Why This Site Has Four Navigation Systems

In parochial school, we were supposed to carry a notepad and record our assignments. If you were inspected without it, you received a demerit. I never kept the notepad.

I forgot one assignment in seven years.

I remember it because it was so rare. Seventh grade science fair. We drew numbers 1-30 for presentation order. I was convinced I was number 15, third day. I prepared my project – filtering cigarette smoke through various materials to show residue retention in a various materials (approximating lung tissue). When my teacher called my name on day two, position 10, I was shocked.

I wasn’t ready. I knew the material, but I was unnerved. My teacher, a Vietnam Vet, was not. I struggled to light the cigarette for the demonstration. My teacher – strict, no-nonsense, one of the best science teachers I ever had – took the cigarette, lit it, took a few drags to get it going (unimaginable today), and handed it back. He wasn’t a smoker. But he wanted to see me succeed, and he knew that meant I had to go in my assigned spot, even though i was visibly shaken.

He broke my OODA loop, then helped me recover it. I gave a great presentation.

I still remember his assigned number. Day two, position 10. Not because I wrote it down, but because the pattern broke.

That’s how pattern-matching works. The exceptions are more memorable than the rules.

When Measurement Systems Optimize for What’s Easy to Grade

The notepad was someone else’s memory system. Pattern-matching is mine.

But here’s the thing: the notepad is easier to check and grade for inputs. You either have the assignment written down or you don’t. Binary. Measurable. Auditable.

This creates a tempting assumption: if you control the inputs perfectly, you’ll get predictable outputs. If everyone uses the notepad correctly, everyone will remember their assignments.

Except we know that’s not how the world works.

I’ve seen this pattern in professional certifications that test taxonomy memorization rather than operational capability. You can pass an exam by selecting the stage-correct activity from a list of “true statements” – all options are plausible, but only one is the canonical move for that framework stage.

That’s kata. It’s vocabulary fluency. It’s knowing which words match which boxes.

