You Remember My Values, But Not Yours

A Forest Service Story About Narrative, Resilience, and Memory

Disclaimer:

This case study is based on volunteer work I did with a U.S. Forest Service region during the Chief’s Operation Care & Recovery effort. I developed this material independently and shared it with that region to support their resilience efforts. All interpretations, conclusions, and lessons here are my own and do not represent official policy or positions of the U.S. Forest Service or USDA.

1. Context: Why I Was in the Room

In 2020, the Pacific Northwest Region (Region 6) of the U.S. Forest Service was getting hammered from multiple directions:

- COVID was burning through staff, families, and communities.

- The Detroit, Oregon fires, Southern Oregon fires, and surrounding complexes wiped out entire towns and landscapes.

- People were exhausted, angry, grieving, and still trying to do their jobs.

The Chief’s Operation Care & Recovery was launched nationally, but Region 6 was feeling the weight in a very specific way. Leadership wanted to talk about resilience, care, and recovery in a way that was real, not just a memo.

I was brought in as a volunteer to help:

- Shape the narrative around resilience.

- Design a podcast concept that would reach both employees and the public.

- Give leaders a way to talk about what had happened without sounding like a press release.

This guide is the pattern I used, and what I learned.

2. The Default Belief: “The Science Will Speak for Itself”

When I work with federal agencies, I hear some version of this belief a lot:

“We have science, we have values, we have a mission.

If people don’t understand us, that’s their problem.”

It sounds noble. It feels objective. It also fails.

So I opened the session with a simple point:

- Science is mute. Data does not speak for itself.

- The brain’s job is to protect us from snakes, not to fairly evaluate your PDF.

- When people hear a new piece of information, they check it against a story they already believe.

If you do not intentionally shape that story, somebody else will:

- A talk radio host.

- A YouTube channel.

- A rumor mill in a small town.

The Forest Service values might be printed on posters, but they were getting out-competed by much louder narratives in the wild.

