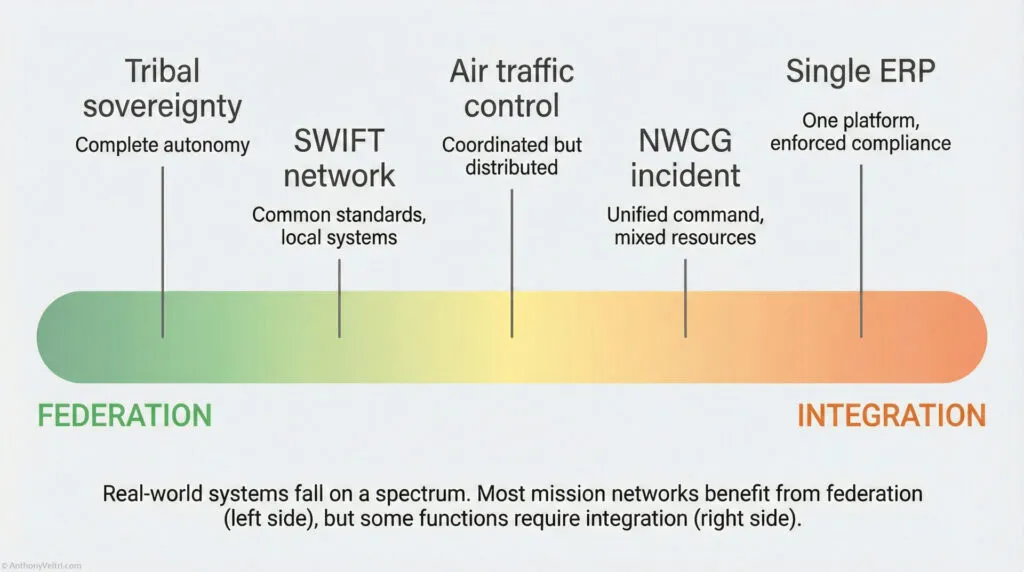

The fire system sits in the middle of the spectrum: “Coordinated but Distributed” just like Air Traffic Control. It balances local sovereignty with national power.

The Lesson: Successful systems are often integrated locally (for control) but federated globally (for scale). Respecting Sovereignty: In a disaster, you cannot force Integration (Right). You must accept Federation (Left) because local sovereignty is a constraint you cannot wish away.

The clearest example of that exception is the wildland fire community in the United States, particularly through the National Wildfire Coordinating Group. NWCG brings together the Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, National Park Service and other partners.