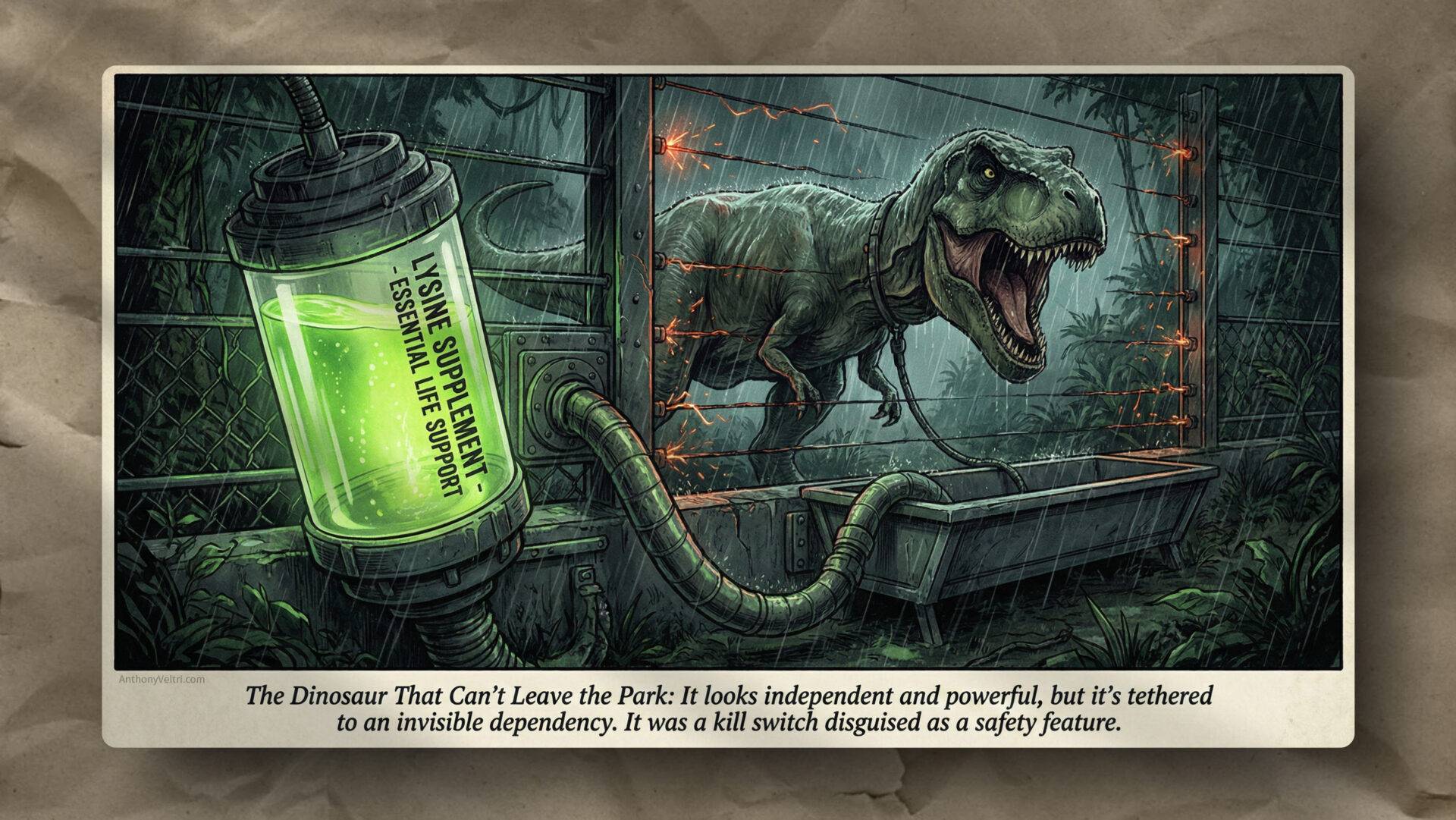

What it’s not: evidence that you can perform under contact with reality, where the other side has agency, changes incentives, routes around you, or disagrees on what “value” even means.

The measurement system optimizes for what’s easy to grade (did you pick the right option from the list?) rather than what actually matters (can you deliver outcomes when reality resists?).

This is the same failure mode as the notepad: you can have perfect compliance (everyone writes in their notebook, everyone passes the certification exam) while completely missing the question of whether people can actually perform when the schema breaks.

When my science fair schema broke (forgot the number, visible disorientation, couldn’t light the cigarette), the notepad wouldn’t have helped me recover. The teacher did – by switching to a different mechanism. He didn’t ask me to check my notes. He lit the cigarette and got the experiment running.

Recovery required a different schema, not better compliance with the original one.

What Schemas Actually Are

Before I explain pattern-matching, I need to explain schemas.

A schema is a mental framework – a template you use to organize information and filter what’s meaningful from what’s noise.

Restaurant schema:

- I arrive

- I get seated

- I order

- I eat

- I pay

- I leave

Once you have that template, there’s less cognitive load required. You know the sequence. You know what questions to ask. You know what constitutes normal versus exceptional.

The first time you flew in an airport, everything was overwhelming because you hadn’t developed the schema yet. Four or five trips later, you had the template. Now airports are routine.

Schemas tell you what to pay attention to, what to ignore, and what actions make sense in what sequence.

Pattern-Matching Is Schema-Stacking

I don’t store information sequentially. I cross-reference by mechanism.

Session hijacking in 1999 sits next to zero trust architecture, disaster response staging, and jiu-jitsu guard retention – not because they’re related topics, but because they share a structural pattern: trust boundaries fail when context doesn’t survive disconnection.

This works because I’ve built schemas across multiple domains:

- Bouldering rehearsal

- Jiu-jitsu drilling

- Disaster response

- Systems architecture

- Wildland fire operations

- Federal enterprise systems

- E-commerce platform development

Each is a schema – a mental template that filters for what’s meaningful in that domain.

When I encounter a problem, these schemas activate simultaneously. They’re running parallel pattern recognition, looking for structural matches across domains.

It’s not that I’m connecting unrelated topics. It’s that the same schema recognizes the same pattern across all of them.

This is why it looks like I arrive at answers instantly. I don’t. Multiple schemas are converging on the same pattern in parallel. The synthesis happens fast because four or more filters are running at once. The explanation takes longer because I have to reverse-engineer which schema activated first and articulate the logic linearly.