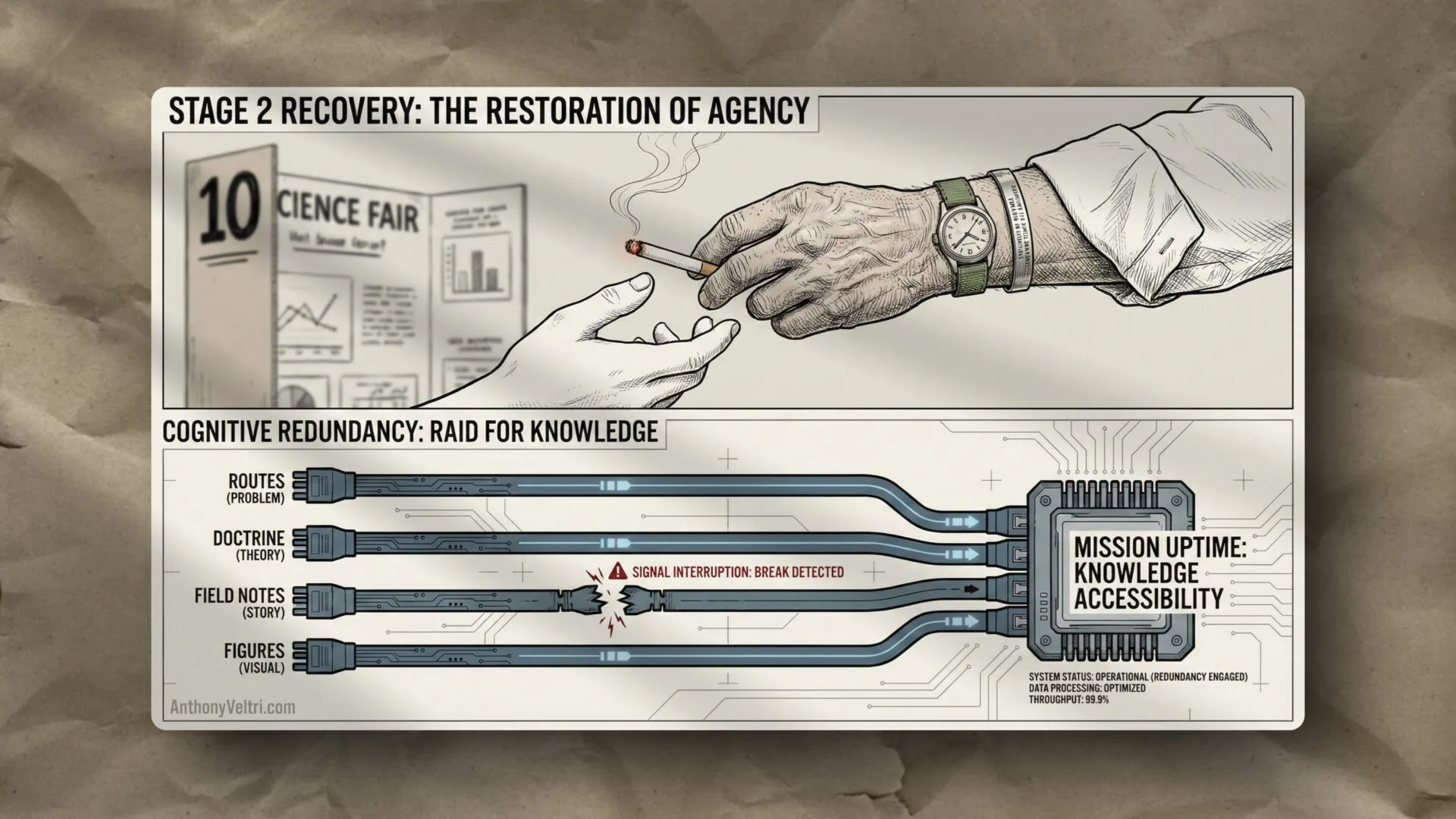

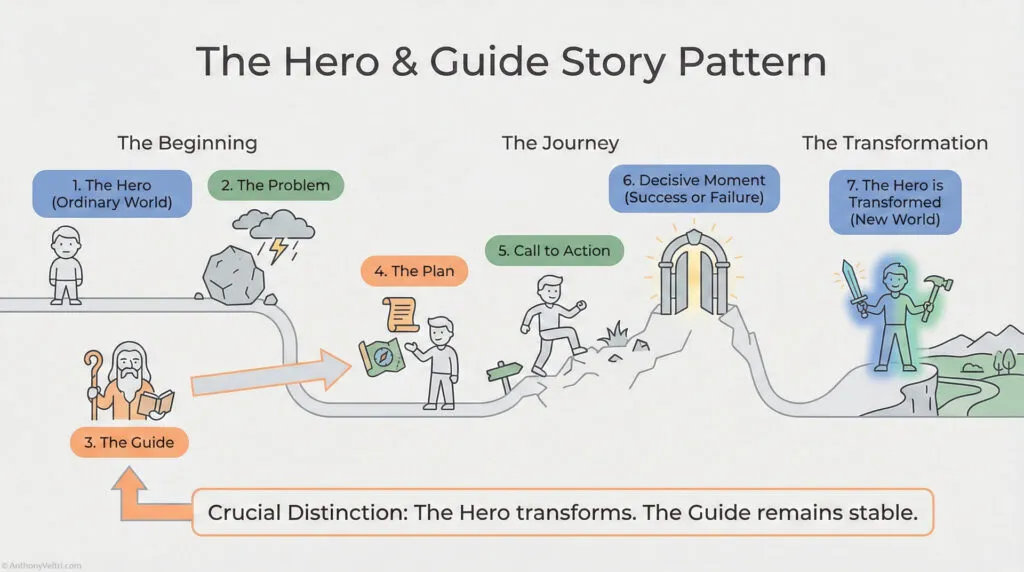

3. The Jedi Pattern: You Are the Guide, Not the Hero

Most organizations, especially public agencies, accidentally cast themselves as the hero in the story.

- “We saved the town.”

- “We did the burn.”

- “We delivered the program.”

In the workshop, I used Star Wars and a simplified Hero’s Journey to break that reflex.

- Luke represents the person in trouble: a community, a burned-out employee, a confused visitor, a line officer under pressure.

- Yoda / Obi-Wan represent the guide: someone who has seen this before and knows the terrain.

Then I gave them the punchline:

When your organization plays the hero, you are admitting you lack understanding, expertise, or a plan.