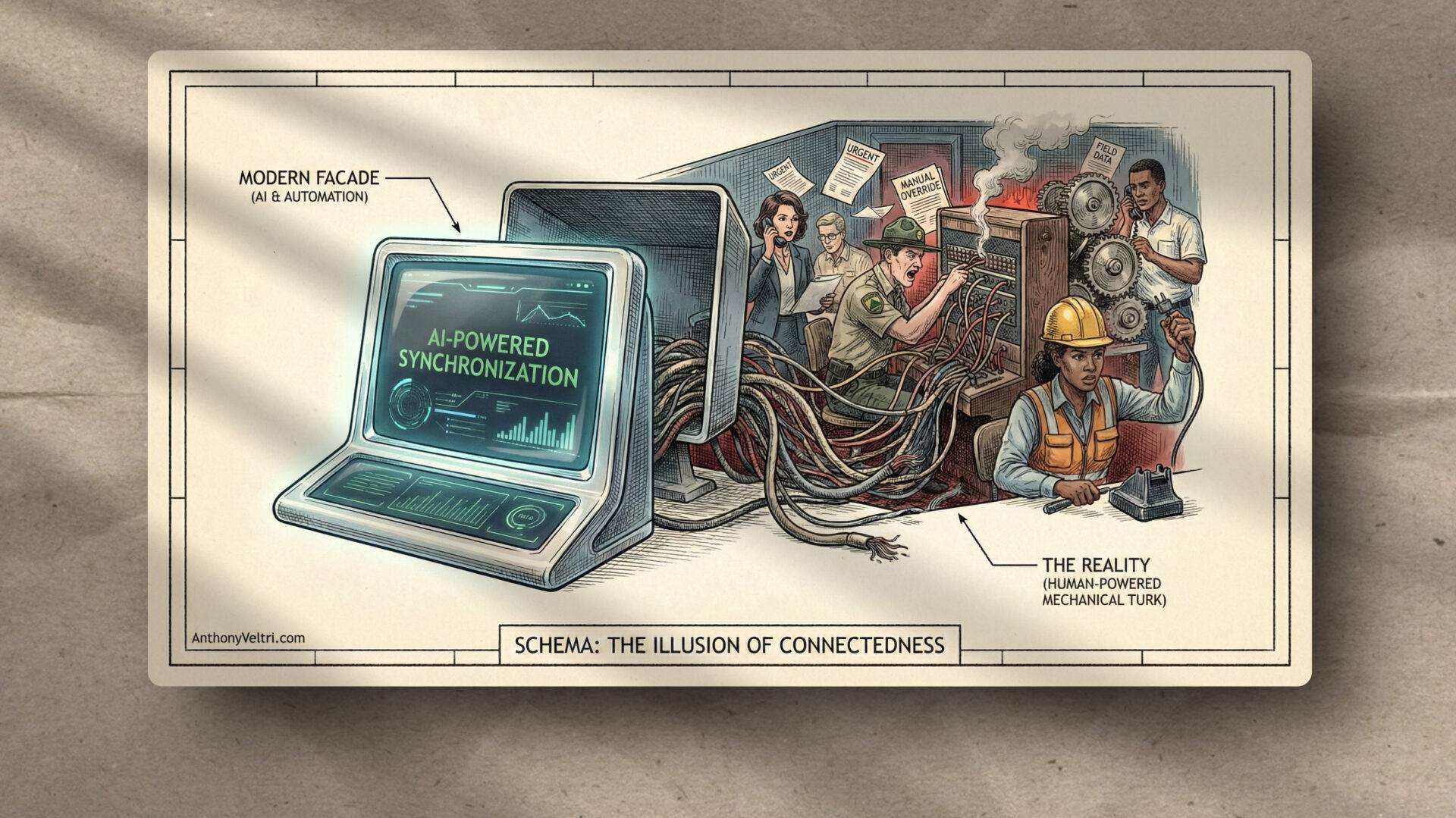

Outside of wildfire, these agencies are quite federated. Their records systems are different. Their workflows and tempos are different. You could not simply drop a records clerk from one agency into another and expect immediate productivity. They would understand the policies, but the systems would feel foreign.

Wildland fire is different.

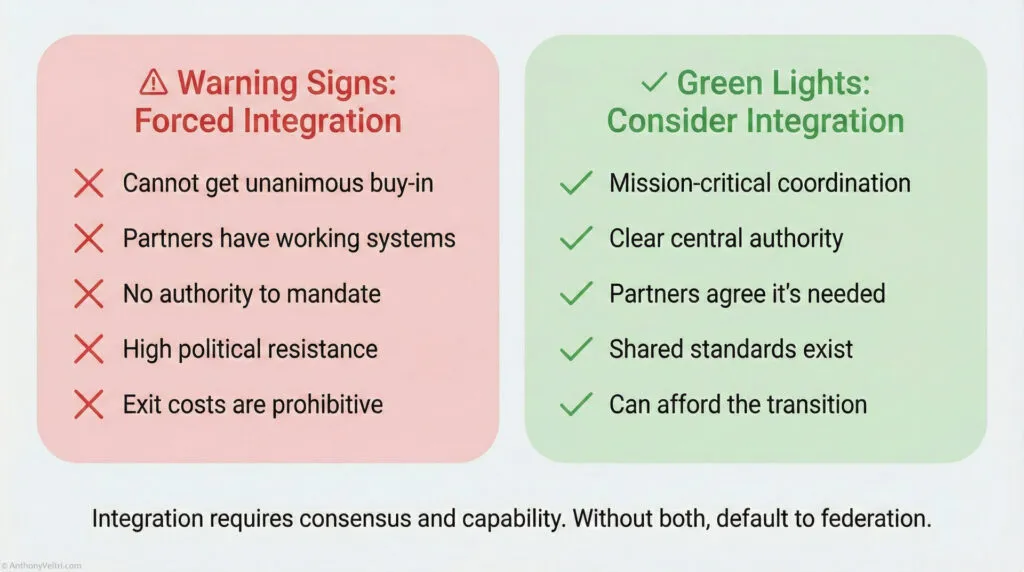

The Green Light: You only integrate when you have “Mission Critical Coordination” and “Clear Central Authority.” Wildland Fire checks every box in the Green column. Most enterprise projects do not.

When a fire complex spins up, lives and aviation safety are on the line. There is no time for “my flavor” of data or “your flavor” of workflow. The community recognized that and did something rare in the federal space: they voluntarily forced compliance with shared standards in a narrow domain.

You can see it in systems like IRWIN, which tracks incident records, and in ROSS, the Resource Ordering System. You can see it in the way drone and thermal imaging data are handled during fires.

At one point, LIDAR became more widely available. Multiple parts of the same agency were flying overlapping LIDAR sets over the same ground: a region office, a ranger district, a national program with grant funding. They were not talking to each other. That duplication still happens in their “home” business.

On a fire, they behave differently.

They align:

- File naming conventions.

- Data formats and schemas.

- Reporting cadence.

- Contracting and resource ordering rules.