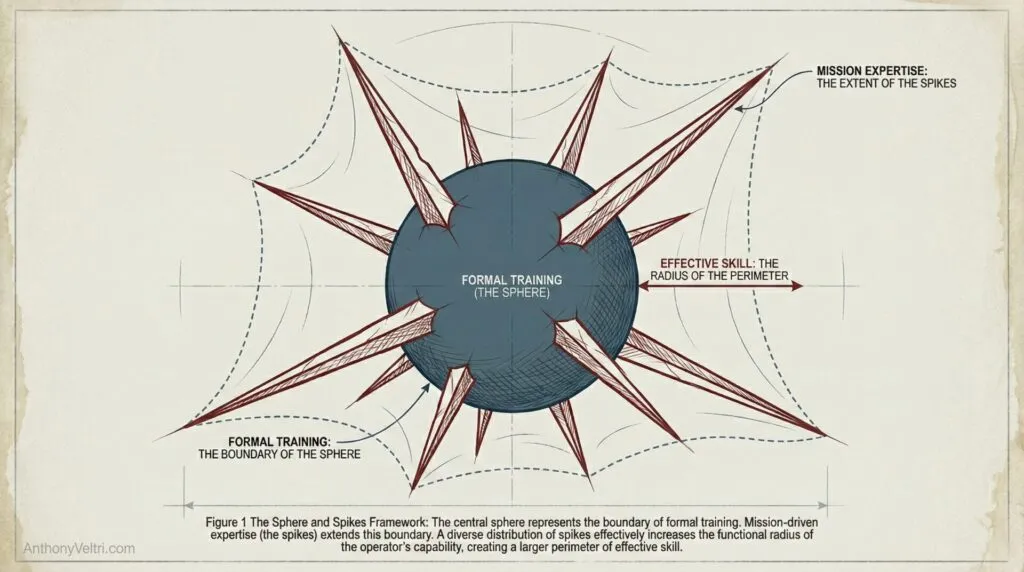

Sphere and Spikes: How Adjacent Schemas Fill Gaps

I don’t have deep schemas for everything. Nobody does.

The “sphere and spikes” framework describes this: maintain general baseline competence (the sphere) while developing targeted deep expertise (the spikes) driven by specific mission requirements.

But here’s what makes schema-stacking powerful: when you have adjacent, somewhat related schemas, you can fill in the pieces.

Restaurant schema + airport schema = train station schema (arrival, ticketing, waiting area, boarding, departure)

Bouldering rehearsal schema + jiu-jitsu drilling schema = systems documentation schema (isolate the move, practice the sequence, test under resistance, integrate with other moves)

You don’t need a perfect schema for every situation. You need enough overlapping schemas that you can synthesize a working framework when you encounter something new.

That’s how pattern-matching extends beyond memorized scenarios. It’s not recall. It’s synthesis from adjacent templates.

The Blessing and the Curse

The blessing: I see connections others miss. Solutions from one domain apply to another. I build reusable frameworks because the same patterns appear everywhere.

The curse: I arrive at conclusions backwards, and that’s socially awkward.

When someone asks “how did you know that?” I have to reverse-engineer the explanation. The synthesis happened via parallel schema activation. The articulation requires linear presentation of one schema at a time.

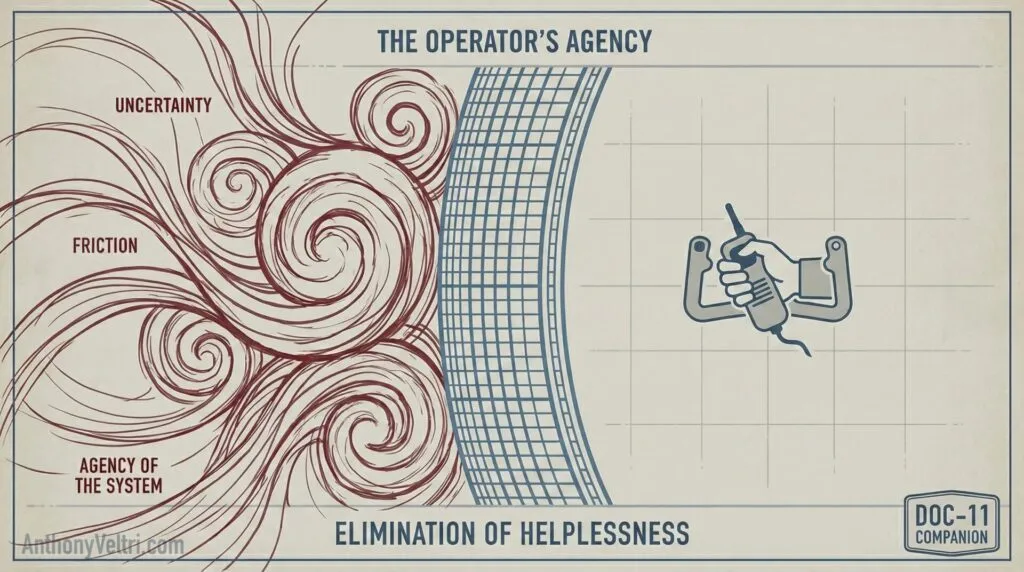

In operational environments, people help you recover when the schema breaks (like my science teacher lighting the cigarette). In evaluation environments, they just watch you struggle and score the disruption.

Operationally superior. Evaluatively opaque.