Heroes need guides. Guides already have clarity.

For Region 6, that meant:

- The towns and employees were the heroes, stuck in a frightening chapter of their story.

- The Forest Service’s job was to act like Yoda, not Luke: listen, name the reality, and provide a path forward.

This simple role shift opened the door for leaders to talk about grief, recovery, and resilience without sounding self-congratulatory.

4. A Simple Positioning Formula: W–V–X–Y–Z

Once people could see themselves as the guide, we needed a way to translate that into actual language.

I gave them a simple positioning pattern:

I help [W] achieve/avoid [V] so that [X], even if [Y], without [Z].

- W – Who you serve

- V – What they want to achieve or avoid

- X – Why it matters

- Y – The obstacle they are facing

- Z – The cost they want to avoid

A generic example:

“We help first-time campers feel confident and safe in our forests

so they actually enjoy their trip,

even if they have never been camping before,

without making them feel stupid for not knowing the rules.”

This is not about slogans. It is about clarity:

- Who are you the guide for?

- What are they actually trying to do?

- What is in their way right now?

- What pain are they trying to avoid?

For Region 6, we used this structure to rethink how they described resilience and care for:

- Fire-impacted communities.

- Employees dealing with chronic smoke, evacuations, and COVID deaths.

- Seasonal workers wondering if they should come back at all.

5. Designing the Region 6 Resilience Podcast.

Leadership wanted a podcast that would:

- Highlight resilience stories.

- Make staff feel seen and heard.

- Help communities understand what the Forest Service was trying to do.

The temptation was to brainstorm episodes based on internal interests. I took a different route:

- Pulled real search data around:

- “What can I do on public land?”

- “Is it safe to camp after a fire?”

- “Jobs with the Forest Service”

- “Hunting on national forest land”

- “COVID and wildfires”

- Translated those search phrases into episode concepts:

- “What can I actually do on public land near me?”

- “Is it safe to go back to the forest after a big fire?”

- “Why would I work for the Forest Service right now?”

- “What does resilience look like for this town, three years later?”

- Mapped each episode to the Hero’s Journey:

- Who is the “Luke” here?

- What are they afraid of?

- What does the Forest Service know that could help?

- What is the call to action?

The result was a podcast plan rooted in what people were already asking, in their own language, rather than what felt convenient to talk about from the inside.

6. The Values Trap: The Memory Test

This is the part of the workshop that landed the hardest.

Early in the session, I shared my own three values. For example:

- Integrity – Tell the truth, even when it is inconvenient.

- Utility – If it does not help someone, it is decoration.

- Courage – Be willing to say “no” to the wrong work.

We moved on.

Near the end of the workshop, I came back to this in a very low-stakes way:

“Out of curiosity, can anyone remember the three values I mentioned at the beginning?”

People called them out. Together, the room reconstructed all three. It was light, almost playful. Nobody was being graded.

Then I asked a second question, just as casually:

“Okay, one more: without looking anything up, how many of you can write down our official Forest Service values?”

I did not go person by person or make anyone sit in silence. It was clear, very quickly, that most people could not list them all. That was enough. I cut it off and made the point:

If a group can remember the guest speaker’s values from one slide, and not their own agency’s values that they have seen for years, you do not have embodied values. You have slogans.

Values that are not:

- Lived

- Repeated in plain language

- Connected to real decisions

…do not stick in memory. They sit on posters.

This is not a Forest Service problem. It is a systems problem.

7. Outcomes and What Changed

The Resilience initiative in Region 6 did not last forever. New administrations and shifting priorities eventually shut it down.

That does not mean the work was wasted.

In the time it existed:

- Staff had a shared language for talking about grief and resilience.

- The Jedi pattern gave leaders a safer way to frame their role as guides, not heroes.

- The Resilience logo and mugs acted as daily, tangible reminders that this was not “just another memo.”

- The podcast plan gave them a way to answer real questions instead of broadcasting generic messages.

Even after the initiative was nixed, the people who were in that room carried the pattern forward:

- Test whether your values are actually remembered.

- Stop trying to play the hero.

- Use real questions from your stakeholders as your content backlog.

8. How to Reuse This Pattern in Your Own Organization

If you lead a team, program, or agency and want to apply this, here is a simple sequence.