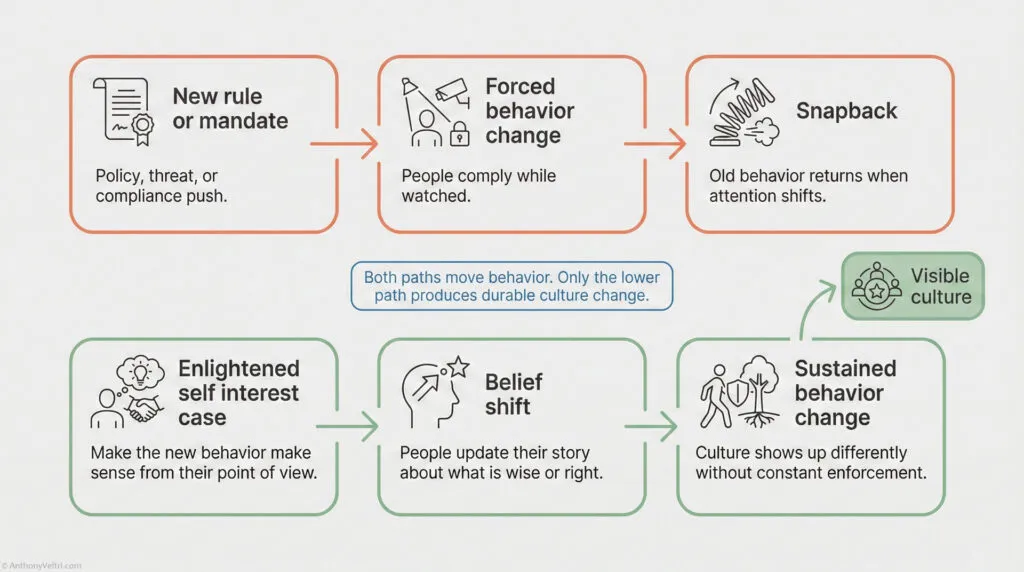

Someone from BLM can slot into a fire role that someone from the Forest Service held last week and work inside the same structures. Not because they gave up their agency identity, but because everyone agrees that, in this narrow context, the mission matters more than local variation.

In my career, I have been on both sides of that integration work. Early on I consumed the standards downstream, building systems that needed to ingest and use that data reliably. Later, as I advanced, I was asked to facilitate the teams that defined some of those standards. I was not the person writing each line of the technical specification. My job was to get the right experts in the room, frame the tradeoffs, and guide them toward agreement that they could all live with in the heat of a fire season.

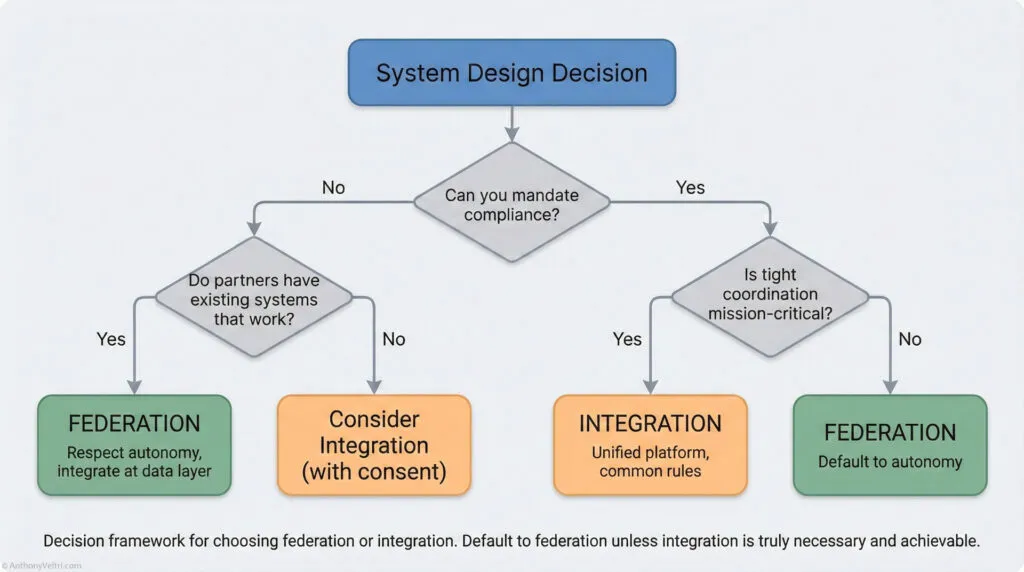

From that experience, my integration doctrine is straightforward:

- You do not try to integrate everything.

- You integrate only where the mission is narrow, time critical, and life safety or strategic risk justify the cost of strict compliance.

- Everywhere else, you go back to federation.

From wildfire coordination at the local level to an alliance like NATO operating at the multi-theater level, that translates into a very practical pattern:

- Default to federated, data-centric approaches that respect national sovereignty and uneven maturity.

- Identify a small number of mission domains where tighter integration and common standards will save lives or prevent major strategic failure.

- Focus your integration energy there, and accept the cost of compliance as a conscious choice, not an accidental byproduct.

Having worked on both iCAV and NWCG-related systems, I am comfortable navigating that spectrum. The real craft is not choosing federation or integration in the abstract. It is knowing when the situation has shifted enough that you should intentionally move from one to the other.

Last Updated on December 7, 2025