This is the same problem as certification exams that test taxonomy rather than contact with reality. They measure your ability to select the stage-correct option from a multiple-choice list. They don’t measure your ability to perform when the other side has agency, when incentives change, when reality resists the canonical move.

Pattern-matching works brilliantly when you have time and support to recover from schema breaks. It struggles in artificial evaluation settings that optimize for what’s easy to grade rather than what actually matters.

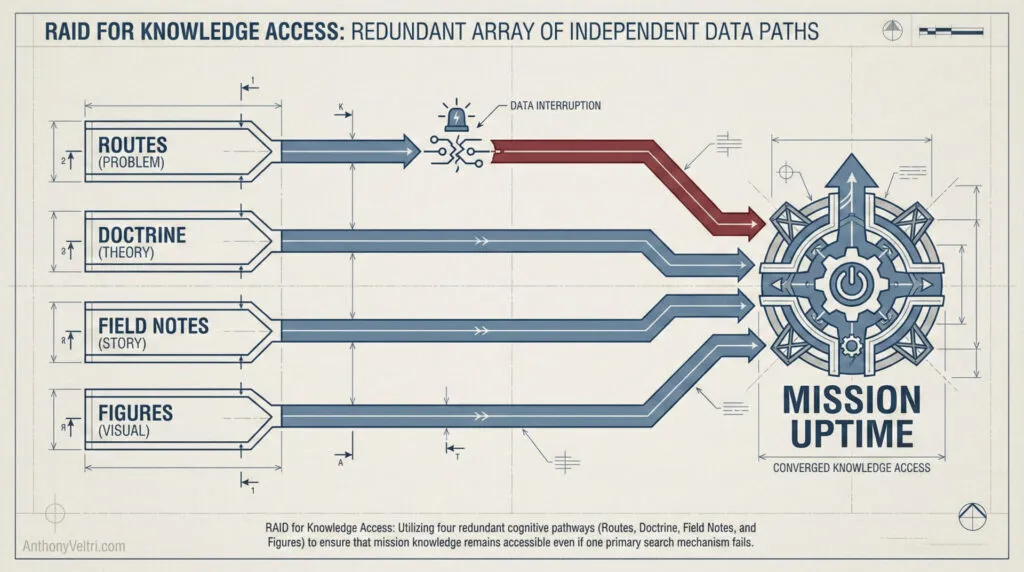

The Four Navigation Systems

This site is the first time I’ve tried to map how this actually works.