Step 1: Run a gentle recall experiment

If you want to test whether your values are actually living in people’s heads, do it in a way that is safe and low-stakes.

- First, give them something “forgettable.”

Early in a meeting, share your own three personal values or a simple three-item list that is not central to their jobs. Make it quick and human, not formal. - Later, come back to it.

Near the end, ask the room, casually:

“Does anyone remember the three values I shared at the beginning?”

Let people call them out together. No grades, no pressure.

- Then invite a private check on the organization’s values.

Say something like:

“Now, just for yourself, grab a piece of paper and try to write down our official values from memory. You won’t have to read them out loud.”

Give them a minute, then ask:

“How many of you feel like you got all of them? How many got one or two? How many drew a blank?”

- Call out the pattern, not the people.

The point is not to catch anyone out. It is to notice that a one-slide, one-time list from a visitor stuck better than the values that are supposedly central to the organization. That gap is where the real work starts.

You are not trying to run a boot-camp inspection or a board exam. You are giving people an experience of the difference between printed values and embodied, memorable values, and then offering to help close that gap.

Step 2: Recast yourself as the guide

Pick a specific audience:

- Fire-impacted communities

- First-time applicants

- New employees

- A partner agency

Ask:

- If they are the hero, what chapter of their story are they in right now?

- What are they afraid of or frustrated by?

- What do you know that could change their next step?

Write one paragraph that casts your org as the guide, not the savior.

Step 3: Use the W–V–X–Y–Z formula

Fill in the blanks:

We help [W] achieve/avoid [V] so that [X], even if [Y], without [Z].

Do a few versions. Make at least one of them so simple that a field employee or community member would nod along.

Step 4: Listen to real questions

Look at:

- Search queries hitting your site.

- Emails and voicemails from the public.

- Questions at town halls or meetings.

Turn these into episode titles, FAQ topics, or briefing themes.

If nobody is asking for your program in their language, you have a translation problem, not a marketing problem.

Step 5: Anchor the story in artifacts

Pick one or two small, durable artifacts:

- A logo and mug like Region 6 did.

- A recurring podcast segment.

- A short internal newsletter.

- A simple one-page briefing template.

The goal is not swag. The goal is to give people something to see and touch that matches the story you are telling about resilience, care, or mission.

9. Why This Matters Beyond Region 6

This case study is not about one region, one fire season, or one agency.

It is about a recurring pattern:

- Organizations declare values.

- The world hits them with overlapping crises.

- Staff and communities carry invisible scars.

- Leadership wants to signal that they care, but often reaches for memos and posters.

If people can remember a visiting speaker’s values from one slide,

and they cannot remember your own values from a decade of posters,

you do not need another slogan. You need a different story.

Your job, if you are serious about resilience, is to:

- Tell that story clearly.

- Live it in decisions.

- Repeat it in simple language.

- Give people artifacts and structures that make it hard to forget.

That is what we tried to do in Region 6.

You can use the same pattern where you work.

A Region 6 Forest Service Story About Narrative, Resilience, and Memory

Disclaimer:

This case study is based on volunteer work I did with a U.S. Forest Service region during the Chief’s Operation Care & Recovery effort. All interpretations, conclusions, and lessons here are my own and do not represent official policy or positions of the U.S. Forest Service or USDA.

1. Context: Why I Was in the Room

In 2020, Region 6 of the U.S. Forest Service was getting hammered from multiple directions:

- COVID was burning through staff, families, and communities.

- The Detroit, Oregon fires and surrounding complexes wiped out entire towns and landscapes.

- People were exhausted, angry, grieving, and still trying to do their jobs.

The Chief’s Operation Care & Recovery was launched nationally, but Region 6 was feeling the weight in a very specific way. Leadership wanted to talk about resilience, care, and recovery in a way that was real, not just a memo.

I was brought in as a volunteer to help:

- Shape the narrative around resilience.

- Design a podcast concept that would reach both employees and the public.

- Give leaders a way to talk about what had happened without sounding like a press release.

This guide is the pattern I used, and what I learned.

2. The Default Belief: “The Science Will Speak for Itself”

When I work with federal agencies, I hear some version of this belief a lot:

“We have science, we have values, we have a mission.

If people don’t understand us, that’s their problem.”

It sounds noble. It feels objective. It also fails.

So I opened the session with a simple point:

- Science is mute. Data does not speak for itself.

- The brain’s job is to protect us from snakes, not to fairly evaluate your PDF.

- When people hear a new piece of information, they check it against a story they already believe.

If you do not intentionally shape that story, somebody else will:

- A talk radio host.

- A YouTube channel.

- A rumor mill in a small town.

The Forest Service values might be printed on posters, but they were getting out-competed by much louder narratives in the wild.

3. The Jedi Pattern: You Are the Guide, Not the Hero

Most organizations, especially public agencies, accidentally cast themselves as the hero in the story.

- “We saved the town.”

- “We did the burn.”

- “We delivered the program.”

In the workshop, I used Star Wars and a simplified Hero’s Journey to break that reflex.

- Luke represents the person in trouble: a community, a burned-out employee, a confused visitor, a line officer under pressure.

- Yoda / Obi-Wan represent the guide: someone who has seen this before and knows the terrain.

Then I gave them the punchline:

When your organization plays the hero, you are admitting you lack understanding, expertise, or a plan.

Heroes need guides. Guides already have clarity.

For Region 6, that meant:

- The towns and employees were the heroes, stuck in a frightening chapter of their story.

- The Forest Service’s job was to act like Yoda, not Luke: listen, name the reality, and provide a path forward.

This simple role shift opened the door for leaders to talk about grief, recovery, and resilience without sounding self-congratulatory.

4. A Simple Positioning Formula: W–V–X–Y–Z

Once people could see themselves as the guide, we needed a way to translate that into actual language.

I gave them a simple positioning pattern:

I help [W] achieve/avoid [V] so that [X], even if [Y], without [Z].

- W – Who you serve

- V – What they want to achieve or avoid

- X – Why it matters

- Y – The obstacle they are facing

- Z – The cost they want to avoid

A generic example:

“We help first-time campers feel confident and safe in our forests

so they actually enjoy their trip,

even if they have never been camping before,

without making them feel stupid for not knowing the rules.”

This is not about slogans. It is about clarity:

- Who are you the guide for?

- What are they actually trying to do?

- What is in their way right now?

- What pain are they trying to avoid?

For Region 6, we used this structure to rethink how they described resilience and care for:

- Fire-impacted communities.

- Employees dealing with chronic smoke, evacuations, and COVID deaths.

- Seasonal workers wondering if they should come back at all.

5. Designing the Region 6 Resilience Podcast

Leadership wanted a podcast that would:

- Highlight resilience stories.

- Make staff feel seen and heard.

- Help communities understand what the Forest Service was trying to do.

The temptation was to brainstorm episodes based on internal interests. I took a different route:

- Pulled real search data around:

- “What can I do on public land?”

- “Is it safe to camp after a fire?”

- “Jobs with the Forest Service”

- “Hunting on national forest land”

- “COVID and wildfires”

- Translated those search phrases into episode concepts:

- “What can I actually do on public land near me?”

- “Is it safe to go back to the forest after a big fire?”

- “Why would I work for the Forest Service right now?”

- “What does resilience look like for this town, three years later?”

- Mapped each episode to the Hero’s Journey:

- Who is the “Luke” here?

- What are they afraid of?

- What does the Forest Service know that could help?

- What is the call to action?

The result was a podcast plan rooted in what people were already asking, in their own language, rather than what felt convenient to talk about from the inside.

6. The Values Trap: The Memory Test

This is the part of the workshop that landed the hardest.

Early in the session, I shared my own three values. For example:

- Integrity – Tell the truth, even when it is inconvenient.

- Utility – If it does not help someone, it is decoration.

- Courage – Be willing to say “no” to the wrong work.

We moved on.

Near the end of the workshop, I came back to this in a very low-stakes way:

“Out of curiosity, can anyone remember the three values I mentioned at the beginning?”

People called them out. Together, the room reconstructed all three. It was light, almost playful. Nobody was being graded.

Then I asked a second question, just as casually:

“Okay, one more: without looking anything up, how many of you can write down our official Forest Service values?”