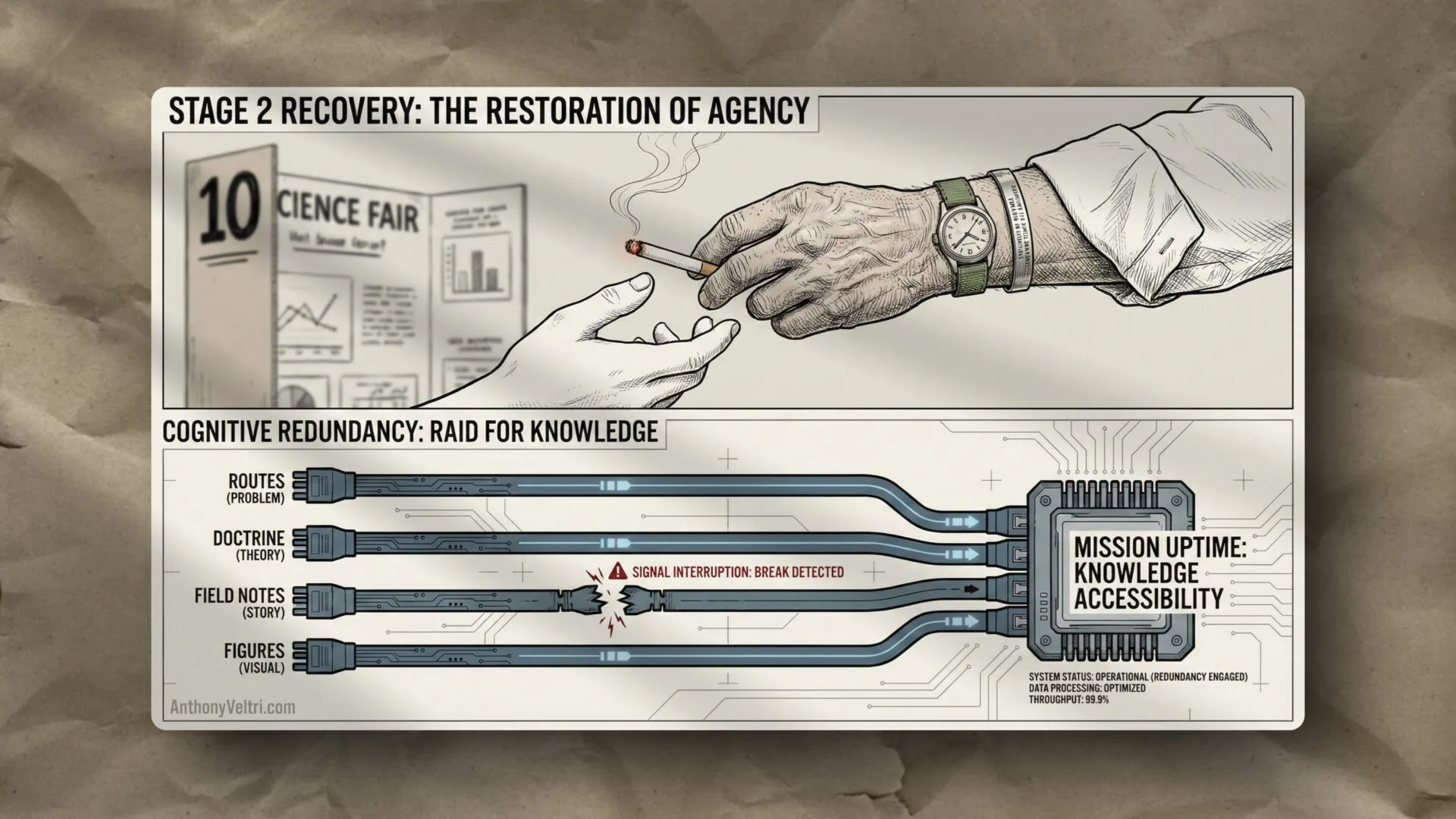

The four navigation systems (Routes, Doctrine Library, Field Notes, Figure Library) aren’t overkill. They’re four different schemas for accessing the same knowledge.

Routes: Problem-based schema. “I have this pain point” → triage → framework

Doctrine Library: Theory-based schema. “I want the systematic framework” → principles → application

Field Notes: Story-based schema. “Show me real examples” → narrative → pattern recognition

Figure Library: Visual-based schema. “I recognize this pattern” → diagram → explanation

Same destination. Four cognitive mechanisms.

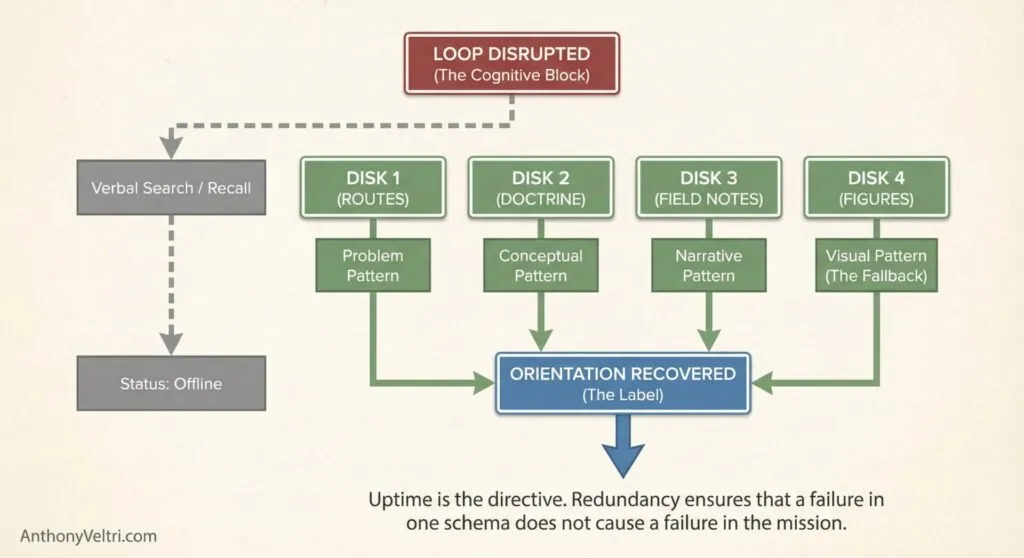

This isn’t like RAID storage with ten hard drives holding the same data for redundancy. (For the systems people: this is RAID for knowledge access. The directive is uptime, not backup. One cognitive path fails, knowledge stays accessible through diverse mechanisms.)

When verbal search breaks, visual recognition might work. When you can’t articulate the problem, you might see it in a story. When theory feels abstract, you might understand it through a scenario.

If one schema fails, three others still work.