I did not go person by person or make anyone sit in silence. It was clear, very quickly, that most people could not list them all. That was enough. I cut it off and made the point:

If a group can remember the guest speaker’s values from one slide, and not their own agency’s values that they have seen for years, you do not have embodied values. You have slogans.

Values that are not:

- Lived

- Repeated in plain language

- Connected to real decisions

…do not stick in memory. They sit on posters.

This is not a Forest Service problem. It is a systems problem.

7. Outcomes and What Changed

The Resilience initiative in Region 6 did not last forever. New administrations and shifting priorities eventually shut it down.

That does not mean the work was wasted.

In the time it existed:

- Staff had a shared language for talking about grief and resilience.

- The Jedi pattern gave leaders a safer way to frame their role as guides, not heroes.

- The Resilience logo and mugs acted as daily, tangible reminders that this was not “just another memo.”

- The podcast plan gave them a way to answer real questions instead of broadcasting generic messages.

Even after the initiative was nixed, the people who were in that room carried the pattern forward:

- Test whether your values are actually remembered.

- Stop trying to play the hero.

- Use real questions from your stakeholders as your content backlog.

8. How to Reuse This Pattern in Your Own Organization

If you lead a team, program, or agency and want to apply this, here is a simple sequence.

Step 1: Run a gentle recall experiment

If you want to test whether your values are actually living in people’s heads, do it in a way that is safe and low-stakes.

- First, give them something “forgettable.”

Early in a meeting, share your own three personal values or a simple three-item list that is not central to their jobs. Make it quick and human, not formal. - Later, come back to it.

Near the end, ask the room, casually:

“Does anyone remember the three values I shared at the beginning?”

Let people call them out together. No grades, no pressure.

- Then invite a private check on the organization’s values.

Say something like:

“Now, just for yourself, grab a piece of paper and try to write down our official values from memory. You won’t have to read them out loud.”

Give them a minute, then ask:

“How many of you feel like you got all of them? How many got one or two? How many drew a blank?”

- Call out the pattern, not the people.

The point is not to catch anyone out. It is to notice that a one-slide, one-time list from a visitor stuck better than the values that are supposedly central to the organization. That gap is where the real work starts.

You are not trying to run a boot-camp inspection or a board exam. You are giving people an experience of the difference between printed values and embodied, memorable values, and then offering to help close that gap.

Step 2: Recast yourself as the guide

Pick a specific audience:

- Fire-impacted communities

- First-time applicants

- New employees

- A partner agency

Ask:

- If they are the hero, what chapter of their story are they in right now?

- What are they afraid of or frustrated by?

- What do you know that could change their next step?

Write one paragraph that casts your org as the guide, not the savior.

Step 3: Use the W–V–X–Y–Z formula

Fill in the blanks:

We help [W] achieve/avoid [V] so that [X], even if [Y], without [Z].

Do a few versions. Make at least one of them so simple that a field employee or community member would nod along.

Step 4: Listen to real questions

Look at:

- Search queries hitting your site.

- Emails and voicemails from the public.

- Questions at town halls or meetings.

Turn these into episode titles, FAQ topics, or briefing themes.

If nobody is asking for your program in their language, you have a translation problem, not a marketing problem.

Step 5: Anchor the story in artifacts

Pick one or two small, durable artifacts:

- A logo and mug like Region 6 did.

- A recurring podcast segment.

- A short internal newsletter.

- A simple one-page briefing template.

The goal is not swag. The goal is to give people something to see and touch that matches the story you are telling about resilience, care, or mission.

9. Why This Matters Beyond Region 6

This case study is not about one region, one fire season, or one agency.

It is about a recurring pattern:

- Organizations declare values.

- The world hits them with overlapping crises.

- Staff and communities carry invisible scars.

- Leadership wants to signal that they care, but often reaches for memos and posters.

If people can remember a visiting speaker’s values from one slide,

and they cannot remember your own values from a decade of posters,

you do not need another slogan. You need a different story.

Your job, if you are serious about resilience, is to:

- Tell that story clearly.

- Live it in decisions.

- Repeat it in simple language.

- Give people artifacts and structures that make it hard to forget.

That is what we tried to do in Region 6.

You can use the same pattern where you work.

Last Updated on December 9, 2025