The Figure Library: RAID for Knowledge Access

This gallery is the fourth navigation system on this site. It is designed for when your primary search schema fails.

In high-stakes technical or operational environments, your OODA Loop (Observe, Orient, Decide, Act) is your most vital asset. However, under contact with reality, that loop is frequently disrupted. If your only “schema” for finding information is verbal search or sequential recall, a single disruption can stop your momentum entirely.

Why Cognitive Redundancy Matters

Think of this system as RAID for Knowledge. In systems architecture, RAID (Redundant Array of Independent Disks) ensures that if one hard drive fails, the system stays online because the data is mirrored elsewhere.

I have applied that same structural logic to this library:

- Verbal Failure: You cannot remember the exact term like “Interface Void” or “Decision Drag”.

- Narrative Block: You cannot recall the specific story or “Field Note” that contained the solution.

- Conceptual Fatigue: The theoretical “Doctrine” feels too abstract for the immediate crisis.

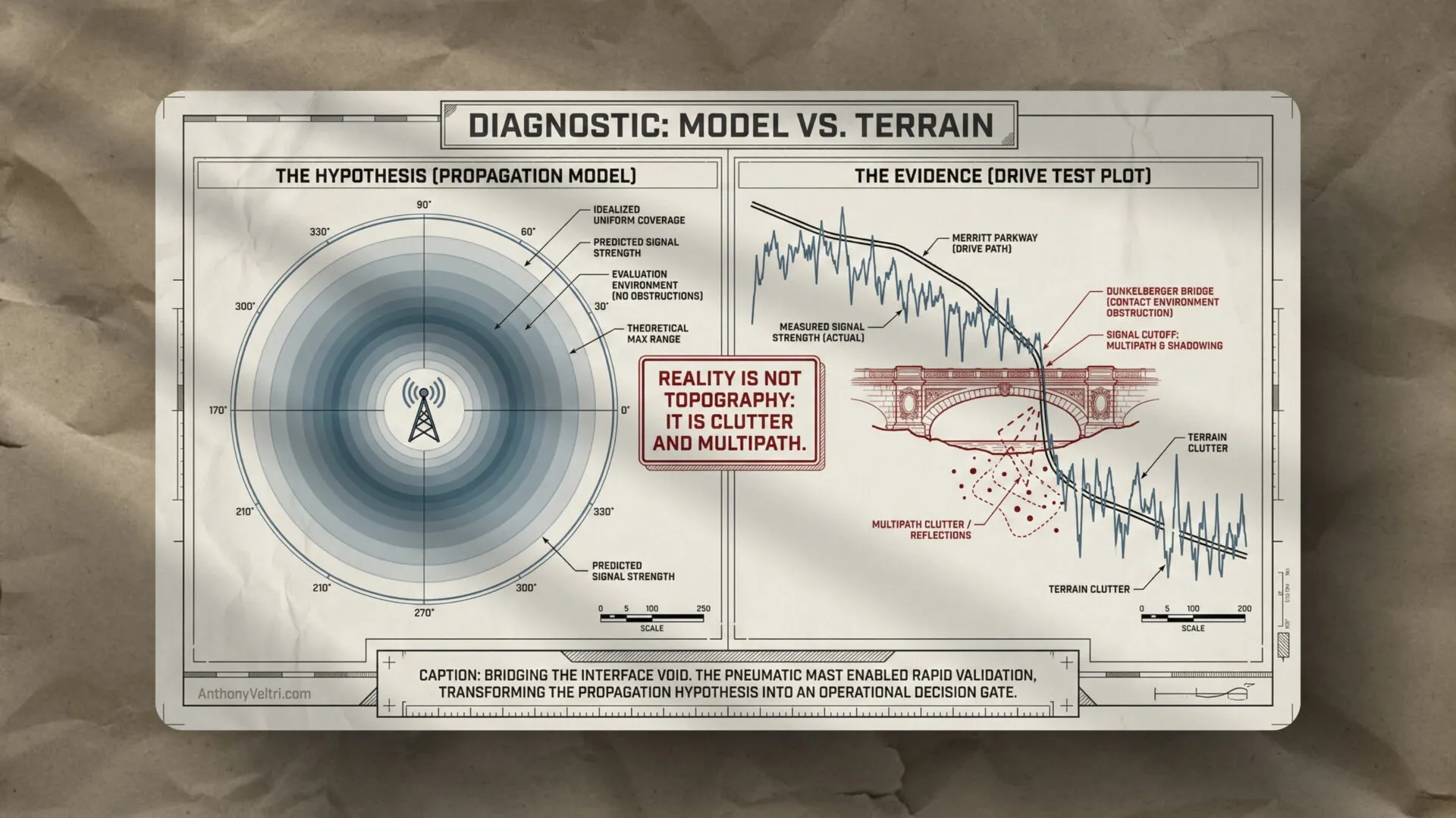

The Figure Library provides the fallback. If one cognitive “disk” is tired or blocked, the information is still mirrored here on a visual disk. Visual pattern recognition uses a different neural pathway than verbal recall. You scan the figures, your brain recognizes a structural pattern (the orange/blue lanes of a degraded system, the stacked boxes of a diagnostic flowchart), and you recover your orientation instantly.

Patterns are Shortcuts to Labels

The goal of this library isn’t just to show you pictures. It is to help you find the Label.

Once you identify the figure, you identify the label (“Interfaces break at seams,” “Heroics create brittleness”). That label gives you immediate control over the problem. It allows you to search for the specific triage steps and communicate the issue to your team without the “social awkwardness” of reverse-engineering your logic under pressure.

Use the Figure Library when the search bar fails you. Visual recognition is the leverage that recovers the loop.

How This Actually Helps: A Concrete Example

Let me show you how someone might use these four systems to find the same piece of knowledge:

Scenario: You saw a diagram about “lanes” somewhere on this site, but you can’t remember where.

Path 1 – Search (fails):

You try searching for “contingency lane” but can’t remember the exact term. No results.

Path 2 – Routes (might work):

You browse Routes looking for “system requires heroics.” That might connect you if you remember the problem context, but maybe you don’t associate “lanes” with heroics.

Path 3 – Figures (works):

You visually scan the Figure Library for an orange/blue lane diagram. Visual recognition activates – different neural pathway than verbal recall. You find “The Lanes: Top Capacity to Load” diagram, click through to Doctrine 10.

Path 4 – Field Notes (works differently):

You browse disaster response stories. You find “Stranded in Vienna, Responsible in Kyiv” and the story triggers recognition: “Oh yeah, that field note had the lanes diagram.”

Same destination (Doctrine 10: Degraded Operations). Four different schemas activated different cognitive processes.

You didn’t need all four paths. You just needed one that matched how your brain was trying to find it. Visual pattern recognition worked when verbal search didn’t.

This is why the four systems aren’t redundant backups. They’re cognitive diversity.

Someone whose verbal search breaks can still succeed via:

- Visual pattern recognition (Figures)

- Problem pattern recognition (Routes)

- Narrative pattern recognition (Field Notes)

- Conceptual pattern recognition (Doctrine)

Why This Works Even If You Don’t Stack Schemas

You might be thinking: “I don’t pattern-match across four domains simultaneously. Does this still help me?”

Yes. Here’s why.

Patterns are shortcuts to schemas. Schemas are shortcuts to labeling. Labels give you control.

You don’t need to stack multiple schemas like I do. But having access to multiple schemas increases your odds of finding one that works for how you think.

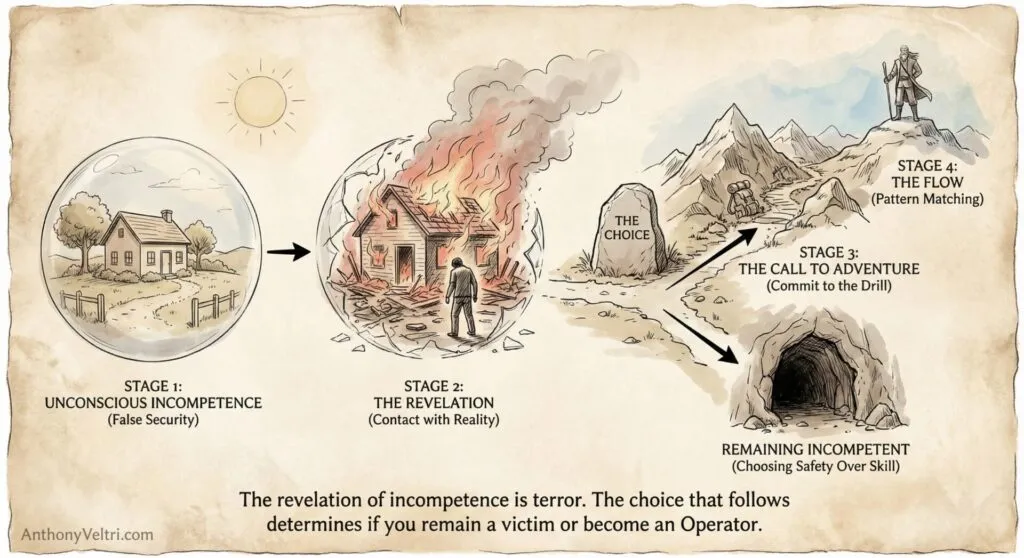

Example: The competency stages framework.

- Unconscious incompetent (you don’t know what you don’t know)

- Conscious incompetent (you know you don’t know)

- Conscious competent (you can do it with effort)

- Unconscious competent (you can do it without thinking)

That’s ONE schema. Learn it, and suddenly you can label where you are in any learning journey. My kids can identify these stages in themselves. The label gives them control.

That framework describes the mechanics of learning. But it treats all learning as equivalent. It doesn’t account for stakes.

Learning to play piano for enjoyment follows those same four stages. So does learning CPR after watching someone collapse and realizing you were powerless to help. Same competency progression. Completely different commitment level.

The four-stage diagram (safety, crisis, choice, growth/stasis) maps what actually happens when stakes reveal themselves. You start in safety (unconscious incompetent – you don’t know CPR exists or matters). Then comes the revelation: someone collapses, you can’t help, you realize the gap. That’s the crisis (conscious incompetent, but with consequences attached).

Now you face a choice. You can learn CPR (move toward conscious competent) or you can avoid situations where it matters (stay frozen at conscious incompetent). The diagram shows what the competency stages don’t: there’s a decision point where stakes determine whether you progress or retreat.

Piano lessons have low stakes. Miss a practice session? No consequences beyond slower progress. Learning CPR after contact with reality? The stakes are visible. Someone might die because you froze.

Same learning mechanics. Different motivation. Different commitment. Different likelihood of reaching unconscious competence.

The competency stages describe the path. The four-stage diagram describes why some people walk it and others don’t.

When you label something, you can talk about it, search for it, solve for it. Without the label, you’re just frustrated that “something isn’t working.”

The four navigation systems provide four different ways to find the label that matches your situation.

You don’t need to use all four. You don’t need to pattern-match like I do. You just need whichever path works for how you’re trying to find it.

- Can’t remember the search term? Try visual recognition (Figures)

- Don’t know the doctrine name? Try problem triage (Routes)

- Can’t articulate the framework? Try story matching (Field Notes)

- Want the systematic theory? Try browsing (Doctrine Library)

One schema – just one useful label – can be enough to give you a shortcut you didn’t have before.

“Interfaces break at seams.” That’s a label. Once you have it, you can recognize that pattern, search for solutions, communicate the problem to others.

“Decisions stall without clear intent.” Another label. Now you can diagnose why meetings go nowhere.

“Heroics create brittleness.” Another shortcut. Now you can identify single points of failure.

You don’t need to discover these patterns yourself through schema-stacking. You can borrow the label and apply it when you recognize the situation. That’s the value of having multiple navigation paths – it increases your odds of finding the shortcut that works for your specific situation.

This Isn’t About Being Special

We all have strengths and deficits. But we have to ask: ‘Compared to what?’

Pattern-matching looks like a deficit in traditional evaluation contexts. I arrive at answers without showing my work. I synthesize across domains in ways that feel unmotivated to people expecting linear reasoning. I struggle to explain how I got there because the schemas fired in parallel, not in sequence.

Compared to checkbox evaluation, that’s a weakness. Compared to operational environments where you need rapid synthesis under pressure? That’s capability.

The problem isn’t the capability. The problem is the measurement system optimizing for what’s easy to grade rather than what actually delivers outcomes.

This is why I built evaluation bypass infrastructure. I’m not trying to make myself look better at checkbox evaluation. I’m documenting work product so people can assess capability directly: ‘Here’s what I built. Here’s how it works. Here’s the doctrine explaining the patterns. Does this solve your problem?’

That’s the comparison that matters. Not ‘Can you perform in our interview panel?’ but ‘Can you deliver this outcome when reality resists?’

I’m explaining what I discovered about how I think, and offering it as a tool if it helps you. Pattern-matching via schema-stacking is my operational mode. The four navigation systems map how that works.

But the real value isn’t the pattern-matching. The real value is the labeling.

Once you have a label (“interfaces break at seams,” “decisions stall without clear intent,” “heroics create brittleness”), you don’t need to pattern-match everything. You just need that one shortcut.

The four navigation systems are different paths to finding the right label for your situation. Use whichever one works. Ignore the others. There’s no requirement to use all four, and there’s no advantage to forcing yourself into a schema that doesn’t match how you think.

The notebook worked for some students. Pattern-matching worked for me. The four navigation systems work for people who think in problems, theories, stories, or visuals.

Pick the tool that fits. Leave the rest.

Last Updated on December 22, 2025